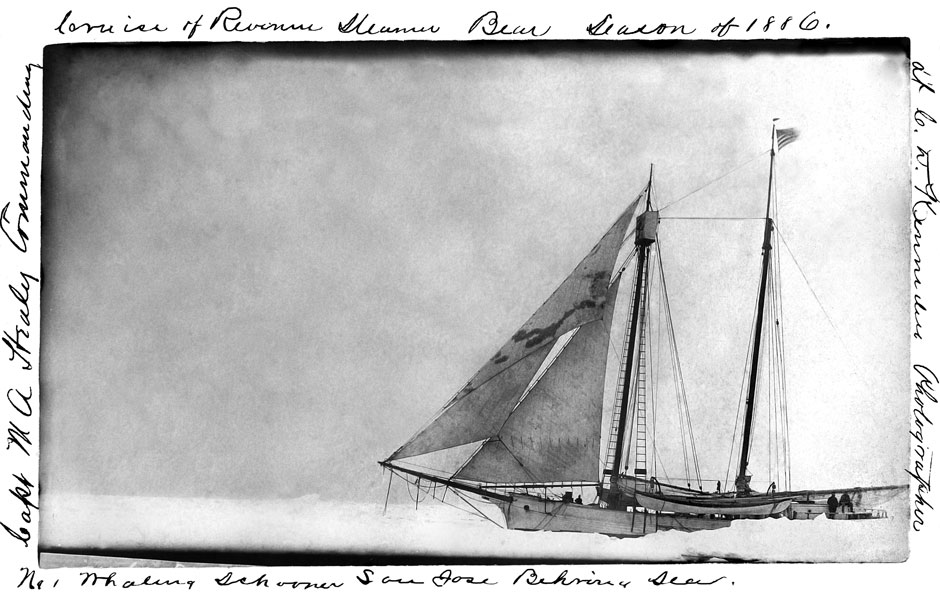

In 1886 Alaska had been American for less than two decades, Russian presence had waned, and the whaling industry widely occupied the region. The sole representative of American authority in those waters was the US Revenue Cutter Bear, a 198-foot, reinforced-hull vessel powered by both steam and sail. The ship’s mission was to confiscate illegal alcohol and guns, make observations for nautical charts, offer medical assistance to natives and ships’ crews, pick up explorers from an earlier US Navy expedition, and generally police the area. As a new book, Steaming to the North, shows, the Bear’s cruise that summer also produced some of the first photographs ever taken of that part of the world. Arranged into a narrative and explained with the help of the authors’ far-ranging research, the photographs—rediscovered in the 1970s under a porch in New Hampshire—chronicle the Bear’s journey from San Francisco to Alaska and Siberia, and give us a rare glimpse of a remote place and time.

Michael A. Healy, the Bear’s captain, had been born the son of a slave in Georgia. His slaveholder father brought Michael and his half-white siblings to New York to get a Catholic education; one of them went on to become the president of Georgetown University, another the bishop of Portland, Maine. Michael, the most footloose of this remarkable bunch, went to sea as a cabin boy in 1854, when he was fifteen. He received an officer’s commission at twenty-six, and had acquired the reputation as the most skilled sea captain in the western Arctic by the time he commanded the Bear. His crew consisted of eight officers and forty men. Third Lieutenant Charles D. Kennedy, a twenty-eight-year-old from New Bedford, Massachusetts, probably took all or most of the photographs.

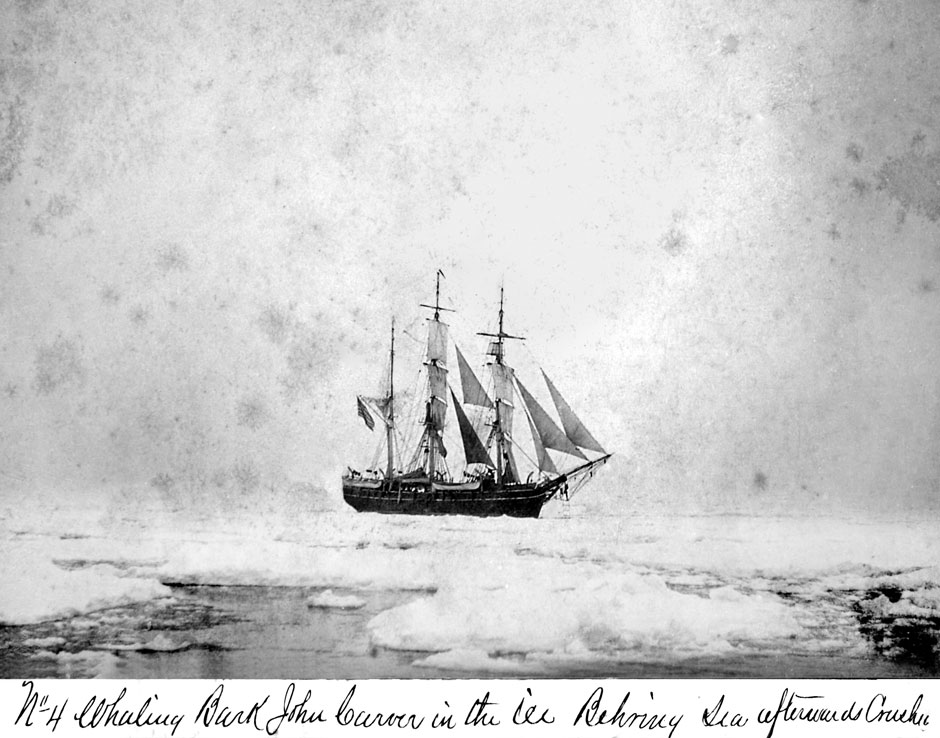

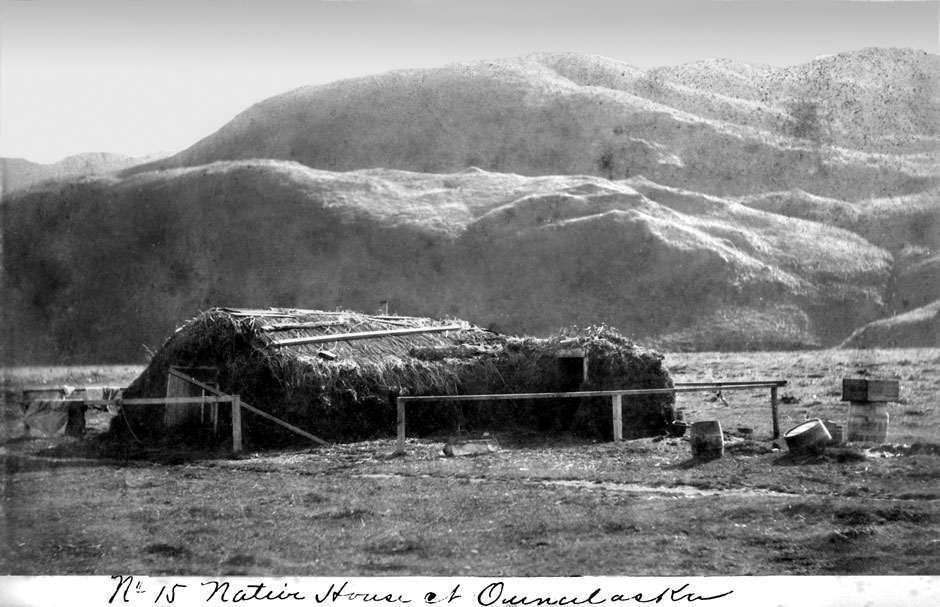

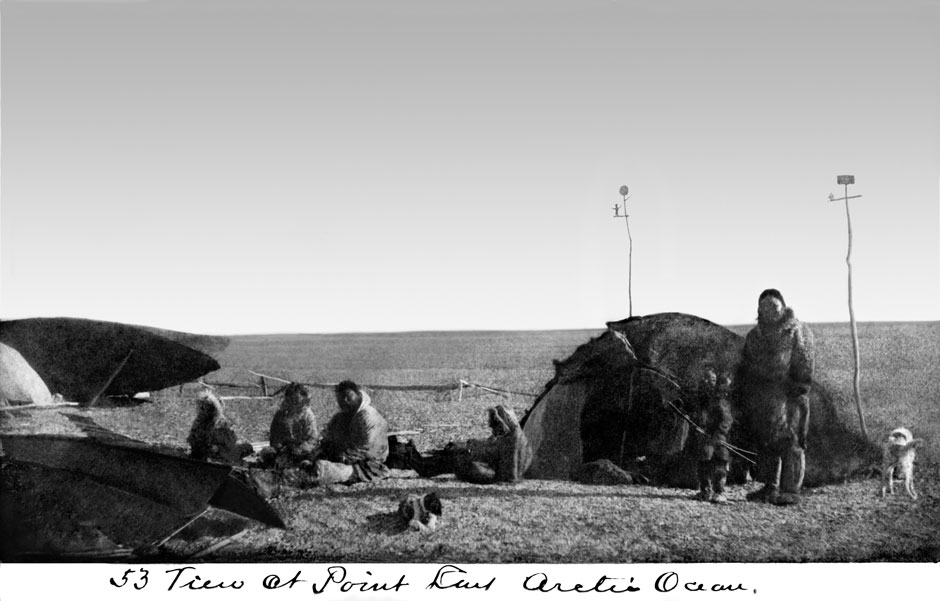

Many of the scenes—of whaling ships, villages, natives, sailors, landscapes and seascapes—possess the slightly abstract quality of staged photos done in a studio. No doubt this was a result of the near-constant, almost unearthly Arctic light in the months when the Bear sailed. The photos might lead us to believe that the sunlit season offers a mild interlude in the otherwise rough weather at these latitudes. In fact, most of the time the Bering Strait summer sky is like soggy blankets draped on your head, with visibility nil, pelting rain, and angry, storm-cloud-color seas. Kennedy must have waited patiently for the relatively clear weather evident in the photos.

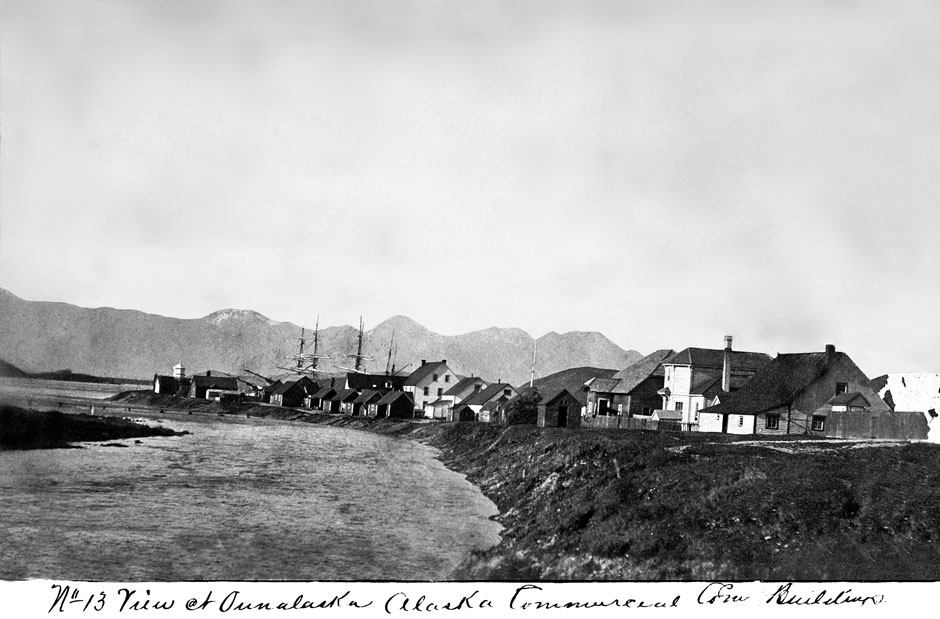

Even more striking today is the way the Bear pinballed between US territory and the Russian side, which Americans then referred to simply as Siberia. (It’s now more accurately known as Chukotka, or the Russian Chukotka Autonomous Okrug.) Most of her stops can be found on the Alaska state map in a Rand McNally Road Atlas. On May 5, 1886, the Bear set sail from San Francisco; on May 17 she reached Unalaska, in the Aleutian Islands. From June 8 to June 13 she was stuck in the ice off Russia, and on June 14 she continued to Mys Chaplino, or Chaplin Point, near the present-day village of Vendrekinot, in Chukotka. On June 18 she reached Cape Prince of Wales, at the Bering Strait’s narrowest point, where on good-visibility days you can see Asia and Alaska simultaneously. Later stops took her to Alaska’s North Slope in August, back to Chukotka in September, and eventually home to San Francisco in mid-October.

The book notes no contacts with Russian officialdom, and a lot of native traffic across the strait in both directions. This seems amazing now, after almost a hundred years of mutual Russo-American suspicion, including the complete lockdown of the Asian side under Soviet rule. On a visit to Nome not long after the end of the Soviet Union, I talked to an energetic Nome realtor who hoped to start a trans-strait ferry service that would carry freight, passengers, and ecotourists between the two countries. He also belonged to a commission to promote the construction of a tunnel from Alaska to Chukotka. Nothing came of these plans. The chronic cultural-bureaucratic intractability of the border continues to divide the rich natural environment that the Bear’s sailors experienced as a whole.

Advertisement

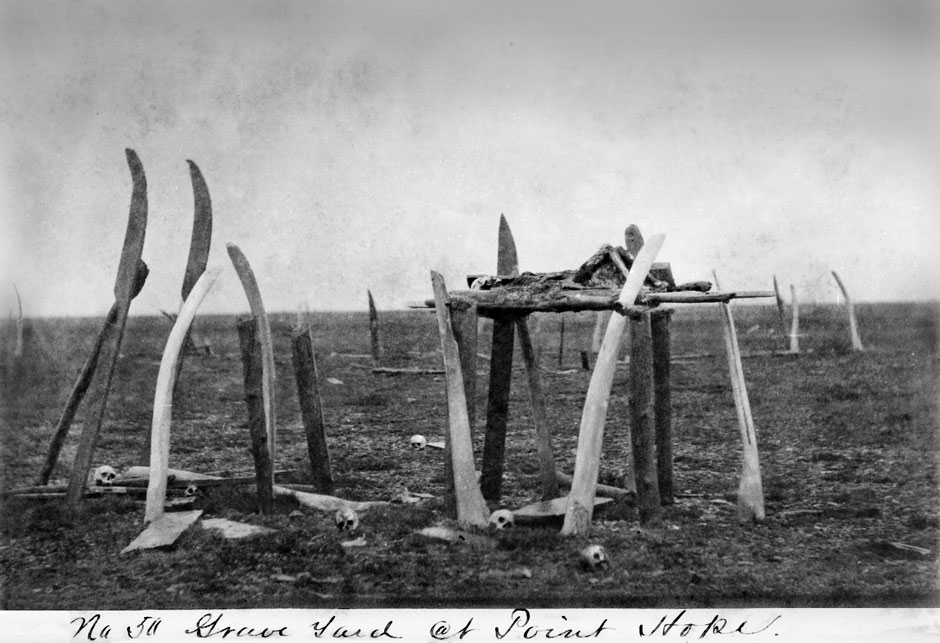

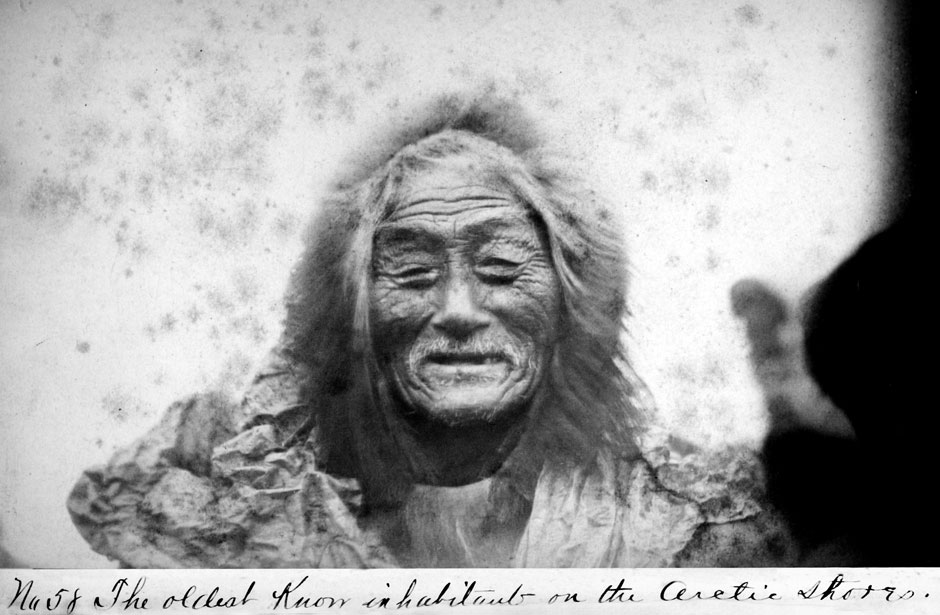

Ships encountered by the Bear, their later histories (the Bear herself survived many decades of service, finally sinking off Nantucket in 1963 while being towed), Arctic sites, native culture, and notable individuals of the region all receive the authors’ careful attention. At Point Hope, Alaska, a fierce local chief wore trousers made of mattress ticking and, when challenged to wrestle, leapt up in his subterranean dwelling and “kicked the gut window eight feet above the floor with both feet.” The book’s seventy-some pages of text are dense with similar hard-won facts and add an important chapter to the literature of Arctic travel. Given the epidemics that will come, photographs of natives take on a foreshadowing sadness, like last images of the condemned. Also painful is the larger portrait of this region as it waits to be even more despoiled. When the Bear’s crew saw it, one kind of oil was damaging it; the search for whale oil and baleen had driven the whalers to these waters after their prey had become scarce elsewhere. From today’s vantage we know that another kind of oil will hurt it more.

Arctic whaling spread disease and drunkenness among the native people and drastically drove down the numbers of whales. The rise of the petroleum economy probably saved the whales from extinction and temporarily reduced pressure on the natives. But when easy-to-drill oil became scarce, drilling rigs came to the same waters that the last whalers had sailed. Recent observers of the Arctic tell about sea-level rise washing away native villages, and melting permafrost, and the release of its previously trapped methane gas, and other developments associated with climate change. Our strange, hot future seems to be showing up earliest in Alaska. Steaming to the North provides another of the poignant rear-view-mirror visions of ourselves and our environment in which Americans specialize.

Steaming to the North is published by University of Alaska Press.