There are numerous uncertainties about what will happen on November 8 of 2016, nearly a year and a half from now, but one thing is not in doubt: it’s a very peculiar election, perhaps the most peculiar yet. It’s not just that there are, as of now, so many candidates. It’s also that some candidates were running before they announced—which is legally questionable—and at least one has announced twice (two, if one counts Bernie Sanders). It will also almost certainly be the most expensive election in history, with the wealthiest in the land able to have more influence than ever.

Hillary Clinton re-launched her campaign on Saturday, with far more noise than her initial entry into the race in mid-April because her first try, a taped “announcement” with supposedly “everyday people” of various colors and sexual leanings, followed by her “listening” to small clusters of Iowans, some of whom were her own campaign people, didn’t go over so well. And so this time she took quite a different tack by re-announcing on Roosevelt Island to a fairly large crowd packed into a fairly small space (to make the crowd look larger) and waving little American flags, the scene framed by a row of larger flags. Her speech was heavy on domestic proposals, most of them crowd-pleasers, though she projected little passion. She got the requisite cheers but no discernible frenzy. (Her advisers are reported to be worried about this aspect of her campaigning.) Of course, as many have pointed out, her long list of proposals was unrealistic, but most campaign speeches are. The speech was delivered in pretty much a monotone; unlike her husband, she isn’t a natural at politics. The humor seemed forced; neither Clinton is known for wit.

In her relaunch speech, Clinton was noticeably vague about foreign policy—she summed up the international situation thusly: “There are a lot of trouble spots in the world, but there’s a lot of good news out there too.” As one of her credentials she pointed out that she had sat in the Situation Room when US forces took out Osama bin Laden. (Naturally, she didn’t mention her vote for the Iraq War, which by 2008 she was saying was a mistake.) But the hawkishness she’s displayed since entering the Senate in 2001 worries many Democrats who otherwise favor her.

In her memoir, Hard Choices, Clinton made a point of saying that she differed with the president in early on favoring the arming of the so-called “moderate” Syrian rebels (though little was known about who they actually are) and, predictably, after Obama later decided to do so, some of the munitions reportedly fell into the hands of the pro-Assad Syrian army and likely also of ISIS. Clinton’s campaign officials have been reported as believing that in 2008 she didn’t adequately stress that she would be the first woman president, though I don’t think that that was lost on anyone. If she plays up the grandmother thing too much that could also backfire; the country isn’t looking to be mothered but to be led.

It should come as no surprise that Bernie Sanders has attracted large crowds and scored well against Clinton in some early polls. A Wisconsin straw poll in early June had Sanders only eight points behind Clinton in that state. Excitable election observers now say that Sanders is gaining on Clinton in Iowa and New Hampshire. Sanders’s persona has made him seem the truth-telling candidate, unbound by conventionality—someone who attracts people because they cotton to his positions (however unrealistic, as in the case of free college tuition for all) and straight talk. Sanders could be this election’s Ross Perot, or Ralph Nader—particularly if he were to take his success (if it lasts) seriously enough to launch a third-party candidacy; in any event he is likely to be a thorn in Clinton’s side.

Though Sanders can be snappish, his appeal was predictable because he comes across as authentic—and Clinton doesn’t. She tends to come across as a package of positions fashioned by her and her campaign advisors to meet the perceived mood of the moment. At this point she’s a populist in the mode of Elizabeth Warren, whose continuous attacks on Wall Street have gained her a devoted following on the Democratic left. (Wisely, Warren has resisted calls to enter the race. She’s not equipped to deal with foreign policy and if she were to run and lose she would also lose much of her influence.) And like just about all the candidates, including Republicans, Clinton emphasized that she’s “fighting for the middle class.” Her campaign made it clear to reporters that Clinton is striving to be portrayed as “a fighter.”

Advertisement

Clinton’s great challenge—this assumes, perhaps prematurely, that she won’t face serious opposition for the nomination—is to attract enough Democrats who are sufficiently excited about her to vote on election day. Most of us know Democrats who supported her in 2008 but now do so reluctantly, if at all. (A group of Wellesley graduates who canvassed for her in 2008 aren’t willing to do so this time.) The chief problem appears to be disappointment—for among other things her refusal to take strong positions on some highly controversial issues. Take the trade bill. She was anxious not to alienate the left, who opposed it, yet reluctant to move too far from her earlier position, as Secretary of State, championing it. Also, to come out against it would be another blow to Obama. Finally, in Iowa on Sunday, the day after her re-launch, she more or less sided with Democrats who had in effect voted down the president’s authority to negotiate a trade deal that Congress would only be allowed to approve or disapprove.

Also, to many people who would greatly prefer Clinton to a Republican, the controversy about her emails and her use of a private server brought back memories of the missing billing records of her Little Rock law firm and other events in the Bill Clinton White House, in which her antipathy toward the press and right-wing opponents led her to make mistakes. When the email story broke, some Washington commentators predicted that it was too esoteric to matter to the folks “out there,” but the public caught on quickly that something was wrong: yet another Hillary crisis. A lot of Democrats don’t want to take that ride again. If too many Democrats decide it isn’t worth bothering to vote for Clinton—if even the prospect of a Republican president doesn’t adequately dismay them—it could prove a big problem for her in November 2016.

Pollsters try to take intensity of support into account, but they’re not always successful. It’s worth remembering that the polls were wrong in the last two federal elections, in 2012 and to a greater extent in 2014. Not only is intensity unpredictable; there may be major events that affect the election climate—even days before the voting, as happened in 1980—and much also depends on the strength or weakness of the opposing candidate. Unless the candidates are far apart in voter support the final result of most races is impossible to predict. (I gave a talk in late October, 2000, that I divided into two parts: why Bush would win and why Gore would win. I was right on both counts, but that’s another matter.)

The Republicans, meanwhile, are in a sorry mess. This election is so unusual that, according to those who study the fever charts, we’ve already had a “front runner” come and go. It was widely thought that as soon as Jeb Bush hinted he might run he was the obvious nominee; it was over. His early indication of a possible candidacy, as far back as last December, did achieve its apparent purposes of letting the big Republican donors know that he’d be available and of discouraging Mitt Romney from running again; but it wasn’t successful in persuading Marco Rubio, previously a Bush protégé, to stay out of the race.

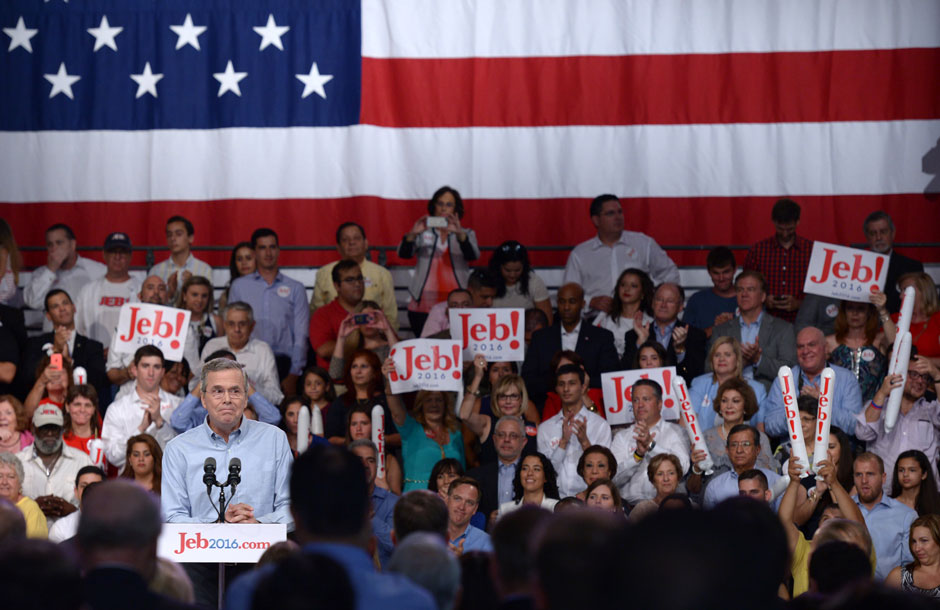

Jeb Bush may turn out to be the embodiment of the phenomenon that a candidate can look good on paper but doesn’t run on paper. Bush had been running what seemed a joyless campaign, as if he were going through the motions out of a sense of duty—it was almost painful to behold his twisting and turning until he figured out how to answer the inevitable question of whether he would have gone into Iraq knowing then what we do today. (He ultimately got to “No,” but the basis of the question—given what we know now—offers a cop out, since twenty-two Democratic Senators, including Bob Graham, another Floridian, who was chairman of the Intelligence Committee, voted against going to war to depose Saddam Hussein at the time.) Bush perked up in his announcement speech, thus calming the nerves of those Republican donors and operatives and gurus who had thrown their support to him in the theory that he was a shoe-in for the nomination. But it’s not yet clear who his constituency is.

Bush is often described as moderate but that seems more a reflection of his easy-going style than his record as Florida governor, which was quite conservative. His prominent involvement in the highly emotional Terri Schiavo case, strongly opposing her being released from her vegetative state, might still appeal to Christian conservatives. But the Christian conservatives’ current litmus tests seem to be whether a candidate would attend a gay wedding, or is urging that states not comply with their own laws prohibiting discrimination against same-sex couples.

Advertisement

The parties now have no gatekeepers, and Republican chairman Reince Priebus is powerless to prevent even the most preposterous candidates from entering the race. Unlike the case of his older brother, around whom other governors and party leaders coalesced after he won his second term as governor of Texas, Jeb Bush will have to fight it out with whoever decides to run this time. We often muse about why this or that politician entered the contest but the most useful answer is, Why not? An unsuccessful, even ridiculous campaign can be lucrative. Book contracts become more remunerative. Speaking fees go up. New opportunities open up. After he dropped out of the 2012 race the briefly famous Herman Cain got a talk radio show in Atlanta. In addition, through his extensive email list he promoted miracle drugs, including one purported to cure erectile dysfunction. Mike Huckabee got a television program on Fox after his 2008 run, and is now trying to reestablish his position as the prime candidate of the Christian Right, though this time he’ll be directly challenged by Rick Santorum, who is trying to reenact his own successful run in Iowa in 2012 (so far, that’s not happening). Newt Gingrich parlayed his 2012 run into a short-lived revival of “Crossfire” on CNN and is still a presence as a television commentator.

At this point, while the numerous Republican candidates are getting their campaigns and positions in order, a lot of the focus is on making sure that they can appear in the first set of debates, while some have yet to announce. A preliminary decision by Fox to feature only the top ten candidates in the polls for the first debate, which it’s hosting in August, inevitably proved unsustainable. The early polls among the candidates are meaningless; moreover, a potentially strong candidate such as John Kasich, who has yet to enter but is expected to do so shortly, is for the moment polling so low, in the single digits, that he wouldn’t have made the cut. Fox is now revising its plan.

But any effort to give all candidates some sort of debate exposure raises problems: how many can appear onstage at the same time and still provide a real basis for voters to make a decision? Whatever form this election’s early Republican group-appearances take, they will more than ever put the emphasis on the catchy one-liner. (This is one of the reasons Obama hated the debates.) The press covering these events can be counted on to go along with that, even perpetrate it. The “debates” will have the aura of a twitter contest.

Whether in a debate or another kind of appearance, a candidate’s blooper, gets far more attention than it deserves: George Romney saying that he’d been “brainwashed” by the generals in Vietnam (so did some presidents); Edmund Muskie “crying” in the snow (it wasn’t even clear that he was crying); and most recently, Rick Perry’s inability to remember the third agency he wanted to eliminate (people on television are often warned not to say that they have three points to make as they’re likely to forget the third). I even thought that Perry’s “oops” was said with a bit of charm, but currently the press is beating him over the head with it as if it’s the only thing he said in his abortive 2012 campaign.

The large number of Republican candidates may also have the consequence that one could succeed in a primary or caucus simply because of a splitting of the vote among others who are like-minded. Unless a significant number of Republicans are driven from the race early—less likely for those that have their own billionaire to back them come-what-may—the candidates who fight it out to the end, and even the nominee, could be more the product of math than of genuine sentiment within the party.

There’s still a lot to learn about each candidate: the “even-handed” profiles, with newspapers reaching for “balance,” can be misleading. We got our most disastrous president as a result of some pundits declaring in 1968 that there was a “new Nixon.” As for the process itself, the way John Kennedy was chosen as the Democrats’ nominee in 1960 probably made the most sense. The candidates had to enter a few primaries to show their mettle and let others see how the voters responded to them. Then the party bosses—governors of key states and assorted poobahs—would decide on who the nominee should be, usually on the basis of who would be the most electable, a decision to be ratified by the party’s convention.

But that method was gone and done as of the violent 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago, which was followed by “reforms” that gave the primary and caucus voters ultimate say on who would be the nominee. Journalists who continued to lather at the thought of a “brokered convention” were doomed to disappointment. With as much at stake as there is—from the Supreme Court to the Middle East to a newly aggressive Russia—the rest of us can only hope that they choose wisely.