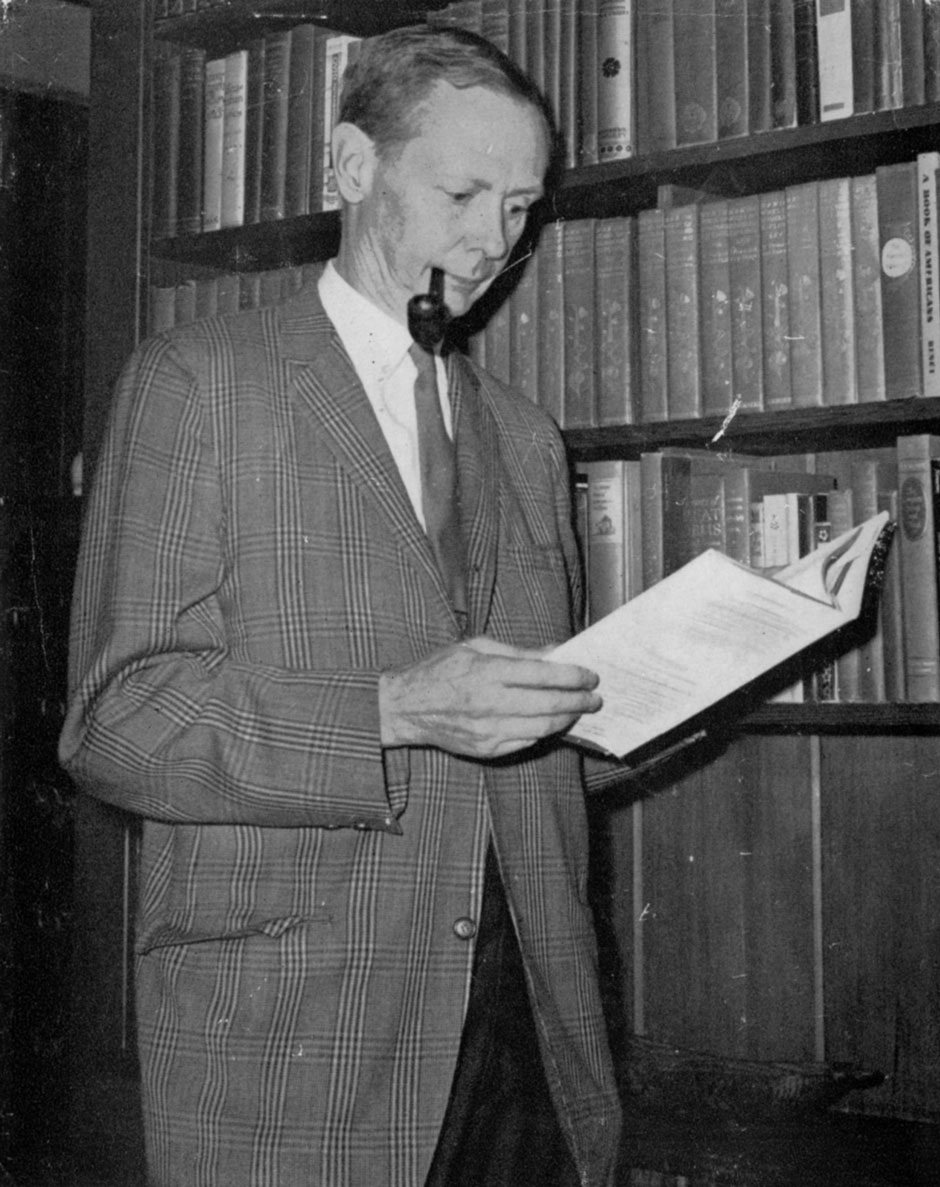

The author photograph of William Sloane on the back of the 1964 edition of The Rim of Morning shows a hawk-eyed gentleman with a pipe clamped in the corner of his mouth and an open book in his hands. He’s in a library (perhaps his own); many more books line the shelves behind him. This seems fitting, because books were Sloane’s life. He graduated from Princeton (class of 1929), worked for a number of publishing houses, directed the Council on Books during World War II (where books were pronounced “weapons in the war of ideas,” which sounds suspiciously like propaganda to me), and went on to serve as managing director of the Rutgers University Press. He also formed his own well-respected publishing company, William Sloane Associates, and served on the faculty of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in Vermont. A busy and productive life of books and reading, you would say.

Yet there was more to Sloane’s love of books than editing and publishing. In the 1930s, he also wrote two remarkable novels, To Walk the Night (1937) and The Edge of Running Water (1939), composing mostly on weekends and in the evenings. (Sloane’s only other published work—so far as I can determine—was a short story called “Let Nothing You Dismay,” which can be found in an anthology titled Stories for Tomorrow, which he edited.)

It’s interesting to note that in 1937 he met Carl Jung and was amazed to discover that the great psychotherapist had read To Walk the Night (in its earlier form, as a play), and felt that the book’s central conceit, of a “traveling mind,” fit perfectly with his, Jung’s, idea of the anima as a free-floating and quasi-supernatural archetype of the unconscious mind. At that same memorable luncheon, Sloane met another idol whose ideas are reflected in his novels: J.B. Rhine, inventor of the famous Rhine ESP cards and pioneer (at Duke University) in the study of extrasensory perception.

Although Sloane was clearly a science-fiction fan and conversant with the field—he edited the anthologies Stories for Tomorrow and Space, Space, Space—neither of his novels are, strictly speaking, science fiction. They are good stories, and can be read simply for pleasure, but what makes them fascinating and takes them to a higher level is their complete (and rather blithe) disregard of genre boundaries.

Both books certainly contain elements of science fiction. In The Edge of Running Water, Julian Blair is trying to get in touch with his dead wife via an electricity-powered machine he has created for just that purpose (although he has a spiritualist medium waiting in the wings, just in case). In To Walk the Night, Professor LeNormand and his student, poor damned Jerry Lister, are working on something called “A Fundamental Critique of the Einstein Space-Time Continuum,” a study that leads to their deaths.

Both books contain elements of mystery. Much of Edge is concerned with just how Mrs. Marcy, the unlucky housekeeper, met her death…and, of course, whodunit. Much of To Walk is a kind of “locked observatory” mystery: what caused LeNormand to burn to death…and, of course, whodunit. We understand that neither mystery will have a strictly rational explanation, which adds a resonance to these stories that no Agatha Christie novel can match. To Walk the Night owes much more to Charles Fort (The Book of the Damned, Wild Talents, Lo!) than it does to the mystery or horror writers of the time.

Both books also contain elements of horror. Boy, do they. No one can read The Edge of Running Water, the more successful of the two, without a frisson of fear when that awful blankness appears in Blair’s workshop—a blankness that threatens to suck in not just papers and furniture but perhaps the whole world. And no one can read the story of Luella Jamison’s disappearance in To Walk the Night without a similar shiver.

Because they ignore genre conventions, Sloane’s novels are actual works of literature. Perhaps not great literature; no argument will be made here on that score. If one wants great American literature from the Thirties, one must go to Hemingway, Faulkner, and Steinbeck. But if one compares these novels to what was then being published in science-fiction magazines like Thrilling Wonder Stories, or so-called “shudder pulps” such as Weird Tales, what a difference in language, diction, theme, and ambition!

Sloane builds his stories in carefully wrought paragraphs, each one clear and direct. Here is a man of the old school, who learned actual grammar in grammar school (complete with the diagramming of sentences, one suspects), and probably Latin at the high school and college levels. One chapter of To Walk the Night is titled “Cras Amet Qui Numquam Amavit,” which means—loosely translated—“Let him love tomorrow who has never loved, and let him who has loved, love tomorrow.” It’s interesting to me that the English translation is eleven words longer than the Latin, speaking to that language’s admirable brevity. It’s been my experience that even bad storytellers with a solid grounding in Latin are unable to write bad prose, and Sloane had serious narrative chops to go along with his basic writing skills. The very first sentence of Edge—“The man for whom this story is told may or may not be alive”—is as good an opener as I’ve ever read in my life.

Advertisement

The curtain-raiser of To Walk the Night is more businesslike and less enticing, but the writing nonetheless sparkles with witty grace notes: “She led the talk around to the question of the winter styles with all the finesse of a children’s photographer arranging a difficult grouping.” That’s a linkage Raymond Chandler might have made, although Chandler’s version would probably have been a bit punchier. Sloane is also allusive in a pleasantly scholarly way that few pulp writers of the day could have matched. In To Walk, he writes, “Maybe the Italians can live happily on the slopes of Vesuvius, but I am not that sort of person.” It’s a nifty insight into the narrator’s character, but one has to know what Vesuvius is (and what happened there) to really appreciate it.

Despite the trappings of science fiction (a mere flick of the authorial hand, really), and some of the conventions of the mystery novel (much interrogation of witnesses, and in Edge, a fair amount of hugger-mugger about footprints in the mud), I would argue that these are essentially horror novels. In The Edge of Running Water, Sloane’s subject is nothing less than what may exist after death, an idea I have approached myself in three novels, and never without a sense of awe at the tremendous implications of the subject. In To Walk the Night, we discover that a disembodied brain—perhaps an alien from space, perhaps a human intelligence from another time-stream or dimension—has inhabited the body of an “idiot” girl named Luella Jamison, transforming her vacuity into coldly classical beauty.

In the hands of his horror contemporaries—H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, August Derleth—such frightening concepts would have been rendered in thundering, florid prose, complete with words like cyclopean and phrases like the hoary primordial grove. I’m not knocking Lovecraft—there are plenty of reasons why his contemporaries imitated him—but Sloane is more reasonable in his approach, more rational, and this makes his work both accessible and ultimately more disturbing. Also, Sloane could write snappy dialogue, a talent very few contemporaneous horror writers seemed to possess. “Good God, Julian,” Edge narrator Richard Sayles exclaims to his old friend at one point, “when you duplicate a séance, you duplicate it. This looks like a Black Mass in a futurist play.”

One can’t imagine Lovecraft ever writing such a line, especially during our first entry into Julian’s laboratory, a locked room that drives our curiosity for the first three-quarters of the book. Lovecraft never would have considered highlighting horror with humor. For one thing, it didn’t fit his classical concept of the genre; for another, he (like many horror writers then and now) seems to have had no sense of humor. Here, though, it works, and works brilliantly. Sloane’s writing is drum-tight, but his approach is looser; he pulls the reader in and then begins turning up the heat. He understood that before a pot can boil, it must simmer.

My only regret is that William Sloane did not continue. Had he done so, he might have become a master of the genre, or created an entirely new one. Yet we must be grateful for what we have, which is a splendid rediscovery. These two novels are best read after dark, I think, possibly on an autumn night with a strong wind blowing the leaves around outside. They will keep you up, perhaps even until the rim of morning.

Adapted from Stephen King’s introduction to William Sloane’s The Rim of Morning, to be published by NYRB Classics on October 6. Illustration by Edward Gorey.