I had lazily pigeonholed E.H. Shepard as the genius who drew Winnie-the-Pooh, Eeyore, Tigger, Kanga, and Roo, his images as enduring as A.A. Milne’s text, and who also gave us the unforgettable Ratty and Mole and Toad in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows. Here he draws with deft pencil strokes and minimal background, and a cartoonist’s eye for short-hand shape; silhouettes of these figures would be instantly recognizable. But the genius lies in his evocation of movement: Pooh’s rotund clumsiness, Eeyore’s saggy body and roping head, Tigger’s unstoppable bounce, Kanga’s panic as baby Roo disappears. This is the Shepard we know best.

Yet in an intriguing exhibition at the House of Illustration, the brilliant new public gallery behind King’s Cross station in London—the first place in England to give real space to this underrated art—Shepard’s work does not show Pooh’s Hundred Acre Wood, or Ratty’s slow-flowing Thames. Instead he is sketching amid the mud and gunfire of the World War I trenches—“that dreadful countryside,” as Shepard called it, made vividly immediate in his depiction of shells exploding like puffs of cotton wool against grey mist and broken trees.

But how do these worlds fit together, that of the tender illustrator of children’s books, and the officer with his sketchbook in the trenches?

Ernest Howard Shepard was already drawing with passion as a child, fascinated by two subjects, soldiers and the theater—both of which would mingle, oddly, in his wartime work. Born in 1879, he grew up in a privileged, artistic London household: his father was an architect and his mother Jessie, who died when he was ten, was the daughter of a well known watercolorist, William Lee. At sixteen, when Shepard was studying at Heatherley’s Art School—and gained the lifetime nickname “Kipper”—he won a five-year studentship at the Royal Academy School. Here he met his wife, another talented artist, Florence Chaplin, who turns up in this exhibition in smiling student photos and in a trio of comic sketches from their tender, almost daily, wartime letters, modeling her new underwear, a teasing, sexy reminder of life away from bullets and shells.

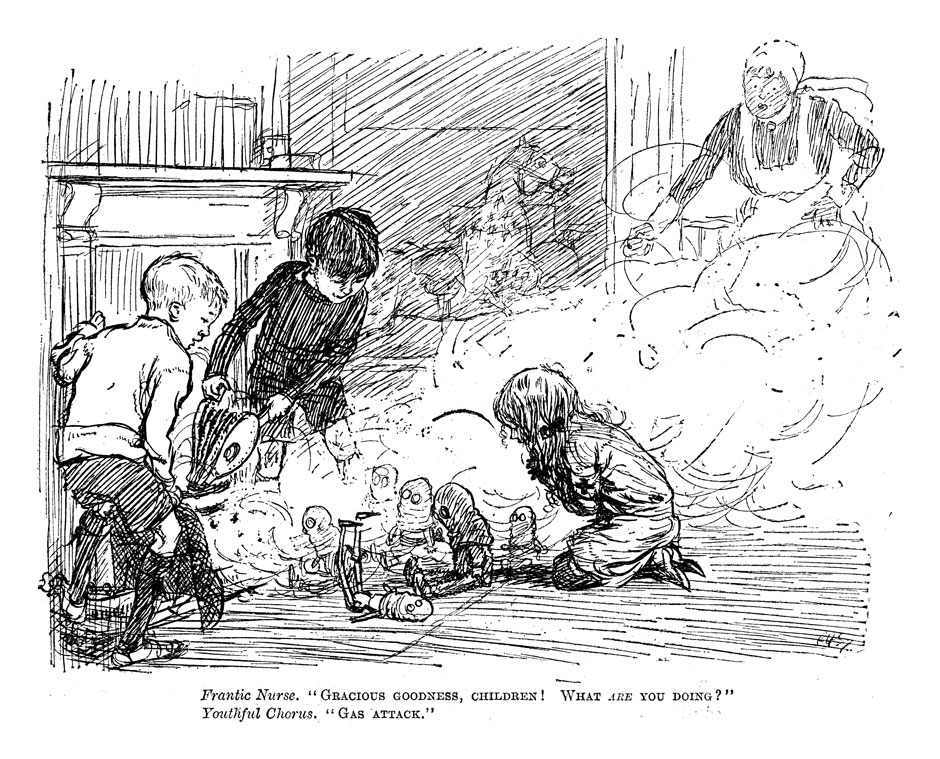

Illustration, like teaching, is often a way for art students to add to their income, and even while he scooped up RA scholarships and prizes, Shepard was sending work to magazines. He drew sweet, conventional scenes for classics like Tom Brown’s School Days, and one of the most disconcerting moments here is when these fresh-faced, well-brushed children turn up in a cartoon, enthusiastically sweeping ash out of the fireplace onto a bunch of toys, which are all wearing gas-masks, shrieking “Gas attack! Gas attack!” He understood the violence as well as charm of a child’s imagination, and the distorted impact of war.

Most of all in his prewar days, Shepard longed to join the elite group of cartoonists in Punch, of which Florence’s grandfather had been one of the founders. He had just managed this, with graphic social cartoons, when war broke out. In 1915 he joined up, soon to serve as an artillery officer with the 105th Siege Battery of the Royal Garrison Artillery. He was there with his troops on the Somme, at the battles of Arras and at Passchendaele, and later, in the last days of the war, in the fierce, snowbound fighting in the Italian Alps. Everywhere, he took his sketchbook.

Shepard made topographical drawings for army intelligence, sent work home to family and friends, and continued to draw his cartoons, mostly for Punch. At the outbreak of war, Owen Seaman, the magazine’s editor, had been convinced that Punch would go under, as this was no time for jokes. On the contrary, friends told him, “your work is just starting,” and humor would be needed more than ever. This proved true, not least because the secret War Propaganda Bureau enrolled him in the task of raising morale by showing the indomitable spirit of the British people and forces. But when Seaman asked for cartoons on subjects other than the war, Shepard replied that “it was almost impossible to think of anything else.” In the spring of 1917, at Arras, Shepard took over from his commanding officer and was awarded the Military Cross, its citation reading, “His courage and coolness were conspicuous.”

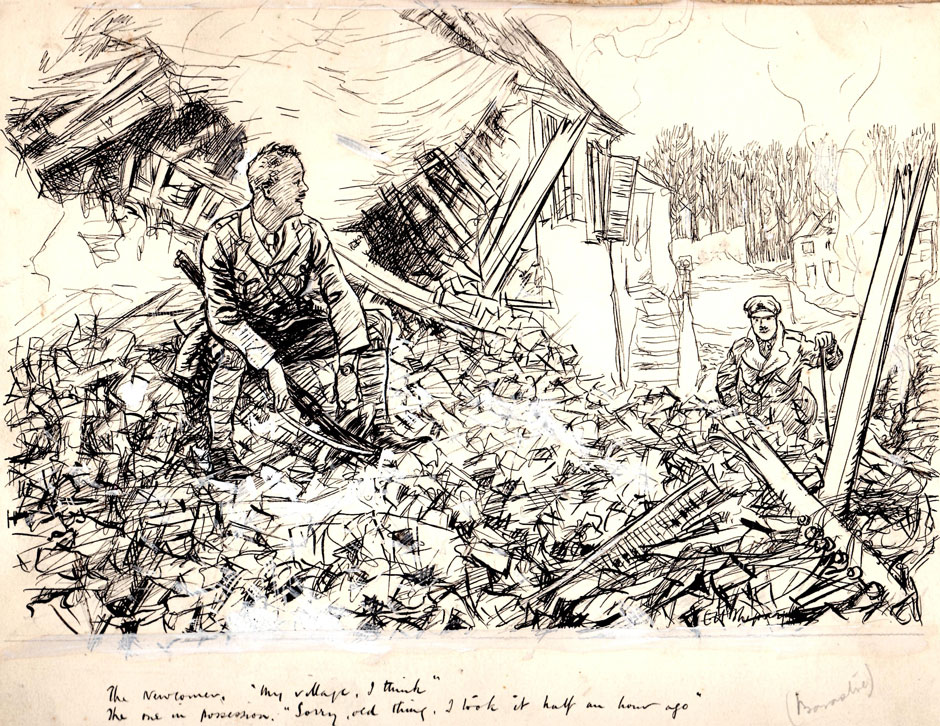

For months, his life, like all those on the front, was surrounded by slaughter. His sketchbook was full of pictures of crammed dugouts and rough shelters. He drew the chaotic rubble of no-man’s land, the plight of the wounded, and the tall roadside crucifix used as a lookout post by the Germans. At Passchendaele, in September 1917, in rapid, urgent sketches, he showed his own gunners ramming in shells—one of these great howitzers would explode a few weeks later, killing four men. In these sketches, not intended for publication, he simply drew what he saw, his pencil lines quicker, more delicate than his prewar work, his art extending and expanding in sensibility.

One great heartbreak was the death of his elder brother, to whom he was very close: on his map of Albert, a vital point in the battle of the Somme, he marked the coordinates of his brother’s grave. Nothing of the horror appeared in his letters home, although after Passchendaele, when his promised leave was cancelled and he was sent to the Italian Front in November 1917, he said he could “cry and cry.” Outwardly, however, Shepard was a cheery soul. In 1917 he told Seaman he was too busy for Punch work, but the cartoons that he did send showed he could find humor anywhere. Much of this is of the “stiff upper lip” kind, employing clichés of fat, thuggish Huns (he isn’t very good at drawing villains) and of toffish British officers and yokel-type Tommies. In a typical example, a staff officer points to a ribbon pinned on as a soldier’s battle honors:

Staff Officer (inspecting scratch collection G.S. Men). ‘Ah, my man—ribbon eh?

Don’t seem to remember the colours. What campaign is that?’

G.S. Man (proudly). ‘First prize, ploughin’ match at Yeovil, Zur’.

It’s uncomfortable to smile at the class-based jokes, typical of the period. But one can see how much Shepard’s men would have liked his high spirits: they thought him lucky, clustering round him, sure he would never be hit. In Italy, where his unit fought in the deep snow of the Asiago plateau, the gunners were aided, as they had always been, by his drawings of enemy positions. When an armistice was signed, Shepard stayed on until 1919 to cope with captured artillery. We can feel his exhaustion and his compassion in sketches of captured troops and of refugees on the road.

But there’s still plenty of humor in Venti Quatro, the soldiers’ magazine he edited, satirizing the gung-ho coverage of the British press, so far from the bitter reality. His wit is not verbal, but visual—a quality hard to define—seen here in affectionate caricatures of fellow officers and in the wonderful, rhythmic dance of beak-nosed, moustachioed officers in swirling tutus in Close of the Italian Season. Grand “Peace Ballet” finale.

He was still relatively unknown, but back home, as part of the editorial board at the famous “Punch table,” he sat next to the publisher E.V. Lucas, who persuaded A. A. Milne to use him to draw the pictures for When We Were Very Young. The three Pooh books followed, from 1926 to 1928, and, among other commissions, The Wind in the Willows in 1931. He continued to work for Punch until the 1950s, drawing cartoons—this time from the Home Front—during World War II, and kept up his work as a book illustrator until his last years, although rather regretting that popular interest in Pooh, “that silly old bear,” swamped recognition of his other work. He died in 1976, aged at ninety-six.

Shepard’s peacetime drawings, with their pure mastery of line, have a distinctive sweetness—not a rigorous art-critical term, but true. And in the drawings of animate toys and talkative animals, there is a shrewd observation of quirky human nature that bears witness to Shepard’s own endearing character, and to the deep understanding that he gained by sketching the terror and the comradeship of war.

“E.H. Shepard: An Illustrator’s War” is on view at the House of Illustration in London through January 24, 2016