… and then return, some day,

Through the torn orange veils of an early evening

That will know our names only in a different

Pronunciation, and then, and only then,

Might the profit-taking of spring arrive…

—John Ashbery, “April Galleons”

A taste for Asian things is often associated with Commodore Matthew Perry’s “opening” of Japan in 1853–1854, and the subsequent vogue, among French Impressionist painters and American architects, for the beguiling asymmetries and exquisite workmanship of a half-imagined East. But a horizon-expanding exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, a historic hub of international trade, shows that the prodigious appetite for Asian luxury goods—graceful porcelain jars, gilded folding screens, shimmering lacquered chests, colorful Indian bedspreads—began centuries earlier, in a Pacific pivot that long preceded Commodore Perry and President Barack Obama, and with startling aesthetic results. Spanning the seventeenth to the early nineteenth century, the show brings together nearly one hundred objects in every medium imaginable, including feathers and seashells, from four continents.

Beginning in 1565, bulging Spanish galleons and the even larger Portuguese carracks crisscrossed the world—from Manila to Acapulco, from Brazil to Lisbon, from Havana up to Boston—transforming, in the vertiginous process, both the global economy and local artistic practice. What began primarily as an exchange of American raw materials like silver and gold for Asian spices (especially pepper) and tea mushroomed into something much more significant, as exotic Asian handicrafts of all kinds captured the imagination of Western elites eager to show off their cosmopolitan reach, and inspired a countertrade of “Made in the Americas” knockoffs and creative variations. “So excessive is the love of Chinese architecture become,” joked an Englishman in the 1750s, “that at present the foxhunters would be sorry to break a leg in pursuing their sport over a gate that was not made in the Eastern fashion of little bits of wood standing in all directions.”

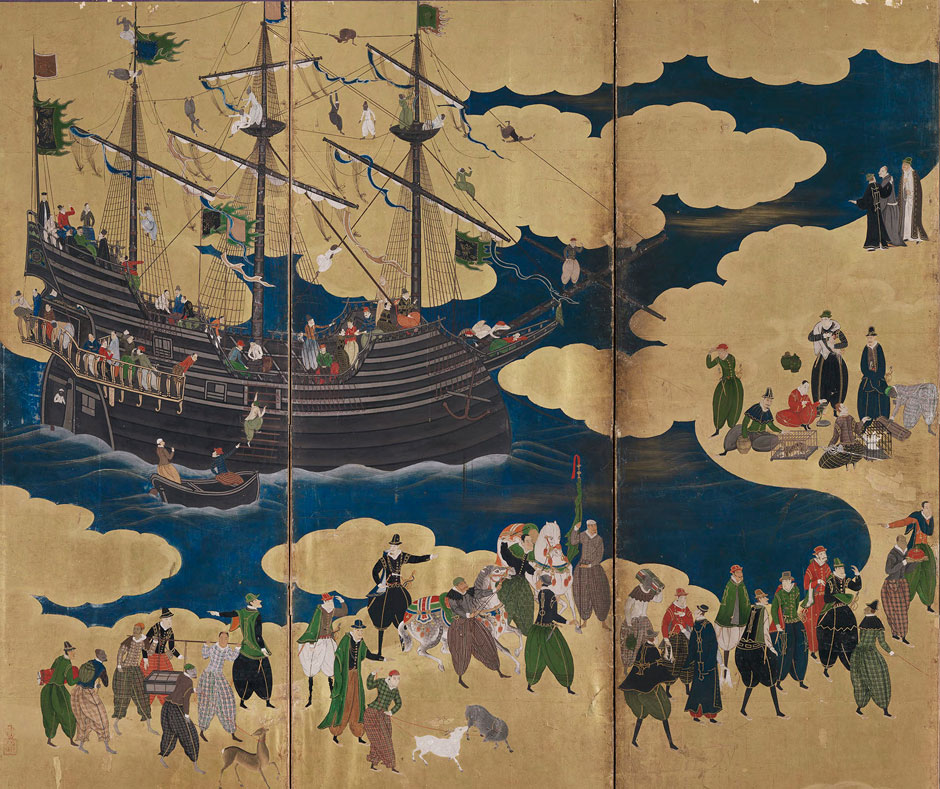

Before long, the holds of these floating cabinets of curiosities could barely contain all the luxury goods demanded by Mexican viceroys, Canadian missionaries, and New England merchants. Piles of crates were lashed to the decks while more crates were suspended from the sides, as shown in a painted folding screen depicting a fully loaded Portuguese ship off the coast of Japan, circa 1600.

Chinese made-for-export ceramics—a kind of world currency by the eighteenth century—were so popular in Brazil that there were roofs in the city of Cachoeira, in Salvador de Bahia, sheathed in blue-and-white porcelain, as though tiled with the very sky and clouds. The New England Puritan minister and poet Edward Taylor marveled at a piece of what came to be known simply as “china”: “We gaze thereat and wonder rise up will.” A native Mexican chief, named Tonati, put in an order for a set of Chinese dishes, the “vessel of choice” for consuming chocolate.

The cargo on European ships wasn’t limited to such manufactured treasures; a human cargo of “chinos” (the generic word for Asians of all nationalities), whether skilled artisans or slaves, was squeezed in among the crates, and exchanged at markets in Mexico City along with the tableware, bringing new ideas—along with human blood and toil—to local industries.

The east-west trade in fragile and expensive luxury goods, with steep markups for transport and middlemen, created ideal conditions for what we would now call disruption, as cheaper, locally-made things imitated, or creatively riffed on, the “authentic” originals. The curators of the Boston show grope for words to describe the astonishing cultural handoffs that ensued: “hybridity” and “synthesis,” adoption and adaption. Meanwhile, the viewer, puzzled by so much fusion and confusion, is often left to wonder, “What exactly am I looking at?”

Sometimes, the cultural mixing was a simple matter of showing off one’s cosmopolitan sophistication and mercantile reach. Receiving company at home, self-styled Boston “Brahmins” donned turbans and wrapped themselves in long, loose robes from India known as banyans. In John Singleton Copley’s portrait of around 1769, the foppish merchant Nicholas Boylston leans self-importantly on a pile of heavy account-books, presumably documenting his commercial transactions, while the ocean from which his riches derive shimmers pacifically behind a lifted curtain in the background.

But the cross-fertilization could run much deeper, as indigenous artists in the Americas discovered ingenious ways to compete with Asian prototypes. Quetzal birds replaced phoenixes in the tin-glazed majolica—much cheaper than the Chinese porcelain it resembled, and often just as visually arresting—manufactured in the bustling city of Puebla, southeast of Mexico City. Lacquer-ware techniques developed by Native American artists centuries before European contact were applied to new objects for rich buyers. A sumptuous portable desk from around 1684, which looks vaguely Japanese but was actually made in Colombia, displays a coat of arms sheltering a basket of tropical fruit, flanked by native parrots.

Advertisement

A bedcover woven in Peru around the end of the seventeenth century is a triple mash-up of motif, method, and material. This vigorous American hybrid replaces Chinese animals with alpacas and viscachas (“silky-furred rodents native to the high altitudes of the Andes”) and the phoenix with the local condor. Imported (and expensive) Chinese silk has been picked apart by local artisans and rewoven with an equal share of llama or alpaca fibers, using indigenous Andean weaving techniques. The red background—conveniently symbolizing good fortune in China as well as luxury in Peru—is made of cochineal, the brilliant dye harvested from cacti-devouring insects.

“Deeply acculturative” examples like these, belonging to no single cultural tradition, have languished in museum storage for decades, considered little more than fakes or cheap rip-offs. For this exhibition, such cultural impurity is an occasion for celebration rather than censure, as a precursor of our own interconnected world. Where else could one encounter the uniquely Mexican genre of enconchado (shell inlay) painting, in which, for example, the Jesuit missionary Saint Francis Xavier, embarking for Asia—a motif borrowed from a Dutch print—dons a robe of actual mother-of-pearl overlaid with oil paint, with the frame decorated with bird-and-flower motifs borrowed from fine Japanese lacquer-ware?

What lingers in the memory, as a kind of afterglow of the exhibition, is the sheer creative energy, and frequent sly wit, of much that is on view. The artist who embroidered willowy Chinese maidens wandering near a New England redbrick house, on a curtain “possibly” made in Boston, must have found this fantasy landscape as outlandish as we do. And surely the Ursuline nuns in Quebec were in on the joke when they depicted, on a decorative altar covering, pagodas alongside Algonquin longhouses. And why exactly did the wily nuns adopt the particular colors they employed? Because it was well known, as a Jesuit missionary at the time remarked, that the Huron Indians always responded well to “a fine red and fine blue.”

“Made in the Americas: The New World Discovers Asia” is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston through February 15, 2016. The catalog of the exhibition, by Dennis Carr, is available from the museum.