Constructed of sturdy materials and meant to last decades, even centuries, architecture may seem to have little in common with comics, which are printed on cheap paper and prone to being thrown away by one’s mother. Yet the two mediums not only have a natural affinity, but the multi-panel drawing format can do several things that other visual methods cannot to advance broader knowledge of the building art.

An intriguing new exhibition, “Arkitektur-Striper: Architecture in Comic-Strip Form,” at Oslo’s National Museum-Architecture provides a fascinating overview of this phenomenon. Co-curated by the Norwegian institution’s Anne Marit Lunde and the Vienna-based cultural anthropologist Mélanie van der Hoorn (whose 2013 book Bricks & Balloons: Architecture in Comic-Strip Form served as the basis for the show), it proves why a once déclassé graphic genre is able to explain buildings to the general public better than even the most immersive virtual-reality techniques.

Studio Asynchrome

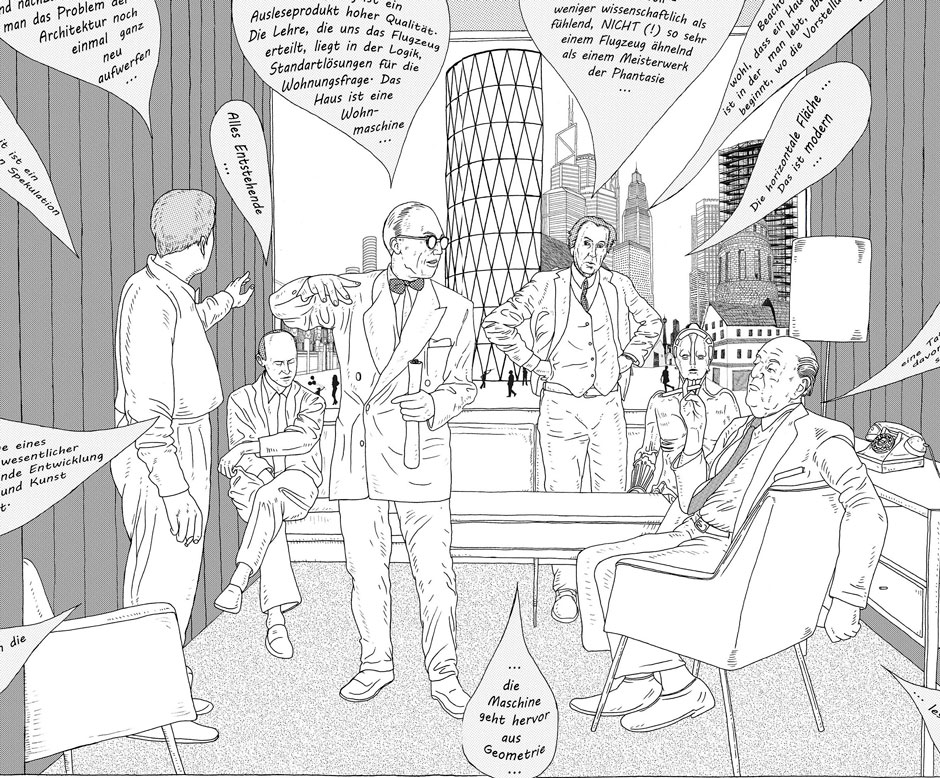

From left, Theo van Doesburg, Rem Koolhaas, Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, the robot Maria (from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis), and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, in Marleen Leitner and Michael Schitnig’s Niemandsräume–Eine utopische Spurensuche (No Man’s Spaces: In Search of Utopia) (detail), 2014

Comic strips can vividly illuminate a sequential story, and thus bring alive the often long, tedious, disjointed, and arcane process of architecture. Because so many comics are still hand-drawn, they can portray urban settings that feel much more emotionally alive than the super-slick, digitally altered photos now favored by real estate developers to make their unexecuted plans look as real as possible.

Two parallel but intertwined threads run through “Architektur-Striper”: comics that use architectural motifs, and architects who draw on the conventions of comics to present their designs. Not surprisingly, many modern master builders—like their fellow avant-garde artists in other mediums—drew on pop cultural forms to give their work a more contemporary feel.

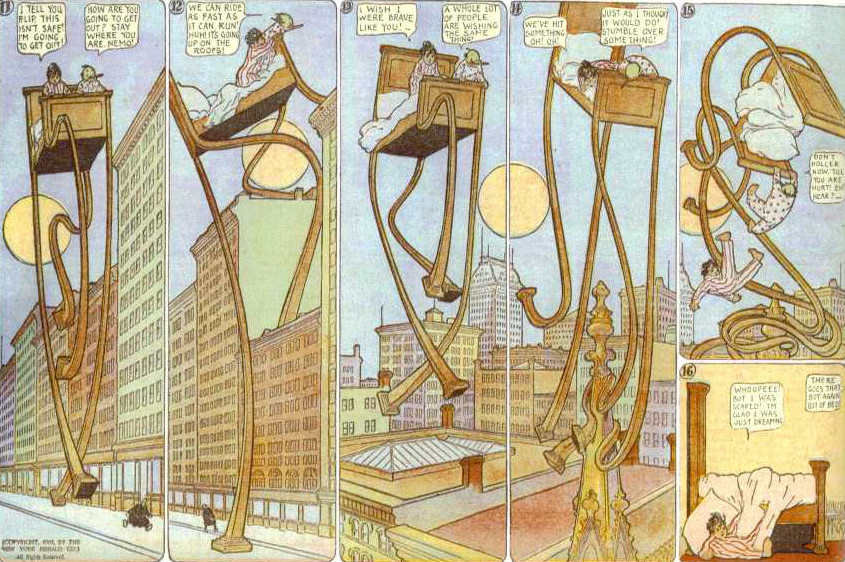

Although the exhibition (and its brief but well-illustrated catalog, with texts in both Norwegian and English) is heavily weighted toward postmillennial examples, it begins with one of the greatest exponents of architecture in comic strips, the American artist Winsor McCay. In his various newspaper cartoon series, especially Little Nemo in Slumberland (1905-1914 and 1924-1925), McCay frequently evoked the skyscrapers that transformed American cities during the first decades of the twentieth century, and implied that these unprecedented wonders emanated from the realm of dreams. His reality-based fantasy structures had much in common with the futuristic metropolis of vertiginous towers and traffic bridges displayed on the cover of King’s Views of New York, a popular turn-of-the-century photographic compendium that charted the period’s vast changes in urban development.

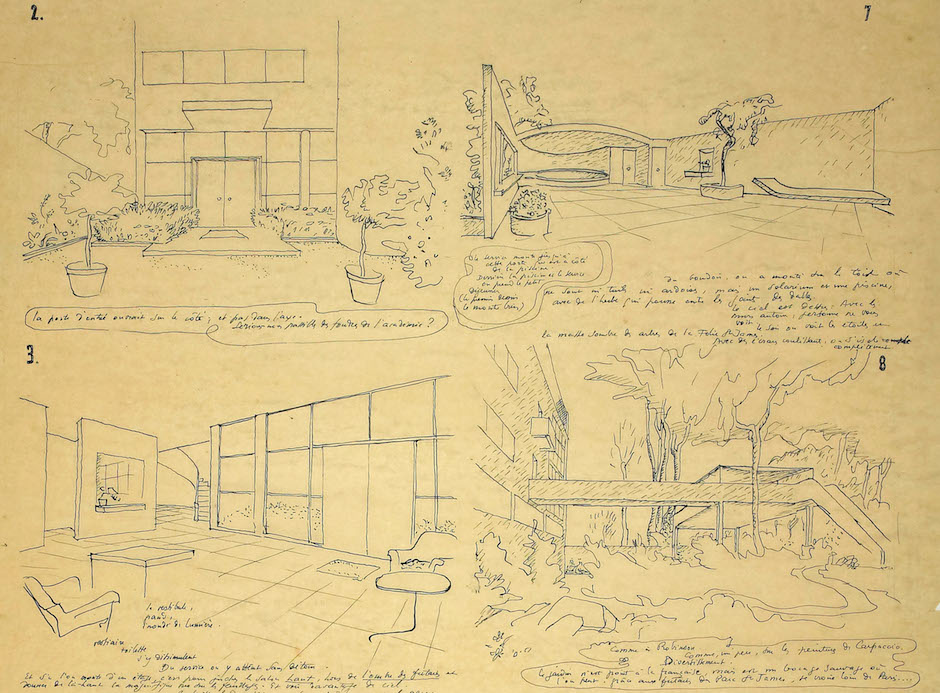

Among architects’ own engagement with McCay’s medium, one particularly intriguing early piece in the Oslo exhibition is the antithesis of the gorgeous but pompous watercolors typically offered by Beaux-Arts-trained builders. Although not, strictly speaking, a comic strip, Le Corbusier’s 1925 illustrated letter to the prospective client of his unbuilt Villa Meyer for the Paris suburb of Neuilly uses nine cartoon-like panels with written captions to describe what the proposed house would look like inside and out. This was a shrewd marketing strategy by an architect so innovative that even the most knowledgeable connoisseur might have been unable to fully comprehend his concepts through conventional renderings.

One glaring absence in “Arkitektur-Striper” is material relating to America’s classic mid-century comic books, in which striking depictions of the modern city were as central to the narrative as omnipotent protagonists like Superman and Batman. Both those characters figure prominently in the small and disappointing show “Superheroes in Gotham,” on view at the New-York Historical Society concurrent with the Oslo exhibition. Despite the emphasis suggested by the title, the New York show is almost devoid of comics with architectural settings—all those moody skyscraper canyons through which Clark Kent’s alter ego flew and Bruce Wayne’s drove his Batmobile—and overloaded instead with kitschy showbiz memorabilia and fanboy merchandise.

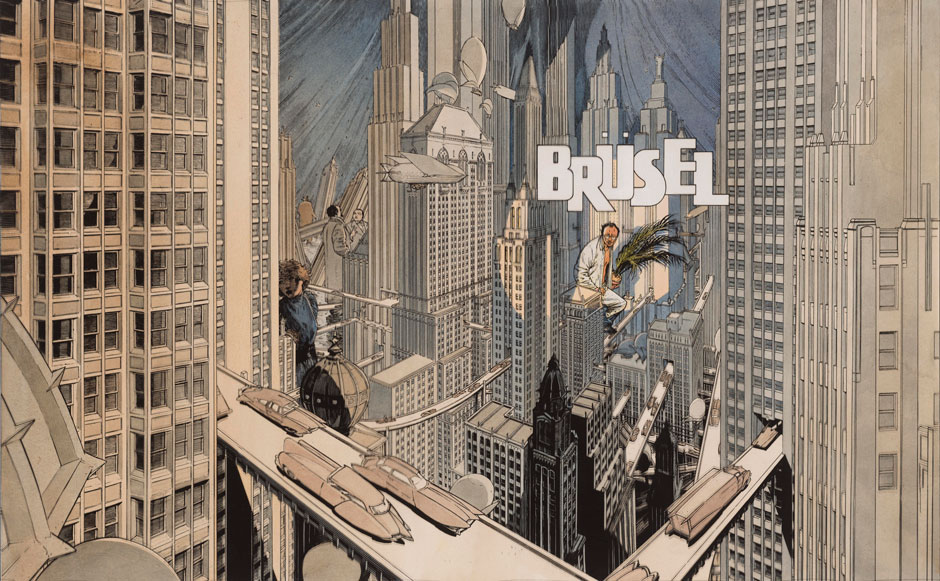

The Norwegian show does not explore this era either, but some of the brooding urbanism typical of old Batman and Superman comics can be found in some of the later works it features, such as the Belgian artist François Schuiten and writer Benoît Peeters’s noirish 1992 graphic novel Brüsel (the penultimate publication in their marvelous six-part series Les Cités Obscures). The plot deals with a wholesale urban modernization of the sort that threatened the historical character of the Belgian capital during the 1960s and 1970s, with an emphasis on replication and simulacra that might seem familiar to readers of Peeters’s biography of the philosopher Jacques Derrida.

Advertisement

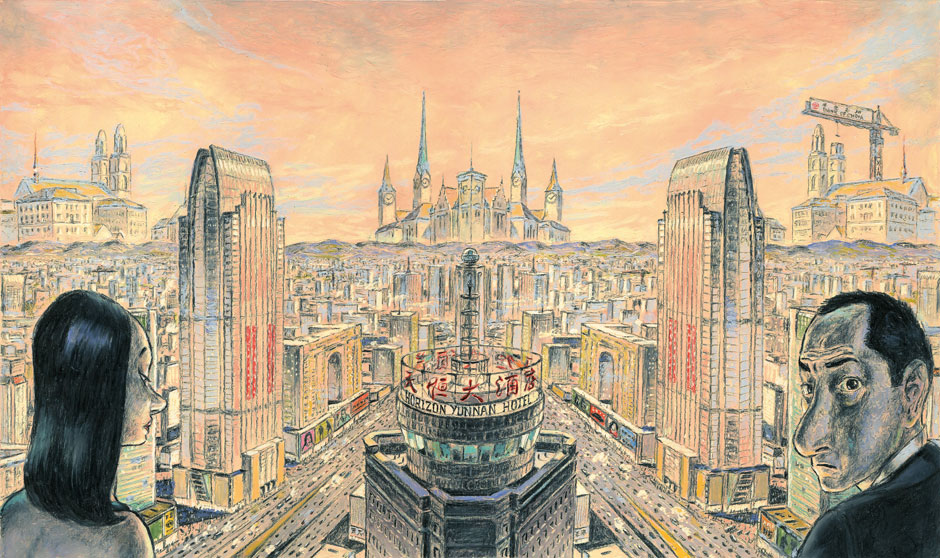

Similarly, the Swiss artist Matthias Gnehm’s 2014 masterpiece Die kopierte Stadt (The Copied City) deals with a megalomaniacal Chinese oligarch who creates a full-scale replica of Zurich in Kunming, based on a million photos of the original—a mordant commentary on the current mania in China for aping Western landmarks. However, one misses Chip Kidd and Dave Taylor’s breathtakingly cinematic graphic novel Batman: Death by Design (2012), with its sinister master builder who bears more than a passing resemblance to the grandiose architectural genius Rem Koolhaas.

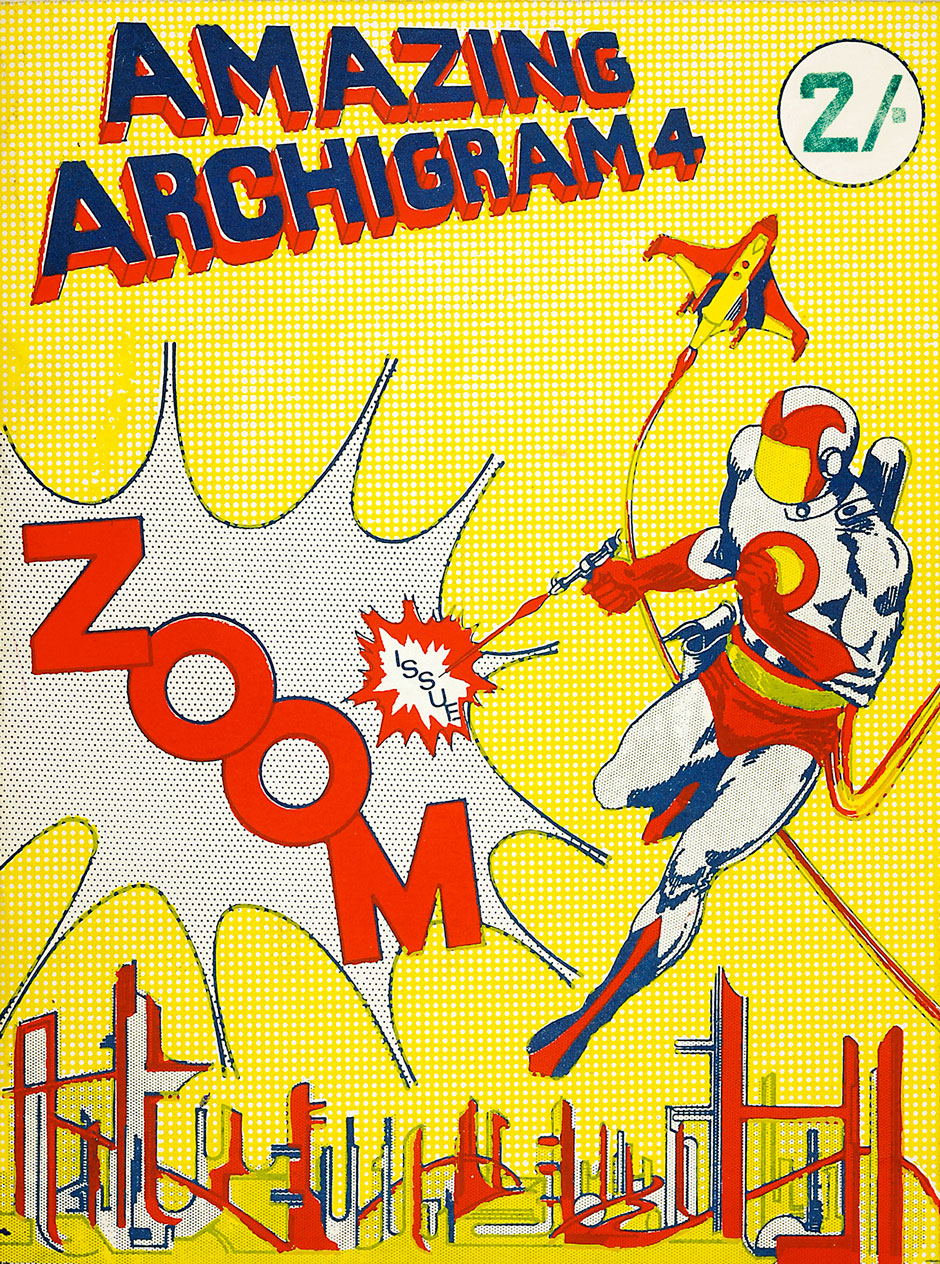

With the rise of Pop Art in the 1960s, avant-garde architects rediscovered cartoon stylization as a way to give their experimental ideas a high/low panache. Several breakaway collectives published their manifestoes and projects in comic book form, among them London’s Archigram group. The Oslo presentation includes Space Probe, the 1964 cover illustration by the architect Warren Chalk for that firm’s eponymous magazine. Directly influenced by Roy Lichtenstein’s contemporaneous benday-dotted Pop paintings, this dynamic image features an airborne, space-suited superhero zapping his ray gun, while an onomatopoeic “ZOOM” explodes above the framework of an unfinished structure.

Ever since then the comic strip has remained an integral part of architecture’s visual vocabulary, and increasingly so with the globalization of the profession, no doubt because this universally understood format can transmit even complex ideas without language. That mute communicative power is obvious in the work of the French architects Alexandre Doucin and Felix Wetzstein’s Hollywool (2010), a nearly wordless visualization of how abandoned commercial structures can be turned into economically viable agricultural operations (in this case sheep farming for wool production). Their widely applicable proposal could be understood just as easily in Senegal as in Sumatra.

“Paper architecture”—drawing hypothetical schemes when construction is impractical, implausible, or impossible—is a venerable tradition in the building art, especially in periods of economic hardship when construction prospects are low but imagination runs high, such as the early years of Germany’s Weimar Republic. But the comic-strip form has encouraged a singularly audacious streak of architectural creativity, perhaps because of the pulp booklets’ strong sci-fi associations.

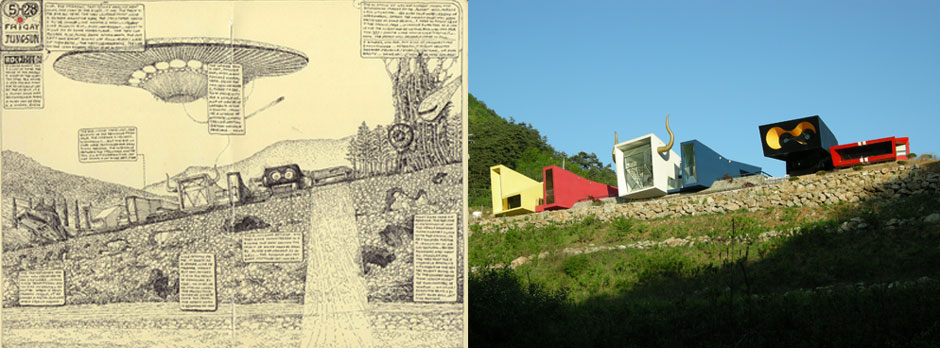

Several compositions in the Norwegian survey exude the obsessive wackiness of outsider art, especially those by the Korean architect Moon Hoon, whose very name seems to promise extraterrestrial thrills. One memorable 2010 Hoon drawing shows a flying saucer hovering above a bizarre South Korean ski chalet comprised of several adjacent, conjoined volumes, one of which sports a huge pair of bovine horns. Another of his conceptual sketches from that year, Wind Museum, diagrams an enigmatic beak-shaped tower that now looms over a cluster of suburban houses he recently completed on a windswept volcanic island off the South Korean coast.

But this exhibition is not all fun and games. The social consciousness on the rise among young architects worldwide is exemplified by the Venice-based architectural office Studio Tamassociati’s powerful storyboard Destinazione Freetown (2012), an account of a hospital the firm erected in the capital of Sierra Leone. Though the hospital is an elegantly proportioned, low-rise modernist structure that any advanced Western country would find itself lucky to have, these architects are well aware that design excellence alone cannot solve the developing world’s most urgent problems. They use the comic to address the petty corruption that can undermine even the noblest intentions of the international aid community. In one panel a Western doctor upbraids a shady local entrepreneur: “This is a pediatric centre, not a marketplace!” But another caption urges us to “listen to the story of this hospital and who backed it; it’s a story of solidarity, somewhere between dream and reality.” The same can be said for “Arkitektur-Striper” and the ink-stained visionaries it rightly honors.

“Arkitektur-Striper: Architecture in Comic-Strip Form” is at Oslo’s National Museum-Architecture through February 28, 2016. A catalog, “Arkitektur-Striper: Architecture in Comic-Strip Form,” is published by the museum.