Investigative reporting got a boost in 1976, after the movie All the President’s Men showed what a small team (two men) could do if an editor and owner like Ben Bradlee and Kay Graham at The Washington Post let them keep digging for a long time. Another such coup was brought off by The Boston Globe in 2002, when its own investigative team of four people, called “Spotlight,” broke the story of Cardinal Law’s protection of priests who sexually preyed on children. In this case, Spotlight, which normally chose its own subjects, had not followed up on leads fed to the paper. It took an outsider, Martin Baron (played by Liev Schreiber), who had become editor of the paper in 2001, to jog the team into action. Baron was sent by the Globe’s new owner, The New York Times, to trim costs, yet he spent heavily on the priestly abuses scandal. An instinctive deference to the Church had inhibited the press in this Roman Catholic city from recognizing a scandal in its own backyard. Baron was not subject to that thrall. He was initially thought of as outside the Boston culture—an unmarried man, a Jew, not interested in the sacred Boston Red Sox.

In Tom McCarthy’s Spotlight—which has received six Oscar nominations, including for Best Film and Best Director—The Boston Globe story has been given a movie treatment like that of The Washington Post story. Both films retain some of the clichés of such tales—the resistance of society to what the enterprising reporters are trying to do, the difficulty of prying evidence from fearful witnesses, the final victory of the good guys over powerful resistance. But there are many differences. Woodward and Bernstein were outside the normal political reporting of Washington. The “Spotlight Four,” though not churchgoers, were all Catholic-raised or influenced. The crimes being investigated were more personal and religious, combining sexual and theological inhibitions.

As the team begins, lethargically, to go into the one case that had been superficially handled in the Globe, the serial abuses and regular moves of Father John J. Geoghan, they saw that other priests had been treated the same way—four, they turned up; then eleven. In diocesan records they began tracing the patterns of such frequent shiftings-about for priests. They were stunned as they found that large numbers of priests fit the pattern. They called on Richard Sipe, a former Benedictine monk and psychotherapist who has studied priestly sexual activity for decades. (He is a respected scholar whom I have consulted for my writing and speaking on priests.) He tells the Spotlight team over the phone (his voice supplied by the actor Richard Jenkins) that he had found a high quotient of predatory priests in America, almost uniformly protected by bishops, and by that quotient the number of offending priests in Cardinal Law’s domain would be ninety—which was eerily close to the number they had turned up in diocesan records—seventy-six.

The team now had to interview the priests and find their victims. The priests were protected by Cardinal Law, and many victims did not want to be reminded of their shame. The feisty leader of the team, Walter “Robby” Robinson (played by Michael Keaton), talks to people from his high school to find out what a coach did there, and continuously pressures a golfing pal who is a lawyer for the diocese to speak with him candidly. Over and over he is told he cannot write this story. But he threatens back, telling one man, “You do not want to be on the wrong side of this story,” and telling another that there are going to be two stories, one of the priests and bishops who committed the crimes, the other of the people who covered them up. “Which one do you want to be in?” These are uncomfortable bits of dialogue, since it soon develops that even the Globe is part of the cover-up story.

An early member of the important (then nascent) organization SNAP—Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests—brings in records of abuse, and the team asks him to turn them over. He says he already did give them to the paper, five years ago. From this time on, the mystery grows—where had those records gone? Keaton’s Robby gets more stunning news when a lawyer he has been pressing to tell him about his work for the diocese tells him he had turned over a long list of priestly abusers twenty years ago. What happened to them? We are bound to suspect Ben Bradlee, Jr. (played by John Slattery)—the Globe’s deputy managing editor and the son of the legendary Washington Post editor who exposed the Watergate scandal—since he has been skeptical all along about the possibility of prevailing over the Church’s many allies, and considering lawyers for the victims just cranks.

Advertisement

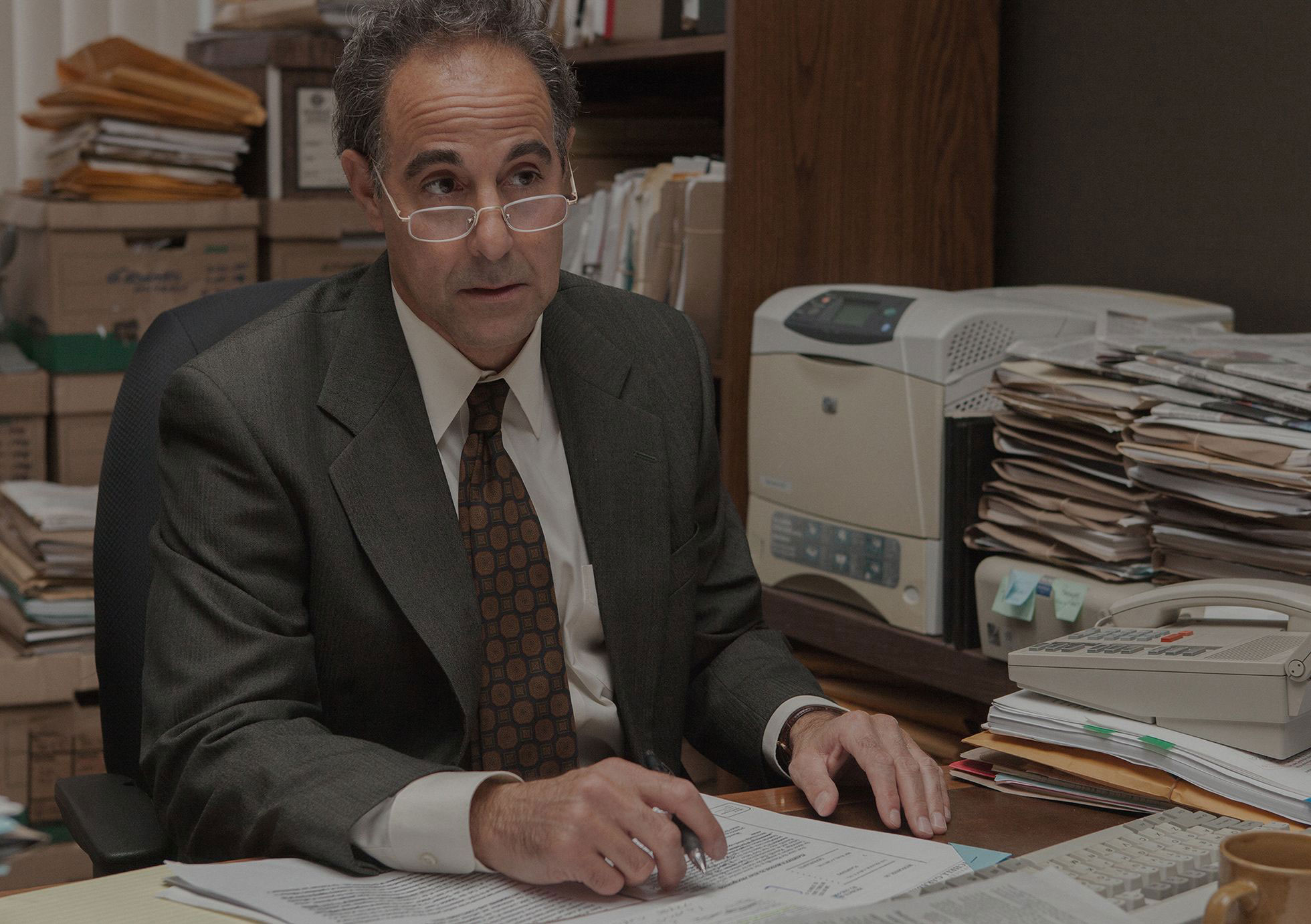

The script, written by the film’s director Tom McCarthy and the academic- and-showbiz marvel Josh Singer, is amazing in its mastery of the complex material, since many strands converged for the paper to break the hold of the hierarchy over the city—not only records of priest moves, testimony of victims and predators, but correspondence of the Cardinal and other bishops that were obtained by court action but put under a seal that the Catholic judge refuses to lift. That bottleneck is broken by one lawyer for the victims, actually a compound of several lawyers working for the abused. This man, plodding on with bent back and no time for frivolities, is played by Stanley Tucci, who is normally the best thing about any movie he is in. His character, an Armenian, Mitchell Garabedian, has been defeated too many times to give in to the pestering of the hothead on the Spotlight team, Mike Rezendes (played by Mark Ruffalo); finally he indicates that some of the sealed material was attached to one of his cases and is outside the ban, but the documents have been removed (“Boston is a Catholic city”). Rezendes scrambles for a judge to return the removed documents—and he wins.

Now the paper has a case solid enough to be published. But Robby opposes publication. He now wants to bring down the whole nationwide system of Church corruption. Boston can wait for that bigger story. But the momentum is too great to be held up and the story goes to press. There is a stock picture of the presses rolling, the triumph scene of many journalism movies, but there is not universal jubilation. One member of the team has to break the news gently to her pious grandmother. Rezendes takes one of the first copies off the press to Garabedian, who receives it wearily because he is interviewing new victims.

There was a crucial scene before publication, when the investigative team met with their superiors, Baron from the Times, Ben Bradlee, Jr. from the Metro section, and a representative of the paper’s legal department. They are facing the fact that a lawyer hounded by Robby finally said that he turned over a list of victims to the Globe twenty years ago. Ben Bradlee, Jr., the man we have been suspecting of burying that list, was not at the paper twenty years ago. The lawyer says he turned it over to Metro. Ben Bradlee, Jr., looks at Robby and says, “It was you. You were Metro.” Robby, with blank eyes says, yes, “It was me.” As others look at him in amazement, he mutters, “I forgot.” His early zeal on the quest makes this claim convincing. People do forget what is unpleasant, or what would be a terrible disturbance in a city with many ties of loyalty and dependence. But in a carefully calibrated shift Keaton manages perfectly, a memory has been growing that is a burden and makes him not want to reach the goal he began to chase so well.

At this point, with the Spotlight team sitting there irresolutely, Schreiber caps a calmly powerful performance as the outsider who put the investigation into motion. He says that when people have been in the dark a long time, and the light is suddenly turned on, they are stunned and disoriented. He softly pronounces that he knows only one thing now, that a difficult task has been done very well. He is advising the others to forgive Robby. But does Robby forgive himself?

We get the answer in the very last scene. The team has come back to the paper on the day after the story appeared, and the phones in the Spotlight are ringing with reports from new victims, who know now they will be heard. Rezendes and Robby are just in the door when they are told to pick up the phones and take down the victim information. Rezendes is quick to move to his phones, but Robby hesitates at the door, and the expression on his face is not of elation but anguish. Then he walks to his desk at the far end of the office, turns back to face the room jangling with phones, looks disconsolate for a moment, then picks up his own phone. We are not told, but we know, that he is thinking of all these kids whom he could have protected twenty years ago. The whole city, including its paper, was complicit.

Advertisement