With the results of Tuesday’s nearly dozen contests, most of them in the South, both parties are well on their way to having their candidates. But they’re a long way from having internal peace. The collapse of the Republican Party, which has been foreshadowed since last fall, if not before, is now taking place before us. The probably unstoppable candidacy of Donald Trump—who won seven states on this so-called Super Tuesday—bears witness to the broad rebellion against the Republican Party establishment. Ted Cruz’s victories in three states do not present a realistic threat to Trump’s arriving at the Republican convention with enough delegates to win the nomination. And while it’s virtually certain that Hillary Clinton, who won seven states (as well as the territory of American Samoa) to Bernie Sanders’s four, will be in a position to take the Democratic nomination, repairing the fissures within her party could prove a challenge. It would take a major explosion to dislodge either front-runner.

All sorts of maneuvering is going on to attempt to rescue the Republican Party, but its leaders face a major conundrum: how to transmogrify themselves. Can Republican members of Congress and in the upper echelons of the party hierarchy possibly understand that they are the problem, that the breakdown stems from an institutional detachment from reality—and from a failure to understand today’s Republican base? The leadership had proceeded on a number of illusions: that the base could be mollified by making unfulfillable promises—to repeal Obamacare and balance the budget—while their own emphasis was on cutting taxes on the wealthy and corporations, paring entitlements, expanding trade, and helping out businesses that want cheap immigrant labor. They thought that they could toy with racism—a strategy that began with Richard Nixon—without it capturing the party.

Trump, who rolled up Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Massachusetts, Tennessee, Virginia, and Vermont on Tuesday, is probably the most famous and opaque presidential candidate in a very long time. His campaign organization is sui generis: he travels on his own plane with only a couple of aides, including his campaign manager, Corey Lewandowski, and his campaign staff is relatively small and essentially out of sight (in plain, windowless offices in what used to be the set for Trump’s now defunct television program, The Apprentice, in the gilded Trump Tower on 5th Avenue). His campaign staff is large enough to arrange huge rallies (no small feat) and to manage field operations in states Trump contests, though, according to Politico, Trump isn’t spending much of his own money on the race: most of his funding comes from donors and his own contributions are loaned or in kind. The campaign has no pollster; he isn’t guided by focus groups. Much of the strategizing comes out of his own head. And unlike other campaigns, Trump has no group of senior advisers whose names are known in political or academic circles.

The dark side of the real-estate billionaire has become more apparent in recent days—even as he comes close to accumulating enough delegates to win the nomination. In Trump’s venturing to pretend on Jake Tapper’s Sunday show State of the Union that he didn’t know who David Duke is—a couple of days after he’d foresworn his endorsement—he uttered some quotes that could be devastating if he’s the Republican nominee: “I don’t know anything about David Duke.” “I don’t know anything about white supremacists.” “I don’t know David Duke, I haven’t met him.” On the day before the Super Tuesday primaries, Trump pointed out that he had foresworn Duke before. He said that the problem Sunday was a “lousy earpiece” supplied by ABC. But this didn’t reassure Republican leaders.

It’s hard to fathom what, exactly, Trump knows about public policy. He’s intellectually lazy and he evinces no respect for knowledge itself. What does he read? Why does he persist in marrying fashion models? Does he not comprehend that there may be a problem with his retweeting the ravings of hate groups or a saying of Mussolini? How could he not get the joke of the Twitter bot @ilduce2016, showing Mussolini’s profile with Trump’s hair? The satirical website Gawker set up this account last year for the purpose of trapping Trump. What seemed on the edge to suggest not long ago—that Trump’s candidacy has an aura of fascism, in the behavior of both the candidate and his unquestioning followers, is now widely discussed. His concept of governing, of which he’s been asked almost nothing, was made clear when he held his “press conference” instead of a victory speech Tuesday night at his Palm Beach home, standing at a gilt trimmed podium, with American flags arrayed behind him and Chris Christie standing there as if his lieutenant or vice president. Asked about the speaker of the house, Trump said, “Paul Ryan, I’m sure I’m going to get along great with him. And if I don’t, he’s going to have to pay a big price—okay?”

Advertisement

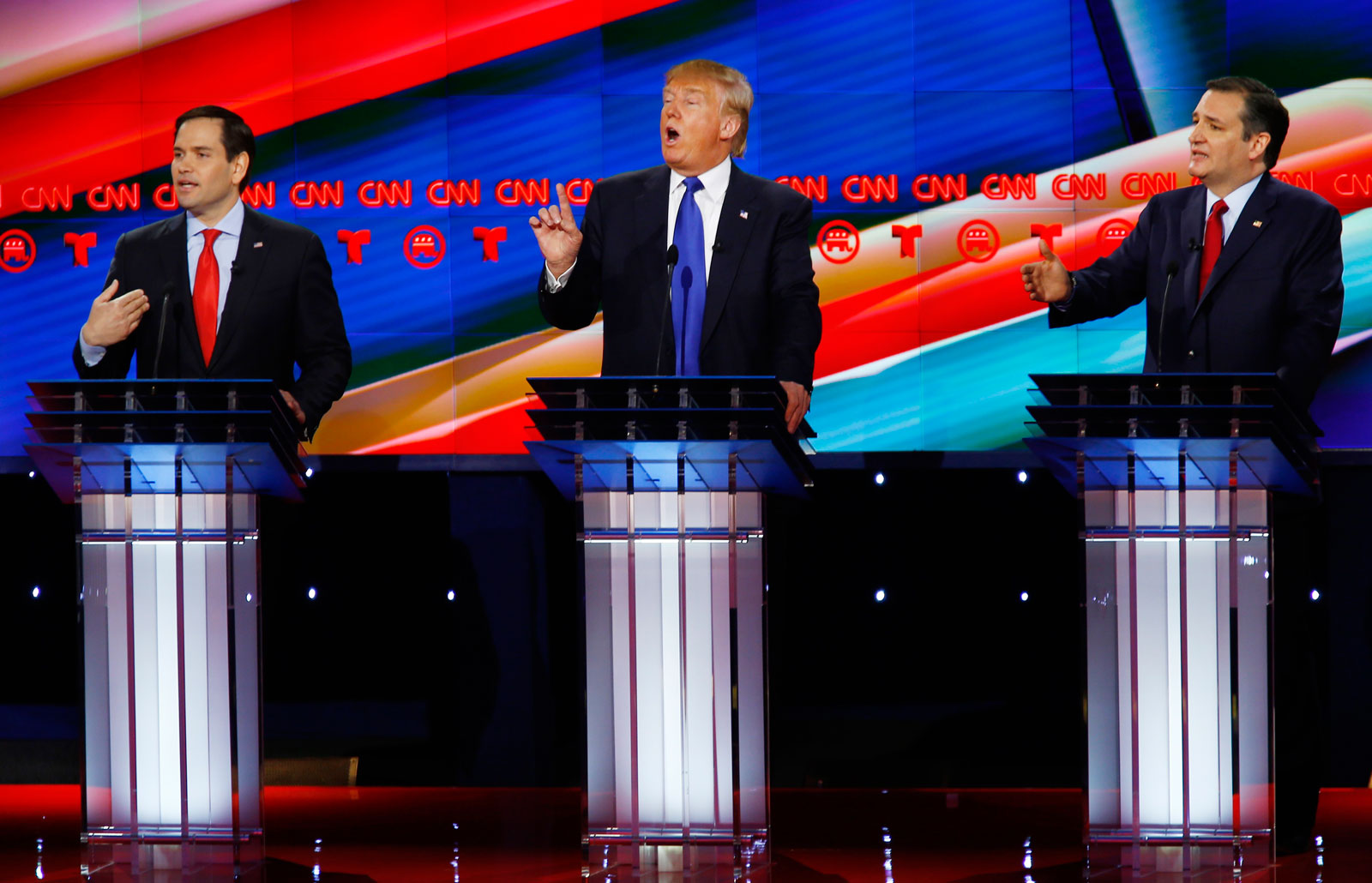

Rubio may have been more successful than Cruz in showing in the February 25 debate that Trump can be vulnerable. He brought up some questions about Trump’s business—which Trump has made the foundation of his campaign by emphasizing his identity as a smart and capable executive—such as his four bankruptcies, and poked some holes in Trump’s claims about the wonderful company he claims to have founded. But the youthful-looking Rubio, lacking much of a record of achievements of his own, also invited further concern about his own maturity. After the debate, many observers in the media suggested that Trump’s opponents should have taken him on sooner, though they had previously acknowledged that Trump’s unerring radar for a rival’s weakness—Jeb Bush’s “low energy”—was an understandable reason for them to hesitate to take him on.

The press also bears some responsibility for Trump’s being allowed to sail so far through the campaign largely unquestioned about his position on issues, his business practices, or his claims about what he would achieve without difficulty as president. First, there’s the way the debates are covered. The media treasures conflict. (I once moderated a substantive primary debate and was criticized in Time, not atypically, as having “served watercress sandwiches.”) And conflict can boost the television ratings. Throughout most of the February 25 debate the camera was on the three candidates yelling at each other; it was considered great entertainment even as it was deplored. While all this mayhem was going on John Kasich was being presidential: he answered questions thoughtfully, he showed he understood the role of a leader, and he talked common sense. But that wasn’t newsworthy.

Then, there’s the nature of what is considered news. If a newspaper has previously covered something in the past—say, allegations against the Trump University as a valid business school—there was no reason to bring it up again. “We’ve covered that,” one often hears. This response of course overlooks the fact that many of their readers may have missed the story when it first ran, or, more to the point, that the story didn’t have the same salience it does when the subject is running for president. Anyway, why couldn’t some of these questions have been raised at candidate press conferences or in appearances on the Sunday talk shows, where the questions tend to run toward, “How do you think you’ll do in [name the state]?” And in the debates themselves, why haven’t the moderators brought up questions about Trump’s livelihood? It’s reported that the question Trump hates most is whether he’s as rich as he claims—$10 billion. (The “town halls,” put on by CNN, where each candidate is questioned separately, have been far more substantive.)

Trump has shown that he can be as brutal toward members of the press as to his fellow candidates. He can let fly against them in his Twitter account, which has over six million followers. He keeps the press who cover a rally penned up in a cage-like structure and makes threatening statements about them, to the delight of the crowds. A litigious character, he’s threatened numerous lawsuits against reporters and has now proposed to make the standards for winning such suits easier—by ripping up the First Amendment. (He makes Spiro Agnew, with his “nattering nabobs of negativism,” look sweet.) The journalists or producers of a talk show can feel they must take care not to so annoy the candidate that he won’t appear on their program again, or reporters that they might lose their access to him, and, as Trump is quite aware, he helps build television ratings. (It’s that fact that has caused Trump to have been allotted an extraordinary amount of free media time—far more than any of his competitors.) The history of this period may show that someone temperamentally and intellectually unfit for the presidency made prohibitive gains toward the nomination of one of this country’s two once-great parties because so many people were afraid of him.

While a few Republican office holders have endorsed Trump, most of the party members are in a state of panic. Several prominent Republicans thought they could advance Rubio’s candidacy by endorsing him on February 22, but that didn’t change election realities. The growing fright within the party is that if Trump is the head of the ticket he could take down numerous members of Congress in November. Among the more fanciful ideas to head off Trump’s nomination now buzzed about are: that the convention will select Mitt Romney, if he hasn’t already entered the race; that Paul Ryan, the ultimate insider, will be selected, though his economic policies are the antithesis of what the base wants, and the most conservative House members—the ones who deposed his predecessor John Boehner—are already giving Ryan trouble on such questions as taking up a budget.

Advertisement

Two of the current candidates have been drawing up plans of their own to snatch the nomination from Trump. Marco Rubio’s aides have talked to donors about such a plan, but until now he has only a single victory, in the Minnesota caucus on Tuesday. He managed second-place finishes in South Carolina and Virginia, but has come in third everywhere else except New Hampshire, where he came in fifth. If he loses the primary in his home state of Florida on March 15—polls now show Trump leading him by a substantial margin—Rubio will remain only a lot of people’s idea of the most electable of the presidential candidates. John Kasich is also considering a plan for getting nominated in a contested convention, but that depends upon his winning primaries in Michigan on March 8 and the state of which he’s a popular governor, Ohio, on March 15. This is actually less far-fetched than Rubio’s scheme since Kasich would have won in two major states.

The idea that Trump could be blocked at the party convention in Cleveland in mid-July assumes that his delegates, who are likely to make up a plurality of the votes, and the masses behind them would willingly step aside while the party panjandrums impose an establishment figure on the convention. And if the party establishment were to “correct” its voters by naming someone else, how likely are they to vote for that person? For yet another, the idea of a brokered convention assumes that there is some collection of people who are in a position to be brokers. But the old bosses—governors, the party chairman, and also in the case of the Democrats, big city mayors and labor leaders—haven’t been a force for nearly half a century at the conventions, which have long favored grass-roots forces demanding to be heard. There’s even been talk of the formation of a third party of traditional Republicans, but such a thing is very expensive and hard to organize, especially at this late point in an election year. Then there’s the question of who would be the candidate.

Chris Christie’s stunning endorsement of Trump last week, the day after the shouting debate and shortly before the Super Tuesday primaries, produced a cynicism in observers, particularly in the press, who thought they could no longer be shocked. In his concentrated campaigning in New Hampshire, Christie had been quite strong in his criticism of Trump: “We are not electing an entertainer-in-chief. Showmanship is fun, but it is not the kind of leadership that will truly change America.” Put through a series of questions by George Stephanopoulos about Christie’s previous criticisms of some of Trump’s more outlandish proposals, Christie assayed an explanation of these gaping contradictions between how Christie felt then and now. “You know, George, this is a February—this is February of a campaign.” Stephanopoulos reminded Christie that the Trump campaign had been underway for eight months. Pressed on how Trump would compel Mexico, a sovereign nation, to pay for his promised wall along the southern border of the United States—a fantastical idea that has been repeated so often by Trump that people now talk of it as if it might actually happen—Christie was reduced to incoherence: “Strong leadership is able to exert those things and be able to talk to folks about what advantages and disadvantages are of certain policies.”

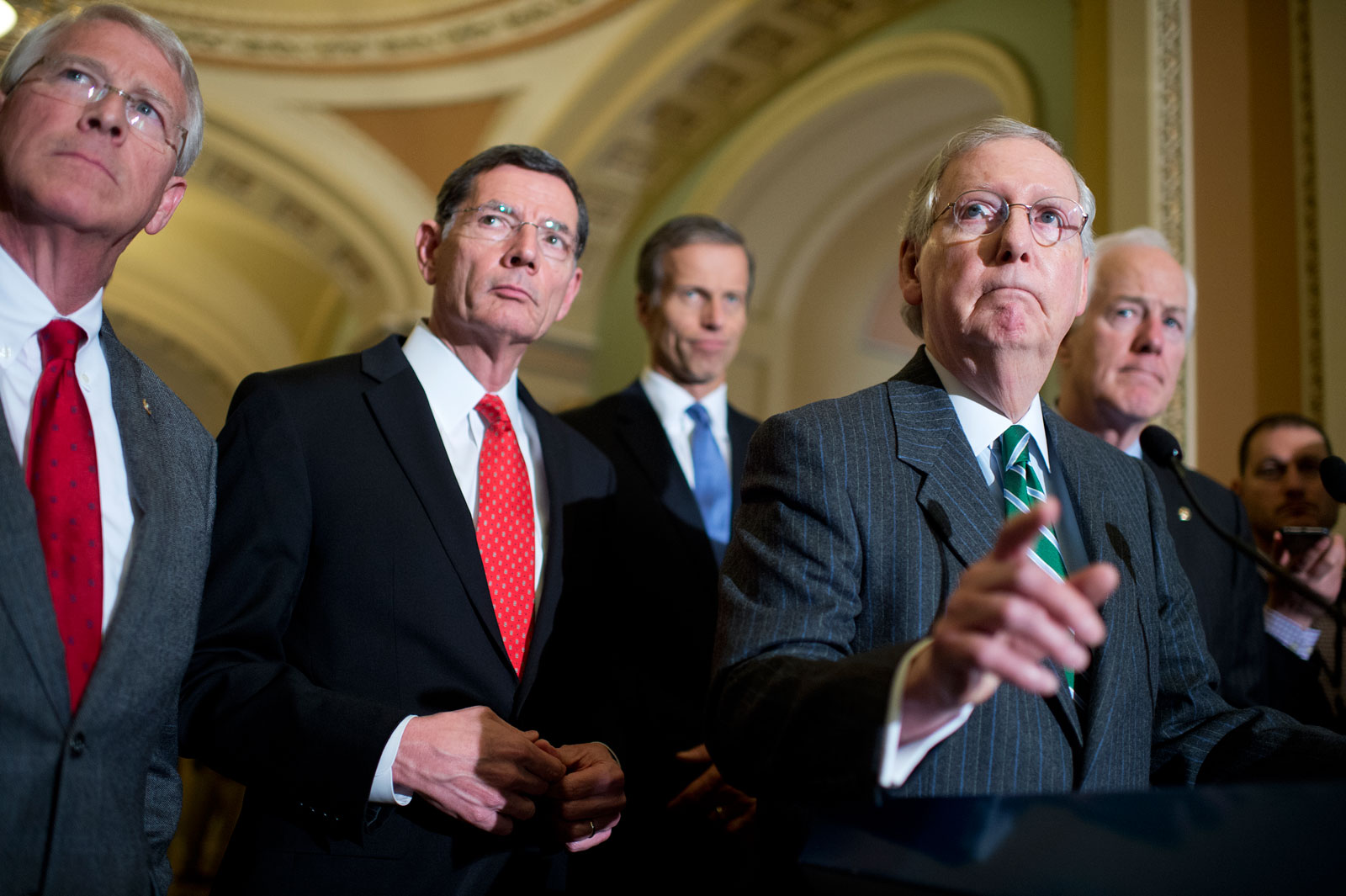

Betraying his own lack of comprehension of what’s happening within his party, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who could be in danger of losing the Republicans’ hold on the upper house, suggested that his fellow Republican senators renounce the Trump candidacy in the course of their campaigns for reelection in November. But this overlooks the possibility that if Trump is the nominee, he’s there as a result of having strong support across a wide swath of people within the senators’ states. During Tuesday’s voting, McConnell and Ryan both made strong statements against Trump for his unwillingness to denounce the KKK and white supremacist groups—to no apparent effect.

The Democratic Party hasn’t had to endure the squalid, juvenile feuding among its candidates that has characterized the Republican race, but it, too, is facing a possible big danger. The fissures between the Clinton wing of the party and that of Sanders, further to the left and also representing a rebellion against “the establishment,” are deep and may be irreconcilable. Sanders may be in the process of losing the nomination, but he still won four states on Tuesday—his home state of Vermont, plus Oklahoma, the caucus states of Minnesota and Colorado—and he’s made it clear that he doesn’t intend to give up before the convention. He sees his challenge to Clinton as a moral one, and his ability to command audiences of tens of thousands has validated him as the leader of a substantial movement. Sanders, backed by considerable forces, could well make demands about the Democrat’s convention platform, speaking slots in prime time, and the like.

The difficulty faced by both parties is that these internal schisms aren’t so much ideological as they are about insiders and outsiders—about a struggle for power—and they’re based on a profound sense of betrayal. In recent years, neither party fulfilled its promises to voters and both are seen as complicit in the great recession of 2008 and failing to adequately address its consequences. In particular, young people saddled with student loan debt are drawn to Sanders’s proposal for free college tuition at public schools. The fact that both parties failed to deliver for middle class voters may account for why numerous respondents have told pollsters that they could vote for Bernie Sanders or Donald Trump. Or, as a young man tweeted to me recently: “us [sic] younger people are tired of being screwed by the current establishment.”

Despite Clinton’s victories—beginning with her trouncing of Sanders in South Carolina and followed by Tuesday’s wins in Massachusetts (snatched from Sanders by a narrow 50-49 margin) as well as Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Texas—she will have to overcome deep resentments to unite the party. A lot will depend on how magnanimous Sanders decides to be, and also whether the identity of her Republican opponent unites Democrats behind her. Democratic turnout in the primaries and caucuses has been lower than in the last two presidential elections and the Clinton campaign may have to struggle with a lack of enthusiasm for her among Democrats in the general election. By contrast, turnout in the Republican contests has been higher than usual, which could signal that Trump is bringing new people into the process.

In South Carolina, Clinton won nine out of ten black voters—yielding her a higher percentage of the black vote than Barack Obama won there in 2008—and she continued to roll up the black vote in the southern states that voted on Tuesday. But she narrowly lost among white men there, and her campaign continues to be shadowed by voters’ negative response, in various polls, when asked if they consider Clinton “honest and trustworthy.” The issue was less damaging to Clinton in the deep South states than in Iowa and New Hampshire, but it is of course continually enhanced by the controversy over her use of a private e-mail server as secretary of state, for which she may now be facing legal problems. And there is no doubt that the matter will haunt her during the general election. Trump has already made it clear that as the nominee he would attack Clinton about the server and on Tuesday night said, “If she’s allowed to run, honestly it’ll be a sad day for this country because what she did was wrong.” He added: “Other people have done far less than her and they have paid a very, very big price.” Meaning: Clinton should be prosecuted for mishandling classified information.

Clinton’s South Carolina victory speech was the best by far of her campaign and perhaps of her political career. She spoke positively and with passion—a long way from her sing-song delivery on New York’s Roosevelt Island, where she formally launched her campaign (for the second time). And she demonstrated the shrewd political instincts that she’s often seemed to lack. Turning without saying so to Trump and the fall campaign, she said, “Despite what you hear, we don’t need to make America great again. America has never stopped being great. But we do need to make America whole again. Instead of building walls, we need to be tearing down barriers.” And she’s begun using what she acknowledges is an unusual line for a presidential candidate: “I believe what we need in America today is more love and kindness.” She’d learned to moderate her tone and even reduced the enormous crowd to a hush, though her disconcerting habit of yelling resurfaced a couple of times. But it’s the capacity for changing and improving amid the crush of a brutal schedule of travel and appearances that was particularly impressive.

Nothing has happened in the presidential election so far to alleviate the nagging question of whether a victor from either party will be able to govern. (I’m suspending judgment on whether a possible third-party candidate could overcome the formidable obstacles to winning.) The competing forces within both parties are increasingly dug in. If Clinton were to win the presidency and the Republicans maintain their majorities, it’s worth remembering that the Republican Senate (maneuvered by Cruz) shut down the government over Obamacare and also toyed with putting the country into default. The Republican House deposed its previous Speaker because he sought compromise with the president. The current Congress has told the White House not to bother to submit a budget or to nominate a Supreme Court Justice to fill a vacancy.

Our political system has only so much elasticity. Pull it too hard and it can break. The consequence of a break could be authoritarianism—the temptation toward which is in evidence now—or chaos, which would likely encourage authoritarianism. Hillary Clinton is the one major candidate taking care not to overpromise. But my guess is that way inside she knows the obvious—if she wins in November, the Republicans will seek to undermine her just as they did her two Democratic predecessors, including her husband. Our problem now is that the political parties—and their followers—seem to have forgotten that the role of politics is to resolve differences.