An especially poignant exhibit in the Foundling Museum, one of my favorite London places, is not in the current show but in the regular display. It’s a small heart, carefully woven in red thread, and it’s one of the tokens left by mothers who handed their children over to the Foundling Hospital in the mid-eighteenth century: a swatch of material, a coin, a piece of jewelry—mementos to identify a foundling if relatives changed their mind. Originally these objects were attached to the admission papers, but in the mid-nineteenth century the Secretary, John Brownlow, removed them to put them on display and raise funds, thus separating the token from the child. Painstaking research has linked many together again, but the baby whose mother left the little heart has never been identified—just a child without a name.

Thomas Coram, a retired sea-captain, established the Foundling Hospital in 1739 after years of fighting for a place of safety for the babies he saw abandoned on London streets, cast in gutters and on dung-hills. From the start artists and musicians gave their support: Hogarth was one of the first governors, the young Gainsborough painted a roundel in the Court Room, Handel put on annual benefit performances of the Messiah and bequeathed the hospital his score. The Coram Foundation still works with vulnerable children, and both the tough history of childhoods past and the hospital’s great cultural links are remembered in the brilliantly refurbished museum.

The ground floor is devoted to the hospital’s story, and upstairs, along with the Court Room, one of the best rococo interiors in London, is the grand Picture Gallery, hung with eighteenth-century paintings by Thomas Hudson, Allan Ramsay, and Joseph Highmore, a reconstruction of the room where the Governors entertained benefactors and held concerts and assemblies. The sculptor Louis-François Roubliac’s terracotta bust of Handel is here, and the upper floor of the building is devoted to Handel himself, its core being the great collection of scores, programs, libretti, and instruments bequeathed to the hospital by Gerald Coke in 1995: a major research resource for scholars.

This gives an unusually powerful setting for the hospital’s current exhibition, “FOUND,” which contains ninety-four works on this theme, contributed by nearly seventy artists, writers, and musicians, “a range of creative disciplines.” The sense of loss and of what it means to be “found” is very strong at this institution and the sculptor and installation artist Cornelia Parker—who has been the Hogarth Fellow at the museum for the past year—has curated an extraordinary show that feeds on deep strands of feeling with wit and warmth. In her brief she asked for new or existing works, or an object that people had found and kept for its significance. The only definition that she gave was that “in order for something to be ‘found,’ it has to at some point in its history have been ‘lost.’”

Some of the objects are displayed in the gallery, but others are scattered through the building, nudging against eighteenth-century furniture and portraits of men in wigs. Among Parker’s own contributions (which include deleted passages of Jane Eyre, and fragments of Jimi Hendrix’s staircase), hanging at the top of the stairs is a photograph of an American Civil War “pain bullet” given to soldiers to bite on during amputations. Ragged with teeth marks, the bullet was unearthed at Vicksburg and buried again in Freud’s London back-garden in 2003, as part of Parker’s Different Dirt: Found in America, Lost in Britain. That show too balanced despair and discovery, in Parker’s prints of objects she bought on eBay, found by amateurs with metal detectors, like simple lost thimbles, rendered precious by time, resurrected, recorded, and buried again.

That project turned archaeological conventions on their head, and this is rather similar, full of unexpected diggings and unearthings. Some found materials have been made into complete works, like the African textiles from Portobello Market that have inspired much of Yinka Shonibare’s art, including the Trumpet Boy shown here. Or Polly Apfelbaum’s string of wishbones, graded from small to large, “electroplated like baby-shoes” in copper—a string of good luck. But there’s bad luck here too, like the chain of pawnbroker’s tickets that Ron Arad found in London early 1970s. All are dated 1951, the year of his own birth, and many are marked “GWR”—gold wedding ring. Finding can provoke a shiver, a sadness.

Advertisement

Some finds—it feels wrong, somehow, to call them “works”—just emerge, fall into the hand, lurk beneath the feet, tumble out of bins, are rescued from skips, or turn up in a corner like Alison Wilding’s desiccated Cellar Frog. Bill Woodrow simply can’t remember where he found the car-bonnet and table for his 1984 sculpture Sunset: “Did I find them? Did they find me? Do you only find things when you are looking for them?” Good question.

But the casual trophies have a haunting oddity. Jarvis Cocker’s Romanian magazines, found after a Pulp gig in 1985, glow with a brashness and color you don’t associate with the Ceausescu regime, but do with the Pulp aesthetic. By contrast the old bottle that Dorothy Cross saw when diving off the west of Ireland, garlanded in the coils left by tube worms, resembles a tribute to Poseidon, or a Medusa of the depths. And if this is eerie, what about the bent, blue iron road-sign to “Craco,” which Mike Nelson bought in a South London market for five pounds? It turned out to be from a once thriving medieval hill top town in Basilicata, in the south of Italy, now abandoned after an earthquake. “What I had acquired,” Nelson writes, “was in fact a sign to a ghost town.”

Nelson did at least find out where his sign came from. Others gave up, content with the mystery. After her mother died Marina Warner discovered a heavy, golden, grooved sperm-whale tooth “mixed up with some old coins, regimental buttons and buckles, race meeting tags and a very worn, initialled cigarette case.” In Fiji these tabua, the teeth of the “wonderful giant of the sea,” are cult objects, medals, honored tokens of exchange. But how had it come here? Was it perhaps a gift to her grandfather, who played cricket around the world? She has no idea.

The tooth made me see how we are surrounded by the flotsam of former lives, close and far. It’s curious, too, how the show makes the objects themselves appear to take on life, as if some “lost” things preserve themselves carefully and then actively decide to reappear. In 1962 Michael Craig-Martin shot a film on the Atlantic coast of Connemara, where empty windows in abandoned crofts open on mist and distance. The result, FILM, was his BA thesis at Yale, but the single copy disappeared. “Then, in 2000, my daughter found it in the bottom of an old family trunk, perfectly preserved in its round grey tin.” It is the only film he has ever made.

Everything has a tale, making the exhibition feel like a volume of visual short-stories. These can tug the heart-strings, but can also make you laugh. Miranda Pennell’s find is a page from a 1936 letter—written by a young petroleum geologist in Iran to his mother—with a gleefully scary sketch: “Picture of Centipede I killed in the bathroom. Life size!!” David Shrigley’s shows a photo of a note pinned to a tree, all in capital letters, “LOST. GREY-WHITE PIDGEON WITH BLACK BITS. NORMAL SIZE. A BIT MANGY LOOKING. … DOES NOT HAVE A NAME.” I’ve definitely seen this bird.

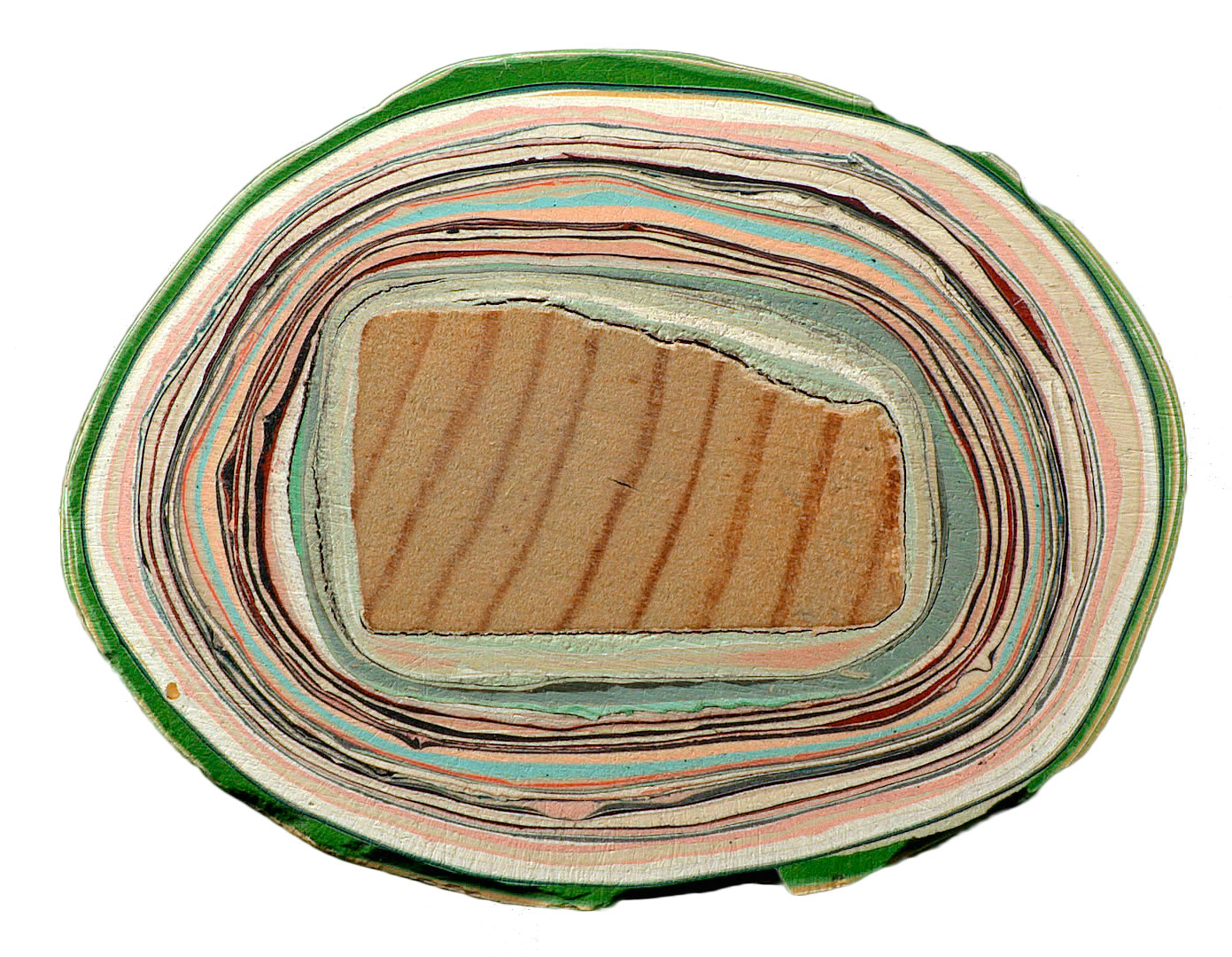

Throughout, there is great tenderness and a frequent mention of parents, grandparents, children, and often the backstory is less about the objects than their part in the life of the finder, like Gillian Wearing’s blurry, cheerful teenage photos, “images that show me finding myself.” Thomas Heatherwick, for example, offers the silver-plated spoons that his grandmother used to make gravy, their ends shaped by seventy years of scraping round the pan. But perhaps my favorite of these family images is John Smith’s Dad’s Stick. Smith’s perfectionist DIY father painted every room in their house over many years, changing colors by decade. He always stirred the paint with the same stick and before he died he cut off the end—and there revealed is the whole history, multi-colored rings of a life-tree, beautiful and strange.

If my account sounds like a list, believe me there are many more objects, and many more distinguished artists: in an alphabetical spin you could find Phyllida Barlow, Richard Deacon, Tacita Dean, Jeremy Deller, Edmund de Waal, Mona Hatoum, Michael Landy, John and Roberta Smith, Rachel Whiteread—and more. Almost every piece is resonant and surprising. I thought I knew Anthony Gormley, for example, had him safely pigeonholed, until I saw his Iron Baby. Taken from a cast made of his six-day-old daughter twenty-nine years ago, the baby turns her back on us, curled up not on her mother’s breast but alone on a bare wooden floor – a reminder of all the abandoned babies who entered these doors, a tragedy of separation.

Advertisement

Found is a show of memory, of time, of attachment and fracture, of loss and retrieval. And perhaps all who see it will find something of themselves. On a personal note, I’ve known the Foundling Hospital since I wrote on Hogarth years ago, and when I visit I always nod to his foot-tapping portrait of the white-haired Captain Coram (the foundling children used to think this was Father Christmas). But this time, in the corner of a corridor, I bumped into an unspectacular black long-case clock. It was made by John Whitehurst, a clock-maker and geologist and a member of the eighteenth-century Lunar Society, another subject central to my past work. I’ve been to the Foundlings so often, and never seen it. Yet here it is, solid and plain, simply saying “Found.”

“FOUND” is on view at the Foundling Museum through September 4.