Like a teenager admiring his reflection before a big night out, the Renaissance accountant Matthäus Schwarz often took note of the outfits in which he looked particularly fine. As a child, he had been fascinated by fashion and would ask old people about what they had worn thirty or forty or fifty years earlier. In 1520, at age twenty-three, he hired an artist to draw his most notable getups and collected these in a book that he continued to fill throughout the rest of his life.

Schwarz’s outfits, and those of his son Veit Konrad Schwarz (who derided his father’s “fanciful” sensibility before undertaking almost the same project), are reproduced in The First Book of Fashion, edited by Ulinka Rublack and Maria Hayward. The first thing one notices are the fabrics: white fustian, a heavy cotton and linen cloth, covered with strips of bright yellow and pale grey silk; scarlet hose slashed to reveal green taffeta. Augsburg, where the Schwarzes lived, derived much of its wealth from cloth production, and the fabrics are drawn with particular care, highlighting the softness of fur or the shine of silk.

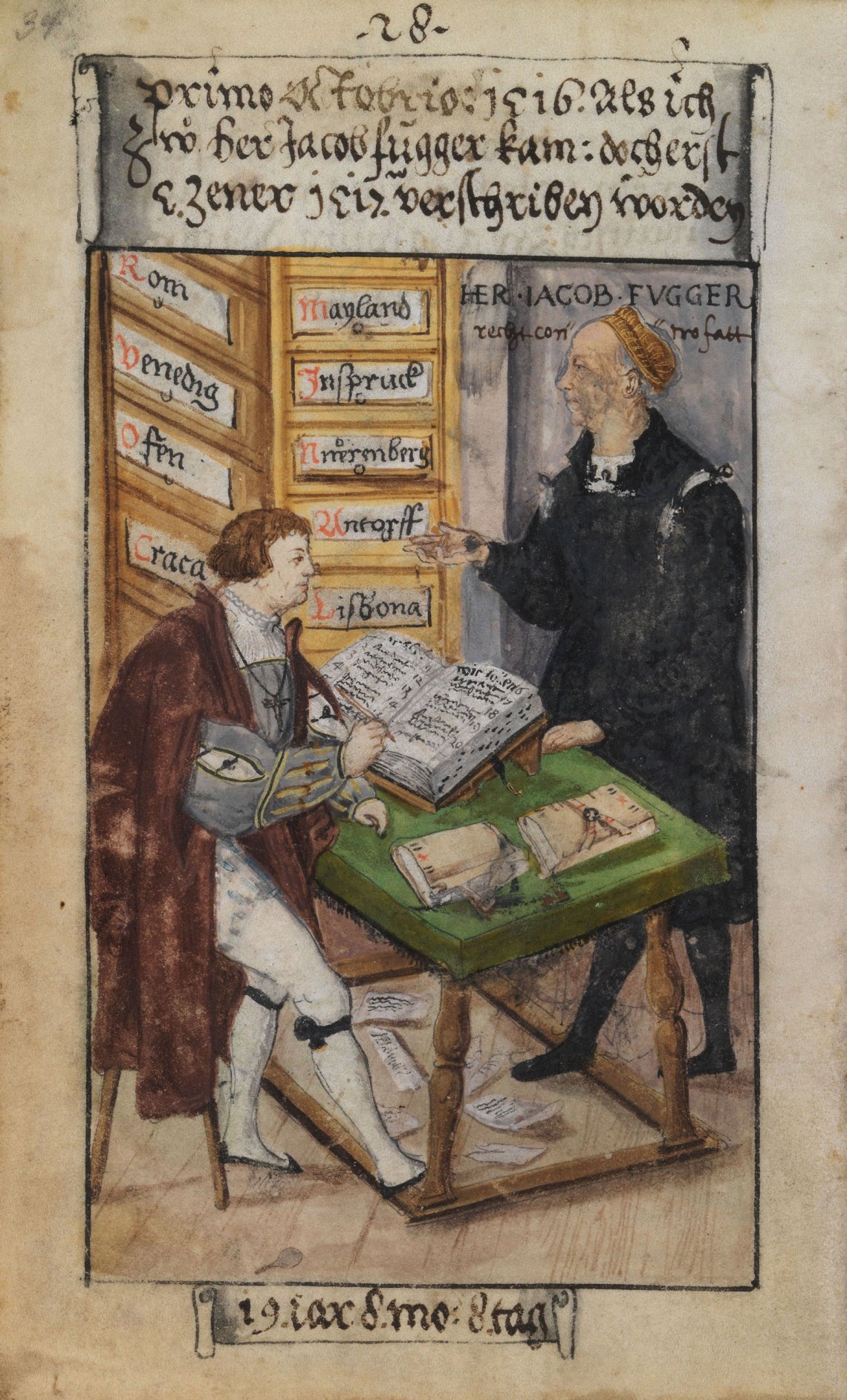

The editors make much of Schwarz’s social aspirations. A bookkeeper for the influential merchant Jakob Fugger, creditor to the Habsburgs and one of the wealthiest men in history, Schwarz spent his career attempting to better his position through his connection to Fugger’s family. Sumptuary laws in much of Germany dictated clothing style based on rank. A 1530 Imperial Ordinance, for example, forbad merchants from wearing velvet, damask, or silk satin. For Schwarz, in more permissive Augsburg, the rules concerning rank and fashion were less rigid. A page of his book shows him writing accounts in Fugger’s office. Fugger wears a long, black, woolen gown, with a dull yellow cap, while Schwarz sits almost suggestively, his brown gown open to reveal a blue doublet underneath, finely tailored with knots and slashes.

Just as often, he dresses to impress the Habsburgs, hoping that they would ennoble him for his flamboyant look. An image of Schwarz at the Imperial Diet in 1530 shows him in a doublet striped with yellow damask and red silk satin. (King Ferdinand favored yellow for joyful occasions.) The strategy worked. In 1541, the son of a wine merchant received a certificate of nobility. He immediately had himself painted in an expensive fur coat.

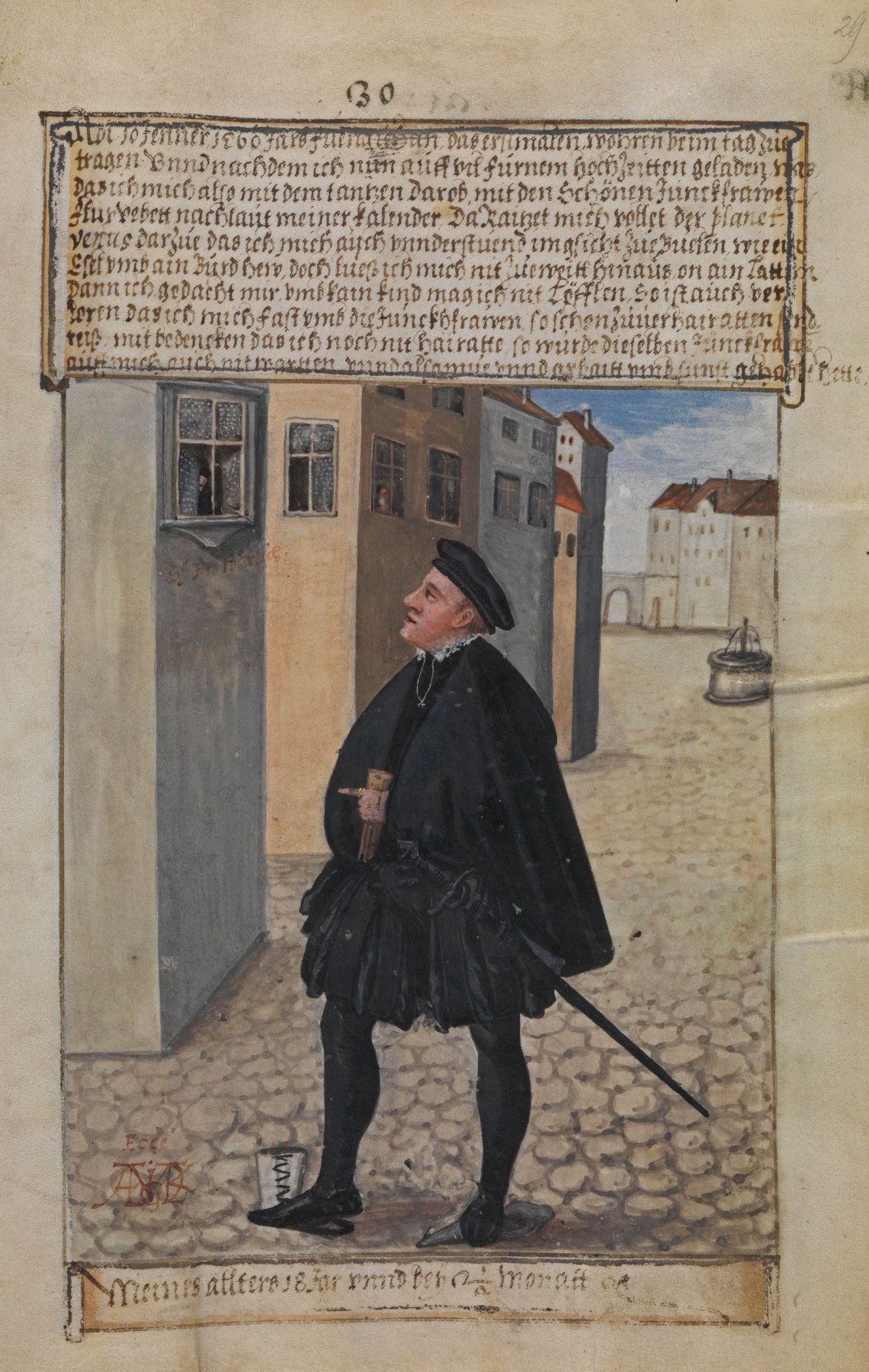

Dressing for seduction seems to have been Veit Konrad’s central concern; he pairs pictures of his outfits with laments about his failure to find a suitable wife. One portrait has Veit standing in a full black cape in an empty Augsburg street. He looks wistfully at a woman hiding behind a shutter in a window above. The caption describes his woes: “The planet Venus fully tempted me to also flirt face-to-face, like a donkey [goes after] a bundle of hay.”

Advertisement

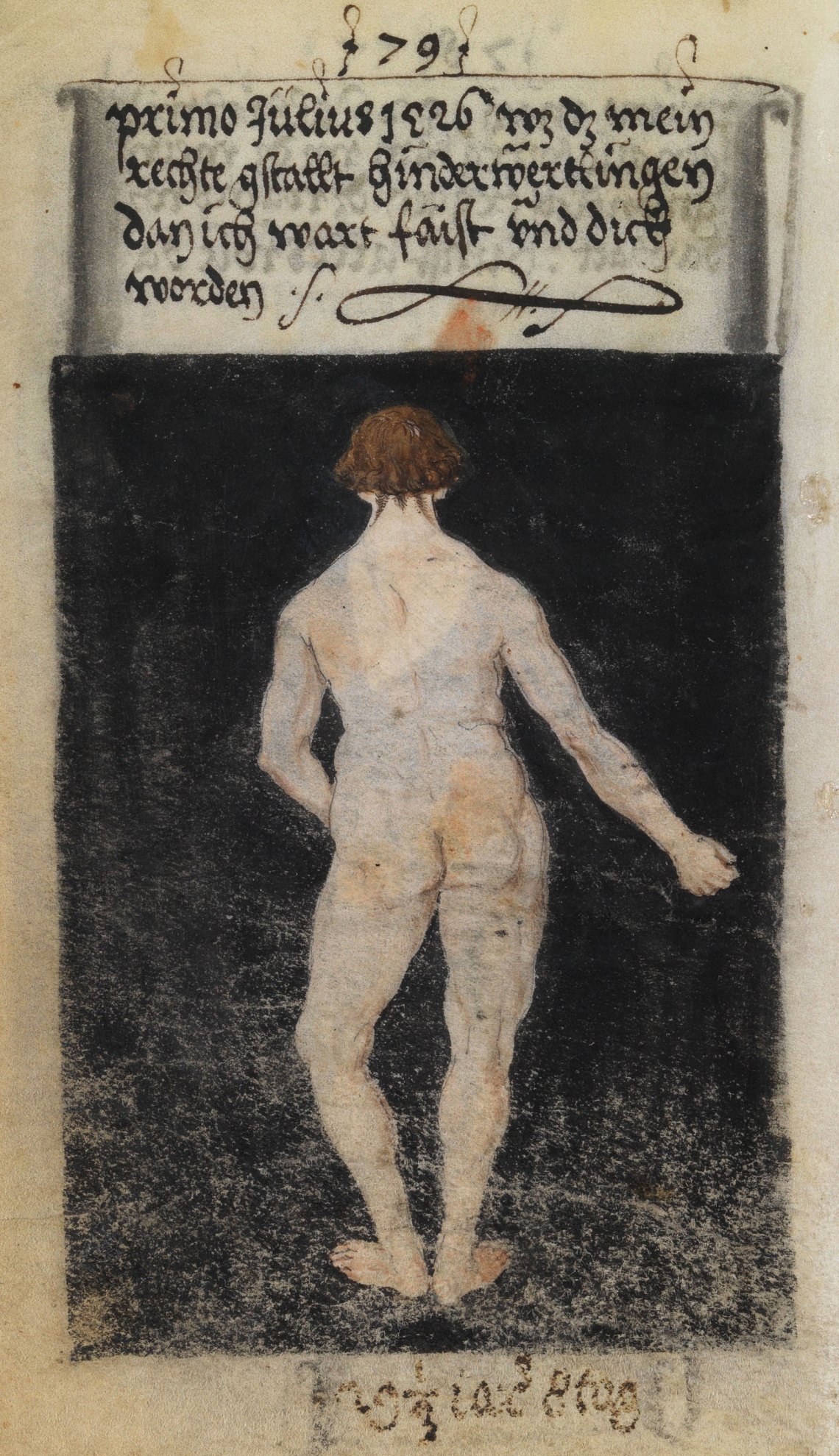

Men’s clothing today tends to promote a unified, square silhouette—think of the suit, with its simple, masculine shape and formal integrity. By contrast, many of Matthäus’s clothes highlight what would today be seen as feminine characteristics. The bright hose give him long and slender legs, while the tapered doublet accentuates a small waist. In his colorful jackets, the shoulders don’t seem broad so much as puffed up like a rooster’s chest. When, at twenty-nine, he began to be “fat and round,” by his own admission, Schwarz’s clothing seems to get looser and fuller. He portrays himself more frequently draped in coats and gowns, often in more subdued colors.

The editors’ commentary notes that Schwarz documented some of the earliest known sportswear. One image shows him learning to fence in motley silk satin. But looking through the images, it’s hard to imagine actually moving in these clothes. The open shoe Schwarz favored forced a slow and careful step. Hose had to be held up with garters, or else they would fall and wrinkle. One particularly excessive doublet had 4,800 slashes with velvet rolls, all in white. What could you do in these clothes except pose for a picture?

At the end of the book, the authors present Schwarz’s yellow and red king-pleasing outfit, reconstructed on a model. One of the hardest parts of the reconstruction, the authors note, was making sure the hat wouldn’t fall off the model. In the end, “it stayed in place as long as he retained an upright posture and moved his head in a self-aware manner.”

The First Book of Fashion, edited by Ulinka Rublack and Maria Hayward, is published by Bloomsbury.