Historians are going to have a hard time with this election, featuring as it does two candidates each of whom presents unprecedented and unique qualities: the first woman presidential nominee in a society that hasn’t yet quite come to terms with the idea of a female president or even candidate, and a businessman out of reality television who knows next to nothing about governing or government policies and plays on America’s dark side.

But while Donald Trump has garnered most of the attention—we keep wondering what outlandish thing he’ll say next—the story of Hillary Clinton may well in the long run be the more interesting. It’s certainly the more poignant. She’s worked so hard and so long to be the first woman elected president. She’s by far the more prepared, the smarter, the harder worker, yet she’s hit so many headwinds that, though she’s still favored to win, the election is more in doubt than it was on Labor Day.

The virtual tie in several national polls means little at this point, though of course each side would prefer to have a sizable lead. National elections have usually been very close. The most relevant fact is that Trump still has the harder path to the required 270 electoral votes. But now, as of mid-September, Trump has been gaining over Clinton in some crucial “battleground” states; and some states that only recently seemed to be safely in Clinton’s column may be slipping away. In time, we will learn the extent to which this tightening of the polls was affected by Clinton’s having fallen ill at the ceremony honoring the fifteenth anniversary of 9/11, and the furor in the press over how her illness was handled. Several of the new polls were taken over the three days of September 10-12.

The release this week of two polls showing Trump leading Clinton by five points in the critical state of Ohio—Trump cannot win without it—was the kind of startling information that can change the psychology of a race. Clinton had led in Ohio in August and up to Labor Day. Trump has also just pulled ahead in other important states: Florida, Nevada, and Iowa (by a lot). Within the space of less than two weeks the political talk switched from Clinton having a possibly unbreakable grip on the Electoral College vote to how much Trump has gained on her and how much Clinton has slipped. How did this happen? Why isn’t the far more qualified candidate creaming an opponent so clearly unfit for presidency? What is it about Clinton that puts so many people off?

Of course a great deal of it has to do with her political behavior—her weakness as a campaigner, particularly in the early months; she improved considerably over time—and, obviously, with her lies about the private email server. But the historians may miss what should be inescapable: though many of Clinton’s problems are, as it’s said monotonously, self-inflicted, some have to do less with what she’s done than with what she is: Hillary Clinton is the unusually bright woman who turns off a lot of men—and some women, too. She’s the smartest girl in the class who does her homework more fastidiously than the others and turns in her papers before they’re due.

Anyone who didn’t see the latent sexism in the way that Matt Lauer treated Clinton in the NBC forum on September 7—an event featuring both candidates supposedly talking about national security though Lauer insisted on grilling Clinton about the server—has to have had blinders on. Lauer didn’t tell Trump to hurry up with his answers the way he frequently did Clinton; he was patronizing to her, an attitude that can befall women out in the world.

In describing Clinton as lacking the stamina to be president, Trump, who goes home almost every night, is conveying that the presidency is a man’s job. A man who marries two models and one starlet and who has a bullying nature can be quite thrown off by a brilliant, strong woman. Clinton’s strong voice, though lately she’s tried to reduce the yelling—the charges of a double standard on this are valid—can be off-putting to women as well as men. How many male candidates are urged to smile more?

There’s no question that Clinton has shown her less attractive traits in this campaign, and her displays of her lighter, playful side, which she definitely has, have gone largely ignored. Though Clinton has a cold aspect, her considerable warmth when she turns it on has been more on display of late, though it’s essentially ignored in the descriptions of her. (There’s a reason that so many people, especially women, who have worked for Clinton remain devoted to her.) I think there’s been an overreaction to her more graspy and evasive side—a lack of proportion on the part of many Democratic and Independent voters. Anecdotally one hears it time and again from them: “I just can’t vote for Hillary.” If questioned, this leads to statements of disgust with the way she handled the private email server and some vague sense that there’s been corruption in the dealings of the Clinton Foundation. In fact, while there’ve been all sorts of insinuation on the part of Republicans and career opponents of the Clintons and some suggestive news reports, as of now, no actual corruption in the foundation’s dealings with Hillary Clinton’s State Department have been unearthed.

Advertisement

The case of the Trump Foundation is the opposite. While until very recently it received less attention in the press, The Washington Post has disclosed that it has functioned as a sort of slush fund by which Trump solicits funds from others—Trump himself hasn’t made a personal contribution to it since 2008—and then he makes donations of other people’s money to various causes, taking bows for his generosity. Some of the foundation’s funds have been used for Trump’s own gratification, such as purchasing a football helmet signed by Tim Tebow and one of Tebow’s football jerseys (for $12,000); Trump also signed a check from the foundation’s books for $20,000 for a six-foot portrait of himself—the use of foundation funds for gifts to oneself is illegal. Trump has had to pay a fine for making a political contribution of $25,000 with foundation funds, which is illegal—apparently to head off a Florida attorney general’s investigation of Trump University. Now an investigation into the foundation has been opened by New York state’s attorney general. (Trump has complained that the New York AG is a partisan Democrat, but there’s nothing partisan about the question of whether a foundation violated the law.)

Those Democrats who say they simply cannot vote for Clinton—some are planning to waste their votes on third party candidates, who take more votes from Clinton than Trump—apparently haven’t thought through where this leads: helping Trump. This lack of concern for consequences is reminiscent of those Democrats, mainly on the left, who said that they were “disappointed” in Obama– and didn’t turn out to vote in midterm elections. This contributed to the steep Democratic losses in Congress in 2010 and 2014.

Whether the tightening of the polls constitutes a trend won’t be known for some more weeks. But meanwhile the numbers have made for useful propaganda for Trump who excels at blaring victorious notes, using the fact that he’s winning as an argument for falling in behind him. Trump is also expert in diverting press attention from less positive news about him. On Wednesday, September 14, Newsweek published an expose about how Trump’s business organization “has spread a secretive financial web across the world,” and has “deep ties to global financiers, foreign politicians and even criminals,” all of which would create serious conflicts of interest if Trump were to be elected president. On the day of the Newsweek report Trump suddenly let it be known that, in the taping of a television show to run the next day, hosted by the aptly named Dr. Oz, he’d disclosed the results of new medical tests he’d recently undergone; supposedly unlike Clinton (who in fact had already disclosed far more about her health history than Trump had about his), Trump could claim he was being “transparent” about his health records. His new medical tests, which still left out a great deal of information, were conducted by the same doctor who had written the one-page laughable report late last year that said that Trump would be the healthiest president in history.

The press’s fury at Clinton, after she left the lengthy fifteenth-anniversary commemoration of 9/11 early last Sunday, had in some part been stoked by her long period of being inaccessible to them. This had started to change—Clinton had recently begun chatting with her press corps daily—but resentment toward her secretive nature, including about the server, hadn’t died. The press was quite agitated that she’d kept the diagnosis that she had pneumonia secret for two days, and that for nearly two hours on Sunday afternoon her whereabouts were unknown to them. It was sheer chance that a bystander caught on his cell phone her near collapse as she entered her van. The entire episode played into the theme that Clinton is too evasive.

Actually, it’s hardly shocking that she attempted to keep the diagnosis of pneumonia under wraps and to push through it. Candidates and even presidents also shake the press from time to time—Trump did so on Thursday night. Clinton is far from the first sick presidential candidate and she wasn’t unique in trying to carry on. A presidential campaign is open-ended and insanely intense, and candidates generally go to great lengths to avoid canceling an event. Each one is an opportunity to win votes, and candidates push themselves until they run out of time. Trump, who hadn’t come close to scheduling as many events as Clinton did, may be an exception but he’s picking up his pace, and there are enough weeks left until November 8 for him to get exhausted.

Advertisement

Clinton’s time out—she missed four days while she rested up—was costly to her in one important way: she’d focused her campaign on attacking Trump and had yet to make a case to the voters why she should be elected president. She had proposed a welter of programs to improve the lives of most Americans and while as yet it lacked a coherent vision or theme there was a positive case to be made. In fact she was to begin to make it this past week when she fell ill. But she still has some time. Meanwhile, while she recuperated she had powerful surrogates in President Obama and her husband (who filled in for her on a fundraising trip to California and Nevada). Barack Obama campaigned for her in Philadelphia and was clearly joyful at returning to the kind of campaigning he does well: funny, incisive, and having a good time interacting with the crowd. In Philadelphia Obama did a long rap expressing his wonderment that working people would think that Donald Trump was their friend. The crowd loved it, and him. While many observers believe that a recent poll placing Obama’s approval rating at 58 percent is on the high side, almost every poll puts his standing at above fifty, a good place for a president nearing the end of his second-term and a useful one for Clinton.

Of further possible help to Clinton was this week’s unexpected good economic news: a strong rise in most Americans’ wages in 2015 over the previous year, including among the poor and lower-wage workers. This helped the president argue that his administration not only had staved off the deepest recession since the Great Depression but also that standards of living have generally improved—when the opposing candidate was campaigning on the theme that times are terrible, that America isn’t “great.” It might help Clinton because it gives her more of a rationale for asking the voters to think twice in an election that’s supposedly about change. “Change” is a fuzzy term suggesting nothing in particular but simply a desire for something different. The theme lacks analysis of what’s wrong and who caused it—for example in the case of the stalemate on Capitol Hill, which is the direct result of an opposition party determined to deny the president any legislative successes.

But Clinton is having trouble assembling the coalition that twice elected Obama; she’s especially coming up short with young and Hispanic voters—even in the face of Trump’s running insults toward the latter group. That Clinton would have an enthusiasm problem has been foreseeable for a long time; she’s simply not a magnetic campaigner. A great deal will ride on whether the elaborate turnout operation the Clinton campaign has built is effective enough. Trump has nothing to match it and is dependent on the efforts of the Republican National Committee. But a victory produced by the dull mechanics of getting out the vote as opposed to being propelled by excitement doesn’t give a new president the needed boost to push an agenda through Congress.

Clinton’s propensity for less than deft campaigning was displayed in her off-the-cuff comment at a fundraiser on Friday September 9 (though she’d said something like it before) that she could put half of Trump’s supporters “into what I call the basket of deplorables.” She listed what she sees as traits of Trump supporters: “racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamaphobic.” Her expression of regret the following day that she’d cited such a high proportion of “deplorables” didn’t get her out of trouble. Trump and other Republicans pounced on her comment with ill-disguised glee.

It’s not that what Clinton had said was so outrageous: the writer Ta-Nehisi Coates among others argued that she was correct in her estimation of the proportion of Trump’s followers who held the views she cited. But there’s a political code that a candidate mustn’t impugn a rival’s followers. Anyway, it’s not a good idea because it allows the rival candidate to express shock and horror at an insult to good, hard-working Americans. In other words, it’s an excellent resource for faux outrage and a useful organizing tool to get one’s supposedly maligned supporters to vote. Similarly, Barack Obama wasn’t wrong in 2008 when he observed that people down on their luck in hard-hit areas “cling to their guns and religion.” But that word “cling” gave the Republicans ammunition for picturing Obama as an elitist out of touch with real people.

Clinton’s inartful comment was followed two days later by the unfortunate cell phone clip of her nearly collapsing—which played on television probably a million times and came on top of Republican insinuations, stoked by Matt Drudge, that she was ill with some mysterious malady (this wasn’t the first picture of her falling). This made for a bad few days for Clinton. But when on Thursday she emerged from her rest at her home in Chappaqua, New York, Clinton looked fine and there was nary a cough. She said that the time off the trail had probably done her some good, gave her time to reflect on the campaign in a way that’s not possible while going full speed on the road. On her first day back, she spoke in North Carolina—her aides said she would now focus on the battleground states—and then addressed the Congressional Hispanic Caucus’s annual dinner in Washington.

Clinton’s speech to the Hispanic organization was the best I’ve seen her give—this includes her convention speech. Her voice under control, she modulated according to what she was saying, and she spoke effectively of the contributions Hispanic citizens had made to this country—and she knew a number of their leaders. This was a far cry from Trump’s clumsy if not insulting speeches aimed at, but almost never given to, minorities about the terrible lives they led. (“So, what the hell do you have to lose?”) Clinton cited things she wanted to do upon taking office: “create an economy that works for everyone, not just those at the top by making the biggest investment in new jobs since World War II,” including on new infrastructure projects; institute paid family leave (a more generous program than the one Trump announced earlier in the week since his only included mothers and would last half as long and would be aimed at those who earned enough to take tax deductions to pay for it). In her first hundred days, she said, she would send to Congress a proposal for “comprehensive immigration reform,” including a path to citizenship—again, a sharp contrast with what Trump had proposed. She even suggested that she would end the raids and roundups of illegal immigrants that Obama had ordered. The audience loved it; Clinton was on target now, speaking from her strengths.

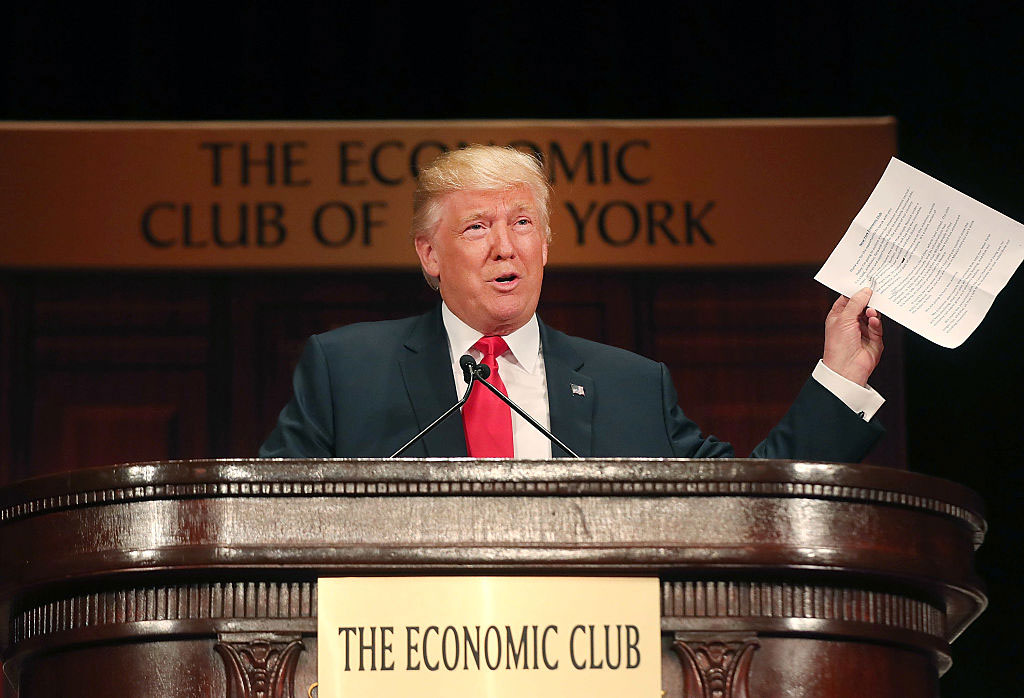

Donald Trump has begun to show the kind of discipline as a candidate that his previous advisers had despaired of seeing. On Thursday morning, an essentially contained Trump delivered a serious speech—his second policy speech—to the prestigious New York Economic Club. His sweeping plan is economically shaky to say the least, assuming as it does that $4.4 trillion in tax cuts would only cost the government $2.6 trillion (via the widely discredited “dynamic scoring” that assumes economic growth will ensue from the tax cuts); he pledged 4 percent economic growth, a number he must have plucked from the sky; and he threw in some Jack Kempian vows—now adopted by Paul Ryan—to create jobs in depressed neighborhoods. Trump vowed to slash corporate taxes (to the delight of the people in the room), and lift regulations on energy production plants. He’d also reopen coal mines—in Trump’s view there’s no climate crisis.

The thing about this speech, though, was that Trump looked and sounded normal, like a regular conservative Republican. So much less is expected of Trump that when he delivers a speech on the teleprompter with some smoothness, as he now can, it’s considered a major achievement. When he sticks to the script and doesn’t wander off into comments that get him in trouble he’s a statesman. In the middle of this week, though, Trump burst out of his unusual restraint about Clinton’s illness—yielding to temptation to take a couple of digs at her being sick.

Actually, within the past couple of weeks we’ve seen the reckless Trump say (in the NBC forum) that when the Iranians “in their little boats”—he’s good at imagery—make rude gestures to the US navy “in their beautiful ships” he’d “blow them out of the water”—that is, he’d go to war with Iran, with all the dangerous possible consequences, over a gesture. That same Trump violated the solemn agreement that presidential candidates make when they get super-secret national security briefings that they’ll reveal nothing. I understand the point of wanting an informed president-elect (a policy encouraged by Harry Truman), but why not start the briefings right after the election?

We also saw the Trump who is uncomfortable with minority audiences and blundered his way through a trip to Flint, Michigan, where the pastor of a black church interrupted him as he got full flight about Hillary Clinton’s evils to tell him he hadn’t been invited into her church to make a political speech. Trump meekly complied but, typically, when he’s been embarrassed or attacked, the next morning he lied to Fox News that the woman had been a nervous wreck and that he knew that she had planned to embarrass him. (Hillary Clinton used this example of Trump’s mean-spiritedness—when he wasn’t in the pastor’s presence—in her speech in North Carolina.)

While political commentators watched this week’s churn in the polls, many were already discounting much that had happened. The decisive event, they said, would be the first presidential debate on September 26; there would be two more debates but these commentators deemed the first the determining one. This is what’s wrong with the part that debates have come to play in our presidential elections. A one-off event shouldn’t begin to displace the weeks and months of the candidates’ efforts in the campaign. Worse, the qualities that are rewarded in a debate have virtually nothing to do with what’s required to run the government: the sharp one-liner in particular. What does that have to do with solving the great problems the country faces, with dealing with Congress and with foreign leaders? What was the significance of one of the most famous lines of past debates: “There you go again,” (Ronald Reagan to Jimmy Carter)?

Then there’s the press’s obsession with determining who “won.” I’ve participated in two debates and it never occurred to me that someone had won them: to name a winner is to make a subjective judgment based on…well, on what? The one-liner or the greater command of the issues? And what does “winning” a debate mean? The debates don’t reward depth of thought or understanding of issues. There’s no time for that. It appears that this year’s debates are being set up by the press to distort the election to a greater degree than ever.

It would be nice to be able to assume that the election will be decided on the respective qualifications of the contenders for the job. But given the extraordinary weight placed on the debates by the press, the unclear thinking on the part of so many would-be voters, and the frustrating search for an elusive satisfaction with the choices, that just might be too much to hope for.

Part of Elizabeth Drew’s continuing series on the 2016 election.