Soft City is something of a miracle. Not only for existing in the first place, but for surviving at all. Drawn between 1969 and 1975 by the Norwegian artist Hariton Pushwagner (now often just Pushwagner, though born Terje Brofos in 1940), it languished in obscurity for decades and was very nearly lost before finally being issued in book form by the Norwegian publishers No Comprendo in 2008, following a messy legal dispute involving the artist and his former dealer. Most pointedly, however, it is a miracle of its native medium—the comic strip—for its startling and disquieting vision in a form that had never before quite seen anything like it. Funny, or maybe not so funny, that it would take forty years for the rest of the world to realize it.

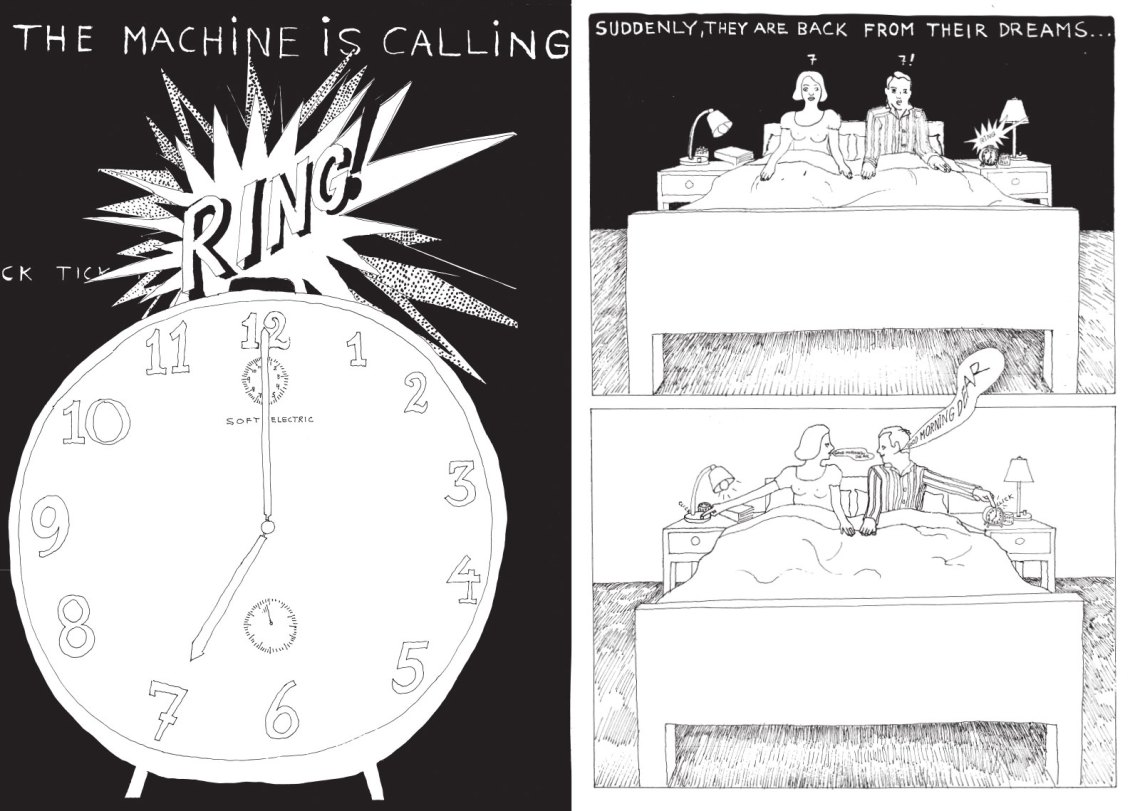

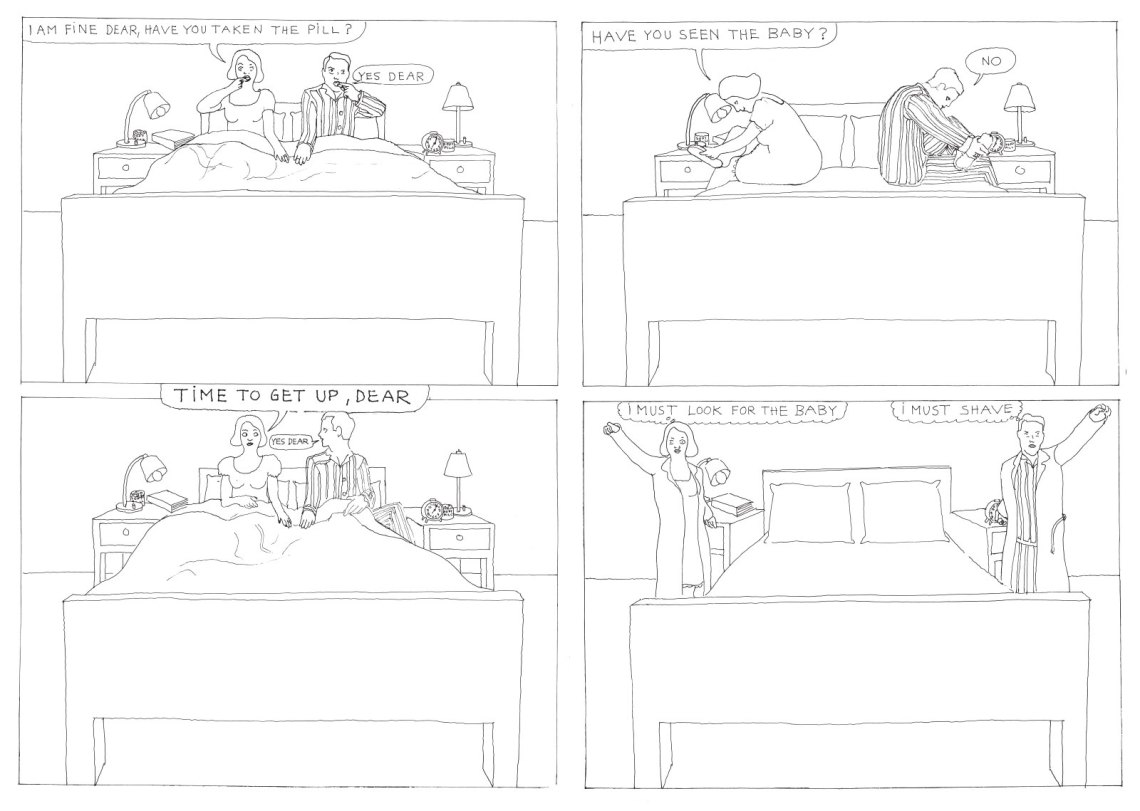

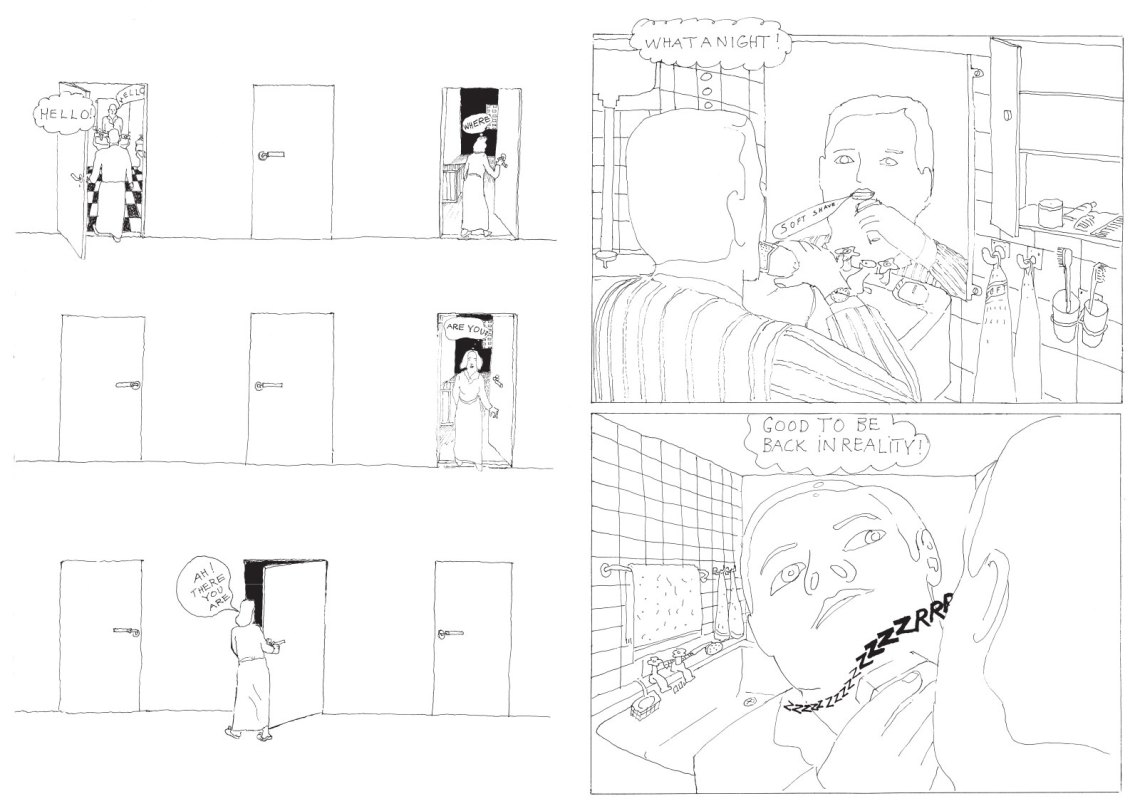

Its simple “plot,” one day in the life of one of a thousand families in an impersonal, oppressive, seemingly futuristic military-industrialized complex/city, has its precedents—Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World readily come to mind—but Pushwagner’s comic-strip dream book is unlike anything ever drawn, the sort of magical object one wakes up from seeing in the imagination only to fade within seconds of consciousness. Maybe it’s not surprising that it all begins with an awakening: a cinematic, reader-encompassing view of a sunrise over an impersonal wall of windows that looks more like a computer punchcard than habitable buildings, the reader “moving” in toward these windows to the close-up face of an infant behind the bars of a crib, a sunrise narratively conflated with the eyes of the baby, all of which inverts to reveal itself as the perceptions of the child within the crib. This is no ordinary comic strip, especially for 1969. 1969!

Though it masquerades as a narrative, the term “graphic novel” seems inadequate to describe Soft City, especially for a book that existed before the term was even coined. It ends up where it starts, with the face of the baby—now in darkness and crying at the moon and, one assumes, at some vague inference of the fearful repetition and spiritual deadness of his existence.

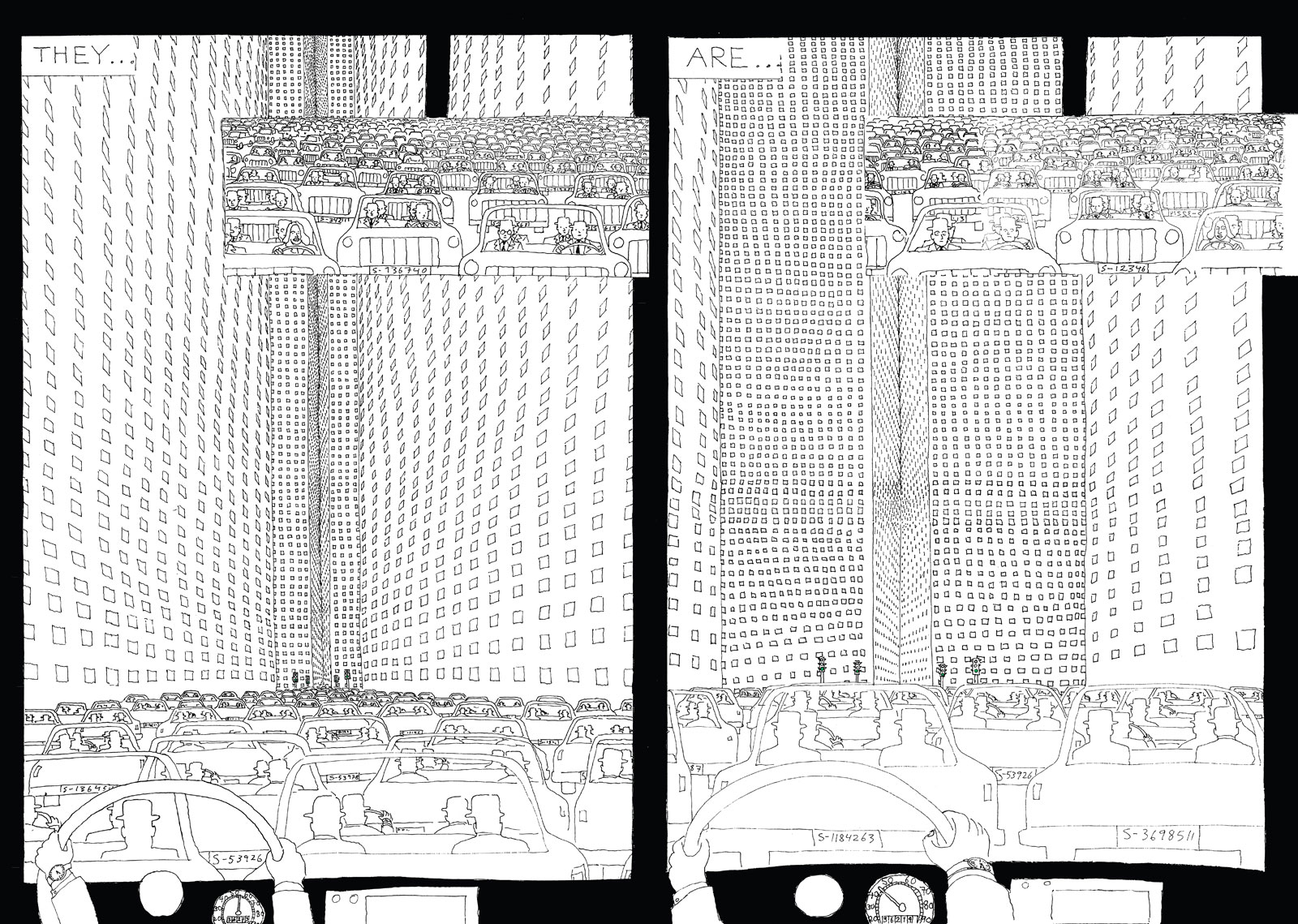

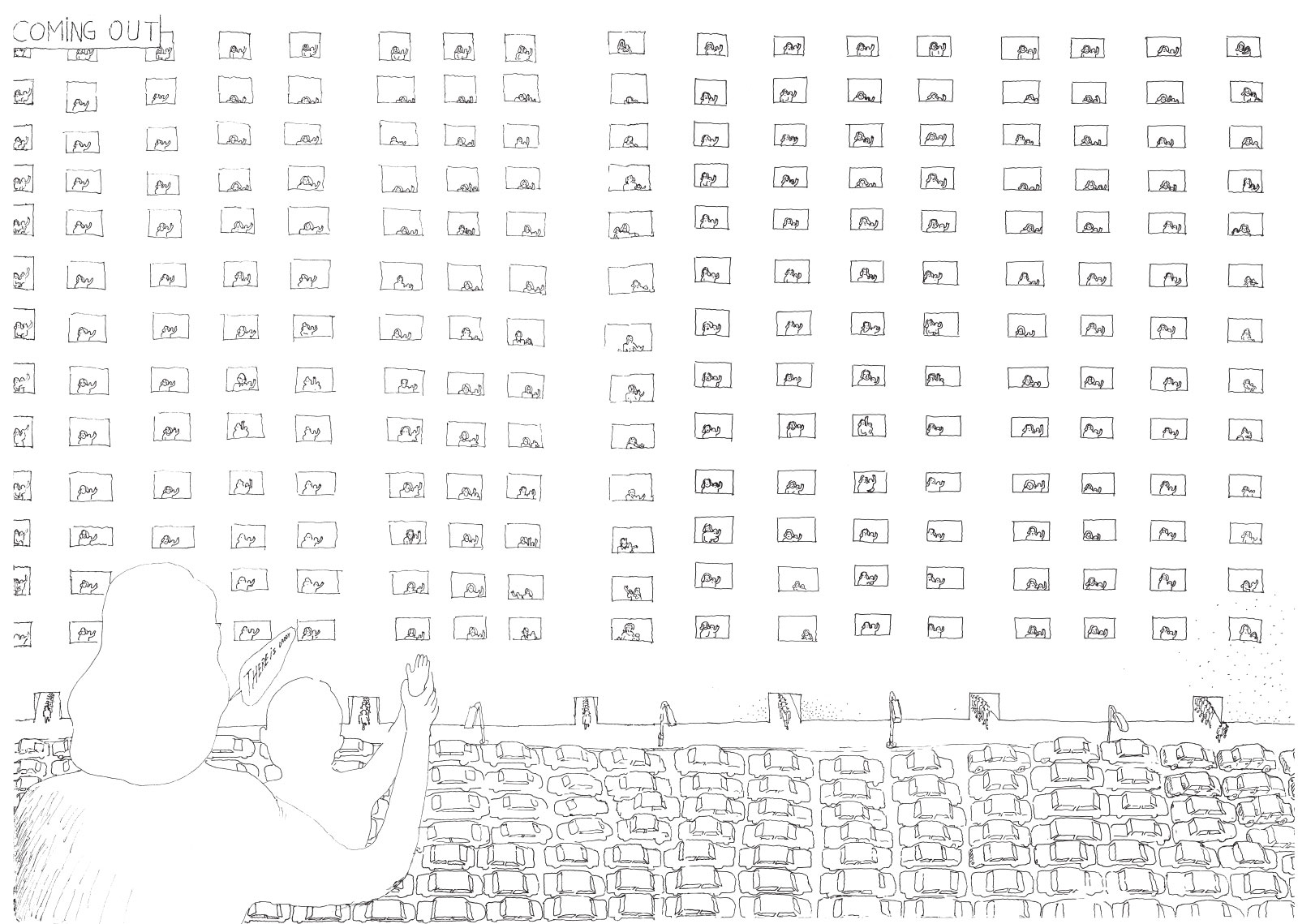

Never taking the easy route out, Pushwagner surprises the reader at nearly every page turn, shifting narrative allegiances and avoiding mundane visual replication in these astonishing crowd scenes, where, if the reader looks carefully, individuals and personality quirks still survive despite the airless, inclined landscape of regulated humanity they inhabit.

His shaky ink line and quirky collaging of news clippings onto the original drawing also remind the reader-viewer that this is the work of an artist, not a craftsman covering his tracks with slick commercial tricks. The whole seems drawn entirely from the need to realize a consuming vision, a writer ruminating (“Where is the mind when the body is here?”) while his artist half looks on in horror. That both halves operate so well makes it a surprising, and lasting, work of art.

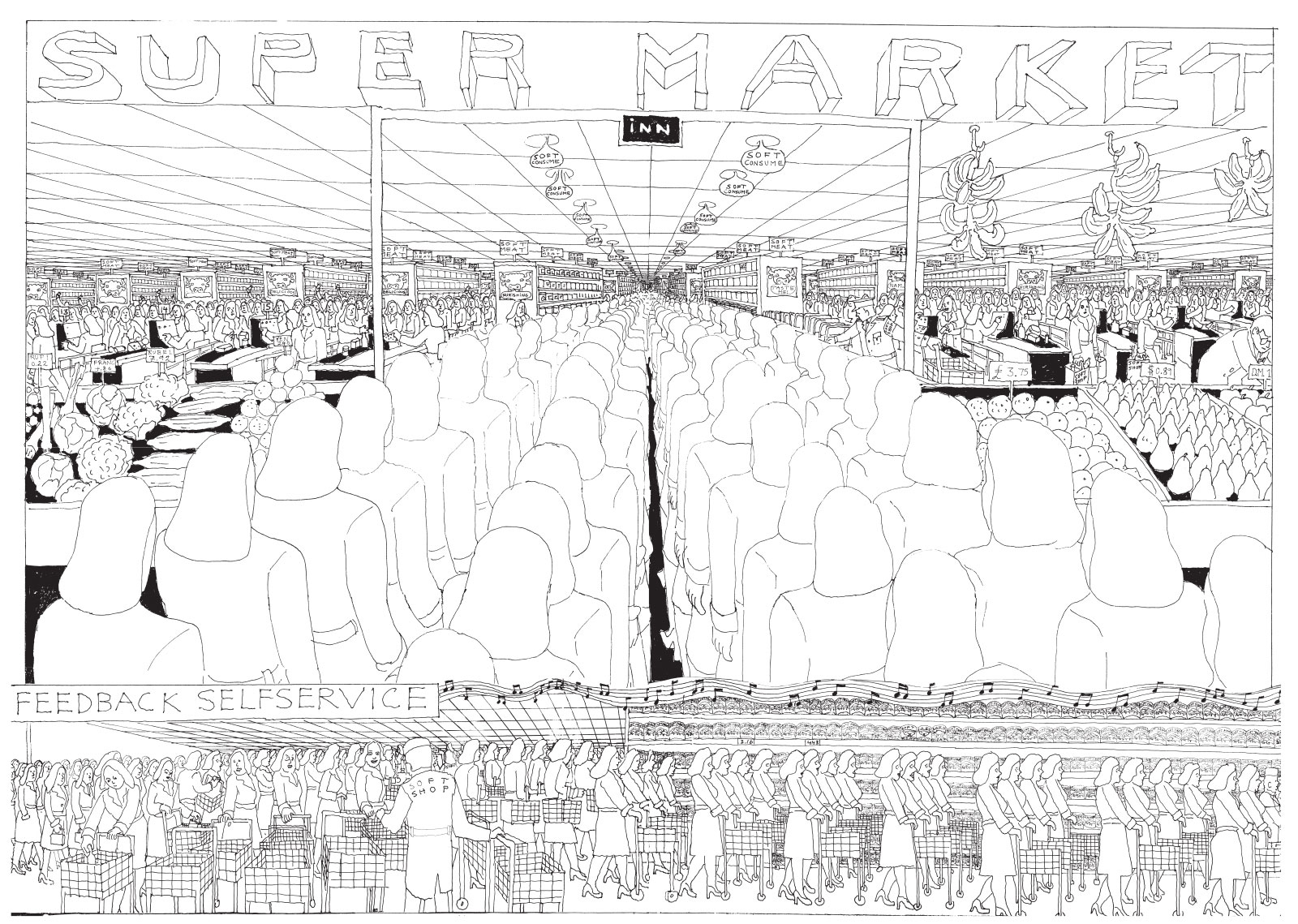

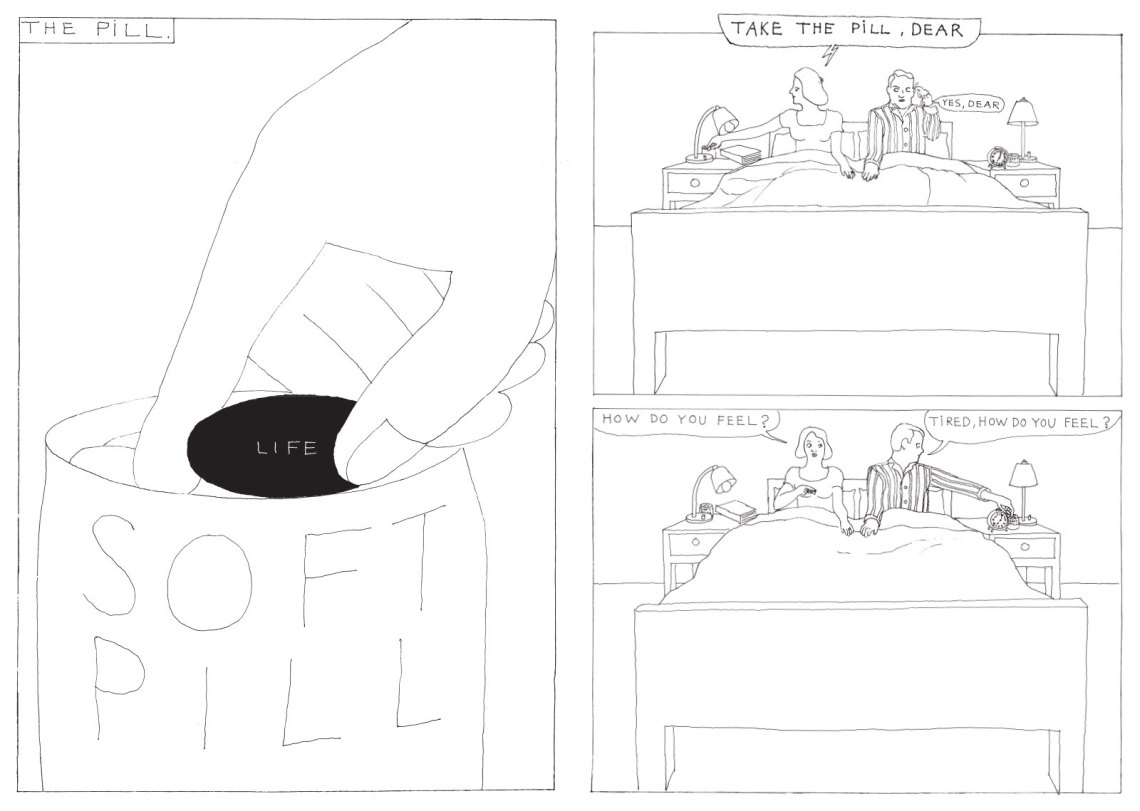

Shifting between the designated sex roles of the male and female preparing for, and then embarking on, their respective days out of the cells of their apartment beehive—the males marching off to work to dominate the planet, the women dropping their children at child care then shopping in endless receding spaces of consumption—the reader is left with no real person with whom to identify, no memories or “character” with which to empathize. The overall tone is best described as alien, veering between distant observation and close consciousness, the semi-poetic thoughts of its people like advertising slogans or self-satisfied sensations, infantile in their puerile comfort-revelation and intellectual simplicity: a mother uttering Joycean phrases such as “sweet radio grand prix” and the child thinking “how strange the world seems.” The seemingly endless vistas of commercialism ultimately result in a crushing dehumanization. In this, Pushwagner was not only narratively but also culturally prescient; one has to keep in mind that at the time this book was drawn, the supermarket was still a relatively humdrum neighborhood affair, nothing like the gaping, hungry superstores that swallow consumers in Soft City and in our own suburbs today. (The book could just as easily be retitled Costco, though that would lack a certain mellifluousness.)

Along these lines, the peculiar congruency of Pushwagner’s repeated use of the word “soft” with the current near-ubiquitousness of the word in our so-called Information Age left me as shaken as the first time I ever heard the word “software” as a kid; it made me think of meat, somehow made utilitarian. In Pushwagner’s book, everything is “soft”—the city, the television, and yes, even the meat. I find it disquieting that he, William Blake–style, somehow divined all of this, circa 1970. (In another scene, shifting the point of view from the workers to the “boss,” said CEO utters the words “Oracle Filter” through a giant television screen at his hundreds of workers.) Strangely, some of the more effective and affecting aspects of this book are the obvious anachronisms that leak through its surface, revealing the epoch in which it was drawn: the company men in hats, the 1960s cars, the reel-to-reel tape of the CEO’s computer.

Advertisement

In the art world of the 1960s comics were almost uniformly perceived as trash, nothing more than a stand-in for the vacuity of American consumer culture (see: Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol). Pushwagner’s underground cartoonist contemporaries Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman embraced that trashiness, rubbing the establishment’s nose in a refreshing mélange of satire and sexual self-revelation, keeping the medium’s artistic potential alive and lively, but also without pointing to any ambitious long-form experimental fiction (Kim Deitch’s fine work being the standout, pioneering exception). Most curiously, Soft City falls into neither of these camps, either fine art- or underground comics-wise; ultimately, its tone feels dire and experimental; it wows visually but gets under one’s skin in an unfamiliar, uncompanionable manner, introducing the awkward revelations of 1960s experimental film, writing, and poetry to a medium at that point more popularly associated with superheroes. (Though to be fair, once Pushwagner finished it in 1975, it was only four years until the first RAW magazine—in which his pages, I think, it would have found a welcome aesthetic sympathy.)

In some ways, the book’s power seems all the greater now for its mid-twentieth-century origins; in the 1960s, the looming threat of an oppressive urban architecture seemed more dire to the West than it does today, but in the wake of the recent forced relocation of agrarian families to high-rise apartments in China, Pushwagner’s book seems undeniably oracular. In 1970, 36 percent of the world’s population was living in urban areas, and the United Nations estimates that number will mushroom to 66 percent by 2050. Are we also headed for such a horizonless, walled existence? The workers in China who manufacture the bottomless chasms we carry in our pockets, and into which we stare for hours, every day, may have some idea.

Adapted from Chris Ware’s introduction to Soft City by Hariton Pushwagner, published by NYR Comics October 4.