The Swedish Academy’s mid-October announcement regarding literature seldom fails to occasion second-guessing, if not outrage. Whenever a foreign writer mostly unknown to English speakers is awarded the Nobel, a certain constituency will suggest that the Swedes are trolling us. Whenever someone who is already a household name across the world gets it, a different faction is crestfallen, because he or she did not need the publicity. This has presumably been going on since Sully Prudhomme took it away in 1901, his honeyed verses to dance forevermore on every child’s lips.

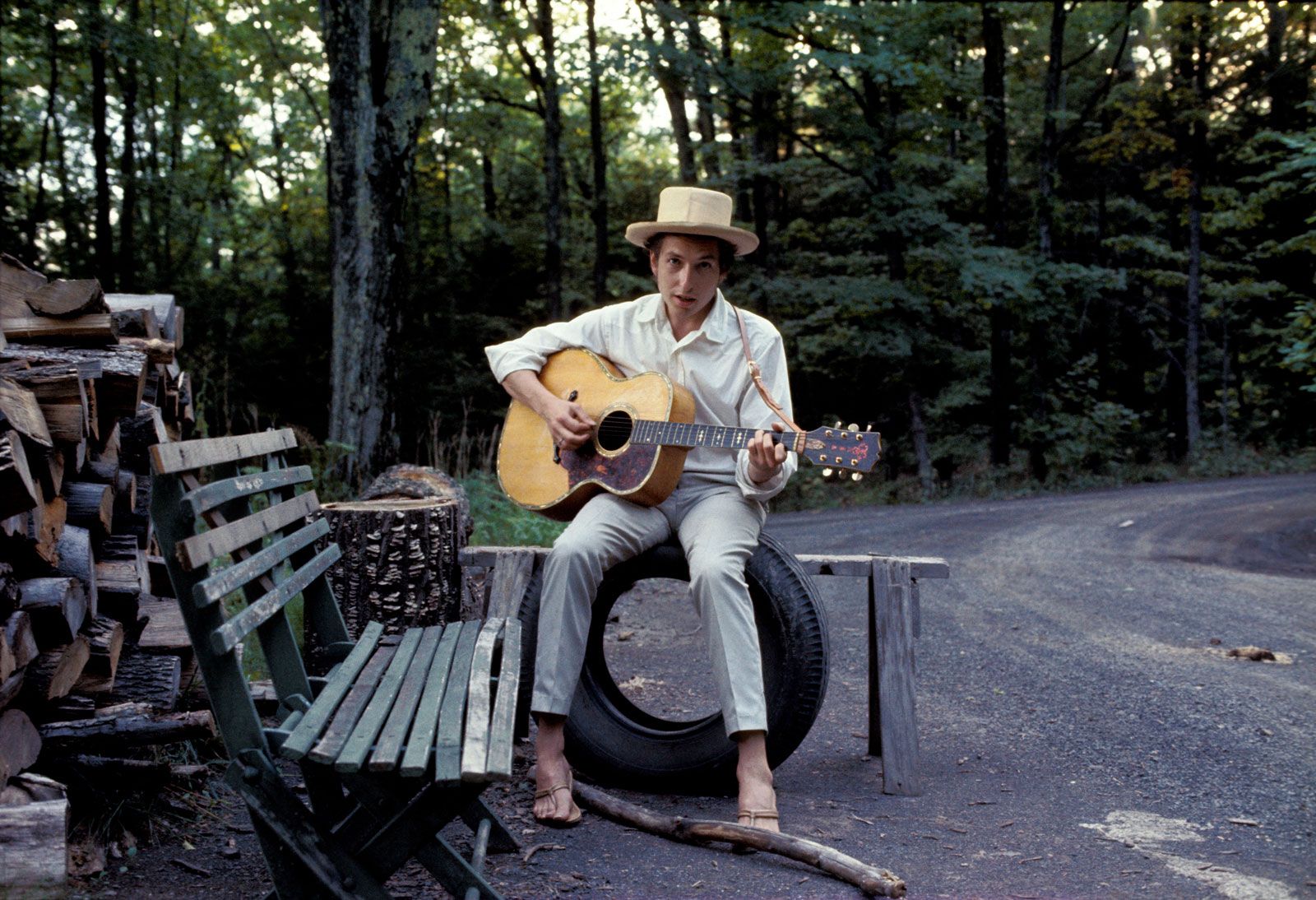

Bob Dylan was awarded the big prize this morning, and my social-media timeline has been alive with indignation ever since. The Nobel did not go to Ngugi wa Thiong’o, did not go to Ursula K. LeGuin, did not go to an overlooked novelist in a small country working in a seldom-translated language. But even more people are upset that the prize went to a “songwriter.” Some of those same people are still grousing that last year it was awarded to Svetlana Alexievich, a “journalist.” They have decided, for whatever reasons, that song lyrics and non-fictional prose do not qualify as literature. Which would come as a surprise to most writers before the mid-eighteenth century or so, although they have the disadvantage of being dead.

And people are upset because Bob Dylan is the voice of some generation other than theirs, because he works in a popular idiom, because he does not work in this minute’s popular idiom, because he appeared on a car commercial that aired during the Super Bowl, because his songwriting skills dropped off after this record or that one (the candidate albums are broadly varied)—because he was famous long ago. But note that phrase: “famous long ago.” Although undoubtedly people used it in speech and writing before Dylan was even born, it is nonetheless now tied to him: “…for playing the electric violin on Desolation Row.”

You may not think of Dylan as a poet, because his lyrics don’t always scan well on the page, but consider how many lines of poetry he has embedded in common discourse: “But to live outside the law you must be honest”; “She knows there’s no success like failure/And that failure’s no success at all”; “Ah but I was so much older then/I’m younger than that now”—those are just off the top of my head, and we could go on like this all night.

Somebody will argue that “You’re the top, you’re the Colosseum” rolls off the tongue just as trippingly, and nobody gave the big Swedish prize to Cole Porter. And somebody else will point out that “My smile is my makeup I wear since my break-up with you” does likewise, and that Dylan himself allegedly once named Smokey Robinson the greatest living poet in the nation, and where’s Smokey’s Nobel?

Song lyrics and poetry might have been interchangeable concepts for the Elizabethans, but two streams divided later on. As great as Porter and Robinson were as songwriters, they were working in—and profiting from—the air of frivolity that attended lyric-writing by the mid-twentieth century, an era that prized verbal dexterity and rapid evaporation. Dylan, through his ambiguity, his ability to throw down puzzles that continue to echo and to generate interpretations, almost singlehandedly created a climate in which lyrics were taken seriously. And Dylan accomplished something that few novelists or poets or for that matter songwriters (pace Joni Mitchell) have managed to do in our era: he changed the time he inhabited. Through words, with music as the fluid of their transmission, he affected the perception, outlook, opinions, ambitions, and assumptions of hundreds of millions of people all over the world.

The Nobel Prize in Literature cannot ever be all things to all people, and while this year’s award failed to accomplish various possible objectives, it was not in any way misapplied. Me, I just wish I’d had the foresight to plunk down a fifty on Dylan at Ladbroke’s. “The highway is for gamblers, better use your sense/Take what you have gathered from coincidence.”