Many of William Eggleston’s great photographs make a point of seeming to show nothing at all. Consider The Democratic Forest, a new book published in conjunction with an exhibition at the David Zwirner Gallery, including selections from 1983 to 1988 that convey quiet and sparse scenes of America (and not to be confused with his 1989 album of the same title). In his remarkable picture of a laundry room, for example, the white appliances sit squarely at angles to themselves, defining the neat and inglorious space in a harmony of edges. A vacuum cleaner and chair pose side by side, and a yellow laundry basket sits atop one of the machines, just to one side of a water heater in the corner, all of them like the attributes of a saint who forgot to appear in her own altarpiece.

And in this space where nothing is happening, where the photographer’s charge to himself seems to be, “Make a picture of nothing at all,” the emptiness takes on a special character. Note for example how different the laundry room is from Edward Hopper’s Rooms by the Sea, of 1951, the midcentury benchmark for the portentous depiction of empty rooms. In that picture, no matter how else we may gloss it, the existential grandeur of an elemental fate is impossible to miss.

Eggleston’s laundry room, by contrast, avoids the feeling of existential crisis. Instead the beauty of the scene derives from the simple geometries of a feminine space, a domestic one, not unlike some of the other subjects in this book (Eudora Welty’s simple curtained kitchen window, for example). And those beauties, allowed to remain unsung, begin to echo with their own emptiness.

That emptiness is not a woman’s forlornness, and not Eggleston’s own, but rather that of the scene itself. For once the humble things of the world are spared the weight and freight of having to portray our tortured and disappointed states of being. The art of picturing, to put it another way, is to recognize how resistant the world is to picturing. And that is funny, the way the photographer calls attention to our wish to aggrandize and personalize the humble things that, left to their own devices, will sooner or later start to hum with their own gentle stupidity, to tell the joke of themselves; and, in so doing, of us.

But Eggleston’s emptiness has other forms. Take his great photograph of the vacant concession stand. Painted pink with a yellow interior, the stand is flanked by matching plastic garbage cans and set back on cement painted in a four-square pattern of pale blue and yellow. The solemnity of this frivolous structure! It reminds me strangely of the villa of Pontius Pilate at background left in Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation of Christ, painted in the 1450s. The architecture of Pilate’s home, with its mathematical recession of floor and ceiling, is no more stately than Eggleston’s vacant refreshment booth. The dignity of Eggleston’s scene is enough to make one think of Piero having been commissioned to paint an altarpiece for an amusement park, only to have abandoned his would-be Madonna of the Sno-Cone Stand because of lack of payment, or a sudden war or plague, the painting remaining forever after with only the architecture and not the figures finished.

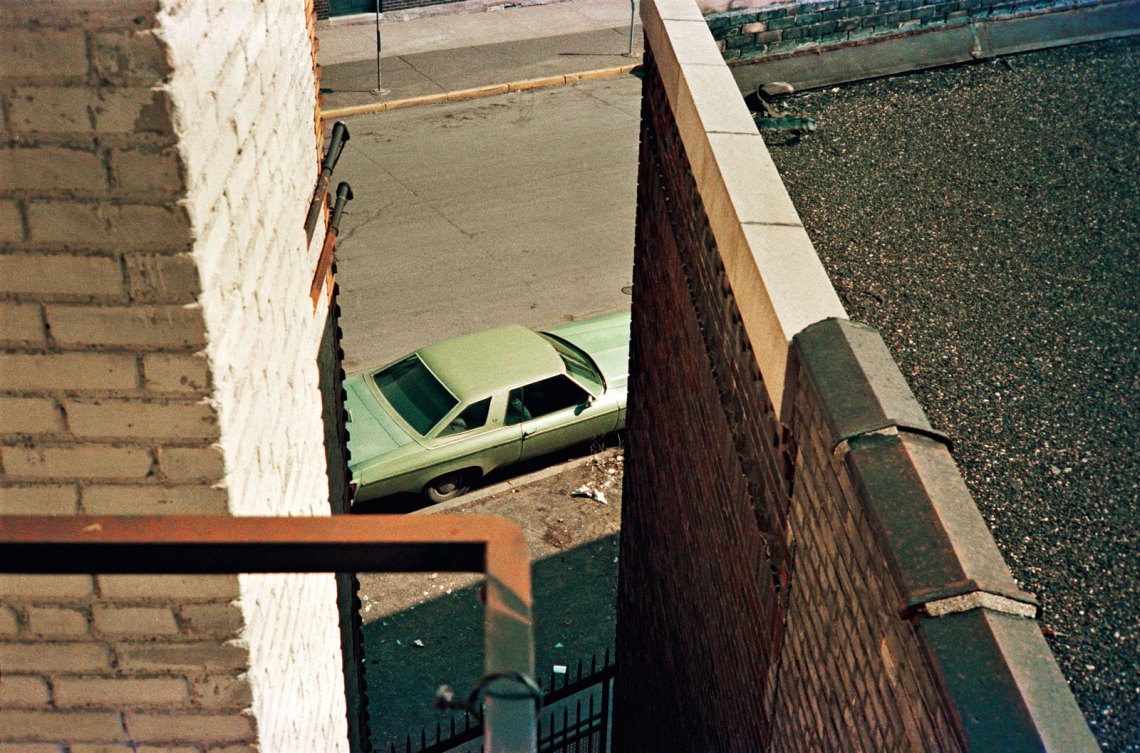

The same might be said of Eggleston’s beautiful photograph of the two telephone booths on a Pittsburgh street. Here is an even more Piero-like setting of nearly miraculous geometry—the anonymous booths and iron railing, not to mention the illuminated windows and streaked walls, all of them beyond exegesis. Or his remarkable tripartite picture of the auto garage, with the street view to the left, the white wall and closed door at center, and the brooding darkened interior to the right, revealed by a raised garage door. Do such places look resigned because they resemble crime scenes? Or is it in fact that nothing special happens there that makes them so patiently forlorn? Either martyrdom is an American matter of fact, or the matter of fact is a kind of American martyrdom.

Advertisement

Eggleston’s vacancy in these pictures is religious, or sadly religious. Seizing on the blankness as the very thing to see, he joins the poet Wallace Stevens in voyaging through the God-less realms where it is left to the hapless twentieth-century self, embarked on its own idiotic quest, to discern the difference between the “Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.” A notoriously tricky line, yes, but one I take to mean—thinking of Eggleston—that you must look carefully to see the difference between ordinary garden-variety blankness and a kind of blankness that resonates with some old supernatural mystery. The blades of Eggleston’s ceiling fan are angel’s wings.

Adapted from Alexander Nemerov’s introduction to William Eggleston: The Democratic Forest, Selected Works, published by David Zwirner Books. William Eggleston: The Democratic Forest is at David Zwirner Gallery through December 17.