Like other Japanese exports—sushi or judo, haiku or Zen—the art form known as manga has evolved amid its long history of Pacific crossings. Today, we think of manga as graphic stories, the Japanese equivalent of comic books. But during the nineteenth century, manga referred to informal drawings, sequential or not, seemingly dashed off by their inspired creator. No artist was more closely associated with manga than the amazing painter and printmaker who called himself, among some thirty other fanciful names, Hokusai (“Northern Studio”) Katsushika (1760-1849), best known, outside of Japan, for his mesmerizing series of landscape prints Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (c. 1830-31), published when he was already in his seventies.

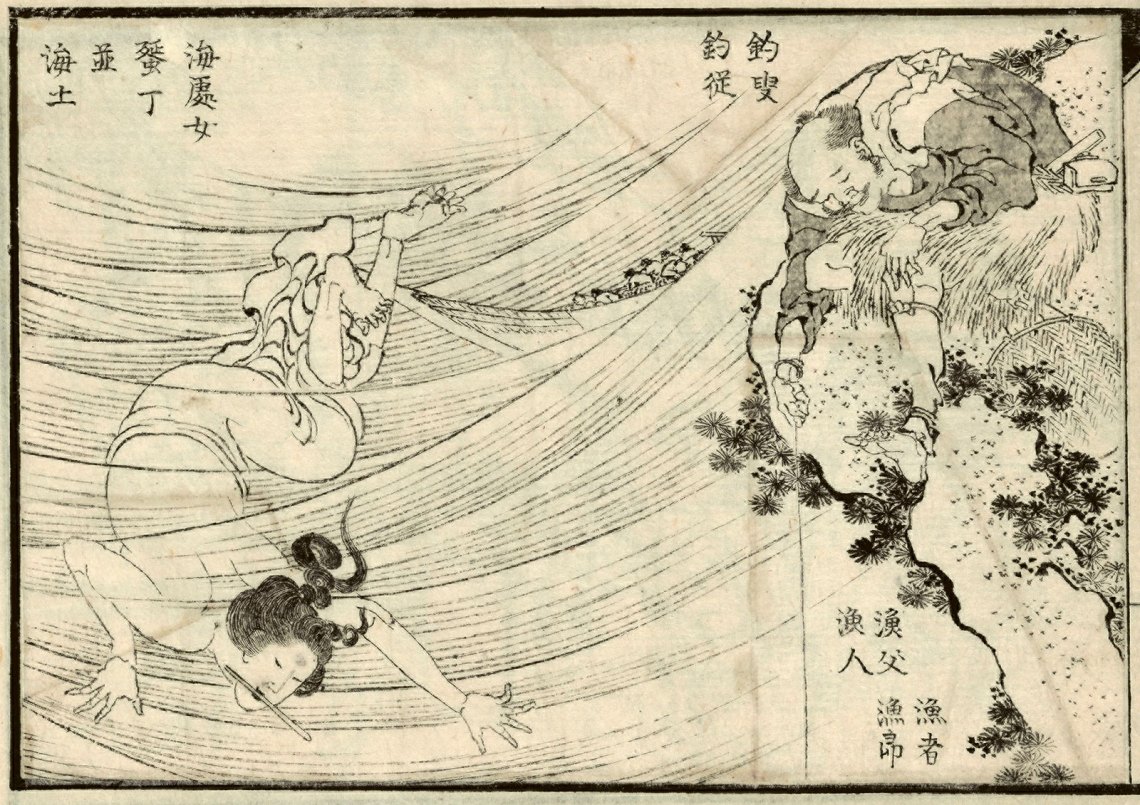

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, had long possessed—in its fabulous collection of Japanese art unparalleled anywhere outside Japan—an anonymous album of drawings long assumed to be by Hokusai. That album has now been persuasively linked to the artist, through art-historical detective work, via a hitherto mysterious publisher’s advertisement, from 1823, for Master Iitsu’s Chicken-Rib Picture Book. (Iitsu was one of Hokusai’s many disguises; the title might thus be translated, as MFA curator Sarah E. Thompson notes, “Hokusai’s Tasty Morsels.”) The volume of tasty morsels remained unpublished—until now. The cover displays a partially clothed abalone-diver swooping down on her prey with a knife between her teeth. She seems just the right official greeter for Hokusai’s incisive art.

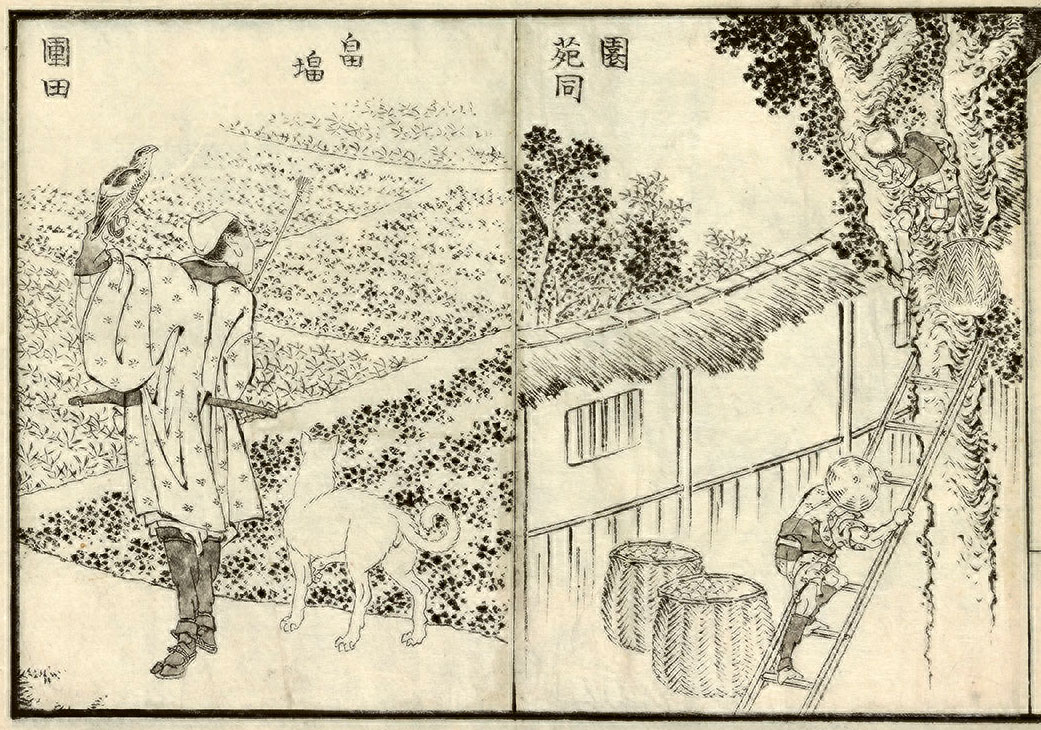

When French artists like Manet and Degas first encountered Hokusai’s manga, in fifteen volumes numbering some 4,000 plates, it was the disjunctive, off-the-cuff quality of the images that proved most exciting. Hokusai seemed to be a Japanese flâneur, sketchbook in hand, who quickly took down whatever he saw on his travels or in his teeming imagination. Again and again in Hokusai’s Lost Manga, travelers take a break from their journeys—up craggy mountains, down dangerous rivers—to scrutinize the countryside. A dapper falconer, a hawk perched on his shoulder, looks out over carefully tended fields. A dog beside him reinforces the intent gaze of hawker and hawk. This is how to view this variegated world, Hokusai seems to say, in plate after plate in this visually arresting album.

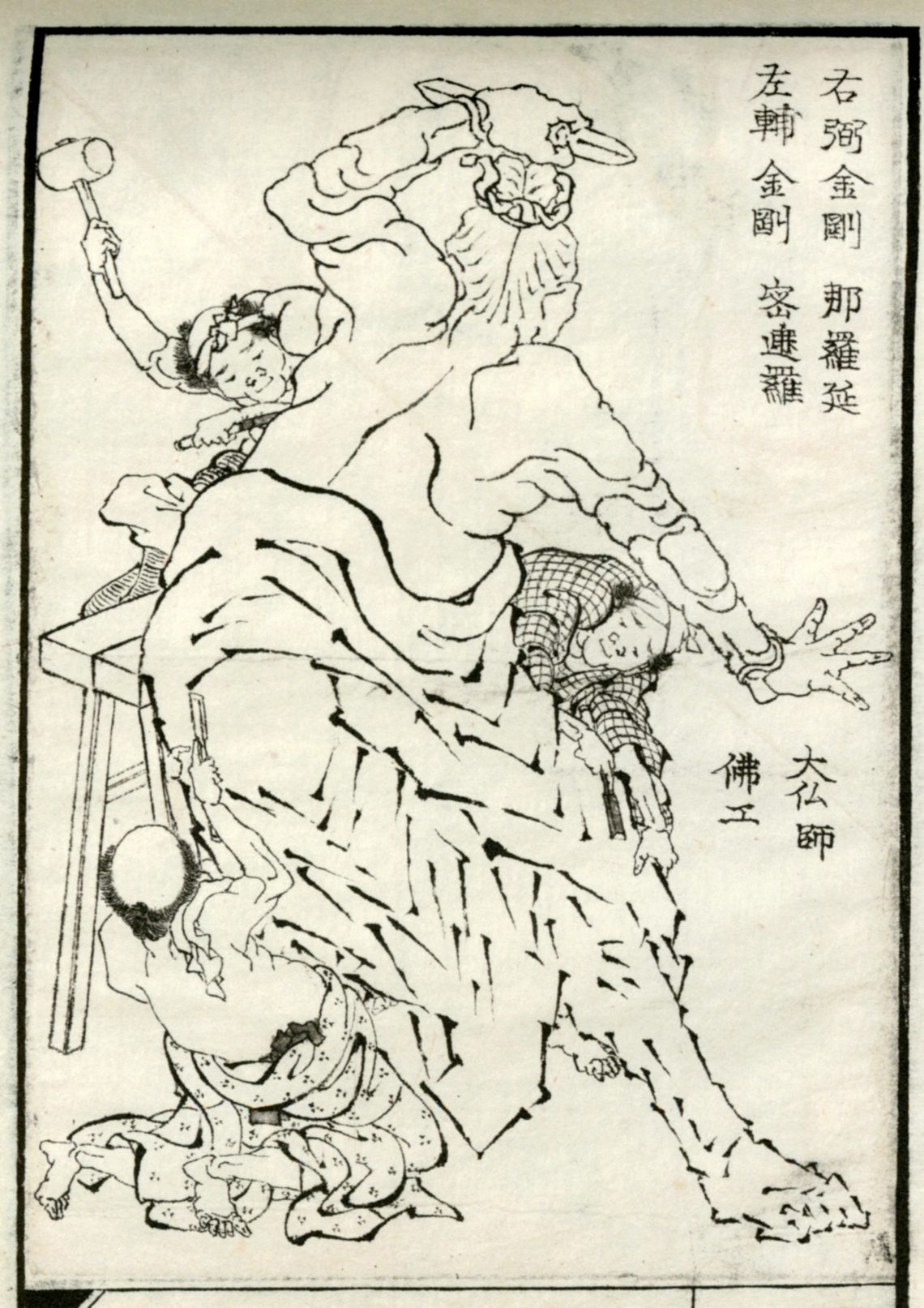

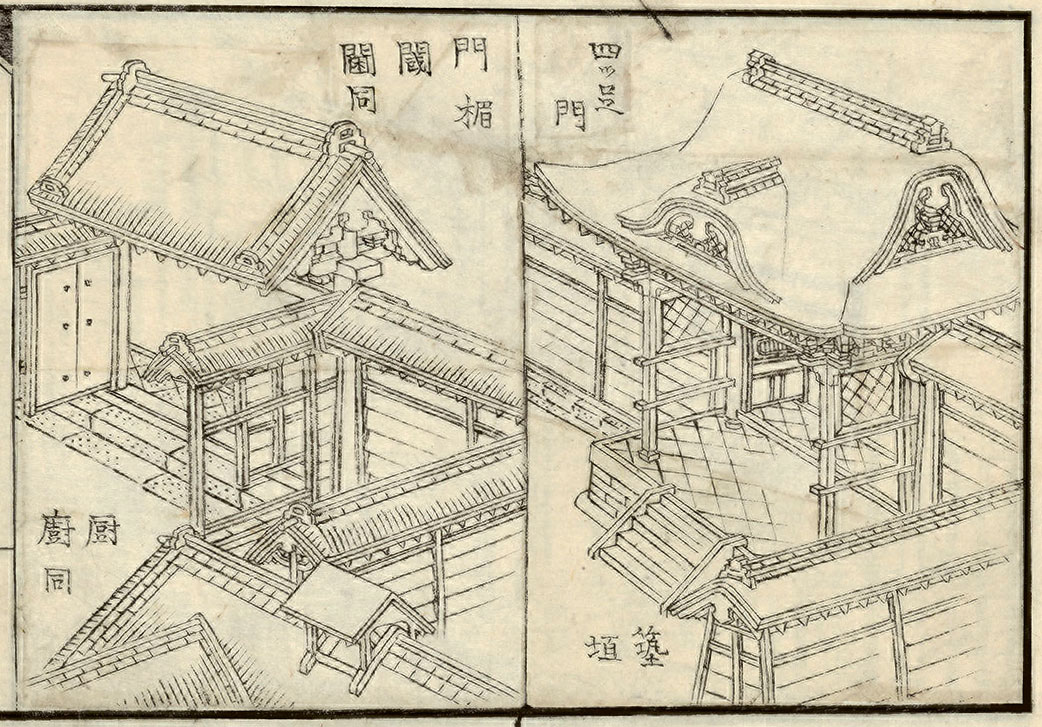

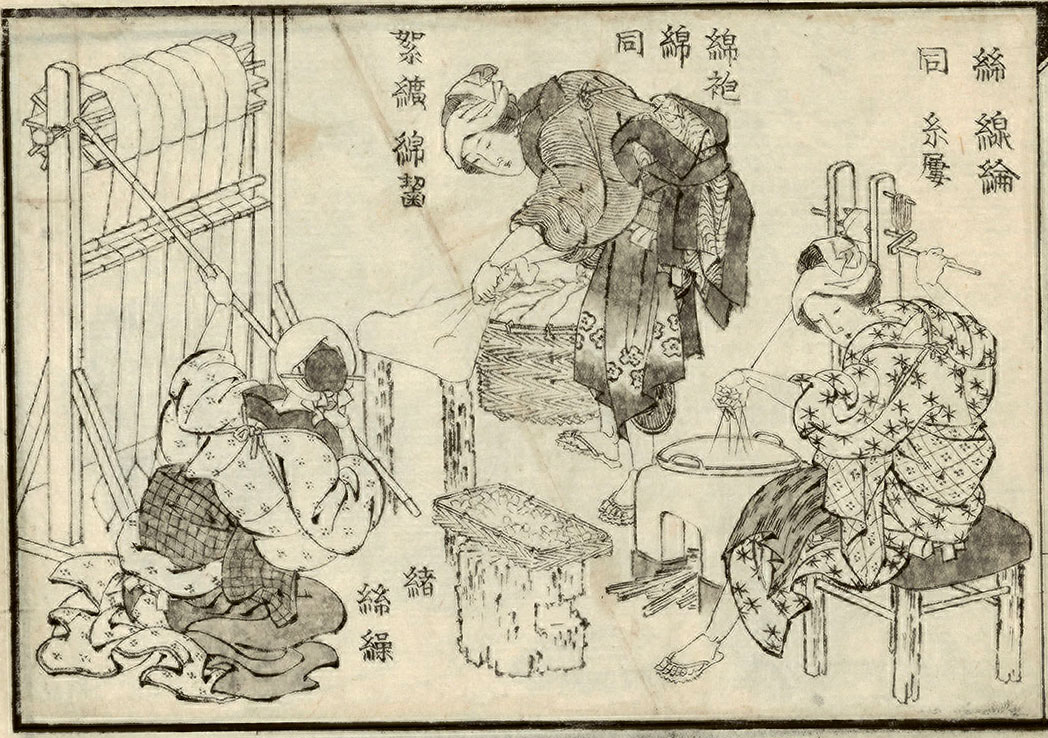

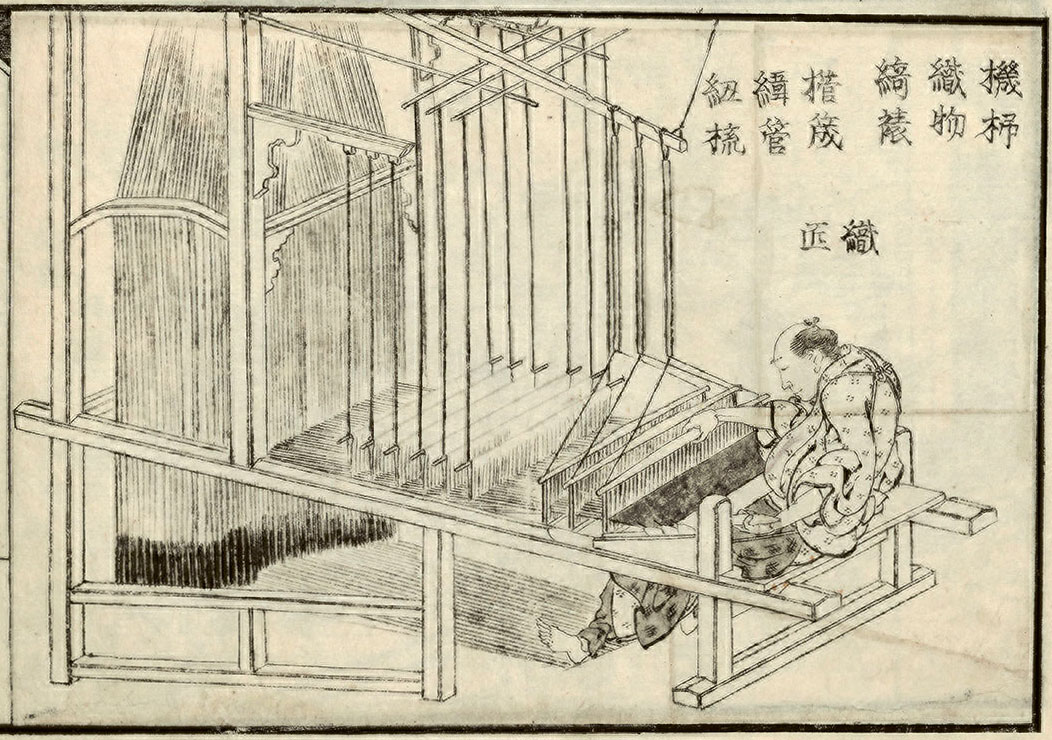

But Hokusai wasn’t just a sharp-eyed observer; he was also an exquisite and extremely well-informed craftsman, eager to pilfer whatever he could use from Western artists or the latest developments in chemical dyes. Some of the most absorbing plates in the Boston album are closely observed depictions of master craftsmen at work. In one picture, a weaver sits at a loom so enormous that it takes up almost the whole frame. We can see all the elaborate machinery of warp and weft, like a great organ at which he has just sat down to play. The pattern he is weaving is unspooling, like music, from his alert hands. In another energetic image, drawn from a No play, a pair of swordsmiths wearing ceremonial fox-hats take turns hammering a peerless blade while a mysterious deity lends a hand to the task. So vigorous are the hammer blows that one hammer leaps beyond the border of the page. In yet another image, two sculptors, dwarfed by their task, carve a huge statue to guard a temple. This image seems the most self-reflexive for Hokusai, with the roughed out form of the statue resembling an unfinished woodblock print.

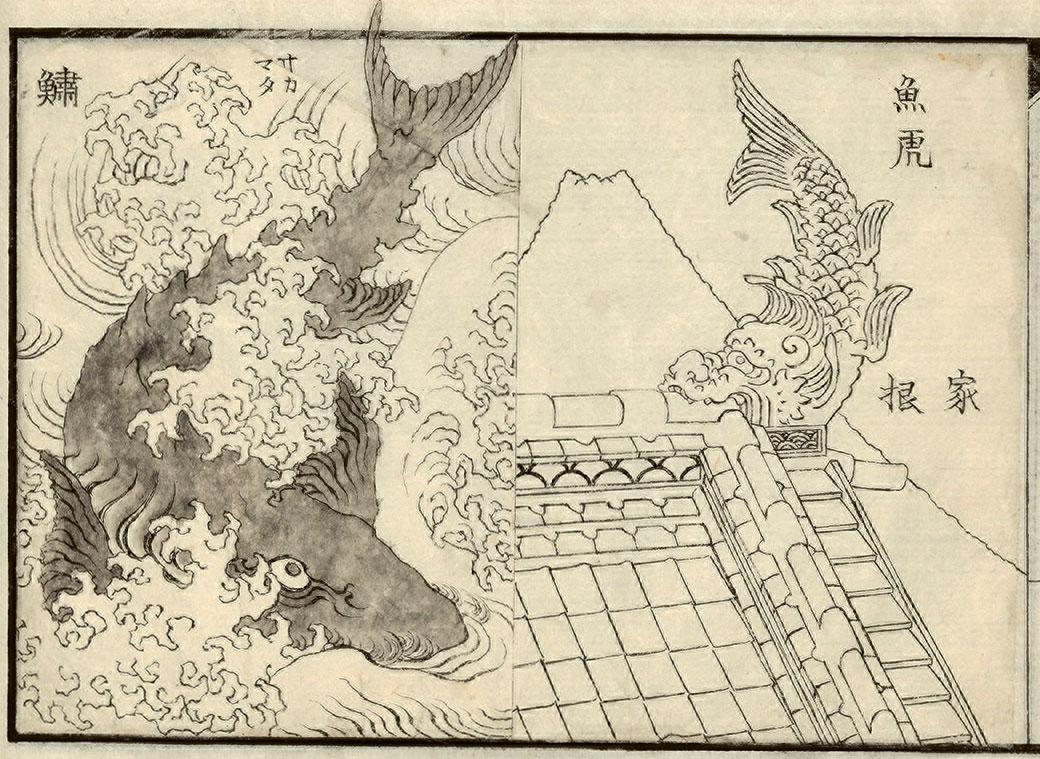

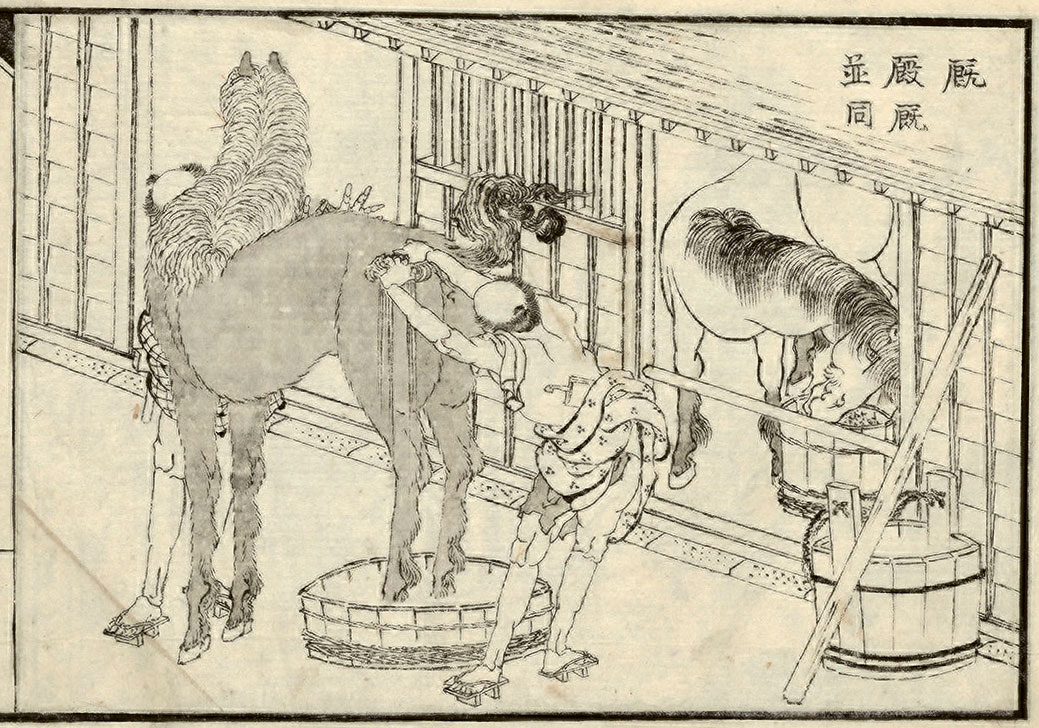

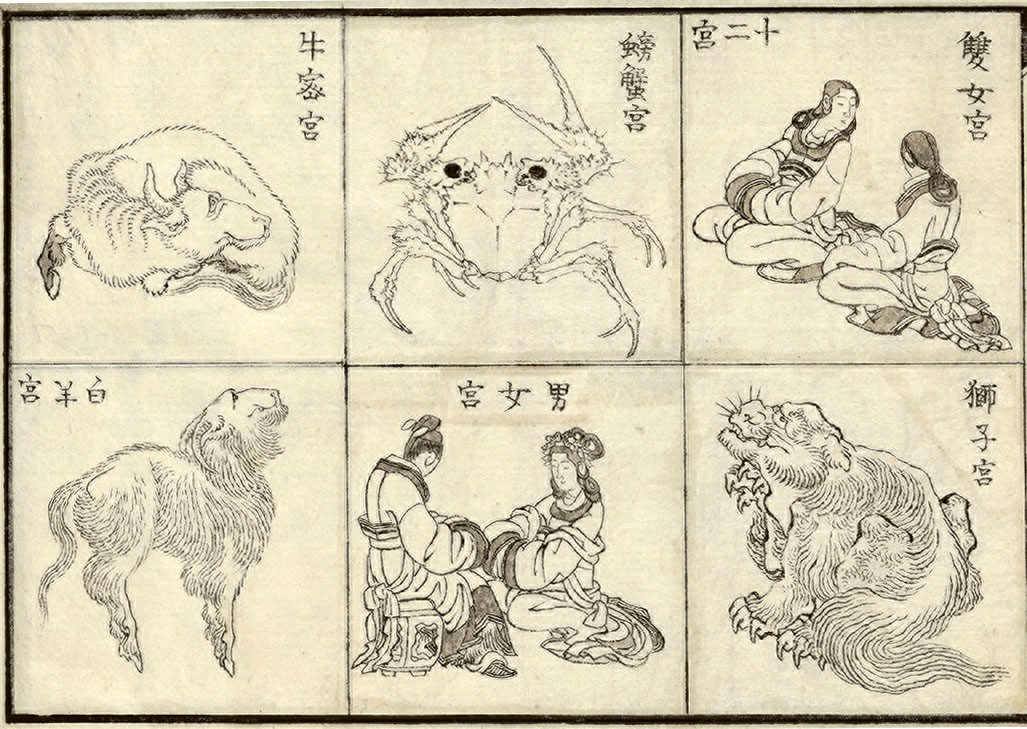

Elsewhere in the book, readers familiar with Hokusai’s work will recognize the master experimenting with images that later made him world-famous: the dramatic portrait of a great wave cresting threateningly, which would become the single most familiar image in all of Japanese art; a charming picture of grooms stretching their arms to wash a horse, which Hokusai would later place in front of a waterfall, as though a great deal of water was needed for the job. Another print pairs a sea monster, slicing menacingly among Hokusai’s trademark claw-like waves, with a roof-ornament of the same monster—like a gargoyle chomping on a ridgepole—while Mount Fuji looms in the background. “Real or imagined, it’s all the same to me,” Hokusai seems to say.

Advertisement

Hokusai’s Lost Manga is published by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.