When Carmen Herrera is asked to explain her paintings in Alison Klayman’s film about her life and work, The 100 Years Show (2015), she says, “If I could put those things in words, I wouldn’t do the painting. I would tell you…Usually artists are not the best people to talk about art. I think it’s a great mistake. You cannot talk about art—you have to art about art.”

Herrera, now 101 years old, has spent the better part of a century doing just that. For most of that time, the world paid scant attention to her “arting”: only in the last decade has she been granted the attention she should by rights have received half a century ago. As a Cuban, as a woman, she found little public support in the New York art world. Reluctant to be classified by national origin or gender, she struggled to find a place, but continued to produce work, prolifically, for decades: “I kept going,” she says in Klayman’s film. “I couldn’t stop.”

Herrera paints or draws daily even now, and her work has remained an exhilarating example of hard-edged abstraction. Inspired by Miró and Mondrian, a friend of Barnett Newman and of Leon Polk Smith, a young artist in post-war Paris at the same time as Ellsworth Kelly, she is an artist for whom the pure line remains the source of inspiration and joy (“I like straight lines…I like order. In this chaos that we live in, I like to put order,” she explained in a 1994 interview). A recent discovery for audiences, she may appear, like Athena, to have sprung fully formed into the world when she sold her first painting in 2004, at age 89. But it is simply that we have been painfully oblivious: Herrera’s work has been waiting for us all along.

The current exhibition of Herrera’s work at the Whitney Museum, entitled “Lines of Sight,” with a beautiful accompanying catalogue by Dana Miller, endeavors to rectify the art world’s long-term neglect: it focuses on Herrera’s work from 1948-1978, from her earliest abstracts through the various stages of her artistic evolution. Miller’s central catalogue essay is illuminating and rich, and the catalogue further offers valuable insight into Herrera’s place in Cuban art, her French experience, and what might be deemed the hemispheric setting of work, her connection to Latin artists in the Americas.

Born in Havana, Cuba in 1915, Carmen Herrera was the seventh and last child of well-to-do parents. Her father founded the newspaper El Mundo, and her formidable mother was an early feminist. In 1939, Herrera married an American, Jesse Loewenthal, and moved to New York, where—with the exception of five years in Paris from 1948-1953—she has lived since. (Her long marriage was happy, and her husband’s faith and support were crucial to her as an artist. “I wish my husband had seen it,” she says of her success. “He saw the artwork, but he didn’t know that I was going to be popular.”) Having initially studied architecture, she gravitated early to painting, studying on scholarship at New York’s Art Students’ League in the early 1940s. But it was in Paris that she found herself as an abstract artist, discovered the work of the Bauhaus, of Josef Albers, of the Russian Suprematists, and joined the coterie of artists known as the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, an association of abstract artists. It was there, too, that she painted the earliest of the works on view at the Whitney.

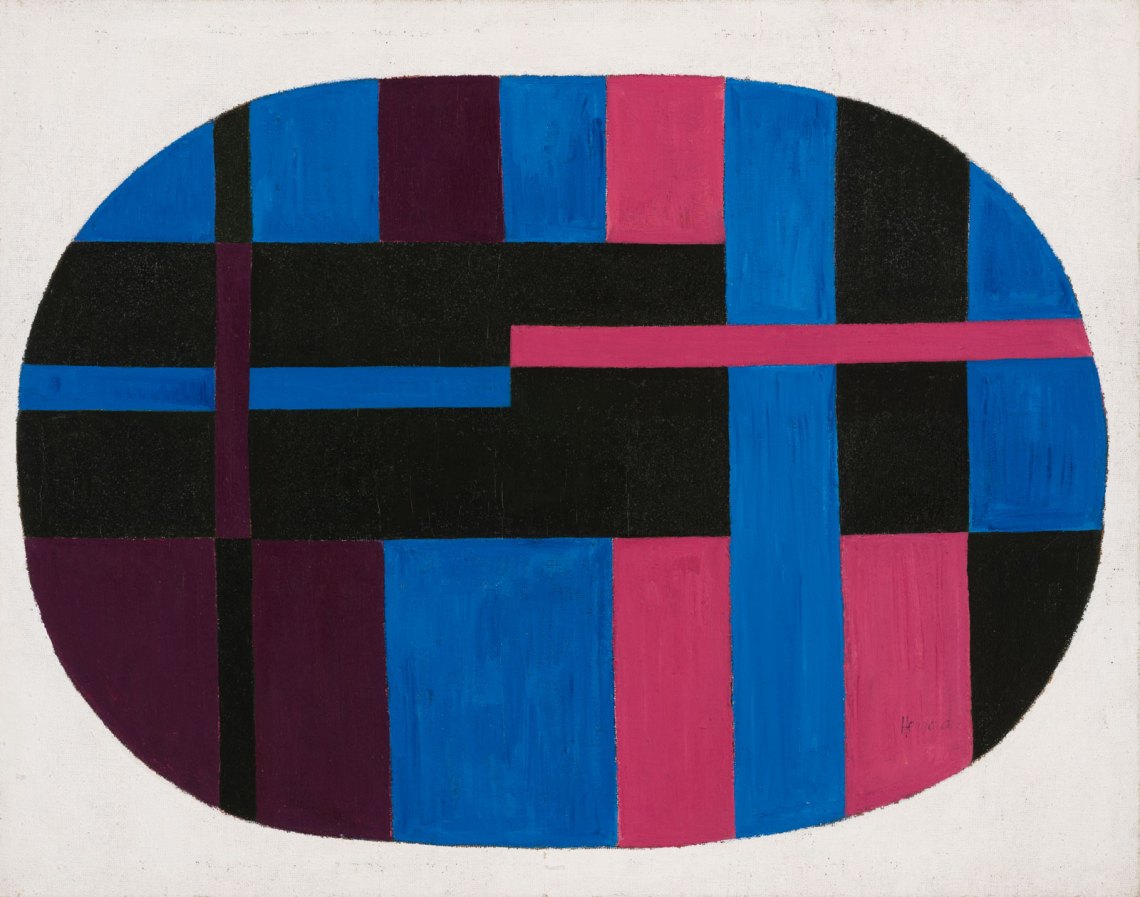

From the first, Herrera deployed line and color with an energy intensified by her rigor. A City (1948), with its blocks of lemon yellow, black, and cobalt blue, foreshadows a palate that recurred in later series. More visually complicated than her later paintings, it evokes, with its sharp juxtaposed turrets of light and dark overlaying broken oblongs of opposing color, the architecture and bustle of urban life. It is hard not to smile at Herrera’s witty use of the rectangular burlap frame and within it, the squared oval of tri-colored paint, which in turn contains the measured interplay of various geometrical forms. A City affords us both formal satisfaction and its sly frustration; it points to things, and elicits emotion, but insists, still, on its openness, its detachment.

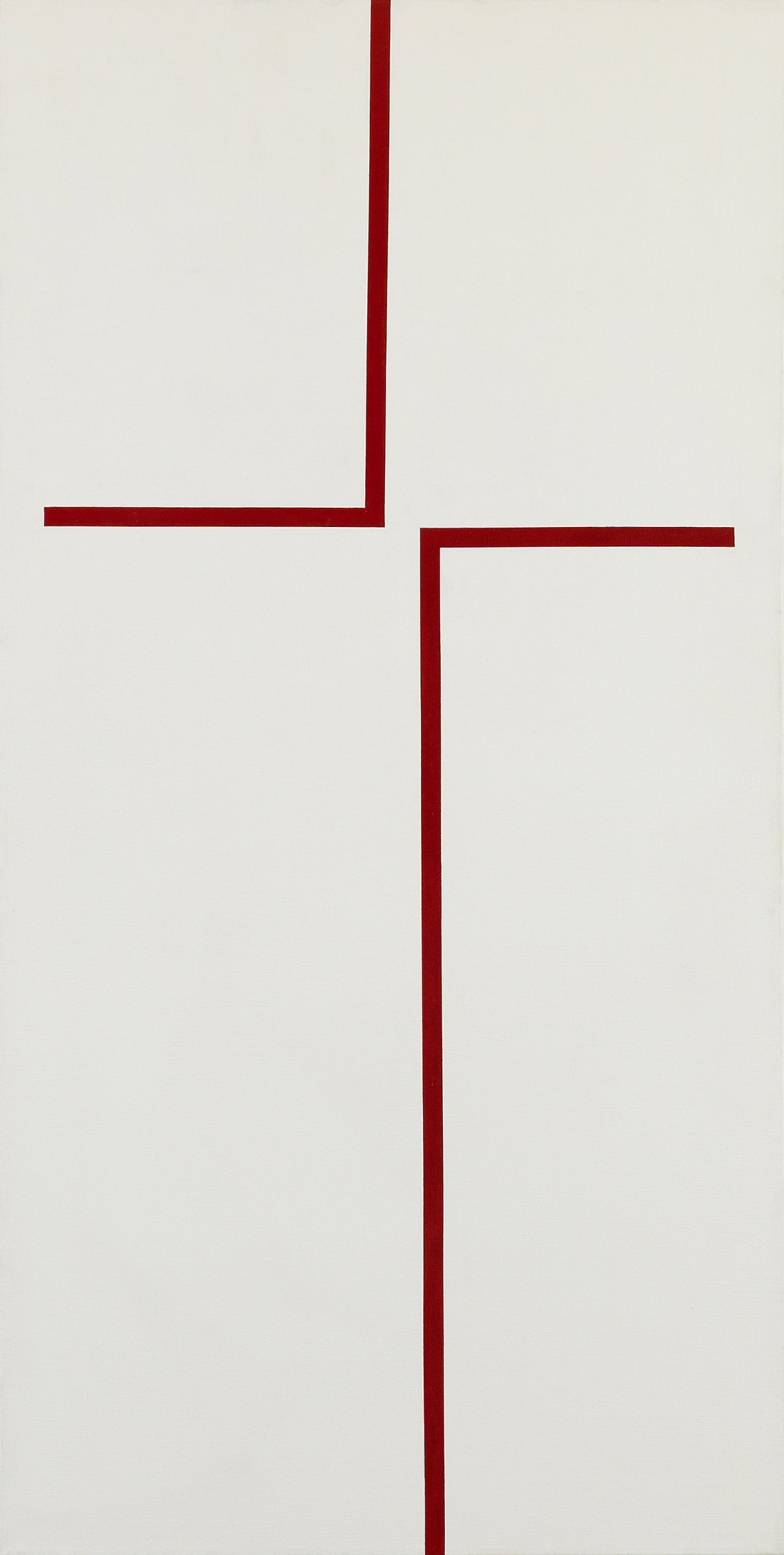

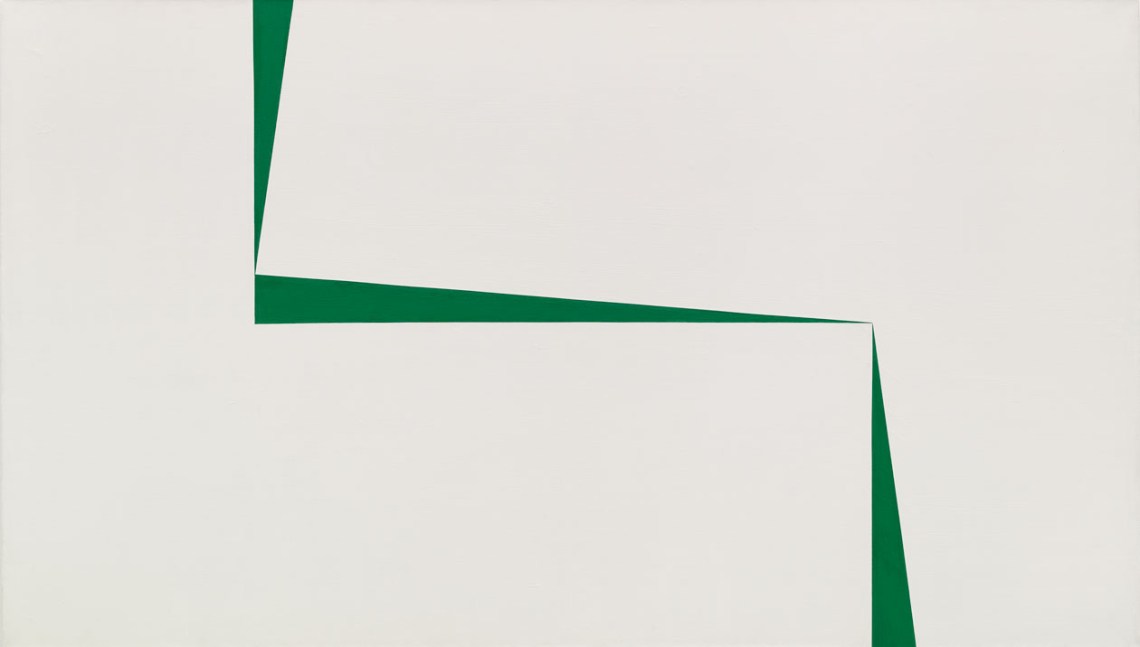

This tension between form and freedom—the paradox that fierce constraint, or restraint, can allow for the greatest liberty—becomes only ever more apparent in Herrera’s oeuvre. In her Blanco y Verde series (one of which has been acquired by the Whitney) she explores that balance with a radical purity, her nearly all-white canvases ruptured by jagged elongated emerald triangles that sing to, or spar with, one another: all but touching like the fingertips of Adam and God in Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam; or piercing the canvas like an intense shaft of green light; or pointing thinly westwards, like the needle on a dial. There aren’t words, of course, or similes, for what these paintings are or what they do: as Herrera says, they stand for themselves, and each is only the expression of its intention.

Advertisement

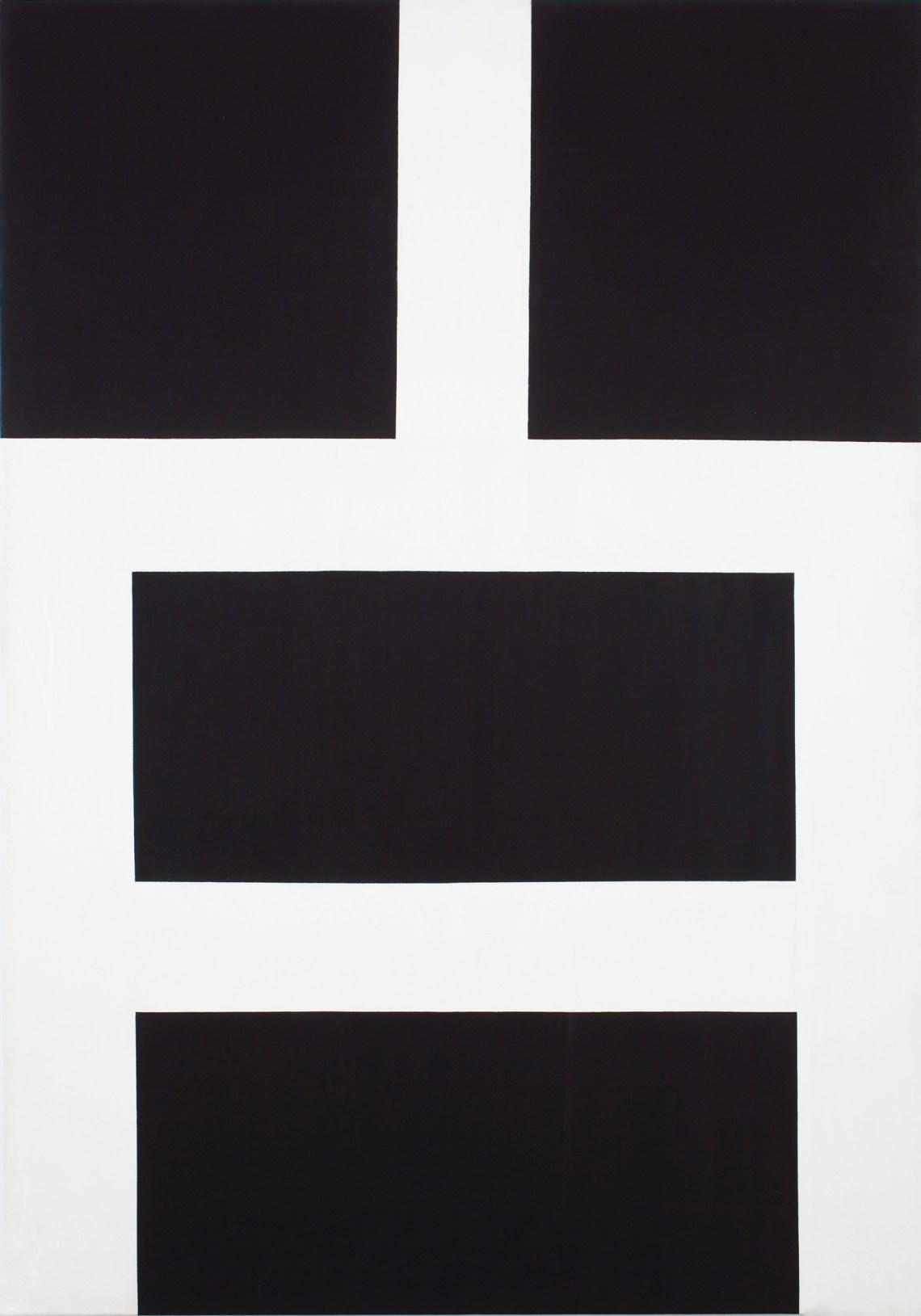

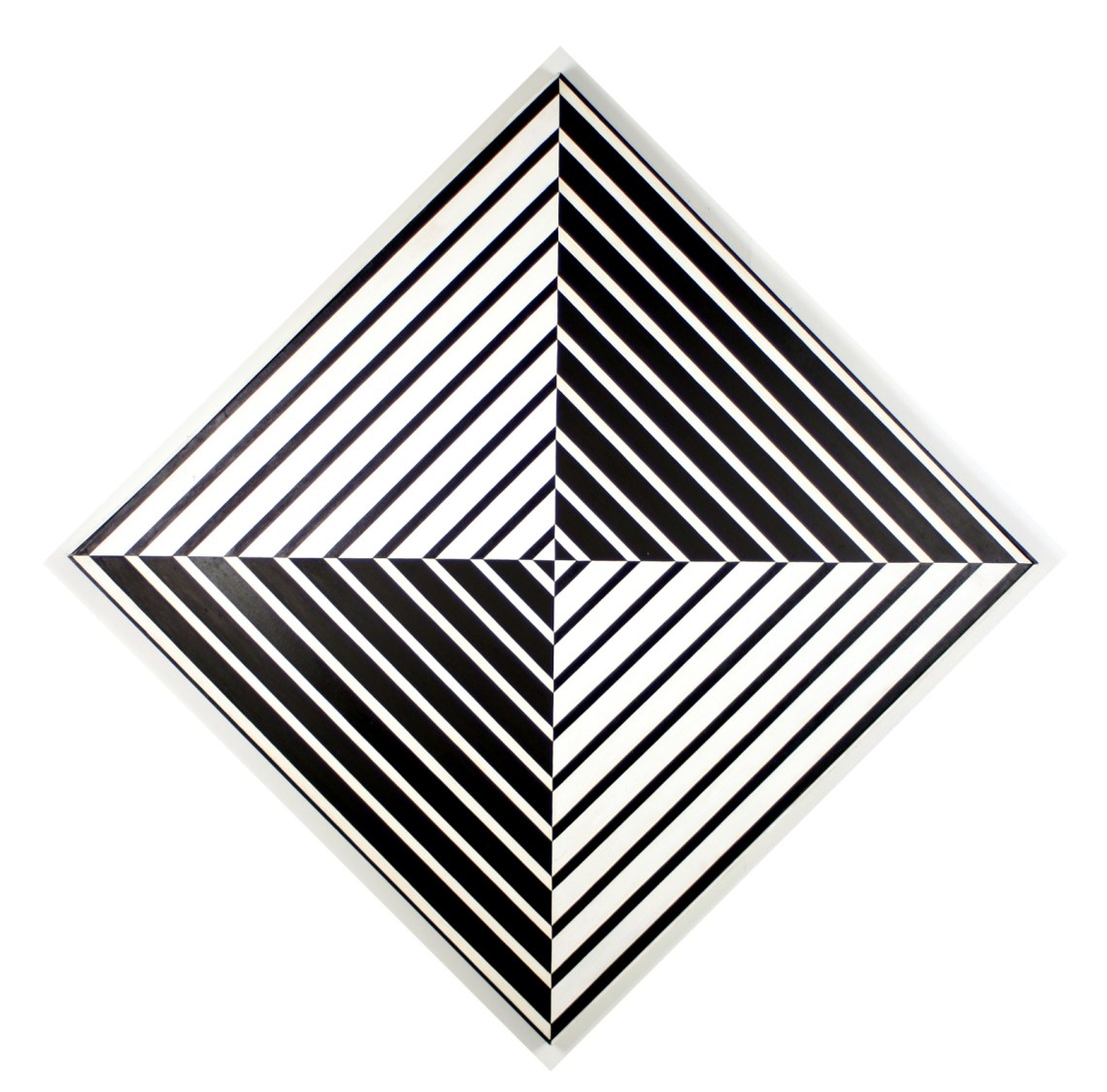

That this intention has a spiritual component can sometimes be powerfully felt. The purity of Herrera’s lines is nowhere more evident than in her many black-and-white paintings: as she has said, “You cannot lie when you have a black-and-white painting.” Some of these from the 1950s —such as Black and White (1952)—prefigure the Op Art movement by a decade; others, much later, are meticulously architectural. All are animated by Herrera’s brisk humor. Escorial (1974) is Herrera’s response to San Lorenzo del Escorial, the sixteenth-century Spanish royal monastery and palace, of which she explains: “It was a garbage dump and now it’s a royal palace. And even more fun, El Escorial was designed as a symbol of Saint Lawrence, who was barbecued…and this is a grill.”

Surely few art critics would have the audacity to liken Herrera’s painting to a barbecue, but the analogy works: it does look like a grill. And like an architect’s drawing of a monastery. And like a form of prayer. And because Herrera, slyly, is in the business of “arting” rather than explaining, it can be all of these things at once. She is a firm believer that less is more: “I have something that I think is finished,” she explains, “and I take something out, and it’s better.” The resulting paintings are, quite literally, essential.

For audiences, the revelation over the past decade of Herrera’s bold and vital work is a glorious gift. The paintings and sculptures are exciting precisely because they allow for so much, while insisting, firmly and with order, upon very little. It is not too much to say this is art as a form of politics: the opposite of tyranny, and hence all the more important today. For Herrera, with the wisdom of a century, the pleasures of exhibition are genuine, but tempered. “It’s about time,” she has said, about being shown at the Whitney. “Better late than never… A little earlier would have been nice.”

“Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight” is at the Whitney Museum of American Art through January 9.