The annual awards for best science fiction are called “Hugos.” A futuristic story by William Gibson in 1981 was called “The Gernsback Continuum.” But except for a few markers like these, Hugo Gernsback (1884-1967) has mostly vanished from our cultural memory, which is a pity, because he was an extraordinary man, and his influence on our modern age—electrical, science-permeated, and full of wonders—was outsized.

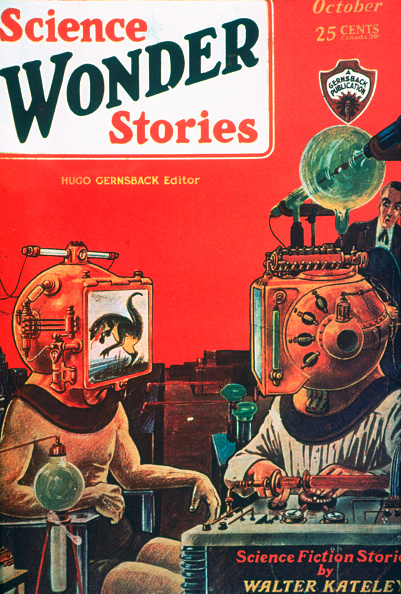

Gernsback is sometimes called the father of science fiction, though not because of any he wrote himself. (He did self-publish one novel, Ralph 124C 41+: A Romance of the Year 2660, which Martin Gardner called “surely the worst SF novel ever written.”) He gave the new genre its name in the 1920s, when he published “pulp” magazines like Amazing Stories and Science Wonder Stories in which eager writers could ply their trade for pennies a word (when he paid them at all). “By ‘scientifiction,’” he declared, “I mean the Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, and Edgar Allan Poe type of story—a charming romance intermingled with scientific fact and prophetic vision.”

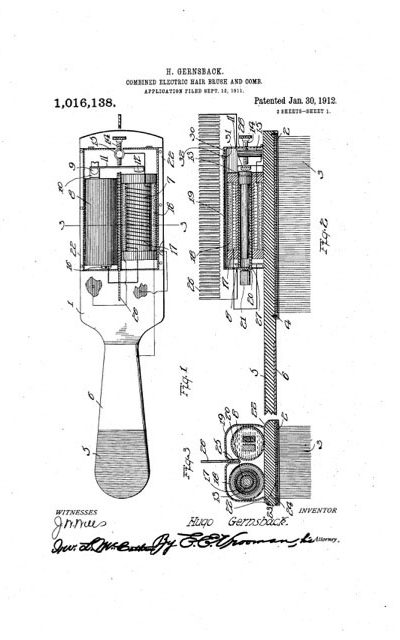

First, though, he was a radio man, immersed in and obsessed with the new technology of wireless communication. He was an inventor in the turn-of-the-century generation inspired by Thomas Edison; among his eighty patents are “Radio Horn”; “Detectorium”; “Luminous Electric Mirror”; “Ear Cushion” (for telephone receivers); “Combined Electric Hair Brush and Comb” (“may also be used as a massage instrument”). He formed the first radio hobbyist group, the Wireless Association of America, when he was twenty-five years old, and incorporated its successor, the Radio League of America, six years later; created Radio News magazine; and started one of New York’s first stations, WRNY, broadcasting from atop the Roosevelt Hotel on Madison Avenue. The station and the league promoted the magazine, and the magazine promoted the station and the league, and all promoted Gernsback. He was an evangelist for the church we might call electronic culture. Most of us are its parishioners nowadays, with our magic boxes.

Gernsback left a trail of technical writings, patents, interviews, newspaper clippings, and prophetic essays, and the best of these have now been gathered into a beautifully illustrated compendium and sourcebook titled The Perversity of Things: Hugo Gernsback on Media, Tinkering, and Scientifiction, by Grant Wythoff, a Columbia University historian of media studies. Wythoff sees his subject as, above all, a “tinkerer.” What is a tinkerer? Edison had used the word “mucker.” A tinkerer or mucker is a scientific experimenter without portfolio, trying not to put on airs.

“Today,” writes Wythoff, “we might refer to people who take pride in their ability to build seemingly complex technologies from scratch as makers. Not just a hobby, tinkering in the early twentieth century was a special form of intuition or creativity, a means of advancement for a self-educated working class.” The community organized around wireless grew to number hundreds of thousands of amateurs exchanging call signs and codes. Economically and politically, tinkering meant building technology from the bottom up rather than the top down. Amateurs rather than corporate research labs. Today’s hackers are the heirs of Wythoff’s tinkerers. “Gernsback’s handicraft futures seemed so seductive because they were futures that you, the reader, could build yourself,” Wythoff notes.

Until now, the record of Gernsback’s life has been scanty and quite unreliable. It’s not easy even to count his different magazines, so often did they subdivide, merge, and change names and ownership in hopes of evading creditors. (The many writers he stiffed may have included the darkly brilliant—and, as Wythoff notes, “spectacularly racist”—H. P. Lovecraft, who called him “Hugo the Rat.”) His public biography rests mainly on, as Wythoff says, “self-propagated stories that border on braggadocio.” (I wrote in my book Time Travel that Gernsback was “what people of a later time would term a bullshit artist,” a comment that doesn’t seem to require correction.) His writings veer freely between the scientific and the fantastic. “The reader will find technical precision and utopian speculation in varying proportions,” Wythoff says, and for Gernsback it’s all of a piece.

Born Hugo Gernsbacher, the son of a wine merchant in a Luxembourg suburb before electrification, he started tinkering as a child with electric bell-ringers. When he emigrated to New York City at the age of nineteen, in 1904, he carried in his baggage a design for a new kind of electrolytic battery. A year later, styling himself in Yankee fashion “Huck Gernsback,” he published his first article in Scientific American, a design for a new kind of electric interrupter. That same year he started his first business venture, the Electro Importing Company, selling parts and gadgets and a “Telimco” radio set by mail order to a nascent market of hobbyists and soon claiming to be “the largest makers of experimental Wireless material in the world.”

Advertisement

His mail-order catalogue of novelties and vacuum tubes soon morphed into a magazine, printed on the same cheap paper but now titled Modern Electrics. It included articles and editorials, like “The Wireless Joker” (it seems pranksters had fun with the new communications channel) and “Signaling to Mars.” It was hugely successful, and Gernsback was soon a man about town, wearing a silk hat, dining at Delmonico’s and perusing its wine list with a monocle.

Public awareness of science and technology was new and in flux. “Technology” was barely a word and still not far removed from magic. “But wireless was magical to Gernsback’s readers,” writes Wythoff, “not because they didn’t understand how the trick worked but because they did.” Gernsback asked his readers to cast their minds back “but 100 years” to the time of Napoleon and consider how far the world has “progressed” in that mere century. “Our entire mode of living has changed with the present progress,” he wrote in the first issue of Amazing Stories “and it is little wonder, therefore, that many fantastic situations—impossible 100 years ago—are brought about today.”

So for Gernsback it was completely natural to publish Science Wonder Stories alongside Electrical Experimenter. He returned again and again to the theme of fact versus fiction—a false dichotomy, as far as he was concerned. Leonardo da Vinci, Jules Verne, and H. G. Wells were inventors and prophets, their fantastic visions giving us our parachutes and submarines and spaceships. “In time to come,” he wrote in one editorial, “there is no question that science fiction will be looked upon with considerable respect by every thinking person.” He declared, and believed, that science fiction would be the true literature of the future.

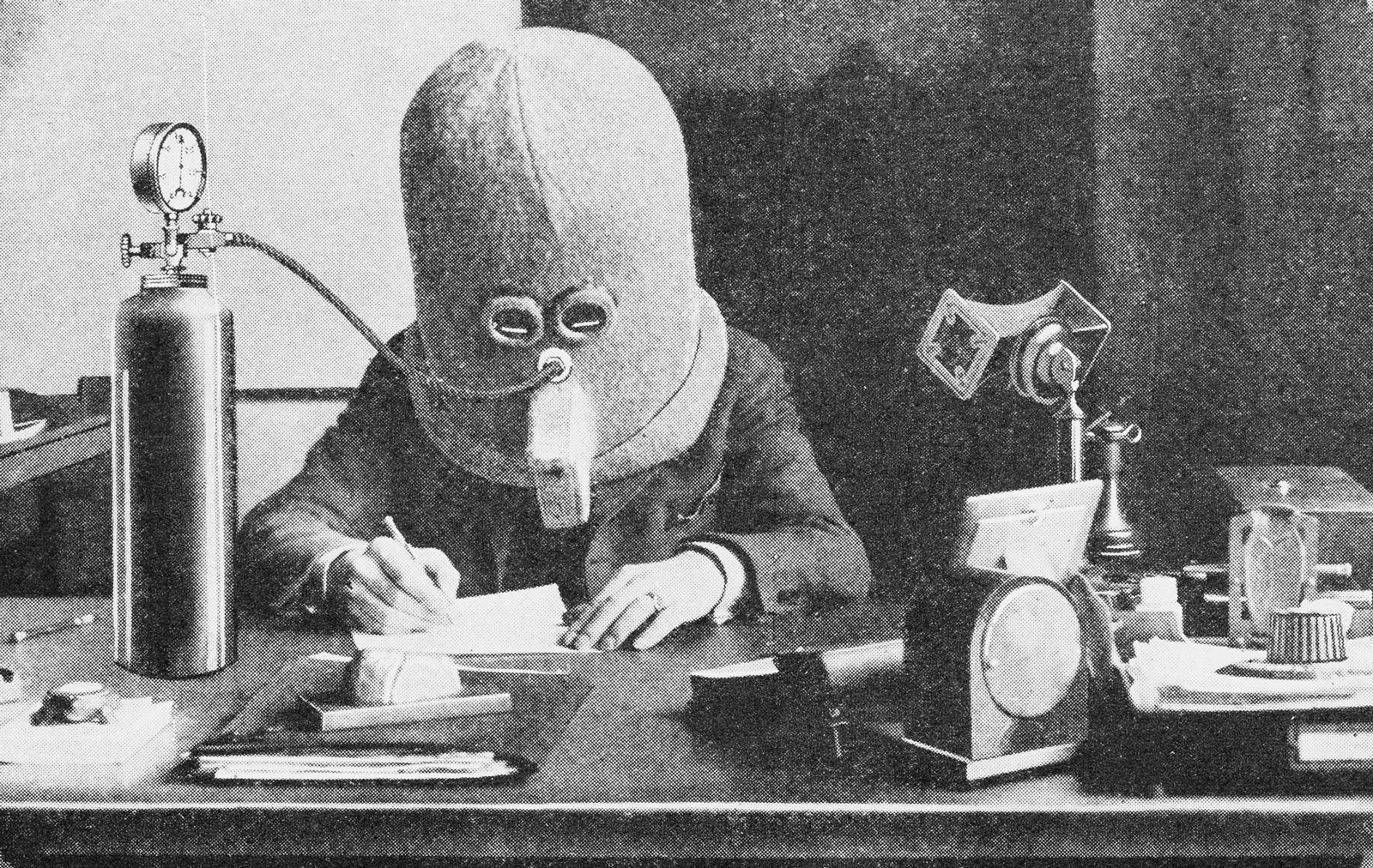

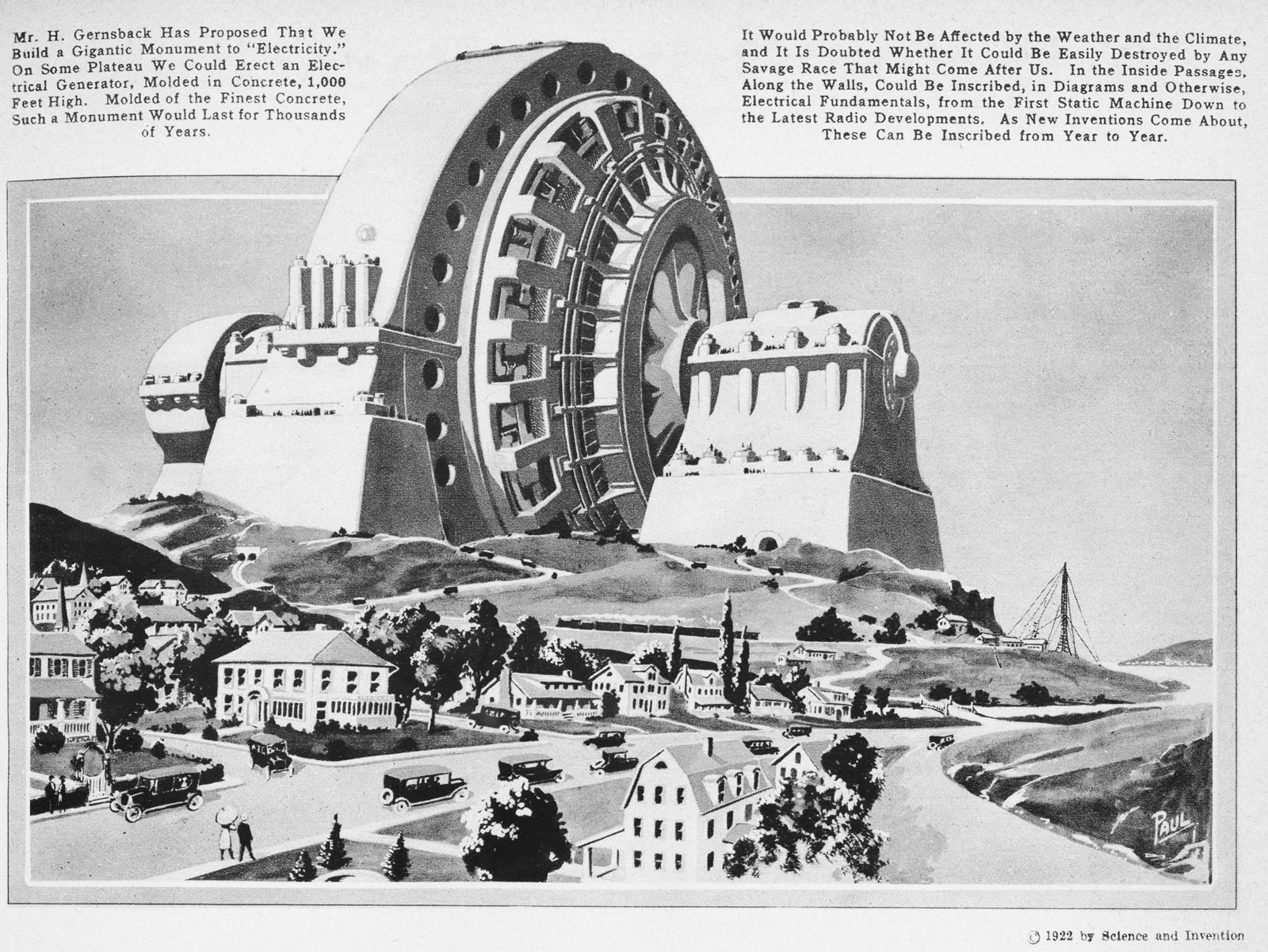

For him, imagination and prophecy were one and the same. If he could imagine a future of marvels and wonders, they were sure to arrive sooner or later. He broadcast his visions on WRNY, and the New York Times considered him an authority. “Science will find ways to transmit tons of coal by radio, facilitate foot traffic by electrically-propelled roller skates, save electric current by cold light and grow and harvest crops electrically, according to a forecast of the next fifty years made by Hugo Gernsback,” the paper reported in 1926. “We may soon expect fantastic towers piercing the sky and giving off weird purple glows when energized.” Antigravity. Floating cities. Flying men with power rays. He promised all these in the pages of Science and Invention. And more:

The future man will also be in touch with his friends or his office, or whatever it may be called then, by means of radio. He will be able to converse with them just as he can today in a more modest manner….

We admit that all of this sounds extremely fantastic, but the truths of tomorrow will surpass our wildest fiction.

The Perversity of Things: Hugo Gernsback on Media, Tinkering, and Scientifiction, edited by Grant Wythoff, is published by the University of Minnesota Press.