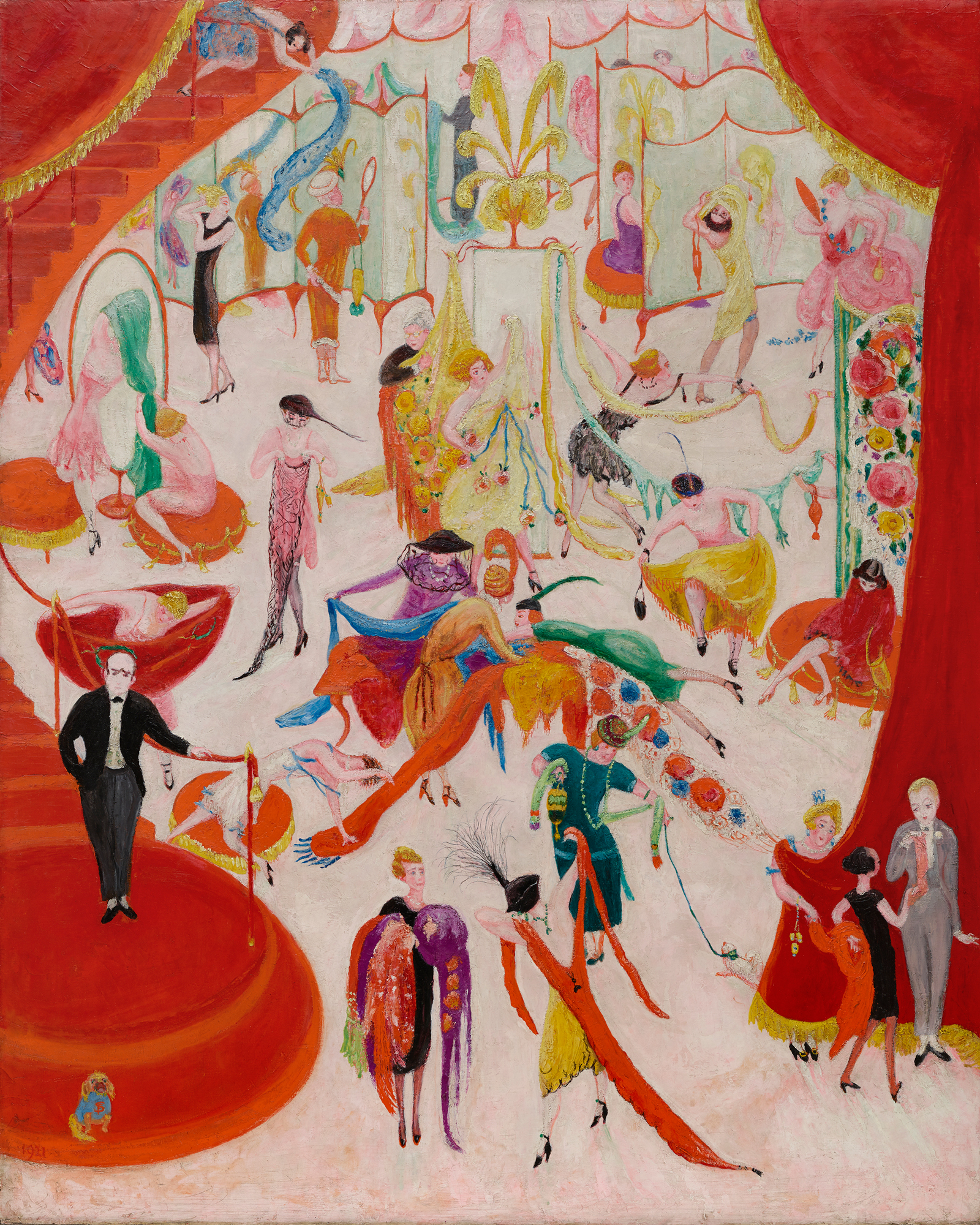

The antic Jazz Age canvases of the painter, poet, and theatrical designer Florine Stettheimer (1871-1944) can give the impression, at first glance, of a never-ending party. Through her closely observant work, we are granted entrée to exclusive birthday celebrations (with her pals Marcel Duchamp and Alfred Stieglitz recognizably in attendance), Fourth of July fireworks over Manhattan, and a frenzied spring sale at Bendel’s, though it might as well be Bruegel’s. Her signature filigrees of paint, especially red (associated at the time with the Ballets-Russes, for which Stettheimer dreamed of designing costumes, as well as with the Russian Revolution) and layer-cake-icing white, add a frothy dynamism to the festivities.

Despite the apparent frivolity of her subjects, Stettheimer—represented by over fifty paintings, drawings, and theatrical designs in an elegant show at New York’s Jewish Museum—was an ambitious, deadly serious artist who has never gotten the attention she deserves. Her varied, probing self-portraits—palette in hand and red shoes on her feet, accompanied by a Nijinsky-ish faun; or floating in space on a magical red cape, like some exotic deity; or reclining in the nude, à la Olympia—convey a sophisticated self-awareness of the confining assumptions facing a hardworking woman artist between the wars.

“Our Parties/Our Picnics/Our Banquets/Our Friends/Have at last—a raison d’être/Seen in color and design,” she wrote in one of her seemingly artless poems. “It amuses me/To recreate them/To paint them.” In Picnic at Bedford Hills, Duchamp tends the lobster pot while the sculptor Elie Nadelman chats up Stettheimer’s dozing sister, Ettie. The deceptively loopy atmosphere—suggesting Raoul Dufy with a smattering of Saul Steinberg—recalls those increasingly dreamlike party scenes from The Great Gatsby: “The moon had risen higher, and floating in the Sound was a triangle of silver scales, trembling a little to the stiff, tinny drip of the banjoes on the lawn.”

Stettheimer’s first one-person show, at the fashionable Knoedler gallery in 1916, was a flop; she turned down, haughtily or fearfully, Stieglitz’s generous offer of an exhibition in his own avant-garde gallery, An American Place, which had promoted his partner Georgia O’Keeffe’s work. Stettheimer’s “openings,” thereafter, were in the safer confines of the luxurious rooms in the ornate building a block north of Carnegie Hall—dubbed “Chateau Stettheimer” by her close friend the photographer, writer, and jazz aficionado Carl Van Vechten—where she lived with her mother and two of her sisters, unmarried like her, and showed off her new paintings one by one. Studio Party (Soireé) (1917-1919) documents one such occasion; while the guests are recognizable, the painting they are admiring so intently is modestly, self-effacingly, hidden. Though Stettheimer over the years would allow a painting or two to appear in group exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art or the Whitney, she lamented to a friend in 1932 that she would “never be rescued from oblivion!”

“Art is spelled with a capital A,” Stettheimer wrote in another of her beguiling, Dada-inspired (and, like her art, underappreciated) poems, “And capital always backs it.” She added, with an incisive pun, “Ignorance also makes it sway.” Capital certainly backed Stettheimer, though it remains unclear to what degree her inherited wealth sustained her career or inhibited it. Commentators have groped for the right phrase to describe her double status as (rich, well-connected) insider and (self-consciously Jewish, female) outsider. She was an “haute outsider,” according to the artist Jutta Koether, a “Rococo subversive,” in the view of feminist art historian Linda Nochlin.

Born in Rochester, New York, Stettheimer was descended from two German-Jewish banking fortunes. When her father, Joseph Stettheimer, deserted the family, Stettheimer’s mother, Rosetta Walter, used her Walter inheritance to take her five children to Europe in 1906. As a teenager, Florine took drawing lessons in Stuttgart and Berlin, producing masterly drawings, some of which are on view in the current show, and frequented museums in Munich, Paris, and Italy. Returning to New York at the outbreak of World War I, Florine (like Henry James in The American Scene) adopted something of an immigrant’s wide-eyed perspective on her home town; the flamboyant, newly erected Chrysler Building, which she painted in the background of one of her family portraits, “always seems as though it might itself have been a Stettheimer creation,” noted one of her friends.

Stettheimer’s exuberant take on New York spectacles “truly lifts the pall from life,” as the poet Marianne Moore once told her. These circus-like stagings of urban life culminated in her four Cathedral paintings, completed between 1929 and 1942 and devoted to Wall Street, Broadway, Fifth Avenue, and the New York art world.

Advertisement

Her 1924 Beauty Contest: To the Memory of P. T. Barnum is a boisterous framing—literally, with a handmade gilded frame of her own—of a ritual that struck Stettheimer, at the same time, as faintly ominous. Uniformed judges inspect fey, lily-white Miss Atlantic City while an African-American jazz band, the real source of vitality in the scene, performs on a red and gold stage. Edward Steichen aims his camera from an upper corner, documenting the cheerful, awful proceedings in parallel with Stettheimer herself. “Beauty contests,” she wrote in her diary, “are a B.L.O.T. on American something—I believe life—or civilization.”

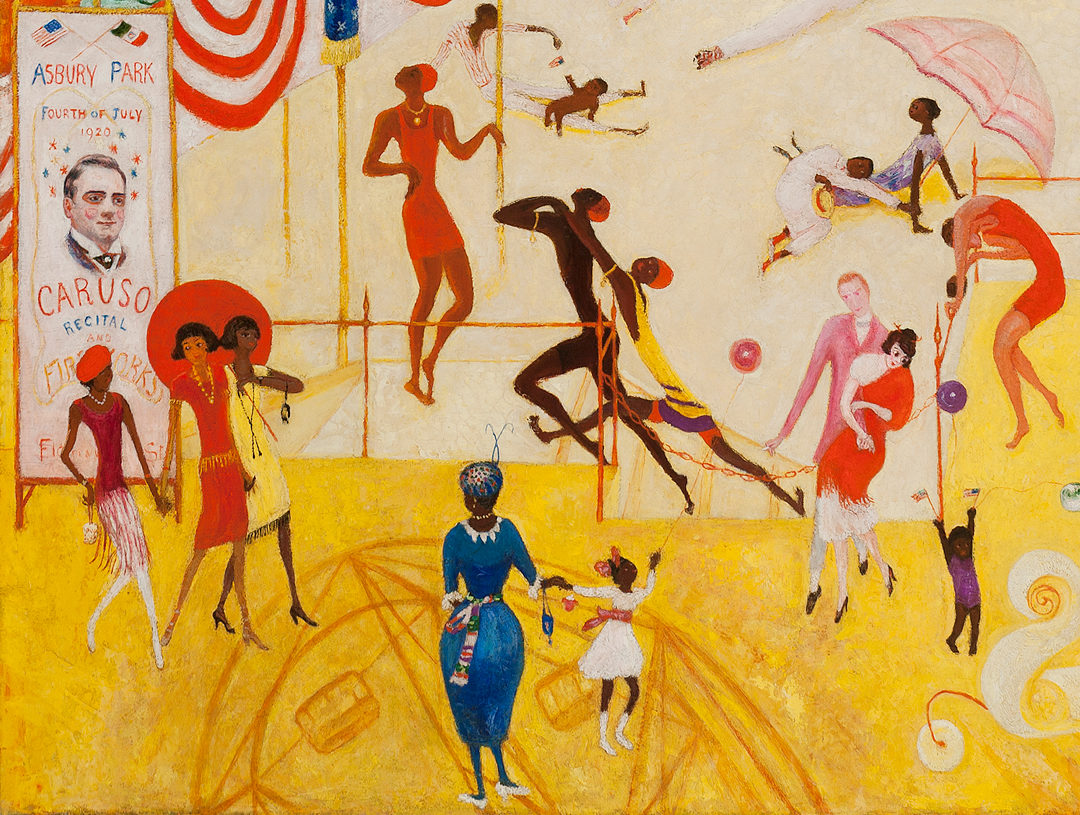

Many of Stettheimer’s closest friends—Nadelman, Stieglitz, and Duchamp, who tutored the Stettheimer sisters in French and flirted with them—were immigrants; they appear in her paintings as spectators, voyeurs, haute outsiders like her. She and her artist friends were sympathetic to the less fortunate outsiders in their midst. In Asbury Park South (1920, deaccessioned by Fisk University a few years ago, in a controversial sale that only recently came to light), Van Vechten and his Odessa-born actress wife, Fania Marinoff, stare down from a reviewing stand at the segregated beach below, while Duchamp strolls through the throng. The African-American denizens assume both the stylized poses of Josephine Baker and the less stereotypical postures of ordinary people out for a stroll on the beach. In her greatest public success as an artist, Stettheimer designed the costumes and scenery for the 1934 production of Four Saints in Three Acts, in which an all-black cast performed Virgil Thomson’s avant-garde opera with its libretto by Gertrude Stein. Her handmade figurines for planning the production, decked in cellophane and feathers, have a Calder-like ingenuity and panache.

Two of the strangest paintings in the show portray Duchamp, who had created a stir in New York with his abstract Nude Descending a Staircase and his very concrete Fountain (an industrially produced urinal). In one painting, a perfect square, Duchamp’s androgynous, saint-like face radiates out from a heavily painted, off-white background. Based on a Symbolist portrait of Jesus’s face appearing on the Veil of Veronica, is this painting meant seriously—Duchamp, as has been suggested, as the redeemer of Modern Art—or is it played for laughs? Similar questions surround her weird 1923 portrait, framed by a metallic doubling of the letters MDMD, of Duchamp seated in an armchair, seemingly ice-fishing.

He’s actually turning the crank of a little machine that summons up his female alter-ego, Rrose Sélavy (possibly based, it has been suggested, on the Stettheimer sisters), who appears, genie-like, at the top of a spring-supported stool. The painting is accompanied by Stettheimer’s mysterious, Stein-like love poem, “Duche,” about the “love flight” of a “silver-tin thin spiral”—presumably the sex-change apparatus in the painting. Such gender-blurring aspects of Stettheimer’s work are not lost on recent commentators. “Both the male and female protagonists in the paintings are androgynous,” the artist Silke Otto-Knapp notes, in a conversation reproduced in the exhibition catalog. Jutta Koether goes farther, “Her work is queer, even trans, in every respect… I like that she obsessively took on Duchamp as her muse.”

There is a larger cultural dimension to much of what we see in Stettheimer’s paintings: the skyscrapers, the department stores, the African-American jazz, the shifting gender roles. Viewers in search of the perfect counterpoint to the Stettheimer retrospective need only walk a block south to the razzle-dazzle show “The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s,” occupying two floors, through August, at the Cooper-Hewitt. Take Stettheimer’s spring sale at Bendel’s, for example. “While shopping,” according to the informative catalog for the Cooper-Hewitt show, “Americans experienced modernism not only through the garments and accessories on display but also through the retail environments themselves,” with Cubist-inspired mannequins and rug patterns. In “The Jazz Age” you can see, close up, the corset-free Coco Chanel dresses the female partygoers wear in Stettheimer’s paintings; their chic cigarette holders and African-themed giraffe bracelets; the sleek divans they lounge on in the moonlight in Stettheimer’s Heat (1919); even the cars that took them uptown to Harlem for some fashionable slumming. Young women, according to the catalog, were given to “jumping headlong into the whirl of commerce by day and all manner of vice by night, flapping their wings like butterflies and thus giving meaning to the term ‘flapper.’”

Advertisement

Prohibition, paradoxically, meant that much was permitted as long as it was tastefully concealed. It’s fun to see a silver cocktail shaker disguised as a high-end sculpture of an owl; turn this night owl’s head and let the party begin. Eleanor Roosevelt, when she was the wife of the New York governor, commissioned a jazz-themed punchbowl with inscribed motifs of skyscrapers and musical notes. Its cobalt-blue glaze—in the same tonal register as the New York dusk in Stettheimer’s Family Portrait II—was meant to evoke the new “funny blue light” of neon. Archibald Motley Jr.’s Blues gives a sense of the free and easy mood of the integrated dance-floor in a Paris jazz dive.

A challenge for the catalog contributors is to define the elusive word at the heart of the exhibition. “The word jazz in its progress toward respectability,” F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote with cavalier historicity, “has meant first sex, then dancing, then music. It is associated with a state of nervous stimulation, not unlike that of big cities behind the lines of a war.” And behind the color line, he might have added. But the audacious, improvisatory energies unleashed by jazz in all its manifestations did indeed take over American culture during the Jazz Age. Circling back to the Stettheimer show, we can see, more precisely, what Van Vechten, who knew more about jazz than almost any of his white contemporaries, meant in one of his remarks about his friend’s work. “This lady has got into her painting a very modern quality,” he observed, “the quality that ambitious American musicians will have to get into their compositions before anyone will listen to them. At the risk of being misunderstood, I must call this quality jazz.”

“Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry” is at the Jewish Museum through September 24, and will be on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario from October 21 through January 28, 2018. The catalog, edited by Stephen Brown and Georgiana Uhlyarik, is published by Yale University Press in association with the Jewish Museum and the Art Gallery of Ontario.

“The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s” is at the Cooper-Hewitt Museum through August 20, and will be on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art from September 30 through January 14, 2018. The catalog, edited by Stephen Harrison and Sarah D. Coffin, is published by the Cleveland Museum of Art and distributed by Yale University Press.