Although Raphael for much of the last five hundred years has been celebrated as a prince of painters, today he is often dismissed as no more than a kind of chief courtier: supreme in grace and rhetoric, yet mannered and unnatural, even insincere. The current disregard for him arises not just from the stark change of taste in modern art, but also from the severe difficulties in seeing his works as they were meant to appear. Many of his pictures have been over-restored, thereby amplifying their unearthliness; others are products of his large and prolific workshop; and his greatest masterpieces, including the School of Athens and the Transfiguration, are at the Vatican and can only be seen among rushing mobs of tourists. Those sublime paintings are familiar to us primarily from photographs in books, which are wholly inadequate in conveying the pictures’ subtlety, detail, and scale. (The illustrations of the School of Athens in the standard monographs on the artist are less than 1/1,000 of the size of the original.) Raphael seems so abstract and remote, because we have so little direct contact with him.

“Raphael: The Drawings,” on view at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, until September 3, provides a rare chance to see up close a wide array of the artist’s works from throughout his life, and the effect is thrilling and revelatory. Bringing together 120 sheets, almost one-quarter of his extant drawings, it is the largest assembly of the artist’s works in one place since the unforgettable show of his drawings at the British Museum in 1983. Not only can you see here his astonishing virtuosity in handling every Renaissance drawing technique, from metal point to pen and ink and black and red chalk; more importantly, you can watch him work with fierce concentration and explosive creativity as he seeks to design his compositions and capture the actions and emotions of the figures he portrays. The vivacity and immediacy of the images is so strong they seem to spring to life right before your eyes. You come away from this dazzling show with a much firmer grasp of the artist, one that enables you to understand better why every later painter in Western art, from Rubens and Rembrandt to Ingres and Picasso, saw him as an absolute master of their field, and among the greatest draughtsmen of all time.

For viewers today, one surprise of the drawings is their unwavering focus on emotional intensity. This quality in Raphael’s work has not always been easy to recognize, given the bland paintings of the Madonna and saints he produced in his youth, and his frequent reliance on shop assistants in making his frescoes and altarpieces during his maturity. But the drawings show that throughout his career, from his start as a precocious teenager in provincial Umbria until his death at thirty-seven in 1520 when he was the most celebrated painter in Rome, he sought to portray the interior life of thought and feeling, and to do so with ever greater accuracy and power.

Even the earliest drawings in the show are wonders of tenderness and sensibility. One sheet, drawn around 1503 when Raphael was only twenty years old, is a study in black chalk of the head of a young apostle (usually identified as Saint James) in the Coronation of the Virgin, an altarpiece made for a church in Perugia but now in the Vatican museum. In the painting he stands by the tomb of the Virgin, and stares above rapturously as in the sky overhead Jesus crowns Mary the queen of heaven. All the lines in the drawing seem to surge with excitement and shoot upward in the direction of his gaze. The ecstasy of revelation is conveyed as well by the softness of his parted lips, the sheen of his radiant eyes, and the tumult of his curls dancing around his head. Even the soft lines of black chalk making up the shadows on his neck appear to dash about with spirited impetuosity. Raphael’s father, the painter Giovanni Santi, wrote in a poem that drawings should have the quality of moventia—movement. Raphael’s own drawings overflow with expressive energy.

It is instructive to compare this sheet with the corresponding head in the altarpiece. There the saint’s face appears much calmer and more remote; indeed, its emotional content is hard to discern, except in light of the preparatory drawing. It is an odd contrast: every line in the drawing seems calculated to heighten the sense of motion and emotion; and then in the painting this very liveliness is suppressed and made subservient to other, notionally loftier, goals. Raphael in his youth, it seems, believed that emotion was necessary but potentially indecorous in his completed paintings, where above all he sought a kind of platonic ideality, drained of earthliness and humanity.

Advertisement

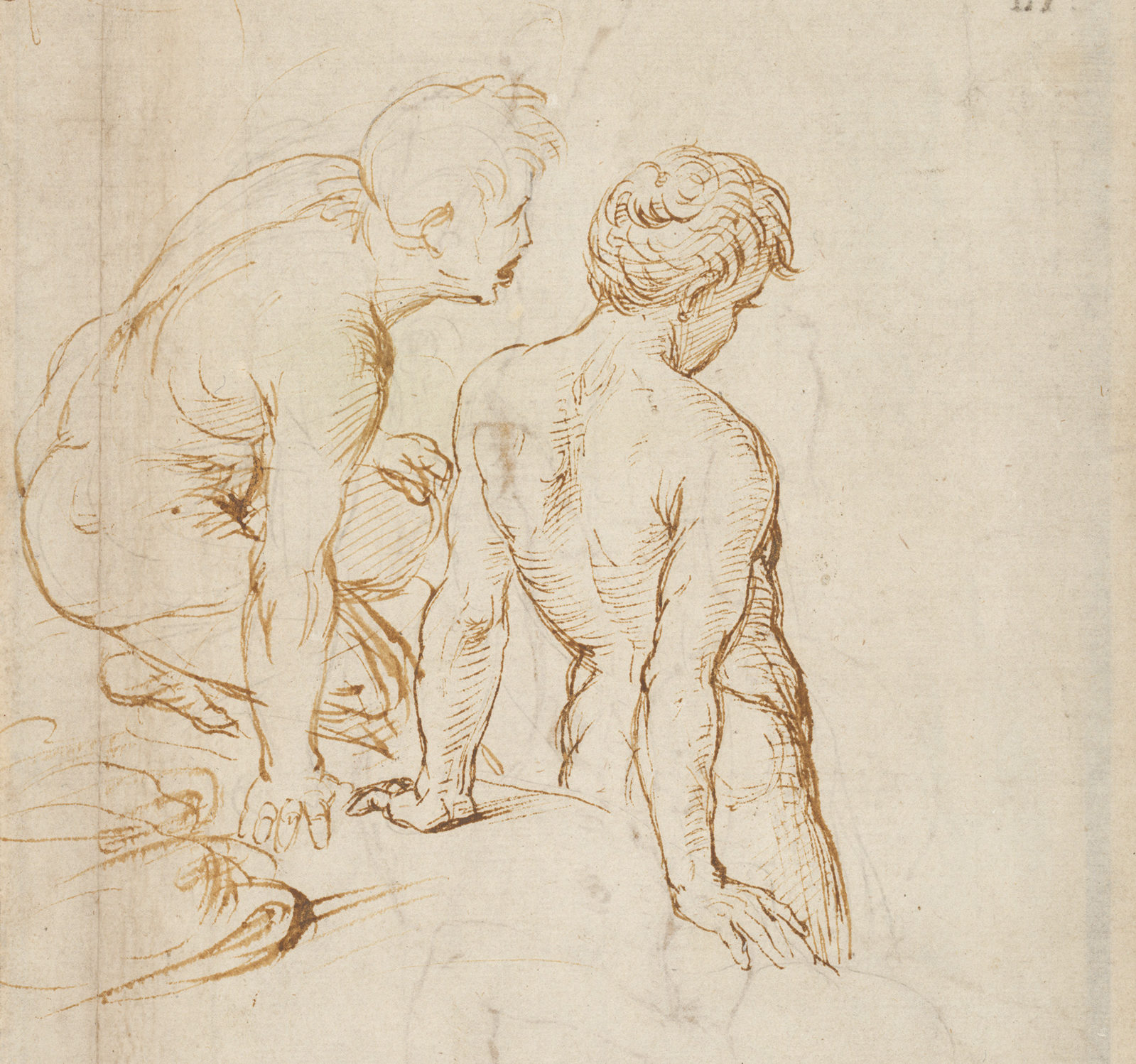

Raphael’s pursuit of emotional power accelerated rapidly following his move to Florence, probably at the end of 1504. He arrived at a heady moment. Michelangelo had just installed the David in the Piazza della Signoria and was feverishly working on both a series of revolutionary sculptures of the apostles for the Duomo, and the colossal painting of the Battle of Cascina for the Palazzo Vecchio; and in direct competition with him, Leonardo was creating a gigantic fresco of the Battle of Anghiari for the same room in the Palazzo. The exquisitely rendered heroic naked men in Michelangelo’s picture, and the violent clash and fury of Leonardo’s, were unlike anything seen before. Raphael’s direct study of these masters’ works is made clear in the Ashmolean exhibition by one drawing after Michelangelo’s angular and masculine David and another after Leonardo’s sinuous and sexy Leda and the Swan. His new level of mastery is particularly evident in a pen and ink sketch, inspired by the Battle of Cascina, showing a young nude man lowering himself into a river or pool of water. The sense of actuality is so strong in this drawing that the viewer can feel in his own body exactly what is being depicted: the arch of the back, the pressure on the hands and arms supporting the upper torso, the coolness of the water on the thighs slipping into the stream.

The power to compel recognition, to force us to feel what the figures portrayed are feeling, is the secret to Raphael’s triumph after he moved to Rome in 1508 and started work on the Stanze, the private chambers of Pope Julius II. Throughout his biography of Raphael, first published in 1550 and revised in 1568, Giorgio Vasari singles out this quality for special praise. For example, in his account of The Mass at Bolsena, which the artist painted between 1512 and 1514 for the Stanza di Eliodoro, Vasari vividly describes the emotional turmoil of the priest who had doubted the reality of transubstantiation until the sacramental wafer he holds in his hands begins miraculously to bleed. Vasari writes,

In this scene one sees in the face of the priest who is saying Mass, which is glowing with a blush, the shame that he felt on seeing the Host turned into blood on the Corporal on account of his unbelief. With terror in his eyes, dumbfounded and beside himself in the presence of his audience, he seems like someone who knows not what to do; and one recognizes in the gesture of his hands the tremble of fear that one would have in similar instances.

For Vasari, as for other viewers of the time, Raphael was unsurpassed in the truthful and penetrating depiction of emotion. The complexity and subtlety of Raphael’s rendering of expression is largely ungraspable in photographic reproduction. Looking at illustrations in books or on the Internet, you cannot fully see what Vasari and so many others admired about his work. But gazing upon his drawings in the Ashmolean exhibition, his power to capture emotion comes forth with the utmost immediacy.

The great care that Raphael took to dramatize the passions of his figures is especially clear in the show in four sketches he made around 1509–1510 when designing a print of the Massacre of the Innocents, which was to be engraved by his collaborator, Marcantonio Raimondi, the master printer. A scene of climactic violence, it depicts several women desperately trying to save their infants from a band of naked thugs who slash and stab at them. Raphael studied every detail of every gesture and expression until he found exactly the effects he wanted. For example, in one study in red chalk of a woman fleeing a killer he emphasizes the motion of the mother’s arms as she grasps her baby protectively to her chest, and in another composition in pen and ink he instead pays greater attention to the terror displayed by her weeping eyes and gaping mouth. The drawings allow us to see as well how Raphael combined all these elements into a complex whole that enabled long and attentive viewing. Unlike many modern paintings, which are too often designed to be consumed in a flash, Raphael’s studies of the Massacre of the Innocents contain numerous separate details of gestures and expression, full of pathos and strife, and meant to be savored in the course of sustained contemplation.

Advertisement

Near the center of the print stands an abandoned child, alone and weeping. It is remarkable how often Raphael returns to the theme of an unsettled youth, desperate for parental love and protection. Many of the Madonna drawings depict a child anxiously grasping for the mother, and one image of Charity shows a boy standing at her side and tugging on her arm both to get her attention and to prevent her from giving suck to another baby on her lap. How odd too that his first major narrative painting, the Entombment of Christ in the Borghese, made around 1507, was commissioned by a mother, Atalanta Baglioni, to commemorate her dead son, whom during a family feud she had refused refuge to, thereby condemning him to be killed; or that in his last picture Raphael broke with tradition in images of the Transfiguration and added the subsequent scene in the Bible in which a father begs the apostles to help his only son, who is in the grip of demonic possession. We shall never know if Raphael’s own experiences as an orphan—his mother died when he was eight and his father when he was eleven—informed his sympathy in the depiction of such subjects. It is nonetheless testimony to the consummate emotional force of the drawings that they seem so deeply personal.

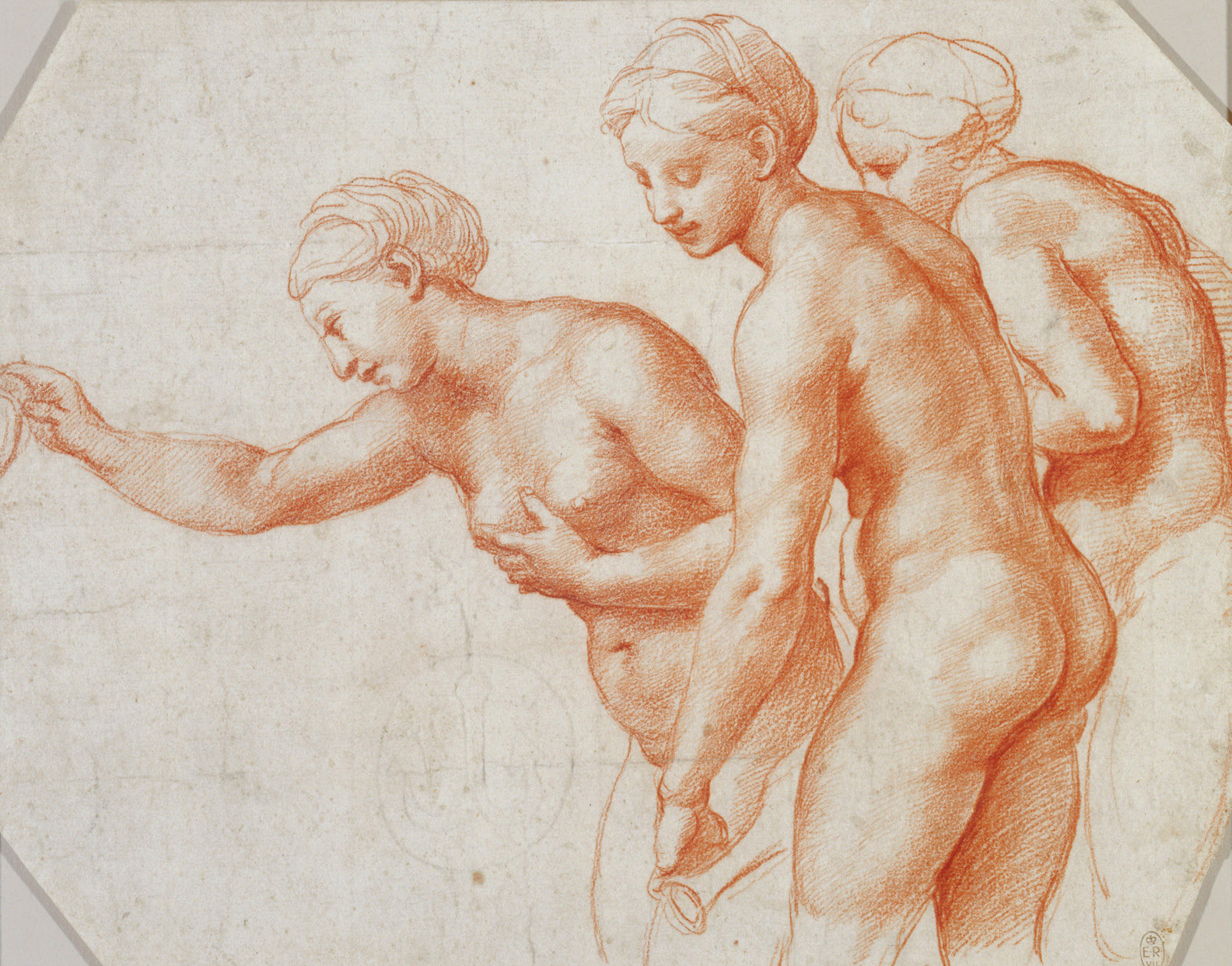

Another feature of Raphael’s drawings on glorious display in the exhibition is their sumptuous sensuality. From the start of his career, he made light falling on skin seem to caress it tenderly, and the eyes of his figures, whether male or female, often have a languorous, come-hither appeal. The voluptuousness of his drawings became more forthright as he matured, until he achieved a frank depiction of sexual allure, unlike anything made before in post-classical art. The show presents four chalk sketches of nude nubile women he drew around 1517–1518 as preparatory studies for frescoes in the loggia of Agostino Chigi’s Villa Farnesina. The forms of the youths are soft and luscious and the red chalk gives them an ardent rosy flush. One drawing is particularly vivid in its description of the woman’s sexual desirability. It depicts in profile a nude who is kneeling and raising one arm. Although predominantly in red chalk, as the catalog notes, it has “touches of black chalk,” which Raphael has added for emphasis and blended in with the red at just three points: her armpit, her right nipple, and especially, her pubic hair, which has an enticing warm dark glow. Vasari reports that when Raphael was supposed to make the fresco in the loggia, he was too inflamed with love for a girl to work, until Chigi brought her to live at the villa so that Raphael could see her between painting sessions. It is easy to imagine that these drawings reflect the heat of that passion.

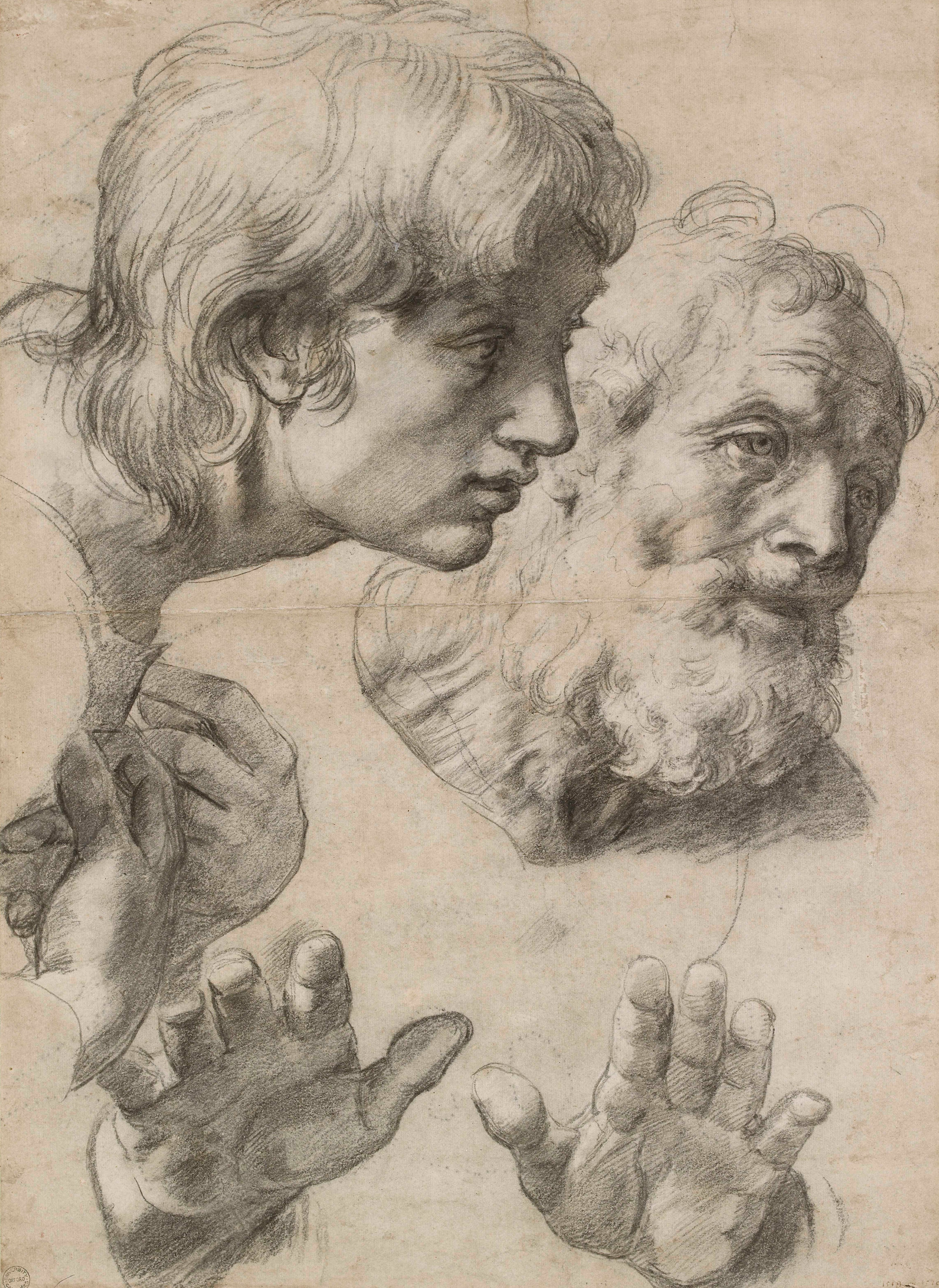

The show concludes with The Heads and Hands of Two Apostles (1519–1520), a study for the figures at the center of the lower tier of the Transfiguration, the magnificent altarpiece on which Raphael was working at the time of his death. The lower portion of the painting shows the apostles reacting with loving concern to the boy possessed by a demon. Vasari specially praises Raphael’s depiction of the grandissima compassione—the very great compassion—of the apostles. This is not a standard turn of phrase in Vasari; indeed it is the only time in all the Lives of the Artists that he uses this combination of words. The drawing shows just two apostles, one young and one old, in slightly different states of response. At the left, the younger of the two leans forward, his tender eyes fixed in a stare, and he holds his hands up to his chest in a gesture of profound emotion. At the right, utterly captivated, the older one also bends forward, gazing in surprise; and the veins in his neck pulse with tension and excitement. But rather than turning toward himself, his soft hands at the bottom of the image reach out toward the viewer. In this fabulous sheet, perhaps one of the greatest drawings in the world, Raphael has reduced art to its very essence: seeing and feeling.

“Raphael: The Drawings” is on view at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum through September 3.