Though the collapse of the seven-year Republican effort to kill off the Affordable Care Act came in one of the most dramatic moments in US Senate history, deeper currents had been running against the Republicans’ serial attempts to repeal Obamacare. The failure was a testament to what can happen when the party taking control of the government seeks to overturn a major advance by the prior administration without any coherent idea of what it will do instead. In their determination to repeal a law greatly expanding the federal government’s commitment to help people obtain decent health care, the Republicans had gotten out of touch with the opinion of the people.

The Republicans had pledged to repeal the Affordable Care Act from the moment it was signed into law by Barack Obama in March 2010, and they’d voted again and again to get rid of it—when it didn’t count, since Obama was president and had a veto. But when a Republican—one who had promised to undo the ACA—won the presidency, with both the Senate and the House also in Republican hands, Congress had to deliver. In trying to muscle through a momentous change in the law in ways that would affect tens of millions of people, Republican leaders disregarded the norms of democratic lawmaking. As the August recess beckoned and amid some particularly odd legislative proceedings, the Senate voted down a series of proposals to severely cut back on what had been given to the people seven years before. In the end, the ailing John McCain cast the deciding vote and, along with two other Republicans and a united Democratic Party, delivered a colossal blow to President Trump.

Trump badly needed a victory. Six months into his presidency he hasn’t had a single major legislative achievement. Other Trump priorities—revising the tax code, raising the debt ceiling, passing a budget—have lingered while the health care bill preoccupied Congress. Trump’s infrastructure program, such as it was, has more or less disappeared, despite the administration’s “Infrastructure Week” in early June, which was largely overtaken by fired FBI director James Comey’s testimony on Capitol Hill. Trump’s White House has been a shambles, with its internal warfare increasingly spilling into open ferocity. Moreover, the FBI investigation into his and his campaign’s dealings with Russia in connection with the 2016 election is growing more menacing; the noose is tightening. The distracted president has been hurling insults at his attorney general and hatching plots to get rid of the investigation—a highly dangerous thing for him to try to do.

Numerous critics have said that the White House was unwise to begin its congressional efforts on such a divisive issue as health care. But the Republicans had promised to repeal Obamacare in election after election; no issue has been more useful in stirring up their base. Trump himself had promised to begin his presidency with repeal. Republican congressional leaders also needed the repeal of taxes on the wealthy that would be part of their proposals to cripple Obamacare so that they could use that money to cut taxes later in what they have chosen to call “tax reform.” The tax cuts to be proposed in that bill mattered most to the Republican leaders, in particular House Speaker Paul Ryan, who though he had a shaky relationship with Trump—or perhaps because of it—would exercise great influence on the policies of the new president.

The Republicans’ implacable determination to put an end to Obama’s proudest legislative achievement has had to do with disdain for our first black president as well as resistance to such an expansion of government. Thus “Obamacare” was intended as a derogatory nickname. But they didn’t reckon on two things: that the program would become popular once a large number of people signed on to it; and that after two terms Obama would end up one of our most liked presidents.

The Republicans are particularly adept at injecting truisms into the ethos that aren’t true. One example is their insistence that Obamacare had been “rushed through Congress,” had been “shoved down our throats.” In fact, the passage of the bill came after more than a year of deliberation and was the subject of dozens of hearings in both houses and lengthy consideration in several committees. Republicans also complained that the ACA had been passed on a “partisan” basis but that was because Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell had insisted that Republicans not compromise with the Democrats or put their imprimatur on the bill. This was of a piece with the leadership’s overall strategy of opposing every Obama proposal. (McConnell, who rarely does so, slipped and said that his intent was that Obama be “a one-term president.”)

Advertisement

Over time it became clear that flat-out opposition to the ACA was leaving a great part of the public dissatisfied: too many people were enjoying its benefits. If Republicans were to continue to call for repeal, they had to at least appear to intend to offer some sort of substitute. So the party’s rhetoric shifted. The new motto was “repeal and replace” and we no longer heard about “government control of your health care.”

At a rally in February 2016, Trump promised, “Obamacare is going to be repealed and replaced. You’re going to end up with great health care for a fraction of the cost and that’s gonna take place immediately after we go in. Okay? Immediately. Fast. Quick.” The following month, he pledged on his website: “On day one of the Trump Administration, we will ask Congress to immediately deliver a full repeal of Obamacare.” (This was later deleted.) According to one count, Trump promised to repeal and replace Obamacare at least sixty-eight times, often pledging that action would commence on that poor, overworked day one. It has bothered Trump mightily that Obama was far more popular and had achieved a great deal more at this point in his presidency than Trump has. Trump’s aides have tried to cheer him up by telling him he’s doing great, and it’s possible he believes them. Trump creates his own realities. In June, he claimed, “Never has there been a president, with few exceptions—case of FDR, he had a major Depression to handle—who has passed more legislation and who has done more things than what we’ve done.” Such statements are of a piece with Trump’s supposed larger inauguration audience than Obama’s and his miscount of the number of times he’s been on the cover of Time. The extravagant hyperbole obviously fills a need on Trump’s part.

One lesson of the Republicans’ entanglement with health care is that you can’t legislate a slogan. For nearly seven years, the Republicans appealed to their base by promising to get rid of the ACA and thereby raising money from unsuspecting followers. Now they needed a new line of attack. They simply declared Obamacare a failure. This has taken various forms—the program is in a “death spiral”; or this or that county doesn’t have any insurance companies who want to participate in its health care exchange. Trump himself routinely deemed the ACA “dead.” The problem with the Republicans’ arguments, as Ezra Klein pointed out in a searing article in Vox in March, is that they weren’t true. For example, the respected Kaiser Family Foundation has reported that all of thirty-eight counties out of 3,143 nationwide—around 1 percent—are at risk of starting out in 2018 without health care exchanges for lack of participants.

The Republicans had trapped themselves. Despite various promises, beginning with Trump’s announcement during the transition that his own health care plan would be ready any day now, he failed to come up with one, and so it fell to the Republican leaders of each chamber to provide it. When in March a House bill that had White House backing had to be pulled from the House floor for lack of votes, Trump maintained, “I never said ‘repeal it and replace it within 64 days.’ I have a long time. But I want to have a great health care bill and plan—and we will and it will happen.”

With 20 million people having signed up for Obamacare, and numerous governors favoring the program, especially its expansion of Medicaid, the Republican leaders’ proposals stopped short of completely eliminating the 2010 law. Nonetheless, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the House-passed bill would cut off health care coverage to 23 million people over the next ten years, and a bill drawn up under McConnell for the Senate to consider would do so for 22 million. The greatest outrage was stirred by the provisions of both bills for deep cuts in Medicaid to make up for a repeal of taxes on the wealthy. This proposed transfer of benefits from the poor to the rich plus the threatened cutoff of coverage to many millions of people had numerous Republican members of Congress hiding from their constituents during recesses.

Fearful of the public reaction to their proposals, and not wanting to allow groups time to mobilize against them, Speaker Ryan and Senate Majority Leader McConnell most unusually drafted the bills in secret and tried to rush them to a vote in both the House and Senate. No committee hearings, no airing of the proposals to see how they stood up to criticism and challenge; the very committee system by which Congress normally functions was deemed irrelevant. The departures from standard legislative process not only failed to prevent vigorous protests; if anything, with some organizing groups on watch, the protests grew stronger. There was widespread fear that benefits people had come to depend on would be taken away—including benefits for the elderly, pregnant women, people with disabilities or needing nursing home care, all of which were enacted in Medicaid and Medicare legislation in 1965 and expanded by the ACA. The House and Senate bills had won the approval, respectively, of 12 and 17 percent of the electorate.

Advertisement

And then an unexpected thing happened: in June, a Kaiser Foundation poll found that for the first time a majority of Americans—51 percent—supported Obamacare. Additionally, according to the poll, a majority opposed deep cuts in Medicaid. More than seventy million Americans are helped by a combination of Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which was passed with strong bipartisan support during the Bill Clinton administration after its hopelessly complicated health insurance program collapsed in the Congress. The rapid growth of Medicaid made the program a target for conservatives. In March of this year, after the Republican-controlled House passed a bill with huge cuts in Medicaid, a jubilant Paul Ryan, a supposed budget guru, told National Review editor Rich Lowry, “We’ve been dreaming of this…since you and I were drinking out of kegs.”

The Republicans’ insistence on “killing” the ACA (even though their proposals didn’t completely do that) made it impossible for Democrats to negotiate with them. Republicans hypocritically complained that the Democrats wouldn’t “come to the table”; but there was no table. Loose talk by political observers and commentators about how nice it would be if the two parties worked toward a bipartisan solution neglected this basic reality. It’s not that Democrats have been blind to certain problems in the ACA; for example, premiums have risen more than people had expected, shoppers for coverage are finding fewer options. Some of the issues arise from the premises behind the law’s initial design. Obama wanted to get a bill through Congress and he deemed the political system not ready to absorb one of two alternatives: government-provided health insurance (the “public option”), or a form of Medicare coverage for everyone, which was backed by the late Edward Kennedy (a “single payer” plan). President Obama at first proposed offering people the alternative of a public option where the insurance exchanges were weak, or as an incentive to get them to work better, but dropped it under pressure from the insurance industry. Similarly, to keep the drug companies—organized in a powerful PHARMA lobby—from fighting the Obama plan, the White House agreed not to demand that they negotiate their drugs’ prices with the federal government or to allow the import of less expensive medications from Canada. These concessions created certain realities—in particular outrageous prices for medications, or higher increases in insurance premiums—for which the ACA is blamed.

Numerous proposals have been floating around to fix some of these problems, and it’s likely that the next great health care debates will be about alternative ways to provide government assistance for health care. But as long as one side insists that the ACA must be eliminated—until they drop the pretense that that’s what they’re trying to do, stop using the issue as a partisan rallying cry, and cease pushing legislative proposals to significantly dismantle it—there can be no serious attempt to address these issues.

Congress hasn’t been the only arena for the battle over the fate of Obamacare. The Trump administration has taken executive actions to try to cripple the program, and has the right personnel in place to do so: Tom Price, a former congressman who was a fierce opponent of the ACA, serving as the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, and Mick Mulvaney, a founder of the Freedom Caucus, heading the powerful Office of Management and Budget. Trump himself has sometimes suggested that the government cost-sharing fees wouldn’t be paid to the insurance companies, as a way of forcing Obamacare to collapse—but then he’d back off out of fear of getting the blame. Such threats have created uncertainty about the program’s future and frightened some insurance companies out of participating. The Trump administration recently shut down the centers in major cities that help people sign up for Obamacare and shortened by half the time to shop for coverage in 2018. Trump has said several times that he would like to “let Obamacare fail” and blame the Democrats—presumably for backing the program in the first place.

While the majority party in Congress having one of its own in the White House presumably gives it a tremendous advantage in legislative struggles Trump’s participation in the health care fight if anything made things worse. During the House debate this spring, Trump held meetings with members at the White House and tried to persuade reluctant ones, but it turned out that he was also an easy mark. (This was much noticed about Trump at the time and later it showed up in some of his foreign dealings.) Trump sometimes made offers to congressmen that mucked up the Republican leadership strategy. It was evident that the president didn’t much care what the bill contained: he just wanted to sign one. It quickly also became clear to Republican legislators that the president was unfamiliar with the details and evinced little interest in learning them. Word of this spread quickly. Trump is the least informed president in modern history.

After the House bill passed in early May, a buoyant Trump led a celebration of House Republicans, who were bussed to the White House for the event—a scene that may well turn up in Democrats’ ads in the future. (“Hey, I’m President!” the triumphant Trump exclaimed.) But soon after that he threw away a large amount of this bonhomie by saying he thought the House bill was “mean.” There’s no more effective way for a president to make his party’s politicians wary of casting any risky votes out of so-called loyalty. When in June it came time for the Senate to take up the health care legislation, McConnell asked the president to please stay out of it. With the exception of a few misfiring tweets and a White House lunch with Republican senators this suited Trump fine; aides said he’d become “bored” dealing with the legislation. Governing doesn’t interest him.

The successful passage of the House bill depended on the support of Freedom Caucus members, who were appeased by measures that, among other things, rolled back Obama’s Medicaid expansion, eliminated the mandate that provided the pillars for Obamacare, and loosened the protections for those with pre-existing conditions. The House bill went so far that a number of Senate Republicans dismissed it out of hand, thus complicating McConnell’s mission of not just passing a bill but one that might provide the basis for a final agreement with the House. But first McConnell had to win a majority of Senate votes to begin the consideration of health care legislation, by adopting a “motion to proceed.” Opponents of both the House-passed bill, the legislation pending before the Senate, and the substitute—marginally less severe, that McConnell was planning to offer—feared, not without reason, that if the motion to proceed was successful the Senate would pass a bill undoing a significant portion of Obamacare and that one way or another a final bill would be some form of the most damaging bills each chamber had been able to pass.

Because of his party’s narrow majority in the Senate, McConnell could afford to lose the votes of only two Republicans on the motion to proceed, and if that succeeded, on a series of amendments that would be offered as substitutes for the House-passed bill. Vice President Mike Pence could break the resulting tie. By Monday July 17 two Republicans had already said they’d oppose the motion to proceed; and then in the course of that day two more said so (that kept either one of them from being blamed for casting the decisive vote), which appeared to put an end to the Republicans’ effort to replace Obamacare with something more to their liking. And then, two days later, came the awful news that McCain had an aggressive brain tumor.

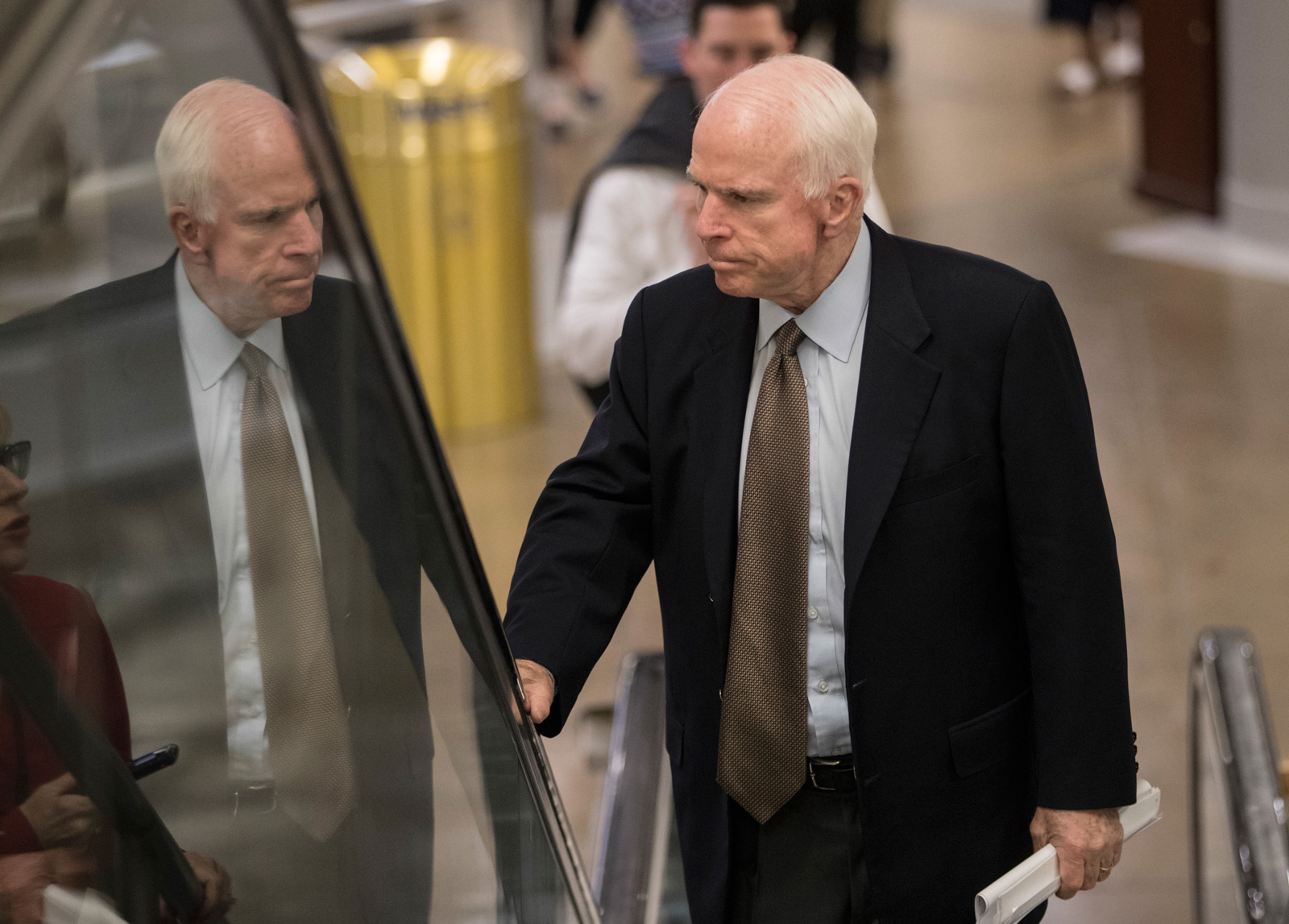

The Republican effort to undermine Obamacare looked moribund going into the following weekend. But it’s not a good idea to underestimate McConnell’s determination and resourcefulness. In fact, he was in a position to move around some funds in his pending proposal to satisfy the complaints of various Republicans whose votes to undo much of Obamacare weren’t assured. (Or who, for their own purposes, had indicated that their votes weren’t assured.) Leaders of grass-roots groups fighting to protect Obamacare began to get a sinking feeling over that weekend that McConnell might pull it off. And then came word that McCain, still recuperating from the surgery that disclosed his illness would fly back to Washington. McCain had voted against Obamacare more than once and it stood to reason that he wouldn’t be returning simply to cast a vote to save the program.

McCain received a hero’s welcome from all the senators and Senate staff members on the floor when he arrived on Tuesday afternoon, and the chamber was dead quiet as he delivered what was possibly his last address to the Senate. McCain is loved by many of his colleagues, including some Democrats, and respected by virtually everyone in the body—he’s been through unimaginable experiences—though along the way his crusty side has irritated more than a few of them. His speaking style is typically unoratorical and unadorned. But he tends to speak of things that people who know him understand come from a part of him that goes very deep and that has set McCain apart as one of the most striking political figures of this age.

This imperfect man has a deep reservoir of principle. Among the things that have offended him are distortions and degredations of the political process. Thus he went against his party in the early 2000s, after losing the presidential nomination to George W. Bush, and backed campaign finance reform—and prevailed. Now, standing by his Senate seat, he railed against the forces that have led our politics to a new low of hyper-partisanship—for which he blamed both parties—and he criticized the secretive methods by which the issue before them had been handled. He asked, “Why don’t we try the old way of legislating in the Senate?” On Tuesday, when McCain cast his vote for the motion to debate the Republican health care legislation to proceed, some of his fans were let down and the cynics who had never quite got past their doubts about him felt vindicated.

McConnell’s victory on the motion to proceed didn’t carry over to the various proposals for replacing or at least seriously undermining Obamacare. One by one alternative plans were voted down. Then it was learned that McConnell was working up a “skinny” repeal bill—a stripped-down package of cynicism that would repeal some parts of Obamacare but was designed to win fifty votes. (With Pence casting the 51st vote in its favor.) There was ample reason to fear that if the Senate passed the skinny proposal that House might agree to it and that would be the nation’s new health care law. Even if the House leaders took the more conventional route of conferring with the Senate to arrive at a compromise—it wouldn’t be easy but the basis was two bills to significantly roll back Obamacare.

There was also good reason to expect McConnell to prevail once more. The only Republicans expected to oppose this last attempt to radically change Obamacare were Susan Collins of Maine and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska. The Trump administration’s lack of finesse in trying to persuade holdouts made itself apparent when Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke phoned Murkowski and threatened to retaliate against the state of Alaska—the department’s policies on minerals and the development of energy resources has a large impact on the state—if she voted against replacing Obamacare. (Zinke made the mistake of taking on a committee chairman, and Murkowski, who heads the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, threatened retaliation by holding up the nomination of Zinke’s deputy. One can’t help but think that Zinke, a former congressman from Montana, knew better but was under pressure from the White House.

McConnell stalled action while he tried to obtain a sufficient number of votes. Pence made a rare excursion to the Senate floor to work on McCain. If McCain was holding out, Pence should have known better than to think that trying to persuade him would change McCain’s mind at this point. When McConnell at last let the vote proceed on the skinny repeal, McCain’s decision remained unknown to the public until after the first round of names were called. And then the old warrior entered the floor. McCain’s most dramatic vote was cast most undramatically. Not for him the Jimmy Stewart theatrics, the calling attention to himself. When his name was called he turned a thumb down—to some audible gasps in the chamber—and without a glance to his colleagues he quietly returned to his seat.

As usual with McCain there was a lot more subtlety to his act than has been imputed to him. Democratic leader Chuck Schumer told a reporter for The Guardian afterward that he and McCain had spoken “three or four times” a day for the past few days, and one subject was the secrecy with which the Senate had proceeded. (Schumer knew who he was talking to.) A very few other Republicans were also troubled by what the Senate was about to do—this included McCain’s closest Senate friend, Lindsey Graham. But by casting the deciding vote McCain offered them protection from the fury of the base had they themselves voted against changing Obamacare. And there was another thing: candidate Trump had delivered a particularly low blow to McCain by saying that he had greater respect for military personnel who weren’t captured. He charged McCain with not helping veterans. McCain doesn’t forget such things. McCain also had long had an at best tense relationship with McConnell — the leading Senate opponent of campaign finance reform. Besides, the rather free-spirited McCain and the grim, win-with-whatever-works McConnell, both of them big figures in the Senate, were rarely in tune.

After the vote, McConnell, in a sour speech, accused the Democrats of “celebrating” and rehearsed the familiar litany of charges against Obamacare. But having discharged that duty McConnell, a practical man undoubtedly eager to put the long-fought issue behind, said “It’s time to move on.” The biggest loser of the fight was of course Donald Trump, who now has little besides his executive orders (and of course his one Supreme Court appointment) to show for his record so far. And so Congress prepared to recess for August with many of its members as well as political observers concerned that Trump might create chaos by trying to stamp out the Russia investigation, and nervously wondering how the tempestuous president’s fractured and faltering administration, even with a new chief of staff, would perform in an international crisis.