In the summer of 2015, I went to Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library with a difficult question. I had been researching the relationship between city life and conceptions of “the lyric” and was working on a chapter about the poet George Oppen’s Discrete Series (1934), a book that remains enigmatic even eighty years after its initial publication. A group of thirty-one short, mostly untitled poems that evoke the experience of modernity but prefer subtlety and syntactic contortion to direct emotional expression, Discrete Series received astonishing support upon release. Ezra Pound contributed a preface that concluded: “I salute a serious craftsman, a sensibility which is not every man’s sensibility and which has not been got out of any other man’s books.” William Carlos Williams wrote a glowing review of it for Poetry magazine, praising Oppen as “a ‘stinking’ intellectual” whose verse rests “on a craftsmanlike economy of means,” and went on to predict that Oppen’s work would push readers to remember that “poems are constructions.”

But their shared awe of Oppen’s craftsmanship was not broadly predictive. Oppen would not publish another book until the 1960s, and would not win the Pulitzer Prize until 1969. The poems in Discrete Series appear rather seamless and gnomic, leaving readers with few clues as to how to read them. For the most part, the poem sequence has been seen as a kind of momentary eruption rather than a slow accumulation of effort—a brief poetic apprenticeship before Oppen turned to political activism and chose not to write any poetry for almost twenty-five years.

As Oppen’s political convictions whisked him around the United States, then to France and Germany in the Second World War (where he was wounded), back to New York, and then to California, he came to the attention of the FBI. The first entry in his heavily-redacted file is dated 1941: “The subject was Kings County election campaign manager for Communist Party in 1936 elections. Voted Communist Party ticket in 1936….Subject not found and therefore not being considered for custodial detention.” Oppen couldn’t be found because he was already in Detroit, working as a pattern-maker in the Machinists Union, and then in Louisiana, where he received basic training.

FBI surveillance increased after he returned from the war until a dramatic confrontation with two agents in early 1950, at their home in Redondo Beach, led Oppen and his wife Mary to flee to Mexico. Whatever correspondence or manuscripts George had maintained from the 1930s were lost in the urgency of their departure, and as a result, there has been little in the way of surviving material to provide us with insight into what he was thinking and reading as he wrote Discrete Series. I visited the Beinecke with the hope that Pound and the poet Louis Zukofsky, both of whom were in correspondence with Oppen, would have discussed his early writings in their extensive exchange.

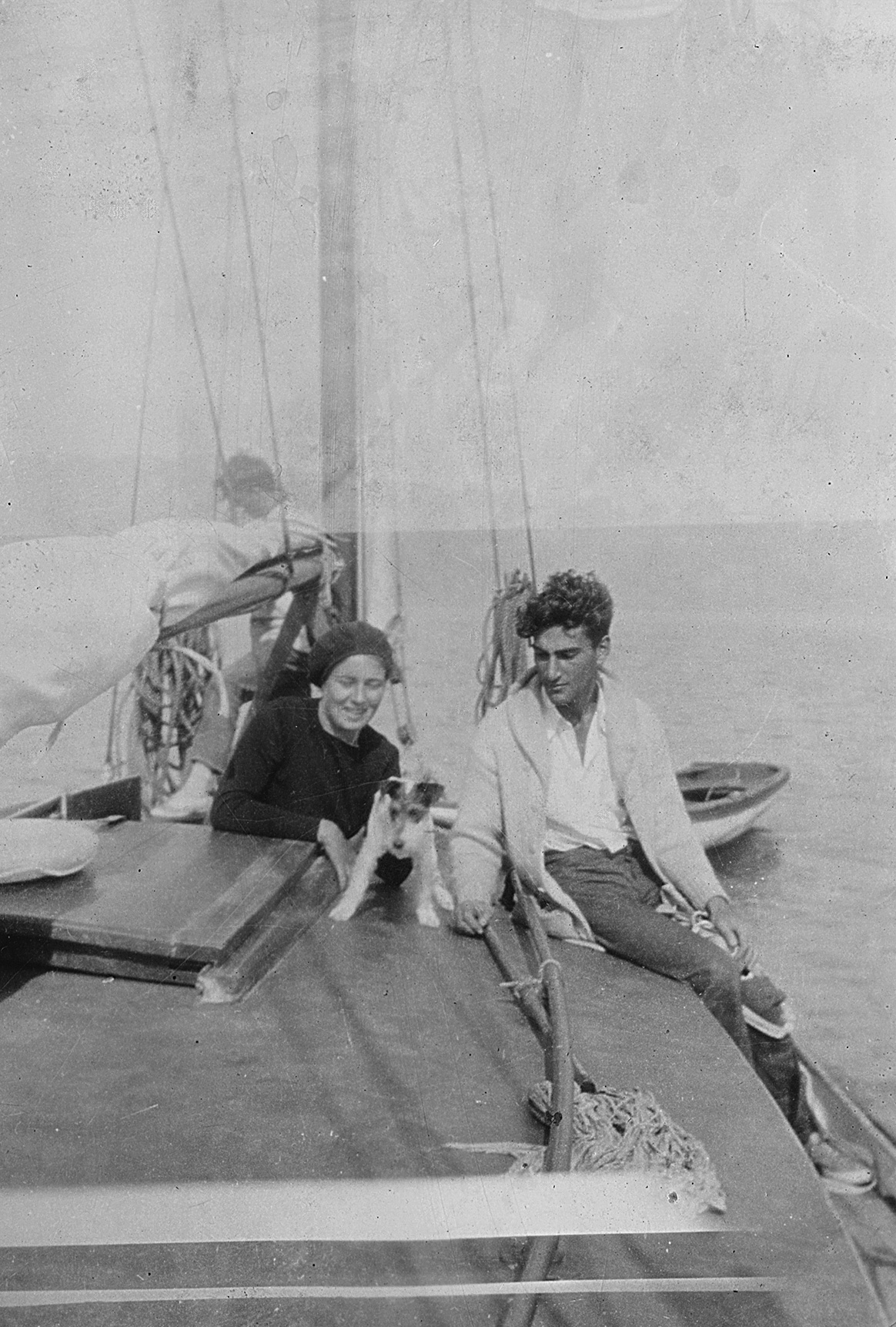

What I found was something far more exciting than I could have imagined: an early Oppen manuscript. “May have 32pp of poems by George Oppen for you,” Zukofsky had written Pound on March 6, 1930. Scholars have long assumed that the “32pp” to which Zukofsky referred comprised a draft of Discrete Series that had been lost, like the sheaf he sent to Charles Reznikoff in late 1933, now held in the Archive for New Poetry at the University of California, San Diego. But the assemblage Zukofsky sent Pound six weeks after he wrote that letter—an unbound sheaf of typewritten poems varying dramatically in voice and style, one per page, with the heading “21 Poems by George Oppen” handwritten in pencil on the first page—shows a larger, more dynamic body of work. Only one poem in the typescript can be found in Discrete Series—the final poem, “The mast”—but Oppen published (and tried to publish) these poems for several years after sending them to Pound, suggesting that elements of both collections coexisted for a period of time. In fact, the second, fifth, sixteenth, and twenty-first poems were originally published together as four sections of a different “Discrete Series.” These poems can be seen as precursors to Discrete Series in theme and approach. Oppen’s love for his young bride, his love of sailing, his skepticism about the impact of modern finance and technology on social life, are evident in both sets. Some of the earlier poems seem like the Imagistic experiments that readers might have expected from an acolyte of Pound, tempered with a Williams-esque fascination with everydayness (“One remembers the smell of warm paint”).

But there are also many differences between the two collections. Although Discrete Series includes several poems about seafaring, rural highways, and the metropolis, it rarely seeks to bridge the conceptual distance between these disparate living spaces. (Williams noted “the colors, images, moods [that] are not suburban.”) The work in 21 Poems, however, often seeks a resolution outside of the urban setting. As a whole, this earlier collection has a much greater breadth of tone and mood, and certain poems function in rhetorically theatrical ways that Discrete Series rarely allows. Some even read like burlesques of poetic clichés (“The moon rose like a rising moon”) or as critiques of cosmopolitan habits (“Your coat slips smoothly from your shoulders to the waiter: / How, in the face of this, shall we remember”). 21 Poems also includes more individuals who are identifiable beyond a spare “he” or “she” pronoun, some of whom are addressed with remarkable intimacy (“Here put your head, that desires nothing except familiarly”). These poems eagerly display a skeptical intelligence and turn to irony to comment on the scenes they describe. The first of the earlier sequence, which dramatizes the experience of giving birth, is by far the longest of Oppen’s early career. It is nearer a poem like “Parturition” by Mina Loy, who the Oppens would eventually meet in New York, than anything about fatherhood written by other male modernists. The poem shifts constantly between narration, exclamation, and query—the total effect more impressionistic than “objective.”

Advertisement

There has been a recent surge in Oppen scholarship, supported by published volumes of interviews (Speaking with George Oppen, edited by Richard Swigg), prose (Selected Prose, Daybooks, and Papers, edited by Stephen Cope), and reminiscences from the Oppens’ many friends (The Oppens Remembered, edited by DuPlessis). But this is the first publication of new material that precedes Oppen’s storied twenty-five years of silence between the publication of Discrete Series and his next book, The Materials, in 1962. 21 Poems nearly doubles the size of Oppen’s early and influential corpus, and happily, the poems themselves are fascinating. The simple act of sending them to Pound indicates Oppen’s ambition, as well as Zukofsky’s confidence in his younger friend’s work. When I first shared my find with one of my professors, he grabbed my shoulders and said, “Don’t get used to this feeling, David, it may never happen again.”

III

This a vacant lot;

Impenetrable ground

Of embedded stones,

Bottle-glass.

My shoes grow

Dusty, not of soil.

No nor elsewhere. Simply

This, and my dissatisfaction.

Between eyes and shoes, a plane,

A spaced companionship, opposing

This dust, and some immovable watchfulness.

IX

The revolving door swings load after load into the lobby;

There is a sound of secrets,

A scattering of feet, a crossing, recrossing.

But now, with the sudden weight of prophecy,

Incredibly caught stillness,

The carpet level to the door. From outside,

Short clatter of a street-car— a policeman’s whistle

Barely heard.

Now first visible,

Steadily back and forth,

Past and past the newsboy (straining, silent),

Unvaryingly waiting, overcoated,

Walks the doorman. As in a dark house

A wicker chair cracks suddenly in the attic.

XV

One remembers the smell of warm paint:

Bread and butter left on the wood step of the porch.

Round clouds above;

Between,

Everything very brightly

Not there.

XX

So he stood on the island— over the sea

Until creation was a cone with polished sides.

Starring— a man before a bill-board.

Looked to where the shallow-edged sea drew at a pebble, white

Whole; pebble even nowhere. Emerged

Clearly into solitude.

He

Possibly saw creation

Barely curve the water,

Circumscribe his unshaping feet.

We, you and I, will go all over the world.

Will feel minutely, adequately heavy as a curving kite-string from a

hill.

Fields, the porches of houses, the cornered ways of cities—

We will walk everywhere as at each step our toes spread on grass.

Heads above them, interval planed by chins.

On the island (if he smiled ever smiled)

Sank his feet slightly into sand. Filling nothing.

21 Poems by George Oppen, edited by David B. Hobbs, is published by New Directions.