In Persia and the Persian Question (1892), Lord George Curzon, later the viceroy of India, remarked, “The Oriental intellect seems to derive a peculiar gratification from the display of duplicates.” He went on to affirm that, “Whereas the Persian taste, if restricted to its native art or to the employment of native styles, seldom errs, the moment it is turned adrift into a new world, all sense of perspective, proportion, or beauty, all aesthetic perception, in fact, appears to vanish.” Curzon’s complaint would be echoed by Western art historians for the next hundred years. For many European visitors of the nineteenth century, Persian art was a tasteless mishmash: poor imitations of European work and bastardized objects that had lost the dignity of the native “tradition.”

The exhibition “Technologies of the Image,” now at the Harvard Art Museums, suggests how wrong they were. The show is fascinated by precisely the thing that repelled Curzon about art of the Qajar period (1779–1925)—its hybrid aesthetic, a combination of “native styles” with European sources and technology. The objects in the exhibition aren’t displayed for their originality, but rather for their creative repurposing of existing—often foreign—images and subjects. The curators are especially interested in what they call “remediation,” that is, images made in one medium subsequently emulated in another: a painting that incorporates a photographic model, for example, or a lithograph based on a sculpture. If the objects in the show don’t immediately take one’s breath away—it sometimes seems they were selected expressly not to do so—the longer one studies them, the more absorbing they become.

Throughout the long nineteenth century, Iranian artists embraced new technologies from Europe—the lithograph and photograph chief among them—and adapted them to their own purposes. Although images from Europe had long circulated in the Persian market, these two technologies produced a flood of cheap reproductions arriving in newspapers, postcards, and prints that provided Iranian artists with a wealth of new subjects.

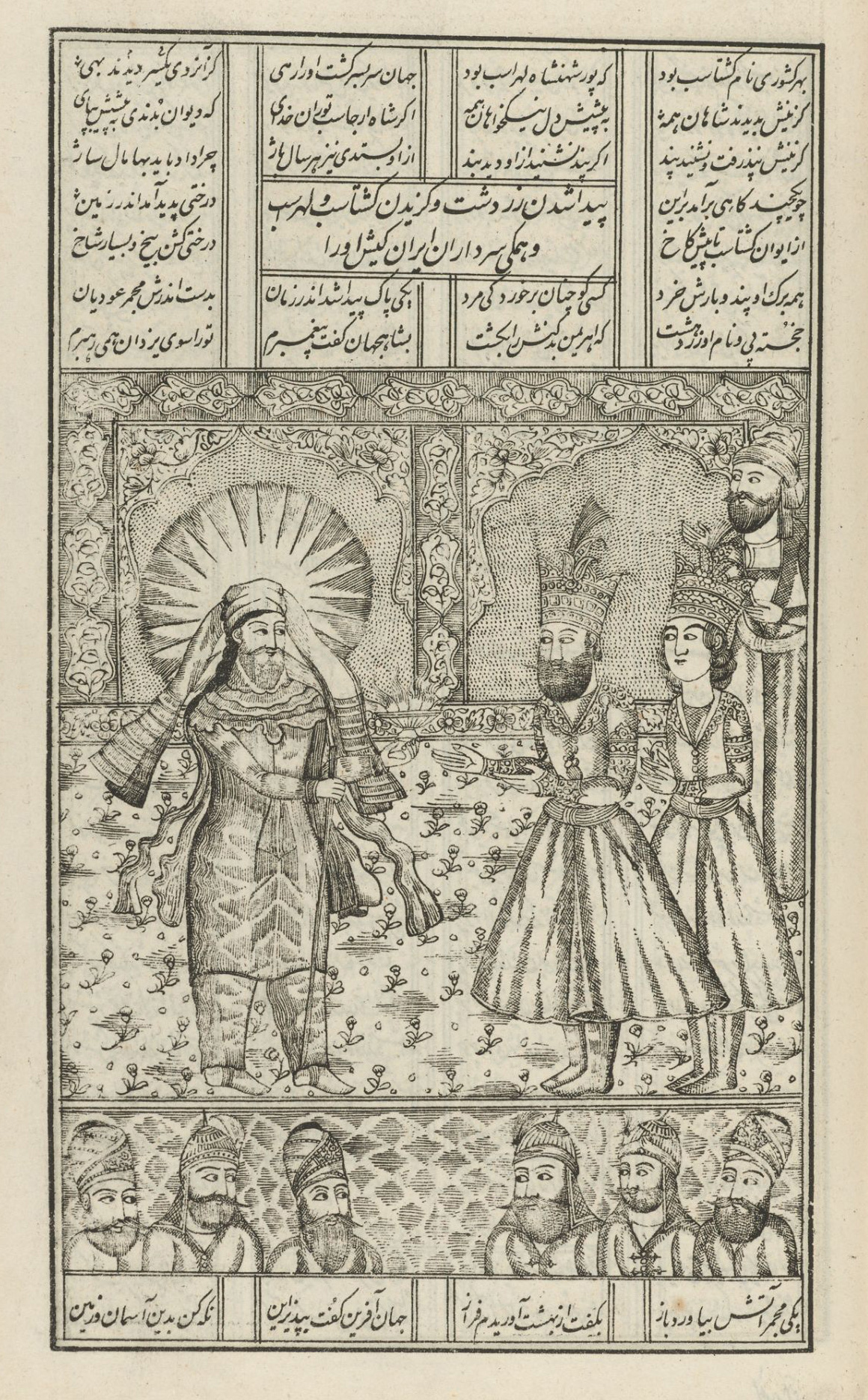

In Tehran, the first lithographic edition of the Shāhnameh (Book of Kings), the Persian national epic written by the poet Firdawsi in the late tenth and early eleventh centuries, was printed between 1848 and 1850. One of the volume’s illustrations shows the prophet Zoroaster offering a flaming coal, held with the tips of his fingers, to king Goshtasb, a legendary ruler who helped to spread the faith. This illustration was modeled on a lithographic print of the Shāhnameh made two years earlier in Bombay (home to a large Parsi Zoroastrian community), which was in turn modeled on a rendering of fourth-century Sassanid rock reliefs by the British artist and traveler Robert Ker Porter. In a book of drawings published in London in 1821, Porter suggests that the haloed figure in one of them “may be meant for the glorified Zoroaster.”

The Shāhnameh lithograph, now on display at Harvard, is not a dazzling piece to look at. But once one knows something of its tangled history—detailed in Farshid Emami’s expert catalog essay—it does become interesting to think about: the static, two-dimensional print acquires third and fourth dimensions of formal and cultural complexity. As Emami notes, the Tehran Shāhnameh marks an important moment in the history of the book in Iran: with the advent of lithographic print—not a mass-market edition, but also not a courtly manuscript—a broader public could read the national epic in the privacy of their homes.

“Technologies of the Image” is full of objects like the lithograph: images inhabited by a history that spans several media, artistic traditions, and types of audience. This eclecticism has long been recognized as a hallmark of art from the Qajar period. The Qajars, a Turkmen tribe from northern Iran who established their capital in Tehran, were not effective rulers. Although they came to power through military success, defeating rival dynasties in a series of brutal wars, they soon lost all territory in the Caucasus Mountains to Russia. They also gradually amassed a ruinous debt to Britain, which used its leverage to extract concessions and gradually open up Persian markets. By comparison with the ambitious reform measures carried out during the same period in Cairo and Istanbul—state centralization, urban construction, military development—the Tehran regime’s attempts at modernization were halfhearted at best.

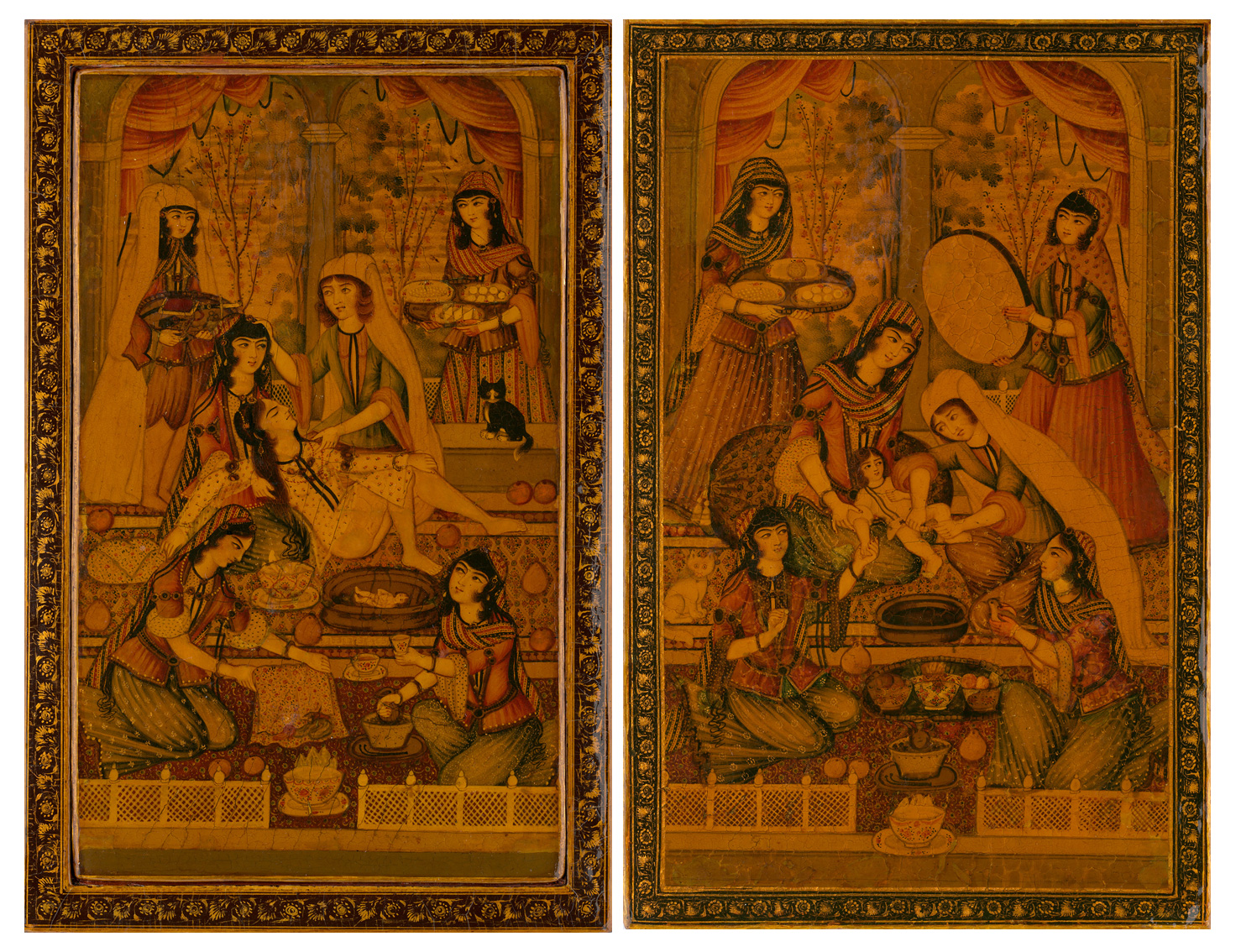

Lacquer snuff boxes, pen cases, and mirror covers were especially prized objects of Qajar artistry. Robert Murdoch Smith, a British resident of Tehran who acquired antiquities for the Victoria and Albert Museum, wrote, “The best paintings in Persia are those on a miniature scale on papier-mâché writing cases, (Kalemdans), and book-cases, and small wooden boxes.” The Persian technique, which employed a papier-mâché substrate rather than the tree sap used in Chinese and Japanese lacquerware, was developed in the fifteenth century primarily for decoration of deluxe book covers. Many scenes shown on Qajar lacquers were taken from the tradition of illustrated poetry books, but others were borrowed from popular European prints of reclining nudes and mondain lovers.

Advertisement

Still others borrow from Christian iconography. One of the most striking lacquers at Harvard is a mirror case showing, on one side, a woman giving birth and, on the other, a circumcision ritual. In the latter scene, the poses of mother and son are clearly derived from representations of the Virgin and Child (the kneeling attendant, about to release a bird to distract the boy from the coup de grace, is also derived from Christian sources). But the Qajar scene, essentially domestic and decorative, has been divorced from its religious origin.

A more striking case of “remediation” is a portrait of the Qajar ruler, Nasir al-Din Shah (who reigned from 1848 to 1896). In the painting, which dates from the late 1850s, the Shah is surrounded by objects that give the painter little opportunities for showing off: sprays of flowers, a painted battle scene, a glass globe, patterned furnishings, and decorative trim on the wainscoting and window. The pictorial space is conventionally flat and without unified perspective. The Shah, however, is modeled on a photographic original, as suggested by the easy pose of the body, the shading of the face below the moustache, and his natural expression. He sits atop a stack of tightly stuffed cushions, which strategically cover the convergence of wall lines, like a real body set afloat in low-gravity conditions.

The portrait of the Shah combines two codes, photographic realism and painterly convention. It’s just the sort of object, apparently lacking in perspective and proportion, that exasperated Curzon and led him to lament the vulgarization of “Persian taste.” But perhaps such images do not suggest decline so much as the strength of an artistic practice able to assimilate foreign matter. It was European visitors, paradoxically, who were most anxious about the loss of a putatively pure native tradition. As David J. Roxburgh notes, in his catalog essay on painting and photography in nineteenth-century Iran, Persian painters were very rarely trained in drawing from life, and so the insertion of a photographic subject into a stylized interior required little change in practice or pedagogy.

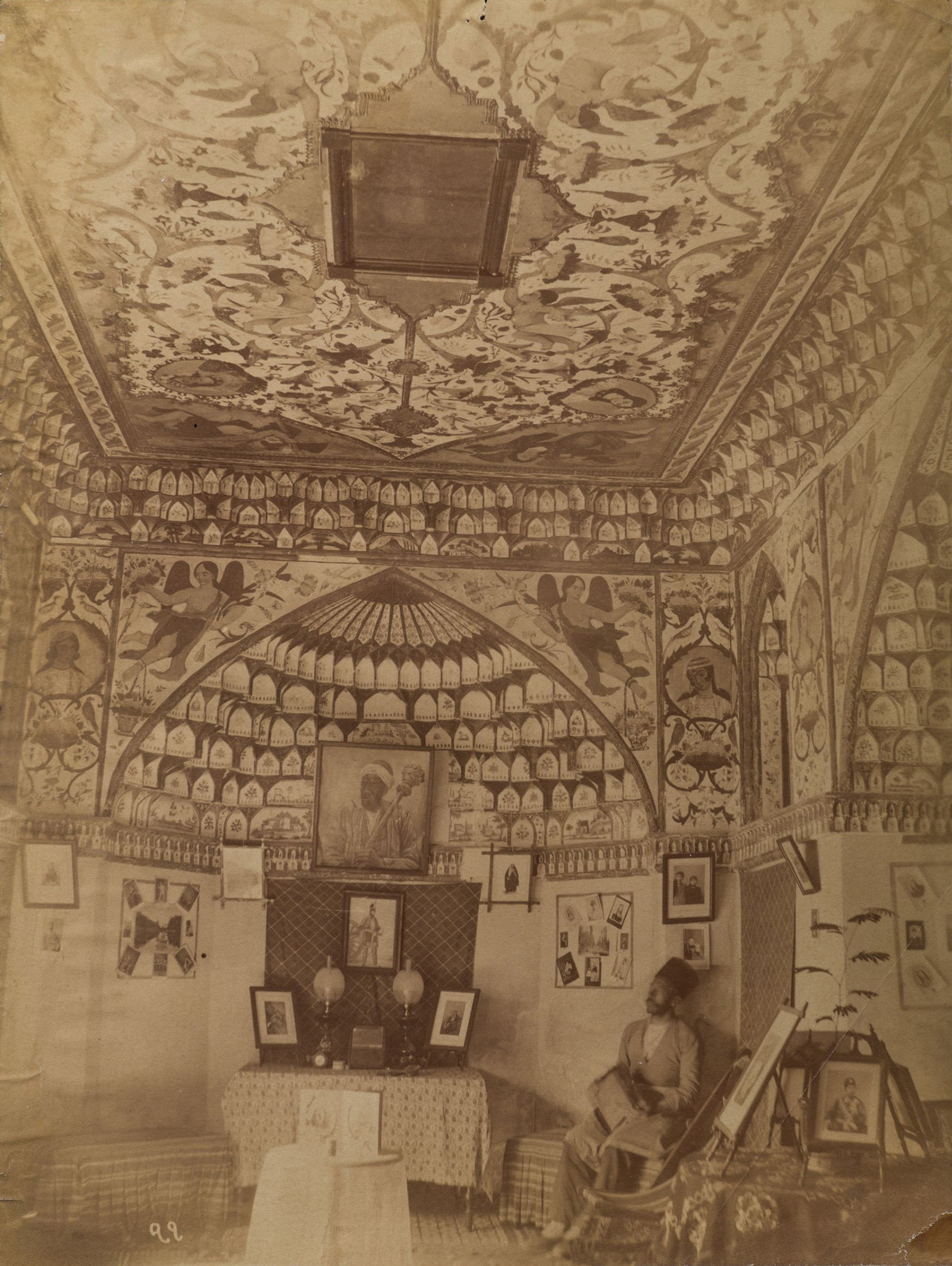

Seen in this light, the influx of images from abroad and the wave of images made by Persian artists in response do not suggest a native tradition under siege so much as a studied delight in the new abundance of things to see and to make. That is certainly the impression one gets from a peek inside the display room of Antoin Sevruguin, son of a Russian diplomat and Georgian mother, who established a studio in Tehran around 1870 and became the best-known photographer of Qajarite Iran. Mira Xenia Schwerda’s erudite essay on Iranian photography tells how Sevruguin’s early training as a painter in Tbilisi included the study of old masters as well as Persian miniatures. This mixed heritage of painting and photography, East and West, is visible in his display room, a jewel box that suggests pleasure in profusion rather than artistic anxiety.

The spirit and techniques of miniaturism are much on display in the Harvard exhibit. Many pieces have magnifying glasses hanging next to them and one can spend hours happily scrutinizing their small-scale virtuosities. The size of the objects neatly matches the curators’ argument that Persian artists were able to incorporate foreign material into longstanding traditions. The emphasis on smallness might skew the evidence in their direction. According to the art historian Oleg Grabar, it’s the monumentality of some Qajar art—such as the large royal portraits on view in a Brooklyn show some twenty years ago—that represents a “total rupture with the past.” But this, too, is debatable. In the seventeenth-century palaces of Ali Qapu and Chihil Sutun in Isfahan, there are wall frescos as large as any paintings from the Qajar period. “Technologies of the Image” persuasively suggests that originality isn’t the best lens for looking at the art of nineteenth-century Iran—nor, perhaps, for many other periods and places where European technologies and non-European traditions encountered one another with fascinating results.

Advertisement

“Technologies of the Image: Art in 19th-Century Iran” is at the Harvard Art Museums through January 7, 2018.