Lawyer, art lover, and Philadelphian John G. Johnson is among the least known of the buccaneering American art collectors who flourished during the Gilded Age. Unheralded outside of his native city, Johnson (1841–1917) was the nation’s leading corporation lawyer, his practice prospering in concert with the ascent of the industrial titans. His clients were the richest companies in America, including Standard Oil, J.P. Morgan and Co., United States Steel, the Pennsylvania Railroad, the American Tobacco Company, and the American Sugar Refining Company, and he enjoyed unparalleled success defending their monopolistic practices against prosecution under the Sherman Antitrust Act. He argued 168 cases in the Supreme Court, and reportedly declined to be nominated for a seat there because he couldn’t afford the pay cut. Johnson was pulling in $100,000 a year (roughly $2.7 million in today’s money, but a small sum compared to the income of his clients and collecting rivals Morgan, Henry Clay Frick, and Henry O. Havemeyer).

In the early 1880s Johnson began buying French, Italian, Spanish, Dutch, German, and Flemish paintings. In 1892, when he published a small book titled Sight-seeing in Berlin and Holland Among Pictures, he owned 281. At his death Johnson had amassed more than 1,300 works of art, which he left to the City of Philadelphia. When they were later transferred to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Johnson became that institution’s greatest benefactor.

Johnson’s acquisitiveness and acumen are commemorated on the 100th anniversary of his bequest in “Old Masters Now: Celebrating the Johnson Collection,” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. As the title of the exhibition implies, Johnson chiefly collected medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque painting, but the glorious eye-opener of the show turns out to be his discerning response to the art of his own time. Schooled first in conventional realist painting, he became a believer in the man who revolutionized it. Johnson was partial to landscapes, seascapes, and portraits by Gustave Courbet, and the lambent Marine is on view. In this seascape painted in Trouville in 1866, Courbet records the phenomenon of a waterspout, a column of water and spray churning in the sky. The painting is radically direct. Courbet faces the sea, orchestrating our impression of being in the scene by contriving a low horizon and a great space for the forceful play of clouds, atmosphere, and sky. The exquisitely calibrated variations of light and weather over the English Channel reminds us of Turner and presages Impressionism, but the materiality of thick paint and his liberal use of a palette knife to apply it are pure Courbet.

Another transfixing canvas is Basket of Flowers and Fruit (1848–1849), a passionate late still-life by Eugène Delacroix trembling with bravura contrasts. The long, horizontal arrangement of richly colored flowers and fruit, set against the verticals of a delicate background of roses, hollyhocks, and greenery cut by a wedge of bright sky, surges voluptuously out of the canvas with a command of push-and-pull that Hans Hofmann would have appreciated.

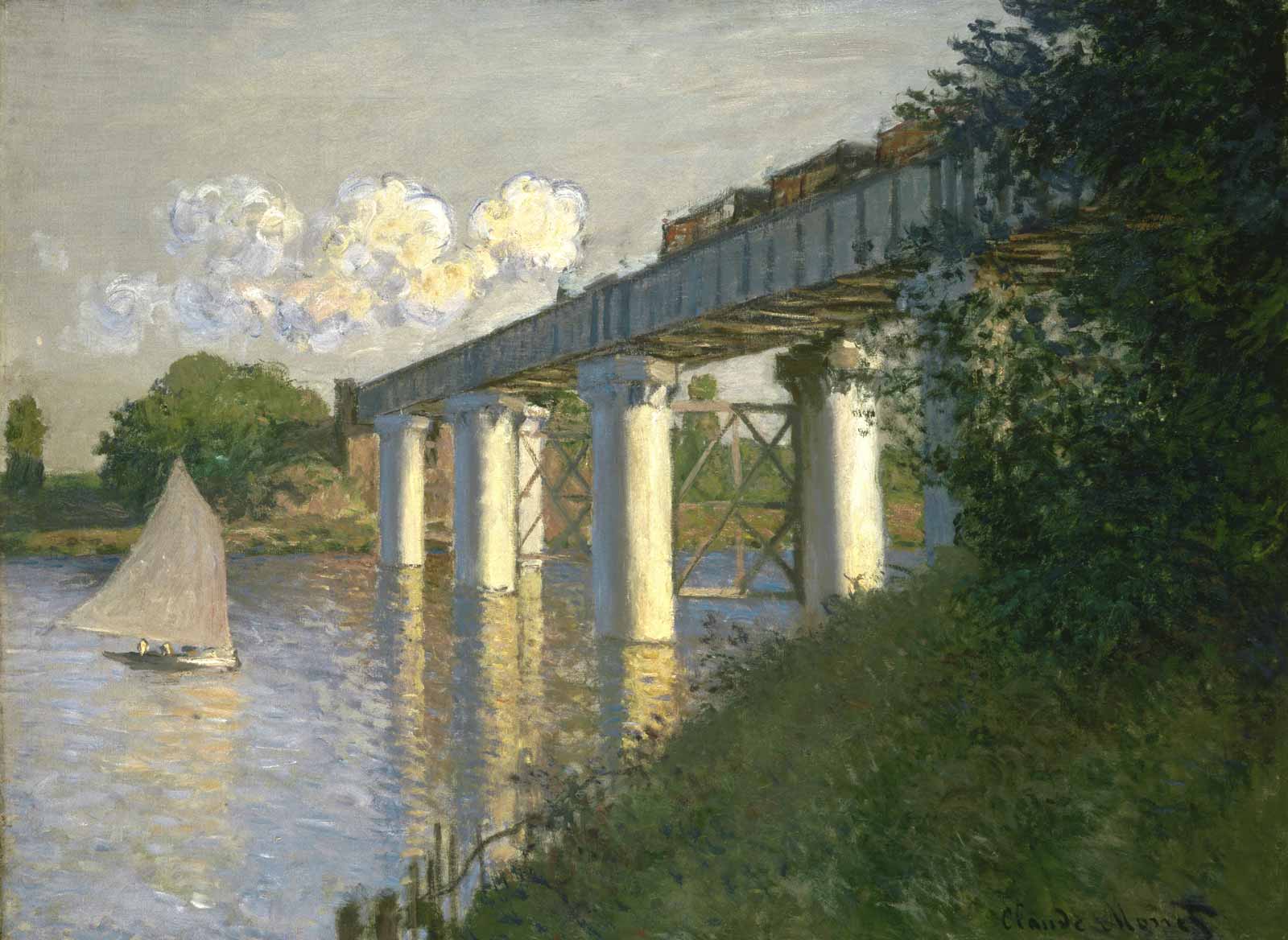

Johnson bought especially adventurously in 1887–1888, adding Édouard Manet’s majestic The Battle of the U.S.S. “Kearsarge” and the C.S.S. “Alabama” (1864), for $1,500, Railroad Bridge, Argenteuil by Claude Monet (1874), and The Moorish Chief (1878), a superb Orientalist portrait by Eduard Charlemont, to his possessions. All three paintings by James McNeill Whistler in Philadelphia’s collection were originally acquired by Johnson, as was its first canvas by Winslow Homer.

In a somewhat confusing layout, the show is divided into galleries dealing with Johnson’s life and times in Philadelphia, the formation of his collection, examples of the variety of artists, schools, and movements he admired, and works of art that proved to be different in appearance or authorship than what Johnson thought. The results are a jumbled but rewarding portrait of a remarkable figure. The son of a blacksmith, John Graver Johnson was a scrivener in a local law office at sixteen. He went on to enroll in the University of Pennsylvania Law School, and was admitted to the Philadelphia bar in early 1863. By the late 1860s, Johnson headed a busy practice, working for real estate and insurance agencies, and then moved into trial law. In 1875, he wed Ida Powel Morrell (1840–1908), a widow with three children whom he met when she consulted Johnson about her late husband’s estate. The pictures she inherited and brought to the marriage were the first known works of art in the Johnson collection.

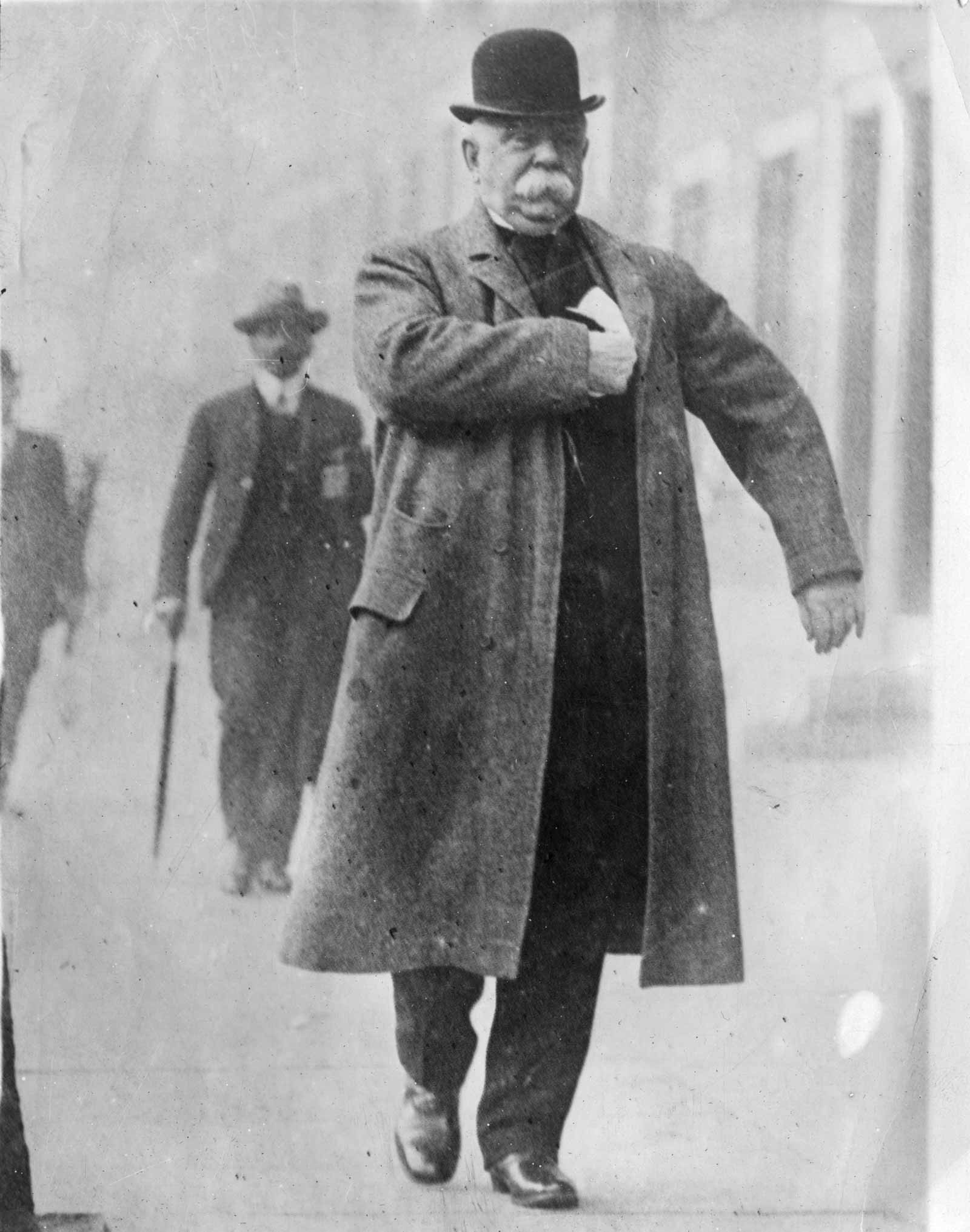

Six feet tall, Johnson was a big, beefy man with a walrus moustache and a fondness for oysters, regularly polishing off a dozen or so for lunch. His appetite for art was just as vast. The beginning of the exhibition adroitly documents how legal services fed into felicitous acquisitions. One of Johnson’s clients was Alexander Cassatt, an executive of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and the brother of Mary Cassatt. This connection prompted Johnson to buy The Flirtation: A Balcony in Seville (1872), an early painting by the artist, in the mid-1870s. Another Philadelphian needing a lawyer was Thomas Eakins, who consulted Johnson in 1887 for unknown reasons. Johnson accepted the watercolor Drawing the Seine (1882) as payment, writing to Eakins, “I am very much your debtor for your delightful little watercolor.… It is admirably drawn and composed, full of movement, air and sunlight and charming in color.” (Many years later, Johnson received a watercolor from John Singer Sargent for helping him with his mother’s will.)

Johnson probably avoided more fakes than other self-taught collectors, although he did fall victim to optimistic attributions. He thought he was giving eleven paintings by Hieronymus Bosch to Philadelphia, but the section of the exhibition devoted to conservation and curatorial discoveries tells us that, of the original group, only one is still deemed a genuine Bosch. As his reputation as a collector grew, he asked art experts for advice. Bernard Berenson found him a Titian portrait and a seductive genre scene by the sixteenth-century Italian painter Callisto Piazza, but after examining the collection, he waggishly warned Johnson that “there are always a certain number of pictures that won’t go into the witness-box to be cross-examined.” By then Johnson was distinguished enough to merit a visit by Henry James when he toured the United States in 1904–1905, and he makes an anonymous appearance in The American Scene. James describes “a friendly house” in Philadelphia “that was given over, from top to toe, to a dazzling collection of pictures…. remarkably rich the store of acquisition, in the light of which the whole energy of the keen collector showed: the knowledge, the acuteness, the audacity, the incessant watch for opportunity.”

James perceived that the Johnson collection was much like its creator—a little baggy around the edges, but shot through with intelligence, judgment, self-reliance, and risk-taking. Perhaps Johnson’s overriding principle was eclecticism because he had long planned that his collection would serve the public. The Metropolitan Museum of Art was canny enough to make Johnson a trustee in 1910. Three years later, Bryson Burroughs, the Met’s curator of paintings, nearly lost his job in trying to purchase the museum’s first Cézanne from the landmark Armory Show of 1913. Johnson agreed with Burroughs, voting in favor of acquisition, and his reply sheds light on his own vision of what a public collection should be. Although the painting did not appeal to him, he acknowledged “that this is a mere matter of individual taste…. I think it well, also, for any Museum to have represented on its walls, examples, as far as possible, of everyone who stands for something in art. Cézanne does thus stand.”

Johnson never stopped buying: he made a deal for two paintings the day before he died. The collection overwhelmed nearly every square foot of usable space, and one gallery wall in “Old Masters Now” approximates a typical installation in the Johnson household, with pictures piled salon-style from floor to ceiling. However, the museum’s version is still too tidy to emulate the disorder in which Johnson really lived, as several photographs of progressively denser interiors reveal. The artist George Biddle, who saw the collection in about 1913, remembered, “He had eleven hundred masterpieces in a firetrap. … I found two Chardins in his boot closet, many examples of the Barbizon School in his bathroom; and Sargents, Manets, and French impressionists in corridors of the servants’ stairway.”

Johnson’s will stipulated that his collection be permanently displayed in his house on South Broad Street “for the benefit of the public.” If those terms were rejected, the entire hoard was to go to the Metropolitan Museum. But other Philadelphia lawyers prevailed in court, the collection was secured for the city, and pieces from it started trickling into the museum in 1930. What was intended for Philadelphia stayed in Philadelphia.

“Old Masters Now: Celebrating the Johnson Collection” is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through February 19, 2018.

Advertisement