Two hundred and twenty years ago, the English discovered Nature, and it was not by accident that this happened in an age of industrialization and revolution. Coleridge and Wordsworth wrote the Lyrical Ballads in rural Dorset and amid the even more remote Cumberland lakes and fells, while their contemporary John Constable painted idyllic rustic landscapes in Suffolk, and the stormy sea shore of Sussex. Meantime, coalmines and cotton mills were sprouting up across much of what another contemporary called England’s green and pleasant land, while across the Channel the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars devastated and transformed Europe.

Nor was it an accident that a number of English neo-Romantic artists flourished in the first half of the last century, also conditioned by, and reacting against, their circumstances. A serendipitous recent group of exhibitions, mostly in Sussex, makes the point. Despite some personal connections, these artists didn’t form a school or a movement, but their lives and work were shaped above all by the experience of war. All of them lived through the two great wars between 1914 and 1945, more terrible than anything Europe had known in Constable’s time; most of them served in uniform; and two lost their lives in World War II. What’s also striking, and significant, is the appeal some of these artists exert today, in an age that has no proper memory of war, and that yearns for what may partly be an imaginary past.

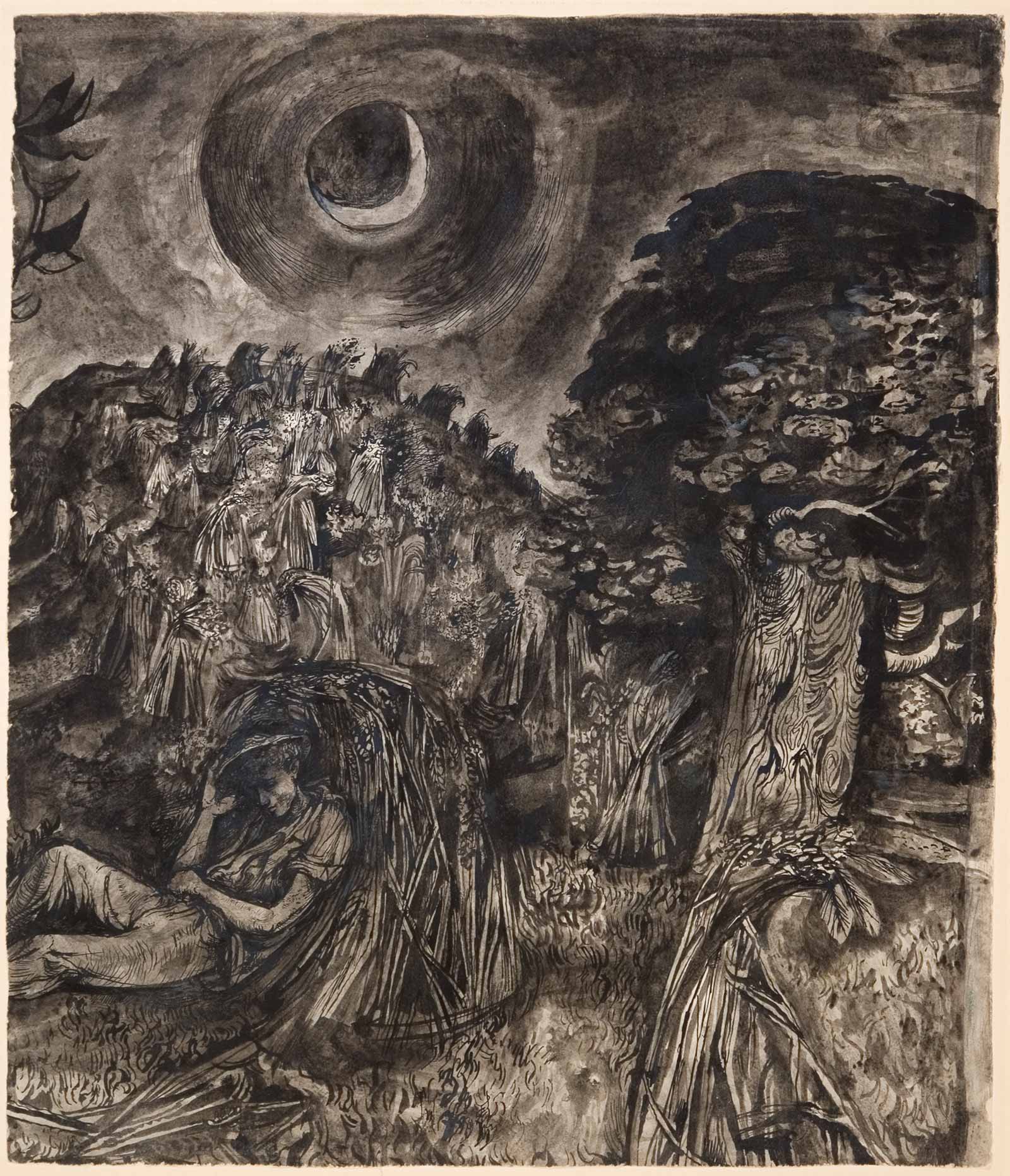

An earlier generation of artists had been caught up in World War I, notably David Jones (1895–1974) and Paul Nash (1889–1946). Two years ago, the admirable Pallant House Gallery in Chichester—now one of the best art galleries in England, which has staged a series of fine exhibitions around this larger theme—presented “David Jones: Vision and Memory,” and a year ago the Tate Britain showed “Paul Nash.” As both poet and painter, Jones had the most illustrious of admirers: W.H. Auden thought “The Anathemata” was “very probably the finest long poem written in English” in the twentieth century, and in the 1930s Kenneth Clark called Jones “the most gifted of all the young British painters.” But by some quirk of fashion, his work hasn’t gained wider recognition.

The Tate show illuminated how profoundly affected he was by his service on the Western Front. Although Nash would become a committed modernist, an associate of Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, it was his fate to be remembered as a war painter. The Menin Road, begun in 1918 and completed in 1919, is one of the most indelible images of trench warfare, with its desolate, crepuscular landscape of shattered trees and shell-holes. Twenty-two years later, Nash painted The Battle of Britain, which became just as emblematic of the next war as The Menin Road was of World War I: the fighter planes’ vapor trails criss-crossing amid cumulus clouds above the Channel as fleets of Luftwaffe bombers arrive.

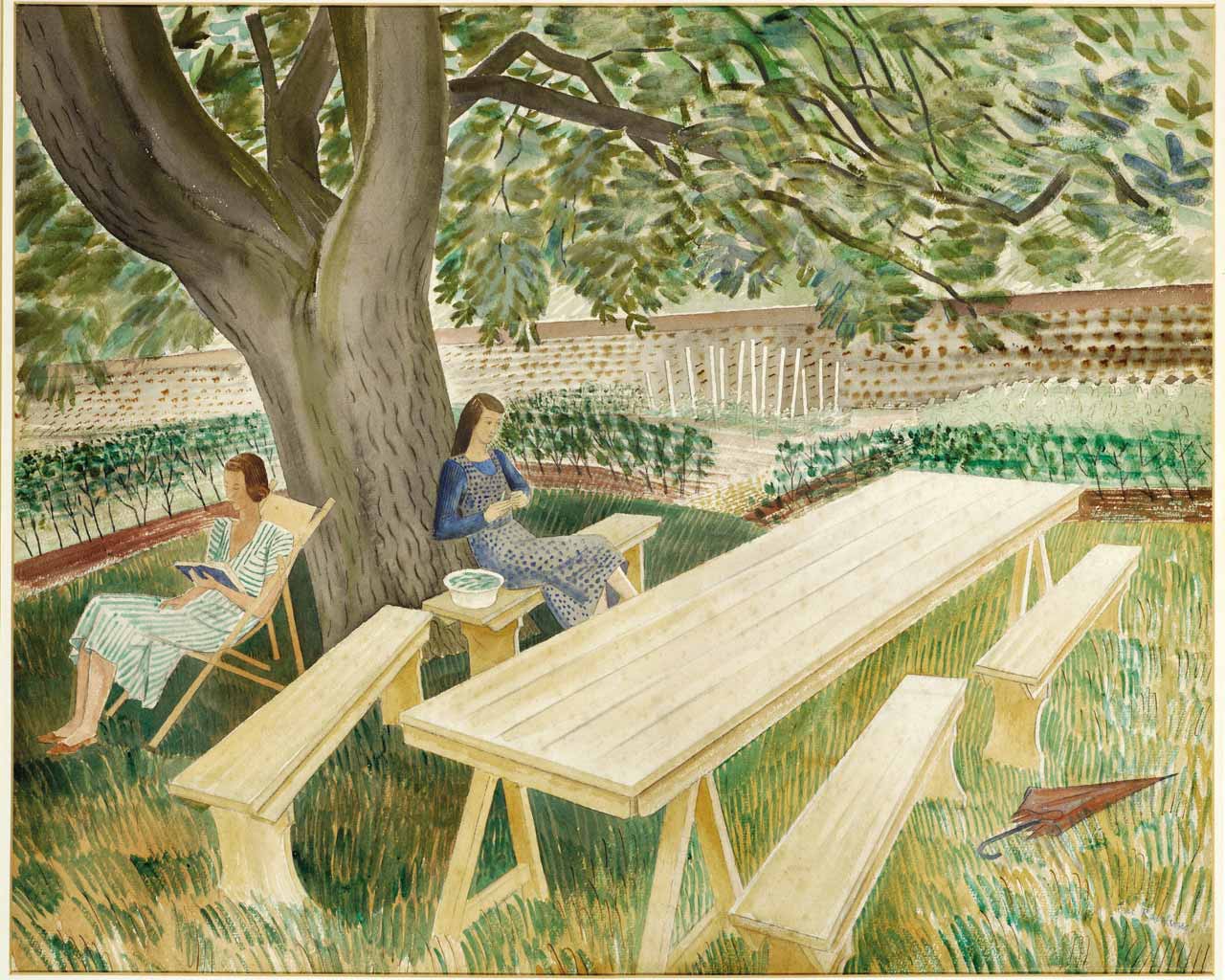

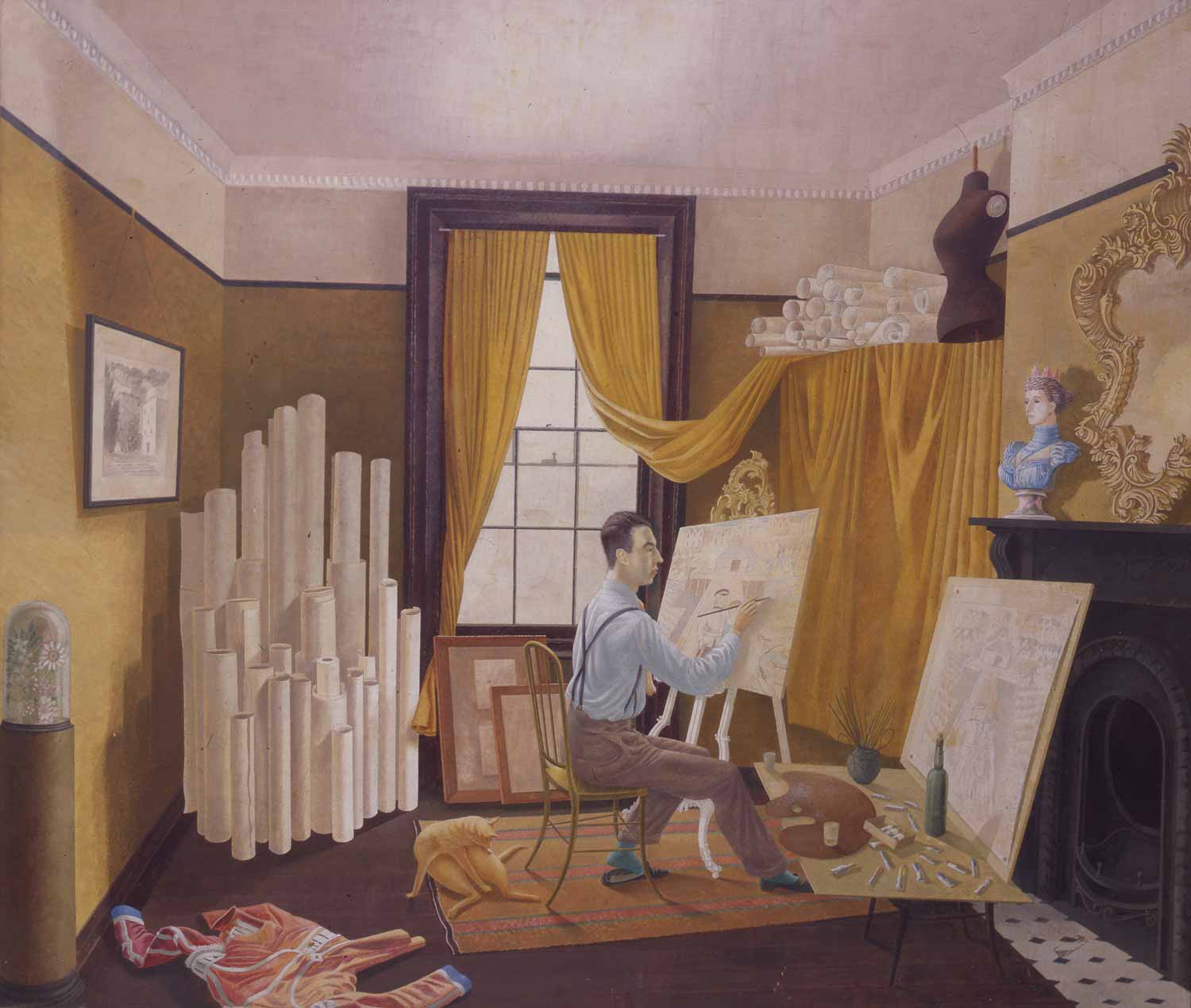

Another, younger set of notable artists all served in uniform in World War II. I have written here about Rex Whistler (1905–1944), that master of whimsy and fantasy, who joined the Welsh Guards when the war began, waited more than four years to go into action, landed in Normandy, and was killed by a German mortar shell on his first day under fire. He was a couple of years younger than Eric Ravilious (1903–1942), who expressed his romanticism in naturalistic watercolors in a style almost antithetical to Whistler’s imaginary landscapes and aristocratic fêtes champêtres.

Two recent exhibitions have testified to Ravilious’s enduring popularity. A retrospective two years ago at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in south London became one of the most popular exhibition in that excellent gallery’s two hundred-year history, and it was followed by “Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship,” seen first at the Towner Gallery in Eastbourne, the resort town on the Sussex coast where Ravilious grew up (and where Claude Debussy is said to have composed “La Mer”), and now at the Millennium Gallery in Sheffield. The show is accompanied by Andy Friend’s book of the same name, which gives a fascinating slice of English artistic and social history.

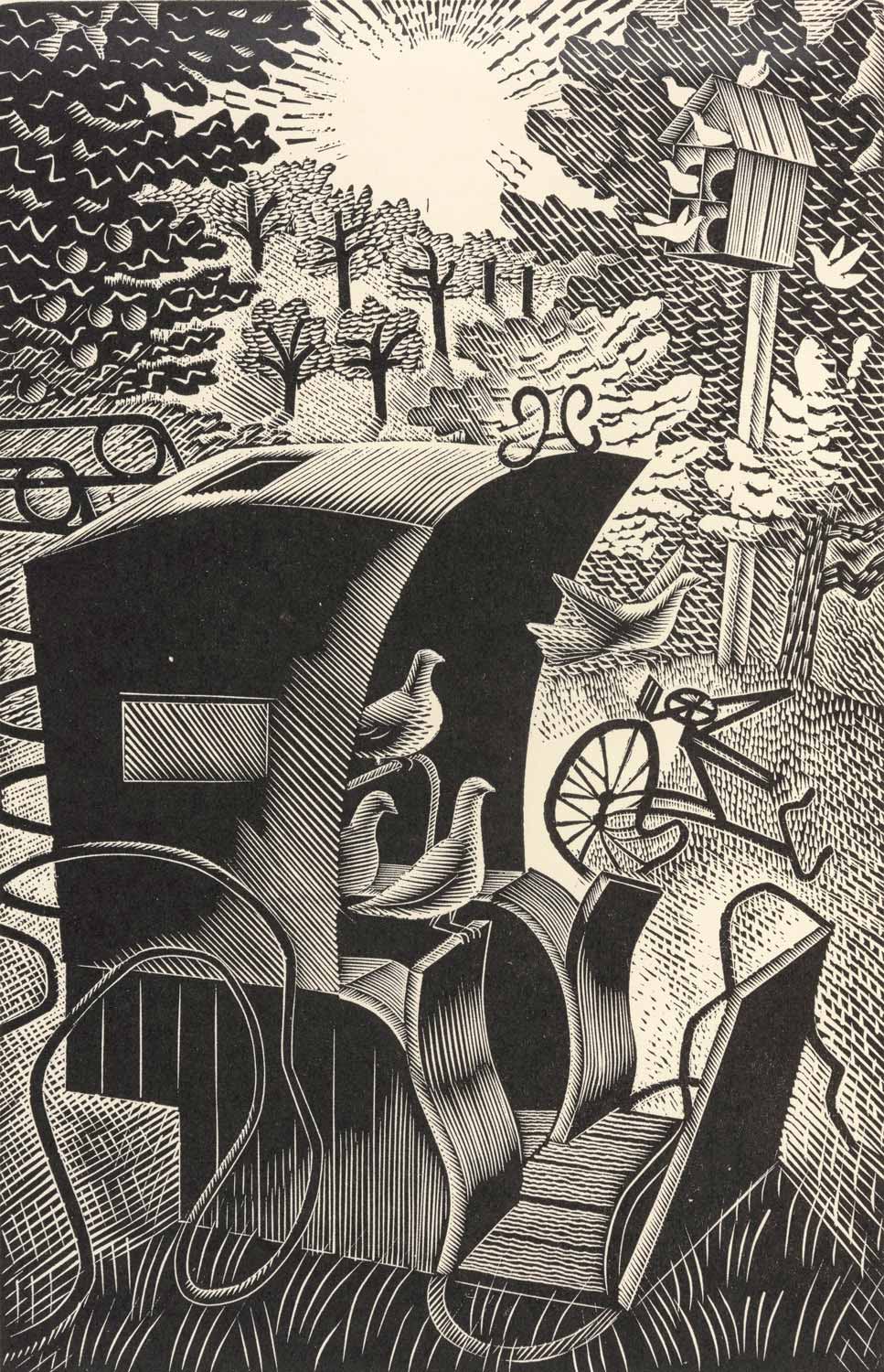

A lower-middle-class boy (“not quite a gentleman,” thought Tirzah Garwood when she met him, although she still married him), he made his way to the Royal College of Art and soon developed remarkable skill as a draughtsman and wood-engraver. He became a prolific and successful painter, but also an illustrator of posters and murals for exhibitions. Like every one of the artists mentioned in this article, he designed book jackets—and there’s a subject for an exhibition. Their work helped to create a golden age of London publishing and book production between the wars, and there are many hundreds of jackets that are worth seeing for their own sakes (and are often more memorable than the books they wrapped).

Advertisement

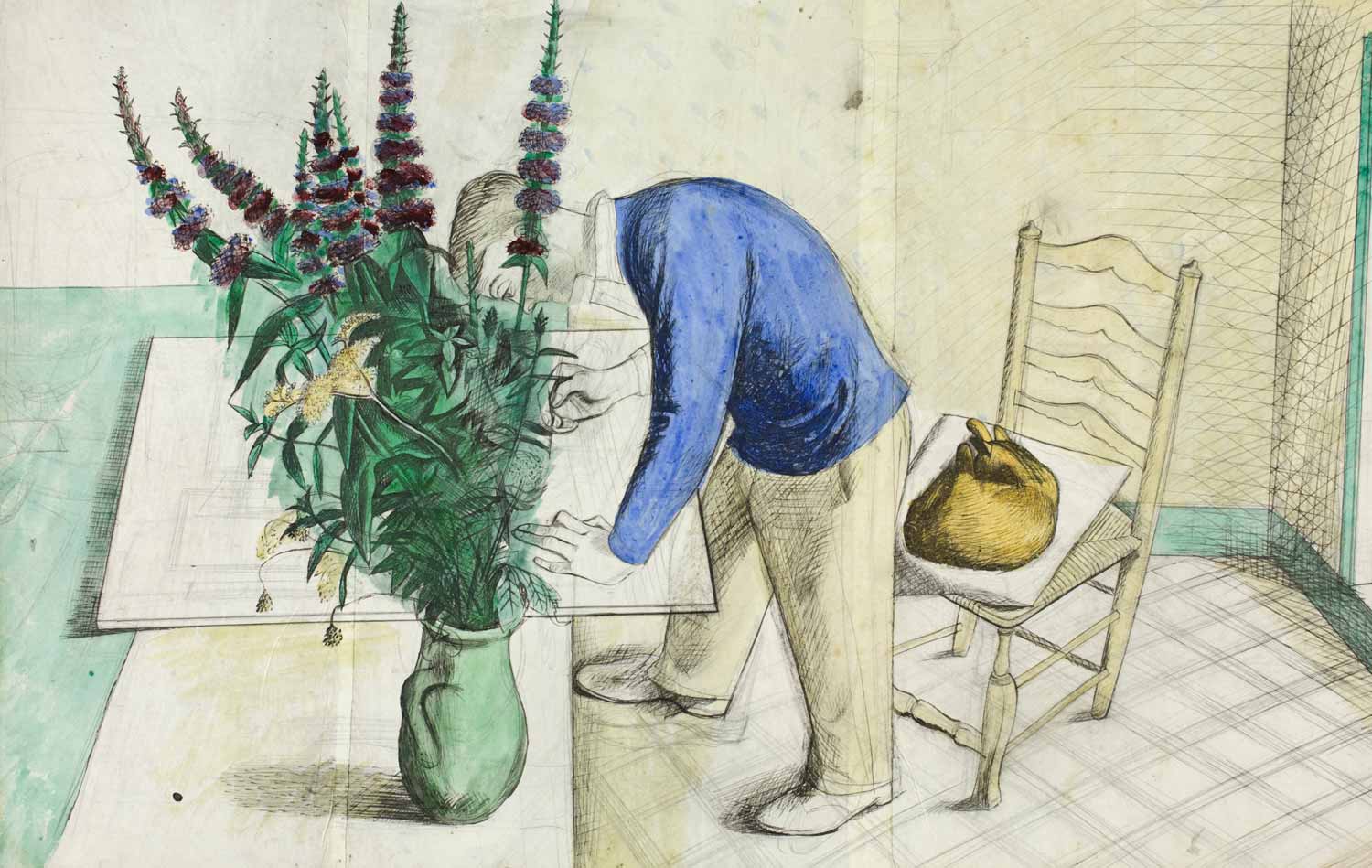

As its title suggests, “Ravilious & Co.” is about a group of friends and lovers. One of those friends was Edward Bawden (1903–1989), whose life was intertwined with Ravilious’s, and who will be commemorated by another show at Dulwich from May 23 to September 9, 2018. Although Furlongs, the Sussex cottage where Ravilious and other artists often stayed, was near Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s at Rodmell, and her family’s place at Charleston, there was little connection, and not much in common, between the Ravilious gang and the Bloomsbury set. The former mostly hadn’t been to public schools or Cambridge, and their plebeian high spirits make a pleasing contrast to the well-heeled narcissism of Bloomsbury. But the two groups were alike in one respect: their penchant for complicated romantic entanglements. In the later 1930s, Ravilious was torn between his wife, Tirzah, and Helen Binyon, his mistress (her word), both gifted artists themselves.

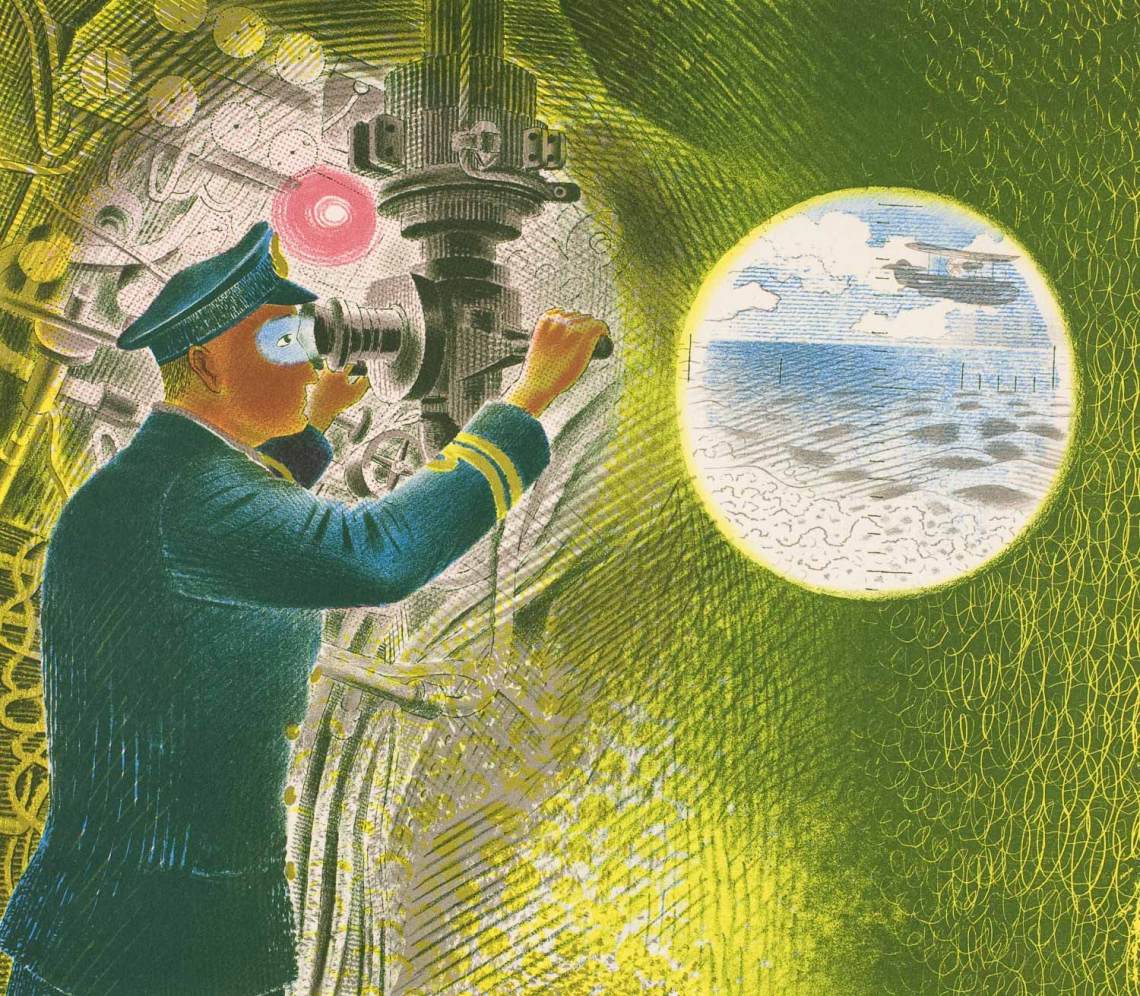

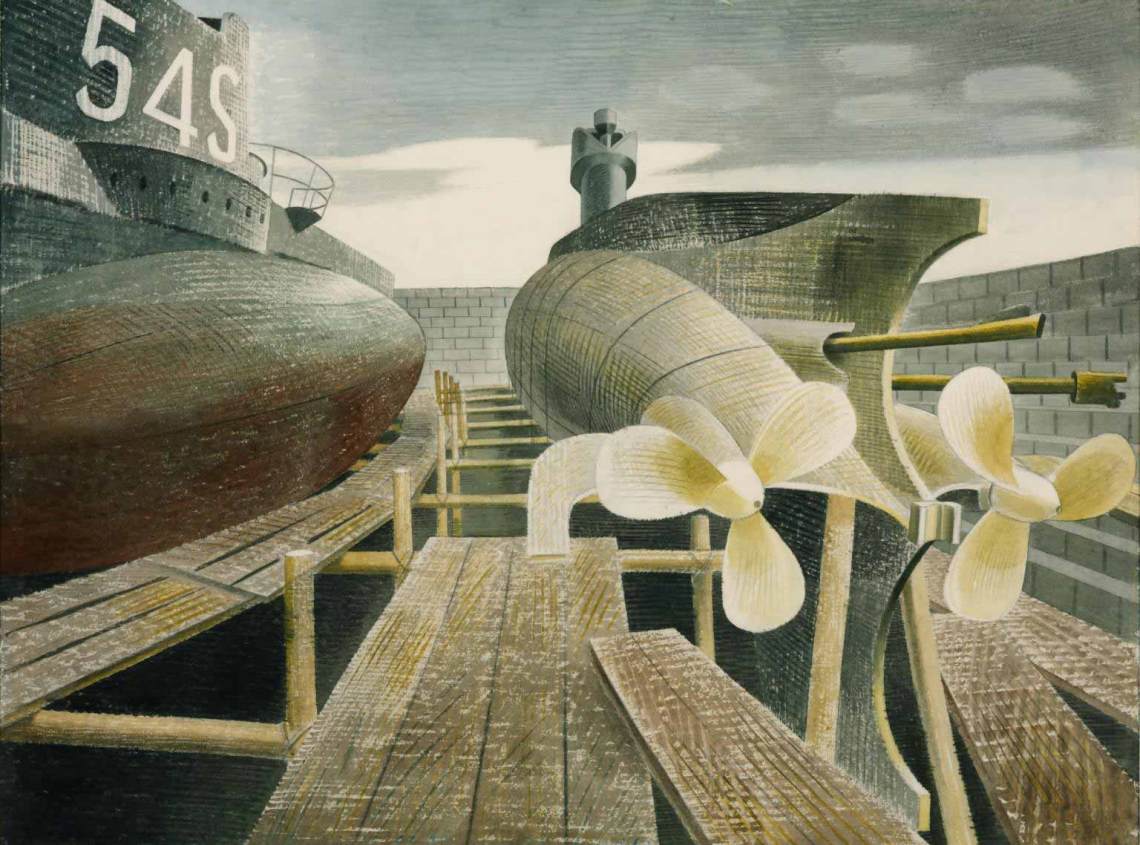

In 1940, Ravilious became an official war artist under Kenneth Clark, who led the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, as James Stourton described in his fine recent biography of Clark. A photograph shows Ravilious with his friends and fellow artists Barnett Freedman and Nash in army khaki, looking as though they were planning an infantry attack rather than talking about painting. Bawden was also a war artist, and his wartime work will certainly be an attraction at the forthcoming show. The skill with which Ravilious had depicted railways and ferries was now bestowed on warships and military aircraft: he portrayed an aircraft carrier in action or the interior of a submarine with rigorous attention to detail. Then he was sent to Iceland, which the British had occupied to pre-empt the Germans and to conduct an air war against the U-boats. In September 1942, Ravilious took off from Iceland in an RAF Hudson. Aircraft, crew, and passenger were never seen again.

When Ravilious died, the twenty-four-year-old John Minton (1917–1957) was serving briefly in the army. He had initially registered as a conscientious objector but changed his mind, was drafted, and in 1943 was commissioned in the Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry—surprisingly, given his fragile temperament. His military service ended shortly afterward when he had a breakdown and was invalided out.

Born during World War I, Minton grew up in middle-class comfort: his grandfather was a managing director of D.H. Evans, a large department store, and left Minton with independent means. Later in his too-short life, the artist would pass the store late at night with carousing friends, shouting from the taxi window, “We’re spending your money, darlings!” After art school, where he was befriended and influenced by the sculptor Michael Ayrton, Minton was a little aimless until the war. His generation had to escape from the thrall of Picasso, and what had already been called neo-Romanticism offered a way out. Minton’s early paintings are self-consciously experimental, but his gift was for realism—and once war came, he was soon drawing vivid pictures of the East End, which had been damaged during the Blitz. He was also an accomplished stage designer, and he and Ayrton designed Macbeth for John Gielgud in 1941.

In a recent exhibition of his work at Pallant House, the label for one nocturnal wartime scene alluded coyly to Minton’s “promiscuous relations with passing sailors.” But this is a sad story. Minton seems at once to have accepted his sexual identity and been tormented by it: “I am sexually as queer as anyone you are likely to meet,” he told Ayrton. “I wander about the streets on the summer nights feeling desperate and pick up any boy that would have me. It was all there in my paintings.” (I own a pretty pen-and-ink drawing by Minton given to me by my friend Clare Moynihan. Her late husband, the journalist John Moynihan, was the son of two painters, Rodrigo Moynihan, and Elinor Bellingham Smith; Smith told her daughter-in-law Clare that she was the only woman Minton had ever been to bed with: “I may have put him off for good.”)

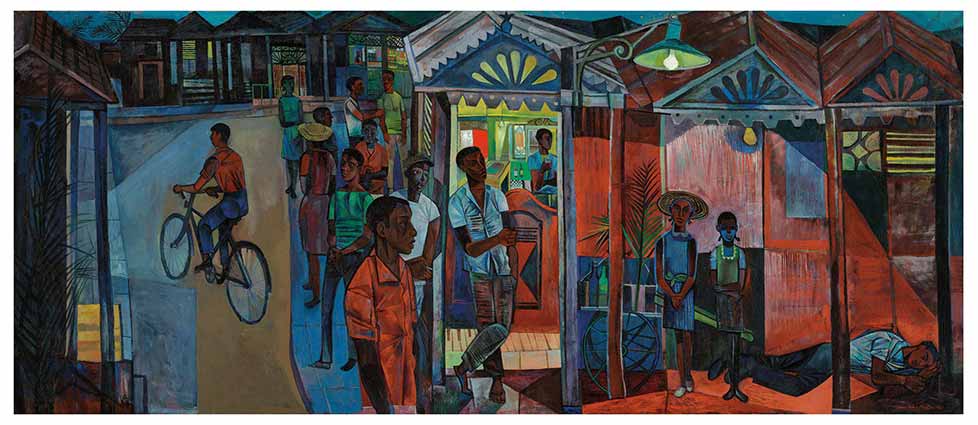

And yet, Minton could also say that his work demonstrated “that weakness, lack of incisiveness which characterizes all the self-expression of homosexuals.” His pastoral drawings gave Minton one means of escape from that torment, and Landscape with a Harvester Resting (1944) unmistakably echoes Samuel Palmer, that wholly original genius of nineteenth-century English art. But Minton yearned to get away from England, a yearning so often found in that time of Blitz and blackout (see Cyril Connolly’s magazine Horizon). The warm south beckoned once the war was at an end. “It’s a sort of drug, travelling,” said Minton, and in the postwar years he drugged himself by visiting Spain, Italy, Morocco, and even Jamaica (the paintings he made there have been acclaimed as the works of a genius cut short; this seems exaggerated).

Minton’s handsome, gaunt appearance was itself fascinating, and there were three portraits of him at Pallant House: a photograph by John Deakin, a self-portrait, and a portrait by his friend Lucian Freud. The contrast between the last two shows the difference between someone who wasn’t a great painter and someone who was. In truth, Minton was a minor painter but a fine illustrator. In 1947, he and the journalist and poet Alan Ross visited Corsica and collaborated on a travel book, Time Was Away, with text by Ross and drawings by Minton. His next project was illustrating Elizabeth David’s first two books, A Book of Mediterranean Food and French Country Cooking, helpfully anticipating those two abiding passions of the postwar upper middle class, fine art and fine food.

By a sorry coincidence, all three of these later neo-Romantics—Whistler, Ravilious, and Minton—died at the age of thirty-nine, the first two in the war, Minton by his own hand.

Why, then, do these artists speak to us so strongly still? The critic Peter Conrad sneeringly dismisses Ravilious and Bawden as artists whose “homespun provincial anecdotes pastoralized the country” with a “villagey vision… insulated from the modern world.” That misses a point about the contemporary appeal of such pastoralism perceptively made by the writer Ian Jack at the time of the Dulwich Ravilious show. He wondered whether those watercolors’ “endearing but unsentimental depiction of southern England, in particular, doesn’t explain a good part of Ravilious’s appeal to people who otherwise struggle with the idea of Englishness: meaning, it sometimes seems, almost any Englishman or Englishwoman to the left of… [the former UKIP leader] Nigel Farage.”

It is worth noting that in the angry Thirties, Ravilious’s friends stood mostly on the left and they saw no contradiction between their politics and a love of rural beauty. Ravilious expressed his own kind of patriotism through wood-cut vignettes—for example, in a series of booklets for London Transport called “Country Walks,” or in his cover illustration of top-hatted Regency cricketers for the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack (printed annually for sixty-five years until barbarously discarded).

There is a palpable mood of nostalgia in England at present. This may have been expressed politically in Brexit, but it is also visible in the popular taste for “heritage” and lost worlds. In particular, Britain is awash with books and films about World War II, which all these painters lived through and which became part of their artistic legacy. The England that Ravilious and Bawden evoked so powerfully reflected neither reactionary sentiment nor aimless aesthetic ideals. Their rural vision was not about an escapist rural retreat or nostalgic nationalism, but about a precious common heritage, something worth fighting for.

“Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship” is at the Millennium Gallery in Sheffield through January 7, 2018 and will then be on view at the Compton Verney, Warwickshire, from March 17 through June 10, 2018.

“John Minton: A Centenary” was at the Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, earlier this year.

“Paul Nash” was at the Tate Gallery earlier this year.

David Jones: Vision and Memory” was at the Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, in 2015 through 2016.

“Ravilious” was at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2015.

Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship by Andy Friend is published by Thames & Hudson.

John Minton: A Centenary by Simon Martin and Frances Spalding is published by Pallant House Gallery.

The Art of David Jones: Vision and Memory by Ariane Bankes and Paul Hills is published by Pallant House Gallery and Lund Humphries.

Romantic Moderns: English Writers, Artists and the Inanition from Virginia Woolf to John Piper by Alexandra Harris is published by Thames & Hudson.