I was terrified of Chris Ware’s new book, Monograph, and when it landed on my doorstep, I found my fears well-grounded. The book arrived in a huge box, twenty-two inches square by four inches tall (I measured it). As Ware fans will know, this is not his first big and tall book. Before Monograph, there was Building Stories. Nor is this the first to demand extraordinary things from the reader.

To open up and examine any of Ware’s productions, even some of the small ones, you need a clean, well-lighted surface that you can crawl over, nose to page, as well as fantastic eyesight, plenty of patience, and a good bit of courage. For Ware’s new tome is, in essence, a grand tomb in the Egyptian mold, whose contents will tell anyone who breaks into it what this person’s life was like. It seems almost an invasion of privacy to enter this crypt.

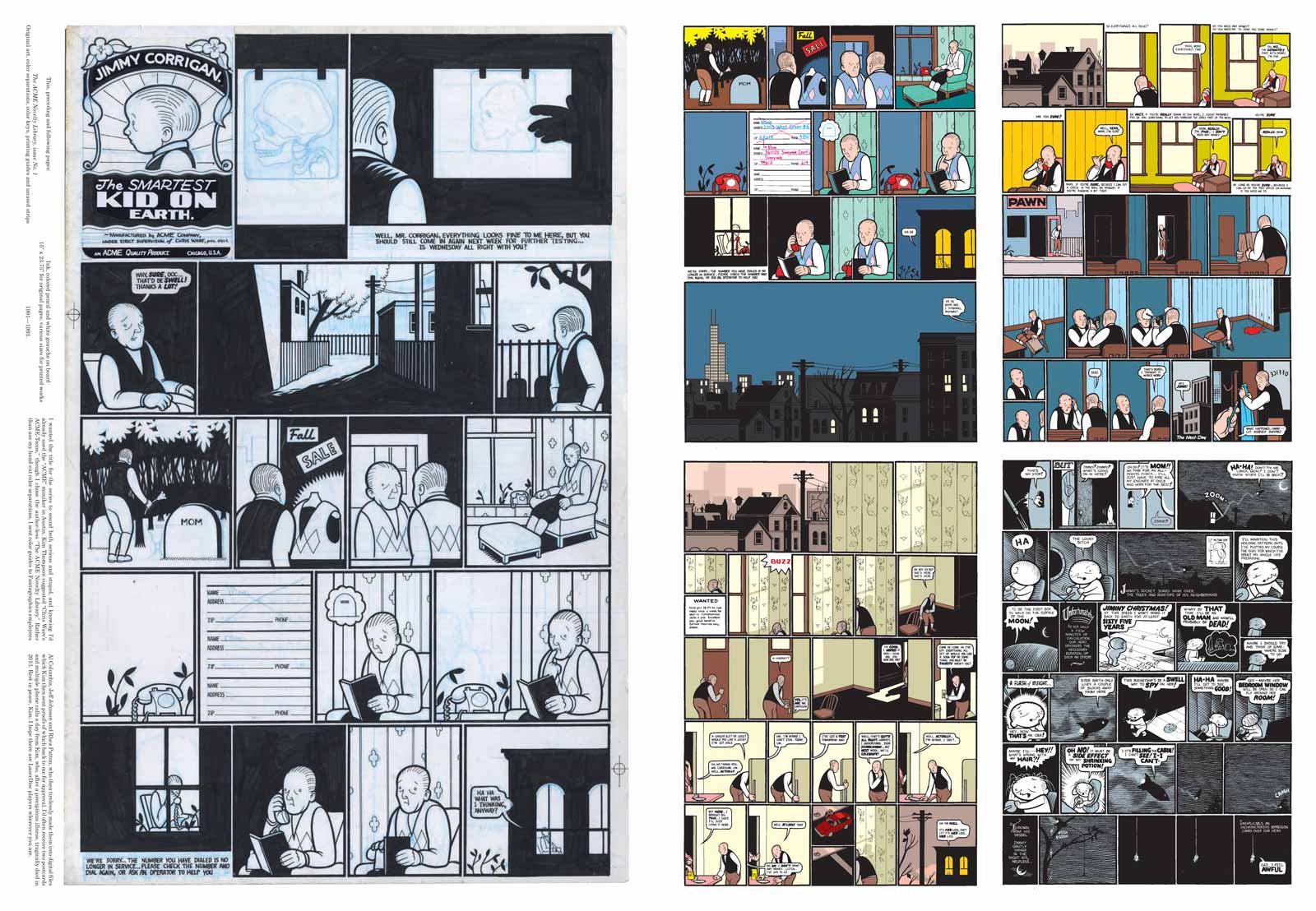

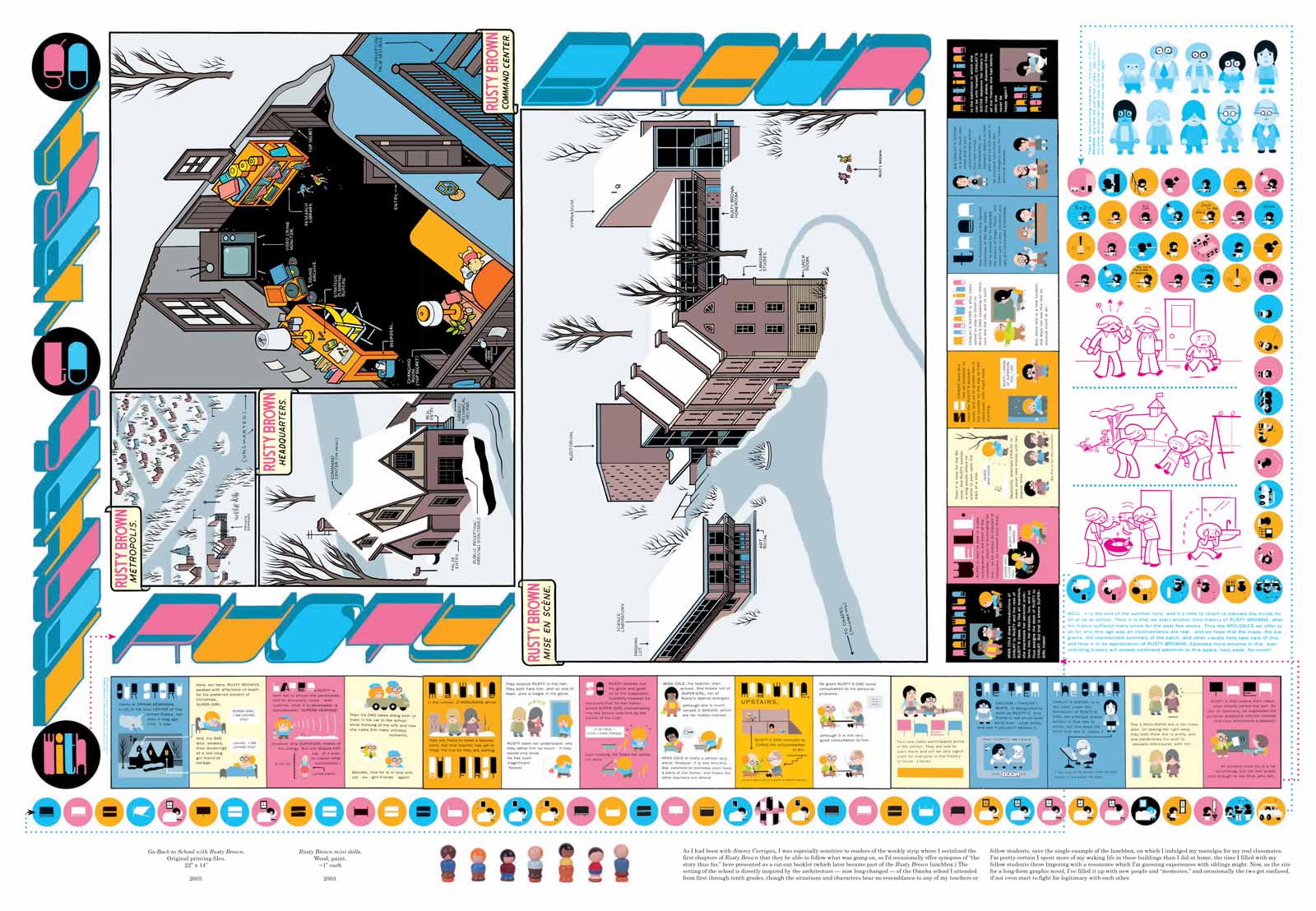

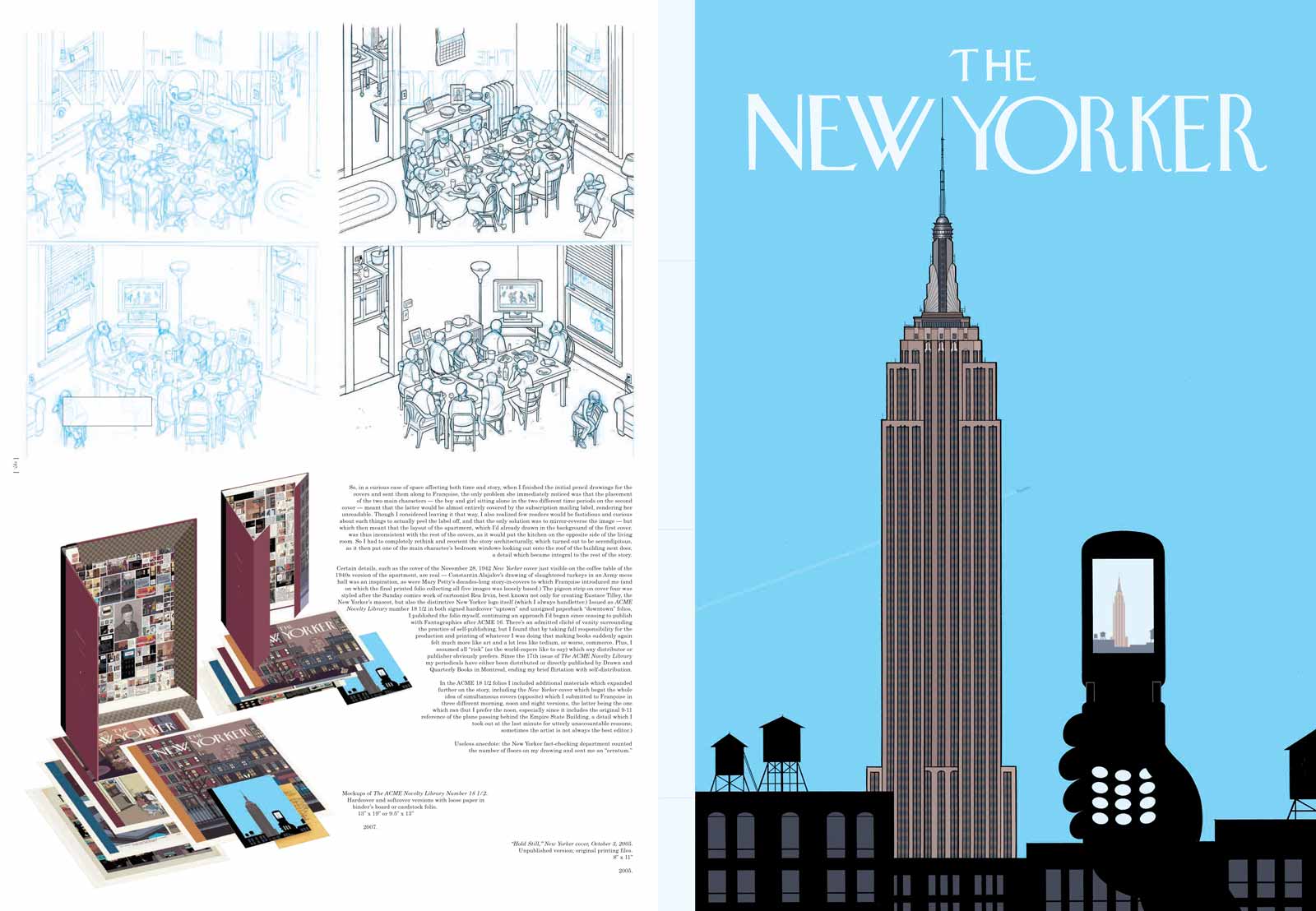

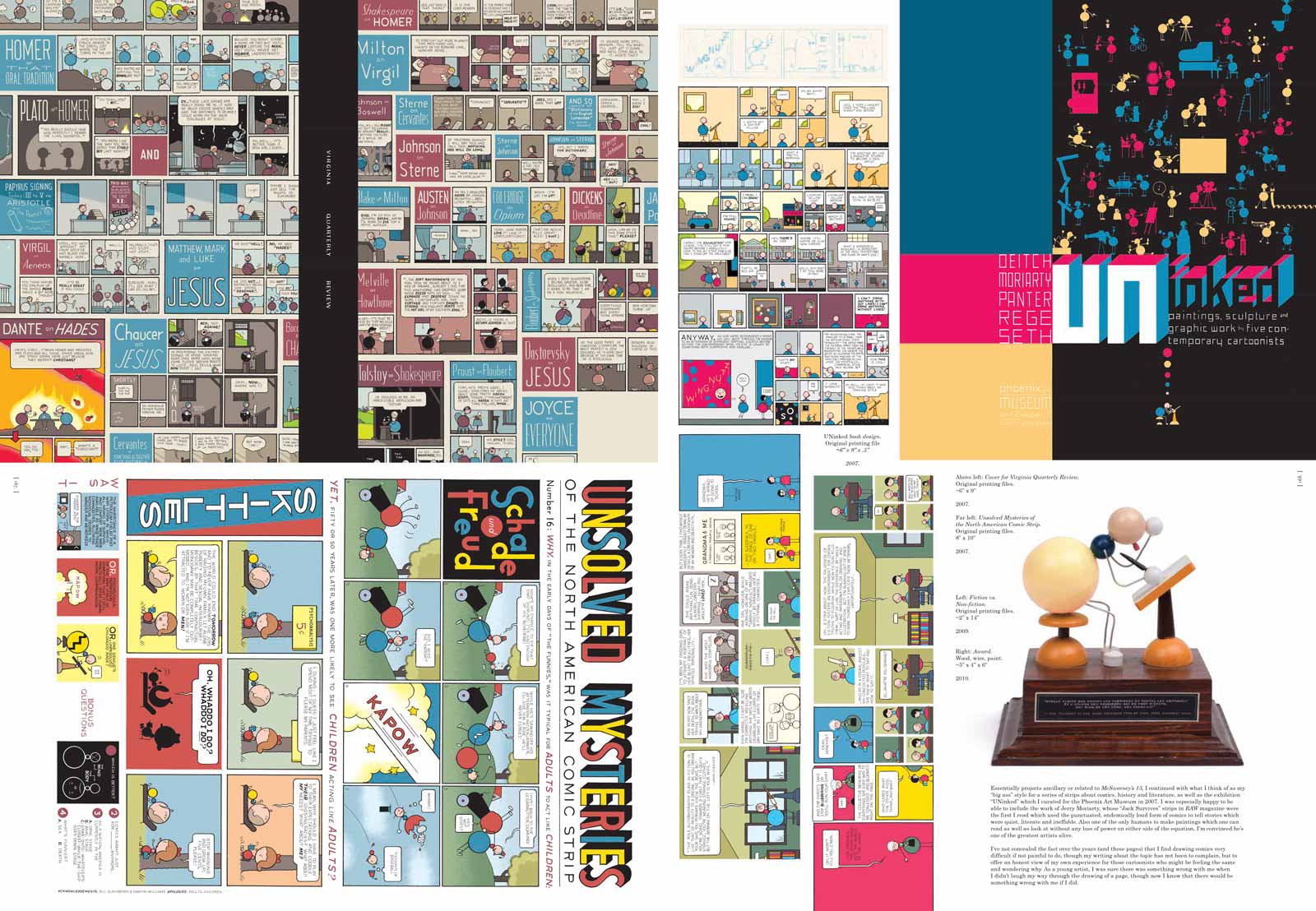

Monograph contains multitudes: lists of books Ware has made; New Yorker magazine covers he’s drawn; pages of other cartoonists’ books (Krazy Kat and Gasoline Alley) that he has designed; printing files for his own books (including some for his best-known and saddest work, Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth); instruction sheets for cutting and folding his toy models; fake old-timey ads that he has mocked up; pages from his illustrated datebooks; life drawings from his college days; sketches and photographs of people he’s known, cities he’s loved, and kitchens he has drawn in; pictures of toys and contraptions he has created, including a wooden book dispenser that he used to fill with tiny comics and a zoetrope that he built because “I knew I’d never be able to afford to buy one.”

And that’s not all. As I fanned through the 275 numbered pages of the book, I noticed my fingers catching, pausing, at all the little booklets he stapled or glued inside Monograph. As I blindly patted down each page to make sure I wasn’t missing any, I counted seven. The first (and my favorite) is a loosely drawn ’zine, “Impressions of the Nursing Home Where My Grandmother Was for the Last Few Months of her Life.” The second is one of Ware’s “Acme Novelty Comics” devoted to some of Jimmy Corrigan’s early adventures. There is a small photo album from a book party, tiny sheet music for a musical composition, “Farewell,” and a comic called “Clara.” Another object, a miniature manual, “Banjo Method,” is part of the Rusty Brown story. The last booklet is an “abandoned episode” from Ware’s comic “The Last Saturday.”

Monograph is not only, as its title suggests, a deep dive into one subject, Chris Ware, but is also, as Art Spiegelman notes in his introduction, Ware’s own “cabinet of wonders” and “a guided tour of the inside of his head and what has come out of it…” It lays out the primal sources of his material, too: his obsession with missing fathers, his fascination with superheroes and superhero toys, his images of men on crutches (to escape a locked room, he once jumped out of a building at the Art Institute of Chicago, breaking both legs), and his fixation on building interiors. The prose is deadpan, which you’d expect, and ponderous, which makes you marvel anew at Ware’s visual economy. The tone is bleak, ingrown, and retrospective, or, in Spiegelman’s words, “suffused in nostalgia for his own past and the past that preceded it.”

With tiny type and lavish illustrations, Ware, who apologizes for including so much personal material, tells the story of his life:

I was born in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1967. Omaha could easily be considered the most midwestern of midwestern cities; it’s the middle of the country, the middle of the culture, the middle of the road. Not surprisingly, I grew up middle class, the result of a brief marriage between my mother, Doris Ann Ware McCall (b. 1943) and submarine sailor Michael Bruce Haberman (1943–2000) whom I didn’t meet until I was an adult… Raised by my mom with the help of my grandparents and especially my grandmother Clara Louis Ware (1905–1990) I lived a perfectly happy and contented and safe childhood…

The one missing detail: a father.

It was this bitter seedling—and Ware’s one brief meeting with the father who abandoned him as a kid—that grew into his multi-generational tale of Jimmy Corrigan, the tragedy of a stunted loner, his childhood, the disappointing father figures who cross his path, and their own trail of disappointments. An example: when middle-aged Jimmy’s long-lost father makes him breakfast for the first time, it is with rashers of bacon spelling the word “HI.”

Advertisement

Ware and his artistic mother—he says she still draws a better horse than he does—lived for most of Ware’s childhood with his maternal grandparents. His grandfather, whose hair was the model for that of the adult Jimmy Corrigan, always wanted to be a cartoonist but never made it. But it was Ware’s grandmother, Weese, short for Louise, a woman whom he describes as “sharp, funny, and empathetic,” who dug the deepest groove into Ware’s psyche. She is everywhere in his work, and the passages about the end of her life are his finest writing. This grandmotherly kernel, which he has in common with Proust, is something I did not know about Ware before reading Monograph.

As a child, Ware was fascinated by mail-order illustration classes (something he has in common with Charles Schulz) and would spend hours drawing at his grandmother’s table. He was also obsessed with television and comic-strip superheroes, and with old family photo albums, which, he writes, “imbued me with the strangest sense that the world of the past was all still there but just out of my reach, hidden somehow behind a curtain of—something; and then, behind another curtain, the unknowable, but still inevitable certainty of the future.”

Not long before Ware started college at the University of Texas at Austin in the late 1980s, he moved to San Antonio, Texas, with his mother and her third husband. His grandmother followed. Clearing out the family home in Omaha, Ware writes, left him “confused and unmoored.” He knew it was good for him, that he should “live in the moment.” But this upheaval, he said, left him with a question that is fundamental to his work: Which is more real? “The long-ago moment itself or its enduring memory?”

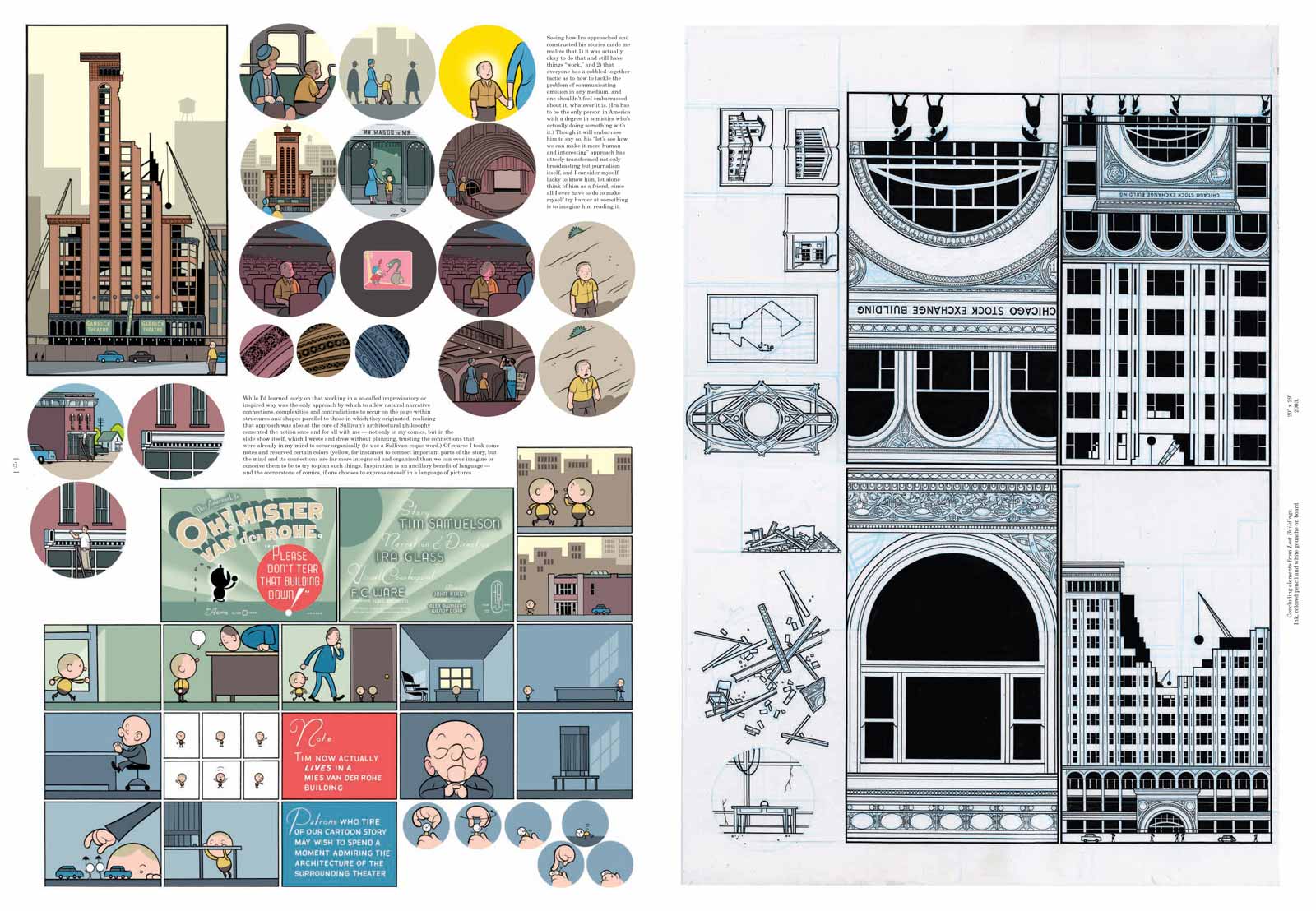

In Texas, Ware was torn between the reality of his dying grandmother and his ordinary college existence, and he bridged those worlds by making objects. For instance, he built a sort of dollhouse, a “cabinet in memory” of his grandmother’s house. And once he realized that his grandmother was too sick to visit him in Austin, he made her a ten-inch by eight-inch by eight-inch diorama of his apartment.

Ware also drew comics. His first success for the college newspaper, The Daily Texan, was a loosely drawn potato-shaped creature, inspired, as he says, by “George Herriman, Robert Crumb, Kaz and Charles Burns.” At a certain point, Ware altered the potato’s face by jabbing out its eyes, and the comic strip thus came to be called “Waking Up Blind.” It is loose and strange, one of my favorites, and very different from the more mechanical, clear-line style I associate him with. Ware himself grudgingly recognizes its merit: it “was the largest color comic strip I’d ever drawn, and the first, once it was done, that I decided was possibly good.”

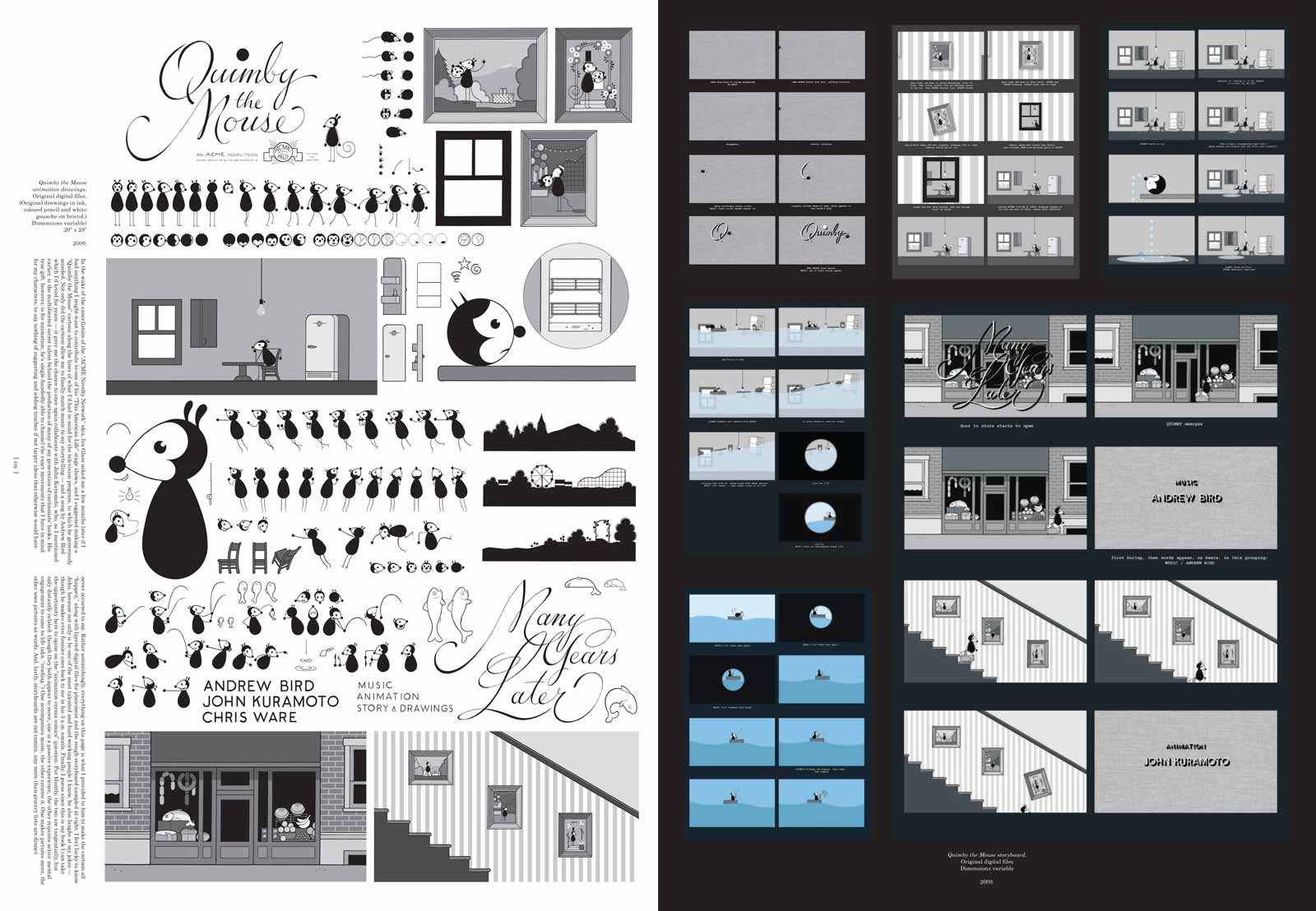

After the potato head, Ware experimented with “cartoon faces created more or less by drawing Mickey Mouse without ears” and created a “strip about a lone pale character lost in a landscape of nostalgia.” Members of the Black Student Alliance found the earless Mickey, who looked liked a minstrel, racist—a conclusion Ware shamefacedly agrees with. The strip got pulled from The Daily Texan until he supplied the mouse creature with dog ears. Although this version did pass and get published, Ware still sees in it “privileged white middle-class blindness” to the “pervasiveness of racism in American visual culture.” He cringes “in humiliation.” But he didn’t stop making the mouse.

Ware’s big break came in 1987. “I picked up the phone… and the voice on the other end of the line claimed to be Art Spiegelman,” the author of Maus, who edited RAW with his wife, Françoise Mouly. Spiegelman, Ware recalls, had “seen my student strips on the back of a review of Maus in the University of Texas paper.” It was, Ware recalls, like getting a call “from Paul McCartney or John Lennon.”

Advertisement

For his RAW debut, Ware produced a colored version of “Waking Up Blind.” For his second RAW comic, he resuscitated his Mickey-ish mouse for a strip called “I Guess,” which was the first time that he used text that was “seemingly unrelated to the strip’s images” and threaded it “through balloons, titles and panels in a manner which felt poetically analogous to how words and images coexisted in my own consciousness.” This was one of Ware’s great strokes of originality and the beginning of Quimby, who would become the star of Ware’s book-length project Quimby the Mouse and one of Ware’s most affecting alter egos.

As Ware developed Quimby, his grandmother began to die, and Ware saw her decline from the live-wire she had been—before they moved out of her house in Omaha, they had a “booze dumping party” to finish off all the bottles left in her house—to a woman who was losing her hold on reality, watching phantom “doors opening on the ceiling above her hospital bed.” She, who had been almost a part of him, was breaking “into pieces and fading away.” Quimby, apparently a stand-in for Ware, briefly “morphed into a two-headed character.” And at last, when Weese died, in 1990, the second head broke off and Quimby resumed his one-headed life. Knowing the background to this moment makes it all the more moving.

After college, Ware moved from Austin to Chicago and began studying printmaking at the Art Institute of Chicago. But, he says, “I was (and still am)… not only incapable of producing a well-made image, but also suffer sheer panic at the sight of a fresh-grained lithographic stone.” So he began “messing with the xerox machines.” By this time, he had also racked up a shelf of influences, including Joseph Cornell, Jim Nutt, George Herriman, Charles Schulz, Frank King, Kaz, Ivan Brunetti, and Philip Guston. It was during a snowy walk in Chicago that the story of Jimmy Corrigan was hatched.

In 1992, Ware began drawing for the weekly newspaper NewCity; his strip was called Acme Novelty Comics and included some early renditions of Jimmy Corrigan. This was when his comic style moved from being loose, like Krazy Kat, to being more tightly controlled, like Barnaby and Gasoline Alley. When he saw his first comic published in NewCity, he remembers, “I felt like a character in a Broadway musical who’d just gotten his ‘big break,’ literally launching myself into a jumping run on State Street.” But he then stresses how shameful his elation is to him: “Though it sounds seriously pathetic now, I like to keep this humiliated memory of my young optimistic self hydrated… ”

Ware has a deadpan self-abnegation that is, by all accounts, genuine. But in such an enormous book as this, which is fairly bursting with photographs of his accomplishments and friends, and all the amazing drawings documenting his rise from lonely, fatherless child to fifty-year-old genius, it does seems a terrific struggle to keep the humble pie hot through 275 pages. About halfway through, Ware’s aw-shucks attitude became, at least for me, hard to take:

In 2001 I was nominated for, and inexplicably received, the Guardian First Book Prize for the UK edition of Jimmy Corrigan, which Zadie Smith had won for White Teeth the year before… Anyway, Zadie and I have remained friendly ever since and to this day I don’t understand why a writer of her caliber, intelligence and humanity would even bother to give me the time of day.

Well, he needn’t be so abashed about all he has done. But, then again, that painful shame is part of the production; it is also his fuel and part of the reader’s experience. Indeed, as I was trying to read the maddeningly minuscule type, which he may have chosen out of modesty, it suddenly occurred to me that such shy typography, so key to his work, actually demands an awful lot from the reader. The smaller the type is, the closer the reader must come, crawling to the heart of him.

Françoise Mouly, Ware’s friend and editor at The New Yorker, notes in her introduction to Monograph that there is truly humbleness in Ware, which is basic to his work: “the humility of his grand project,” she writes, is in pinning down “the butterflies of our most basic but universal emotions… how we relate or fail to relate to each other, how we inhabit our homes and apartments.” But as humble as Ware’s project is, when you spread it out on the table or floor, it is also quite grand, indeed as grand as many of Ware’s recent productions.

This is the paradox of Chris Ware. Yes, it is truly an embarrassment to have put so much work into the lonely excavation of one’s own navel and one’s navel’s navel’s past. But after all, there is no cartoonist on earth who does this better—or with more economy and subtlety—than he does. At the young age of fifty, Ware has, with this tome, prepared himself a beautiful tomb for the day when he finally dies of embarrassment.

All images are from Monograph by Chris Ware, published by Rizzoli.