In the summer of 2009, a slender novel caused a literary sensation in Moscow. Centering on a poetry-loving gangster-cum-book publisher wracked by Hamletian perplexities over a possible snuff film, it unloaded a darkly absurdist, but caustically knowing, satire on the corruptions and machinations of post-Soviet Russia, with a whirligig of literary remixes and references.

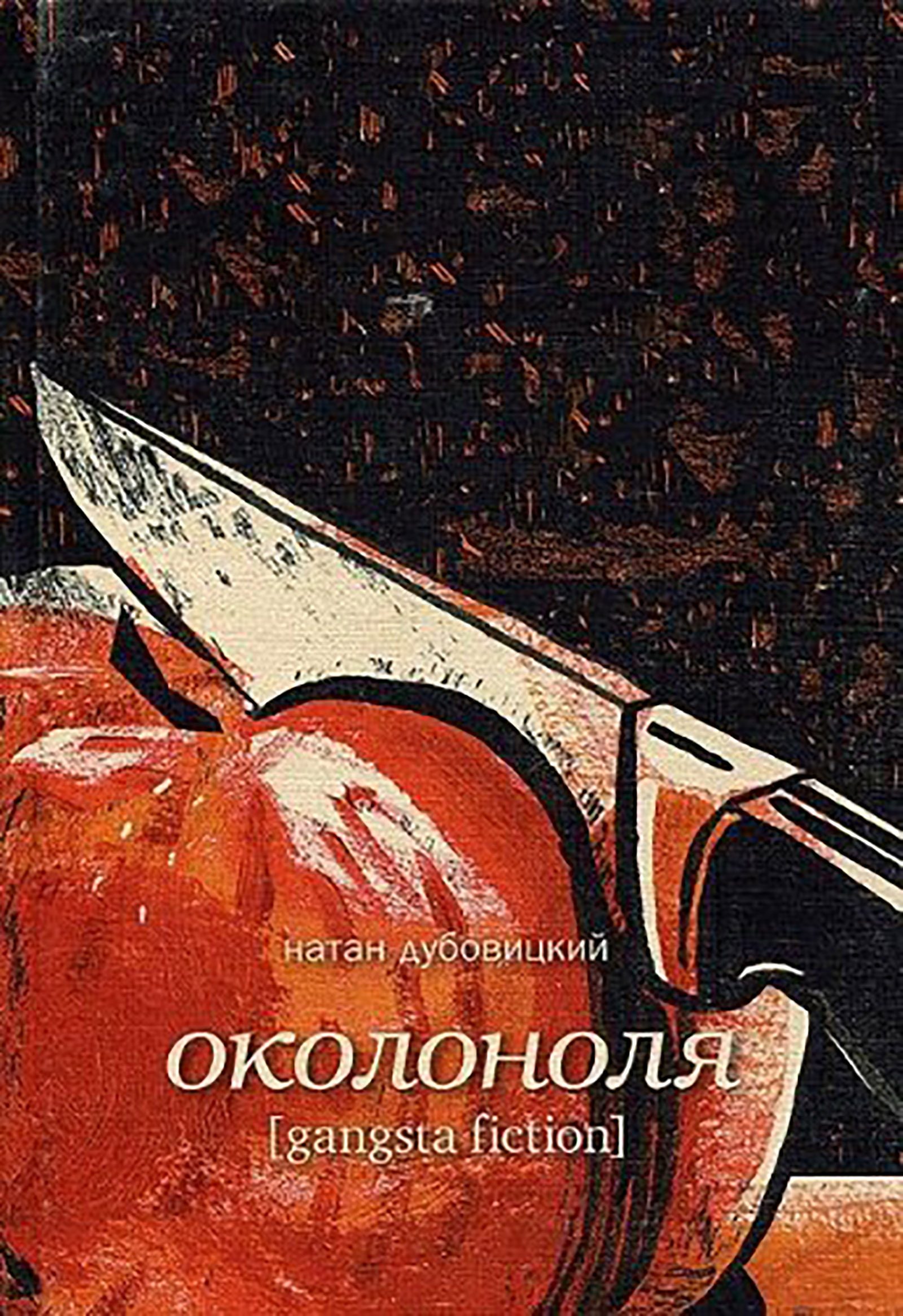

What really triggered the sensation, though, over Okolonolya, or Almost Zero (subtitled gangsta fiction, in English, in the Russian edition), was the identity of its author, an unknown named Natan Dubovitsky. Dubovitsky was soon suspected, courtesy of an anonymous tip from the novel’s publisher to the St. Petersburg newspaper Vedomosti, of being a pseudonym for Vladislav Surkov, who was then the Russian presidential deputy chief of staff. At the time, this Kremlin ideologue was, arguably, the second- or third-most powerful man in the country. It was Surkov, variously called a “political technologist,” the “gray cardinal,” or a “puppet master,” who had created and orchestrated Putin’s so-called sovereign democracy—the stage-managed, sham-democratic Russia, the ruthlessly stabilized, still-rotten Russia that Almost Zero was savaging. Almost Zero is now available to English readers in a limited edition from an adventurous small publisher in Brooklyn, Inpatient Press. Inpatient takes the leap and credits Surkov as the author. (And, in the spirit of Almost Zero itself, it is publishing the novel without authorization.)

Plenty of politicos write novels; but not many write eviscerating self-satires. It was as though Karl Rove had taken the knife to his and George W. Bush’s America in, say, 2005. Surkov, however, wasn’t, and isn’t, simply a Rove. The documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis calls him “a hero of our time” (in praise and opprobrium) for turning Russia’s political reality into “a bewildering, constantly changing piece of theater.” For supplying an early model, if you will, for Donald Trump’s media-savvy tactics of chaos and confusion. And what a perversely fascinating, complex figure emerges from the details of Surkov’s biography: an arch-propagandist of power and an arty outsider, an authoritarian’s right hand and a bohemian aesthete whose education included studying theater at the Moscow Institute of Culture in the 1980s (he was expelled for fighting). As the USSR was collapsing, Surkov became the public-relations mastermind for oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s pioneering business, Menatep Bank, which was where Surkov met his wife, Natalya; soon, he was heading up Russia’s fledging association of ad men. Denied a partnership in business after Khodorkovsky’s ill-fated acquisition of the oil giant Yukos in the 1990s—Khodorkovsky ended up in prison during Putin’s taming of the oligarchs—Surkov left for a position with Alfa Bank (of Trump dossier notoriety, for alleged aid in Russian meddling in the 2016 election; the owners are suing for defamation). He then ran a major TV network, before devoting his image-making and lobbying talents, first, to then President Boris Yeltsin, and, subsequently, to Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev.

Even in government, Surkov found time to write essays praising Bollywood movies and Joan Miró in the pages of Russian Pioneer, a glitzy intellectual magazine—which went on to publish Almost Zero in a special edition. He composed lyrics for the Russian rock band Agata Kristi (whose lead singer later sued a critic for calling him “a trained poodle for Surkov”). Famously an admirer of Tupac Shakur, Surkov can also quote Allen Ginsberg’s poetry by heart, albeit in heavily-accented English (there’s a cringe-making recording online of him reciting Ginsberg’s “Supermarket Sutra” in full). In his spacious Kremlin office, photos of Putin and Medvedev hung beside the likenesses of Jorge Luis Borges and John Lennon, Che Guevara and a young Joseph Brodsky, together with Tupac in a hoodie, Obama looking pensive, and Bismarck looking “Iron Cross.”

Tall, in tailored Zegna charcoals, with looks suggesting a dashing upgrade of Rowan Atkinson, the shadowy Surkov was considered a creative genius. Especially by himself. His tragedy, wrote journalists Zoya Svetova and Yegor Mostovshchikov in a seminal profile in Russia’s New Times magazine, was to imagine himself smarter and better than his bosses—even though “he is always in supporting roles.”

In 2005, Surkov’s persona gained a new layer of complexity when he revealed in an interview with Der Spiegel that his father was Chechen. Contrary to his official biography, Putin’s gray cardinal had lived his first five years in a village near Grozny. He was born Aslambek Dudayev in 1962 (or 1964); his Russian mother renamed him with her maiden name soon after his father deserted the family in Chechnya, and mother and son moved to western Russia. Identity-shifting came early to the future puppet-master. Duba-Yurt, the village where he spent those first five years, was later bombed into oblivion during Russia’s ferocious wars against Chechen separatists. It is a typically Surkovian paradox that he would go on to become the main advocate in Putin’s circle for Ramzan Kadyrov, the Chechen strongman and former rebel leader who has turned into a crucial ally of Moscow, keeping Islamist extremism in check in the Caucasus region he rules with an iron fist. A 2007 appraisal of Surkov by the global intelligence firm Stratfor called him “utterly ruthless and extraordinarily and pathologically opportunistic.”

Advertisement

Meanwhile, Surkov denied being Natan Dubovitsky in Russian Pioneer itself, when the allegations of authorship arose, and coyly denies it to this day—even though his wife Natalya’s maiden name is Dubovitskaya. Such apparent, almost obvious pranking (some commentators suggested Surkov was himself the source of the anonymous tip to Vedomosti) brings to mind what Adam Curtis sees as a feature of Surkov’s political tactics: that he let it be known what he was doing—for instance, officially backing human-rights NGOs even as he guided and funded anti-NGO, pro-Putin youth groups—“which meant that no one was sure what was real or fake,” as Curtis put it in his 2016 documentary HyperNormalization.

*

Almost Zero opens with someone reading aloud a story he’s selling—one of the various brief stories and poems that sprout, unrelated, throughout the novel—a story that at one point plagiarizes Jorge Luis Borges’s trope of a character unwittingly writing an exact copy of an existing book (in this case, by the early-twentieth-century Soviet dystopian satirist Yevgeny Zamyatin). This scribbler, what’s more, is a werewolfish madman named Victor O.— a clear tweak of Victor Olegovich Pelevin, one of the prominent Russian satirists whose works have been vilified in street actions by the pro-Putin youth groups supported by Surkov. Right away, then, we’re being signaled that literary games are to be Almost Zero’s bread and butter. The novel’s forty-six short chapters are awash with allusions—name-dropped, riffed on, played with, co-opted.

The buyer of the Victor O. story is the “gangsta” of Almost Zero’s subtitle, a middle-aged, world-weary ex-bookworm named Yegor Samokhodov. Yegor has gotten rich thanks to writing having become a lucrative commodity in the wild days after the USSR’s fall. Armed gangs now fight over printed matter—old, new, or forged—like cartels warring over cocaine and heroin. There is a sharp satiric joke here that blends the late-Soviet veneration of culture with post-Soviet oligarchic looting.

Yegor is thus a publisher as drug dealer, and wielding a gun is part of his business arsenal. We see Yegor making his rounds: browbeating a vodka-sodden poet for verses to supply to a client, the regional governor, to publish as his own; conducting business in a sauna with a religiously obsessed hitman who collects brief literary works; contracting with an aging actress-turned-scribbler in her bubble bath while various young terrorists, both Russophile and jihadist, engage in bomb-making and theological disputes that flare into a Tarantino-style standoff of drawn weaponry.

Given Almost Zero’s assumed author, the reader plays detective, perhaps a tad feverishly, for evidence of a confessional roman à clef, clues about the “gray cardinal.” Some obvious ones turn up, as in Yegor’s sideline as a PR operative—bribing a journalist to renounce a story critical of his governor client, arranging phony political debates on television. Yegor is also described as being “perhaps the first in his lilywhite, rhythmless country to hear the curse words in the lyrics of American rappers.” And then there’s Yegor’s richly evoked provincial Russian childhood, which seems to match Surkov’s, post-Chechnya, as do Yegor’s unpartnered mother and his strong grandmother (here, a beloved moonshine-maker named Antonina Pavolvna, “like Chekhov”).

And what about Yegor’s name? Is it really too feverish to suspect a subtle evocation of Yegor Gaidar, the author of the hated capitalist “shock treatment” to the post-Soviet economy that devastated most Russians’ lives—but which, its defenders claim, stabilized the chaotic country? Surkov likes to credit himself (and Putin) as Russia’s stabilizers, too.

Almost Zero is one of those loaded works that tease and entangle the reader not only with deciphering literary references—daunting for a non-Russian: Is the name of Yegor’s publishing gang, the Blackbookers, meant to invoke the Black Book that detailed Soviet Jewish victims of the Nazis?—but also with references to the author’s world. Should Almost Zero be considered a literary prank or part of Surkov’s wider political-social machinations? Or is the novel simply a virtuosic display of his notorious self-regard? Igor Fedorovich, chief of the Blackbookers, apostrophizes Yegor thus: “You are indifferent and undaunted by everything, because everything around you is insignificant and meaningless. Only something truly grandiose can enchant you. Something so huge that perhaps the entire world will seem tiny.” Perhaps this is Surkov talking to the mirror.

Advertisement

Eventually, Yegor will come to wrestle with a hunger for vengeance for the gruesome, mysterious fate of his faithless girlfriend, Crybabe, and a dire ordeal of his own—pitted against a yearning to renounce his life of guns and greed. His wrestlings will be conspicuously presented, if you please, as remixes of soliloquies from Hamlet. While this is going on, Wall Street’s banks will collapse, sending Russia’s system of corruption collapsing as well around our Hamletian gangsta and his fellows. “Pirated Mallarmé or legal Lermontov,” we’ll be informed, “did not sell.” (Some commentators read this as Surkov’s warning to the country’s larcenous powerful in the wake of the Great Recession; in 2009, Surkov was working at the Kremlin for then-President Medvedev and his liberalizing economic agenda.)

Almost Zero closes with a showdown between Yegor and a maniacal nemesis, although whether it’s real or imagined by Yegor is unclear. What is clear is the pastiche of Humbert Humbert’s revenge scene in Lolita. Some obliging Russian reviewers gushed over the language of Almost Zero as “Nabokovian.” Well, not exactly, in the English translation by Nino Gojiashvili and Nastya Valentine; but the writing is savory and spirited, and sometimes lyrical; the tone mordant; and the satire acute. Occasional passages of genuine emotion are balanced against a requisite dose of Russian cynicism. “It’s exactly the sort of book,” noted Peter Pomerantsev in the London Review of Books, the Russian-born British journalist and Surkov’s main chronicler in English, that “Surkov’s youth groups burn on Red Square.”

*

Russian reviews of Almost Zero ranged from awestruck to contemptuous. The ultra-nationalist pro-Putin film director Nikita Mikhalkov, who made Burnt by the Sun, hailed the novel as “a truly great and amazing book… a masterpiece… a book we have not been seen since The Master and Margarita.” But another reviewer, in Russian Pioneer’s own pages, sneered that “the author clearly has nothing to say. So he clowns. There is nothing under all his paraphrases, retellings and rehashings… It’s a quasi-novel, a doll or a scarecrow.”

That critic was, naturally, Vladislav Surkov himself, writing under his own name. Shortly afterward, he changed his mind and declared—at a Russian Pioneer public event—that Almost Zero was “a wonderful novel.” He had not, he averred, read anything better. So which review, in Adam Curtis’s words, was real and which was fake? Quite a tangle of thorns, as Humbert Humbert might say. In a further twist, in 2011 Almost Zero was adapted into a Moscow stage production by director Kirill Serebrennikov, a darling of the avant-garde. Surkov showed up in the audience. (Today, Serebrennikov faces highly dubious corruption charges; his controversial ballet about Nureyev premiered recently with him under house arrest.)

*

In 2011, a second Dubovitsky novel appeared, Mashinka and Velik, the nicknames of two murdered teenagers in the story. This novel, too, caused a sensation. One well-regarded critic called the book a devastating depiction of a Russia that preys upon its children. Still not copping to authorship, Surkov rhapsodized to an interviewer: “I think it’s the last book that I read in my life. I won’t read anything else. I can’t… The others don’t compare.” This novel is not yet available in English.

Then, in early 2014, amid Russia’s black ops in eastern Ukraine and Crimea, Natan Dubovitsky published a jarring dystopian sci-fi short story, “Without Sky.” This has been translated into English on various websites. The story describes World War V, the new “non-linear” style of war of the twenty-first century, a conflict staged among multiple, confusing, shifting alliances. Physical combat is only a phase of this warfare, but it has obliterated the sky from the narrator’s village. Or has rendered the village’s survivors capable only of two-dimensional consciousness. All is yes or no, black or white. And these 2-D survivors, the narrator warns, will come seeking their revenge on the city that refused them shelter.

It’s an eerie, disturbing tale—all the more so since we have reason to believe it is the maestro of non-linear operations in eastern Ukraine and Crimea himself who is relating the story, through the victims’ voices. Is “Without Sky” another twisted element in this non-linear strategy?

Surkov was demoted to run economic affairs in 2011, after protests against Putin’s third presidency rendered the public-relations stratagems of “managed democracy” outdated, to be replaced by blunt-force repression. Strangely enough—or true to form—Surkov called the protesters “among the best people in Russian society,” adding that he himself was “too odious for this brave new world.” In 2013, he resigned from the government under a corruption cloud (he was later exonerated), and went fishing with Kadyrov in Chechnya. But Putin soon brought him back as a special assistant on Ukrainian matters, and his involvement in the annexation of Crimea led to his being named in the US’s Magnitsky sanctions list in 2014. These days, Surkov is in American news as Putin’s envoy in talks with the US over eastern Ukraine. In Russian news, Surkov’s estate in a gated community of oligarchs and big shots outside Moscow has become a target for the guerrilla anticorruption reporting organized by the opposition leader Aleksei Navalny. In a video that Navalny produced, which has been widely shared on the Internet, Natalya Dubovistskaya, Surkov’s wife, can be seen with her girlfriends at a garden party where everyone is wearing Marie Antoinette costumes and wigs.

So how is an English reader to approach Almost Zero? I asked some Russians for advice. The author and journalist Masha Gessen hadn’t read the book. “Should I?” she wondered. I told her I thought Surkov was fascinating, apparently very smart. “None of them are smart,” she said. Pussy Riot’s Maria Alyokhina looked taken aback when I brought up Almost Zero during audience questions at her performance with the banned Belarus Free Theatre at New York’s La Mama. “I have no interest in reading it,” she replied. “I don’t think I will.” Understandably, perhaps, since Surkov was in charge of the government’s religious relations when Pussy Riot’s members were imprisoned for their punk song performance in Moscow’s Christ the Savior cathedral in 2012. I emailed the novelist Vladimir Sorokin, whose outrageous satires, like Pelevin’s, have been attacked by the nationalist youth groups supported by Surkov. “Yes,” he wrote back from Berlin, where he now lives, “people say that it’s Surkov’s book, maybe it’s true. I’ve read twenty pages and that was enough for me. It’s secondhand literature. There is no space there, no air. Only effort and the attempt to write a ‘contemporary postmodern novel.’ It’s boring.”

I also received a reply from the filmmaker Adam Curtis. He said he hadn’t read Almost Zero, but was “very interested” to do so. He just wouldn’t be able to get to it for a while because he was too busy making a follow-up to HyperNormalization. In that film, Curtis drew a connection between Trump’s assaults on reality and the man who theatricalized Russian politics with a “ceaseless shape-shifting that is unstoppable.” That is the man who seems to have given us Natan Dubovitsky and his gangsta fiction.

—With translation assistance from Alexei Bayer