For four years, as a Peace Corps volunteer working on drinking water systems, I lived in some of Nepal’s remotest mountain villages, many days’ walk from the nearest motor roads. My love for 35mm black-and-white photography had deepened while in college and in 1975, before heading to Nepal, I purchased a Leica M3 camera which was then always with me. By 1979 I was slowly making my way back to the US. Living in Seoul for a few months was a way of readjusting to modern life. And it was easy enough for young Americans like me to make money teaching English.

At the time I was in South Korea, from September through December 1979, Seoul was a city on edge. One evening in October, the country’s autocratic president, Park Chung-hee, was gunned down at dinner with his cabinet by his own intelligence chief. It was unclear whether the assassination represented a coup attempt.

Soon, the city was full of South Korean troops—hours before the midnight curfew that had been imposed by the US after the end of World War II in 1945. The next day, somber Western-style martial music played on public address systems; there were tanks parked on the streets. Jimmy Carter sent a fleet of US Navy ships to protect South Korea.

A Hollywood movie happened to be in production in Seoul at the time—Inchon, about a pivotal battle in the Korean War—and every American guy I knew got work as an extra. We were all dressed in US Army battle fatigues with boots, helmets, and guns. Several hundred of us spent a day marching back and forth alongside Inchon Harbor.

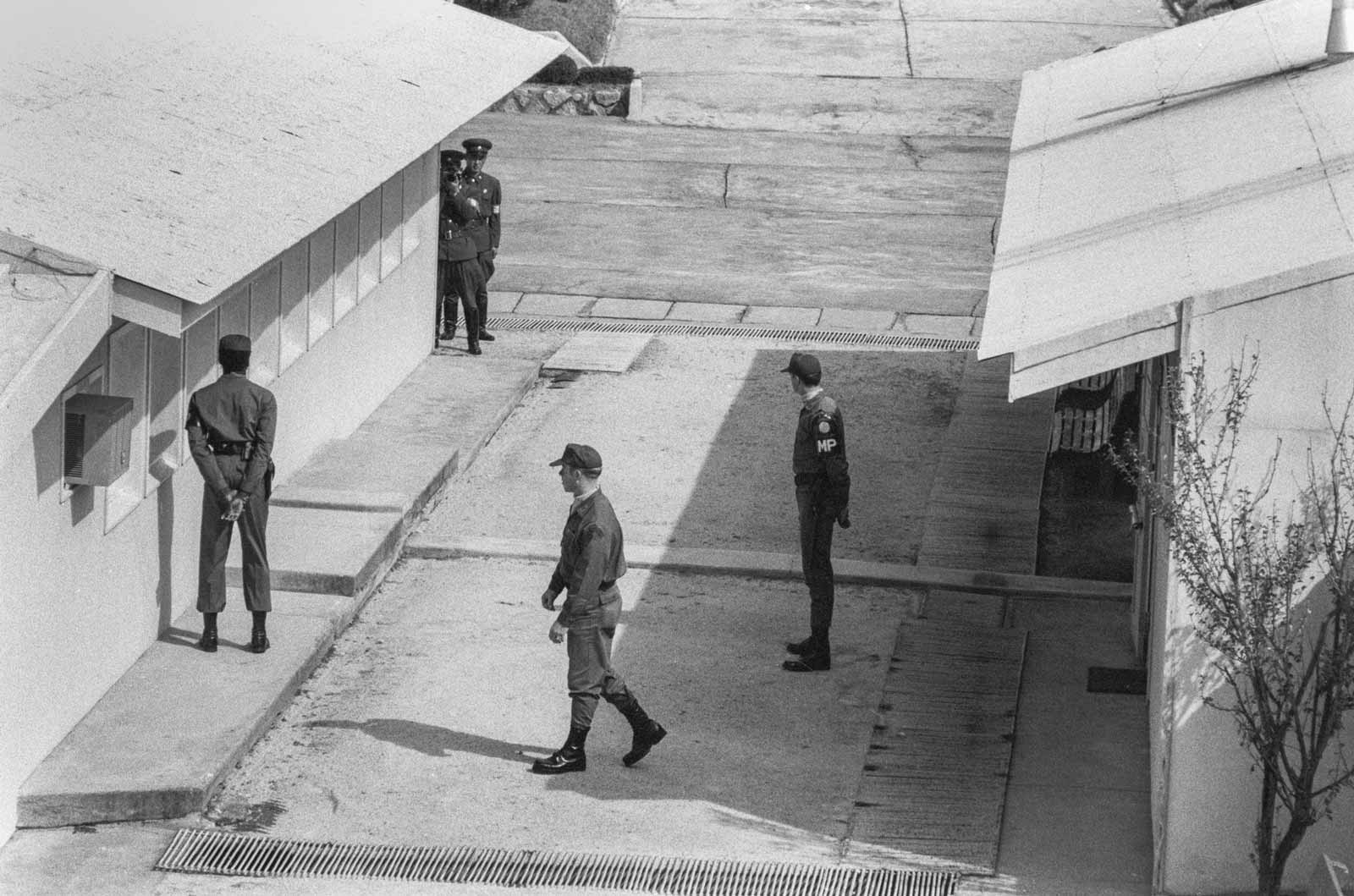

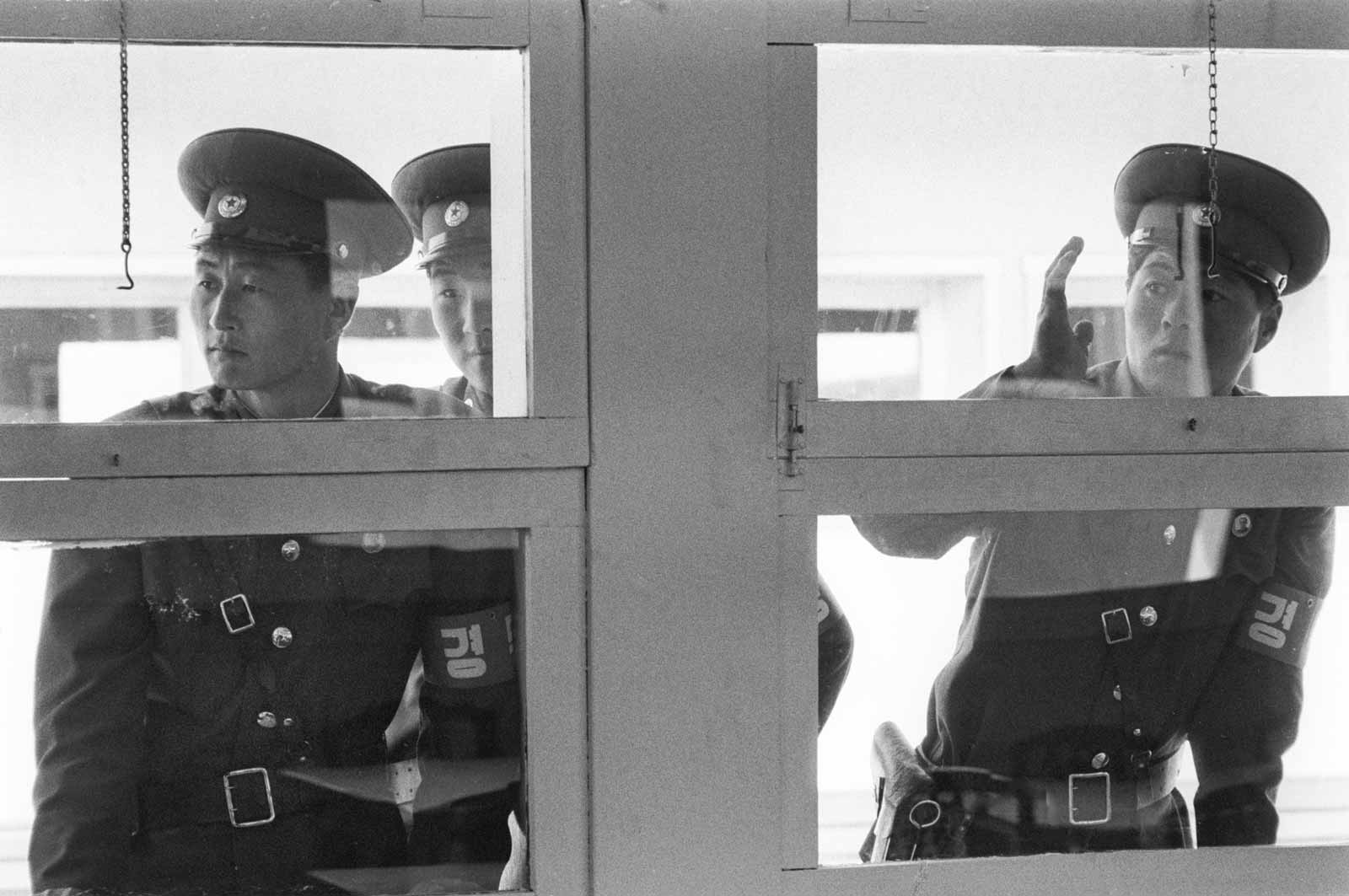

Every Saturday morning, the United Service Organizations offered a bus tour to the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). At a briefing beforehand, everyone had to sign a waiver freeing the US and South Korean governments from liability if anything were to happen during the visit. At the DMZ, we were admitted to a conference room that straddled the border. North Korean soldiers peered in at the windows.

My negatives from that day sat collecting dust on a shelf for nearly forty years. Seeing the images for the first time, I’m struck by the choreography of the soldiers on either side of the border; they seemed to be involved in an intricate dance of watching and being watched. There was a paradoxical intimacy to the encounter despite the great unknowing.

Today, the tension along the DMZ is as high as ever. Has anything changed?