One of the defining traits of 1980s New York City postmodernist writing and painting was the urge to deconstruct. This extended to the comics medium in Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s Raw, an oversized anthology magazine that serialized Maus and introduced readers to “art comics” from around the world. Spiegelman’s experimental work looked like exploded pages of Sunday cartoon battles between what was then considered “low” and “high” art. Richard McGuire’s short story “Here” dissected a single room across time using a panel-in-panel device also seen in 1980s painters like David Salle and Robert Longo. Gary Panter drew apocalyptic nightmares that dismantled and intuitively reconstructed drawing modes from Picasso to Jack Kirby.

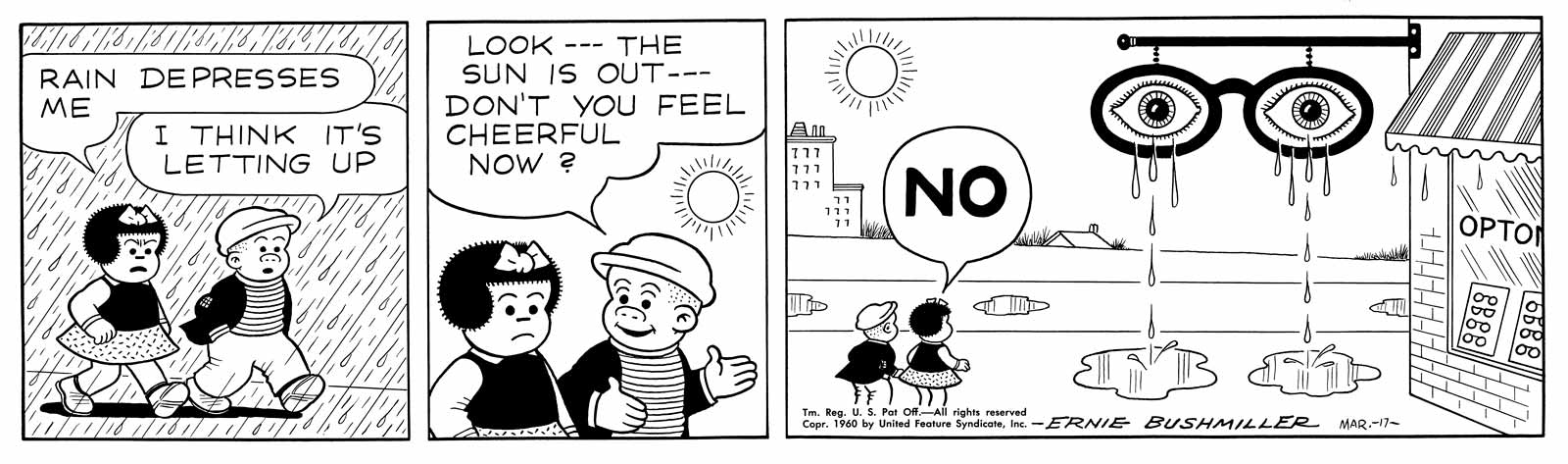

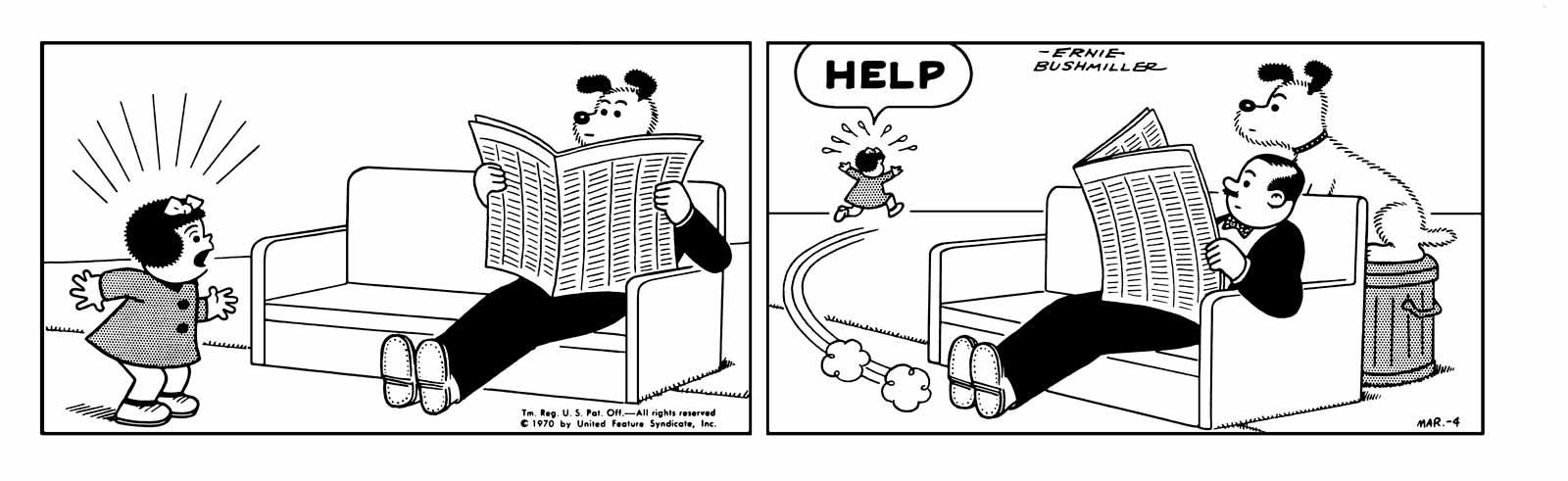

In the midst of all of this deconstruction was a renewed interest among cartoonists in a humble, plain-looking gag strip that began in the 1930s: Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy. Nancy follows an eight-year-old suburban girl as she solves mundane problems and interacts with Sluggo, a fellow prankster and sometimes romantic interest. Bushmiller (born in 1905) drew it for most of his life, with each strip as a self-contained “gag”—a single joke that could be easily digested as the reader glanced across the strip. The imagery and jokes are so prototypical and simple that the American Heritage Dictionary uses it to illustrate the meaning of “comic strip.” The appeal of Nancy to the art comic crowd might seem counter-intuitive, but while Nancy was never particularly clever, it was always cleverly constructed. In fact, the accomplishment of Nancy, with its refined, reduced lines and preoccupation with plungers and faucets, might primarily be a matter of form. As Bill Griffith (Zippy the Pinhead, also Raw) wrote in his 2012 introduction to a collected Nancy volume: “Nancy doesn’t tell us much about what it’s like to be a kid. What Nancy tells us is what it’s like to be a comic strip.”

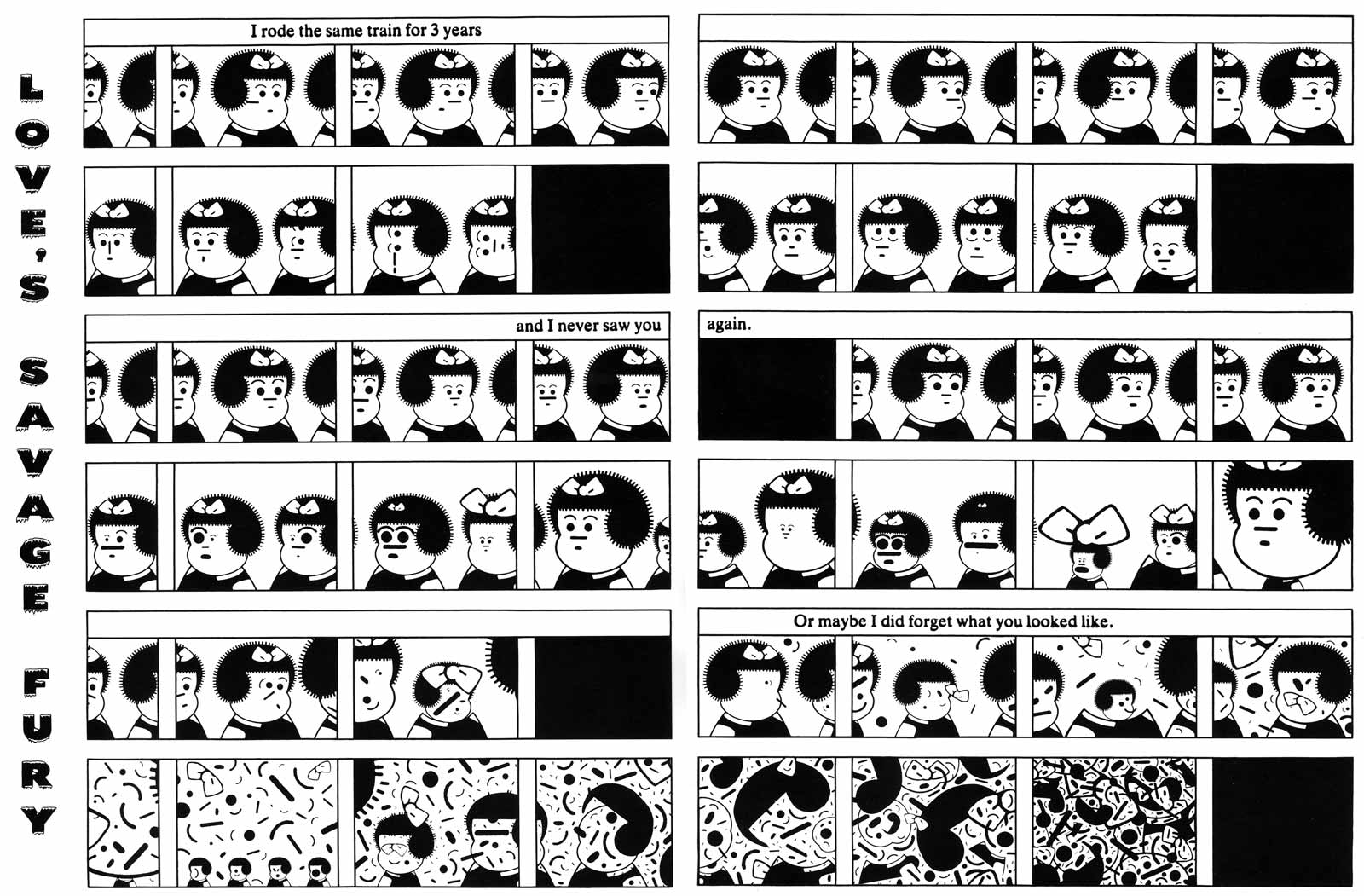

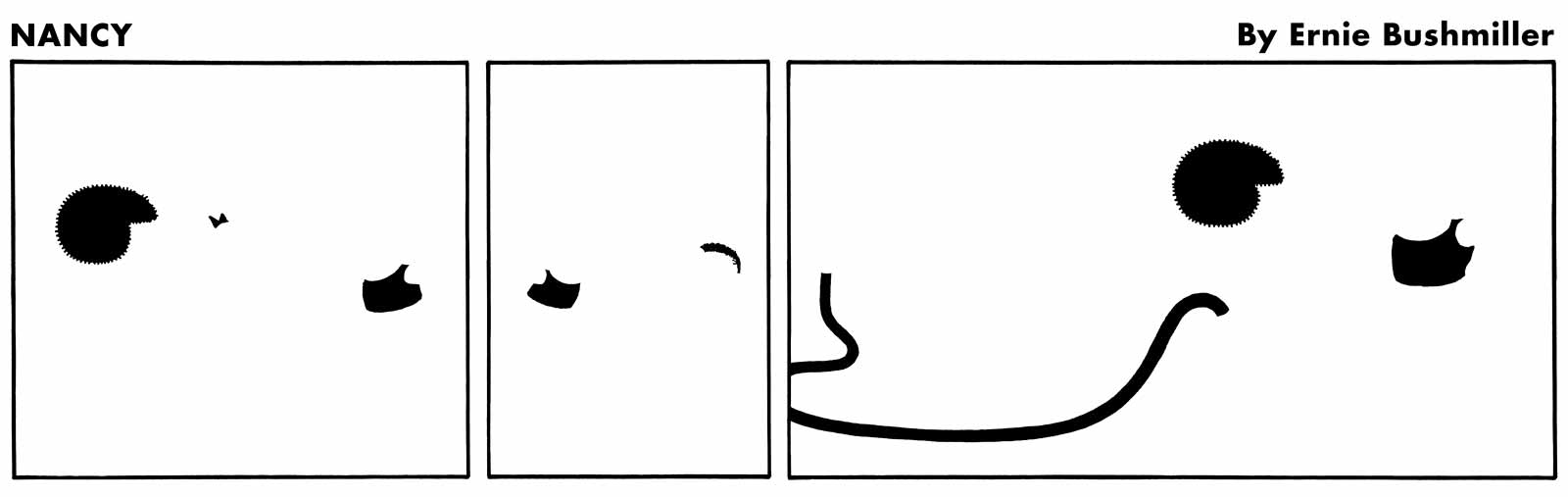

Nancy became a touchstone for artists to appropriate, distort, and transform. In Raw, Mark Newgarden’s 1986 comic Love’s Savage Fury depicted a Nancy whose minimal facial features rearrange while Bazooka Joe, a Topps bubblegum package mascot, eyes her across a NYC subway. Newgarden (who worked at Topps and co-created The Garbage Pail Kids) and Paul Karasik (a Raw associate editor and cartoonist who would go on to co-write the graphic-novel adaptation of Paul Auster’s City of Glass) then collaborated on a 1988 essay titled “How to Read Nancy” that deconstructed the elements of a single 1959 Nancy gag in nine ways across eight pages. By isolating elements of the comic, they explored how each piece supported the entire gag—for example, solely the dialogue of the strip; then solely the spotted blacks; then the arc of the horizon line, etc.

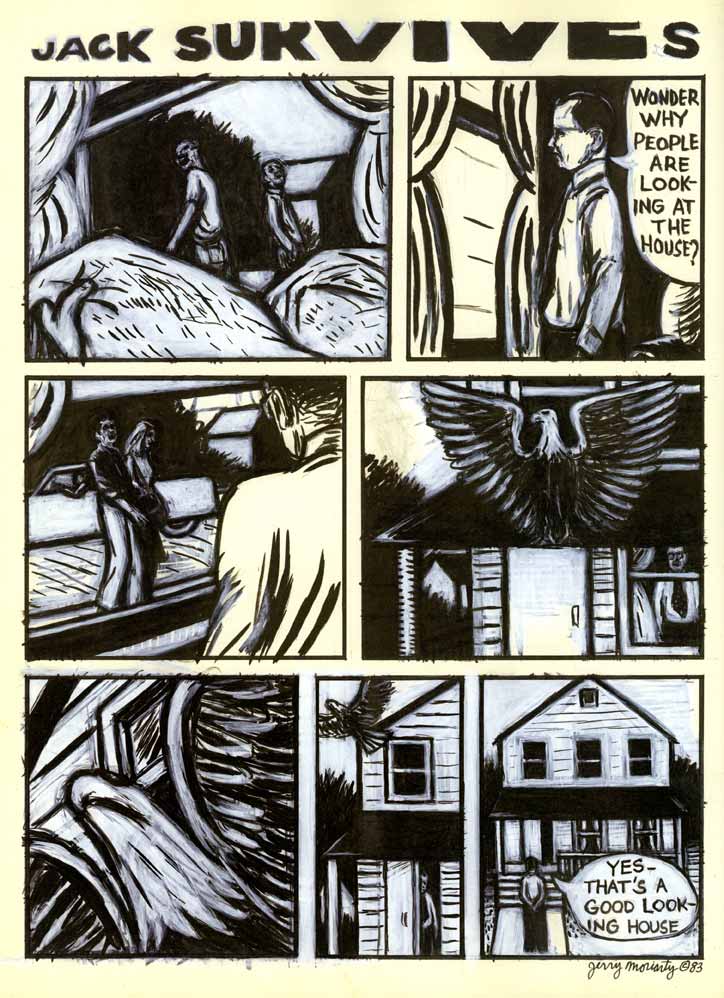

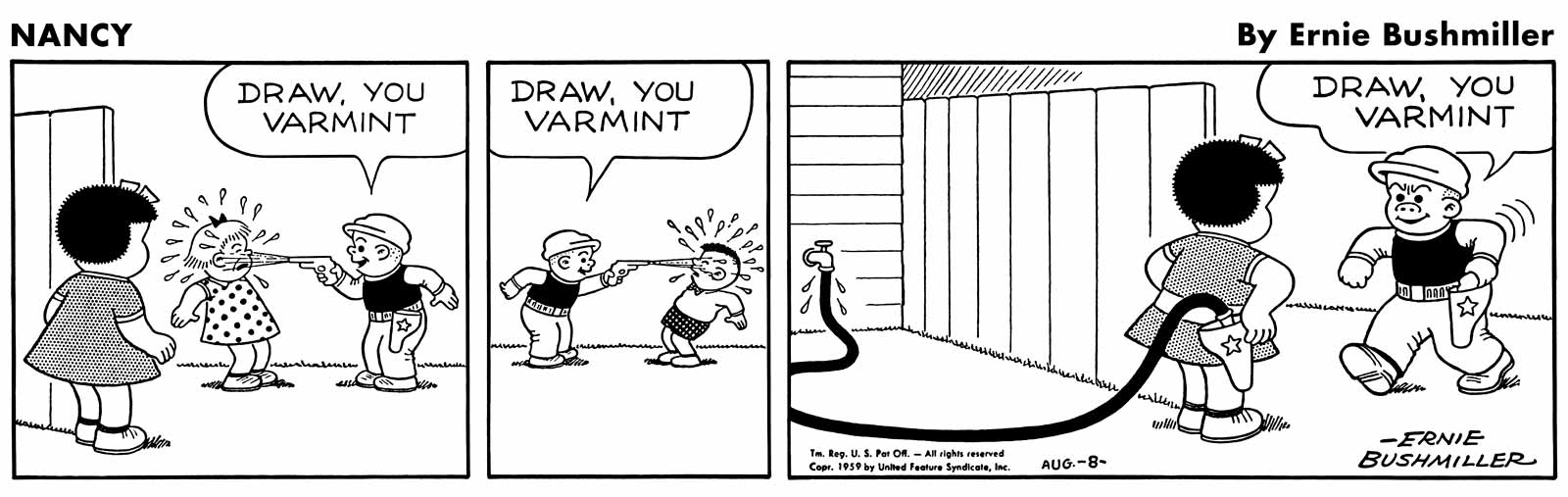

What Newgarden and Karasik’s essay did was explain how very deliberate every decision in Bushmiller’s composition of Nancy was. Every mark in this 1.5- by 5-inch space was in perfect concert with the whole. For example, the placement of blacks of Nancy’s hair and Sluggo’s shirt create a graphic band that transitions into the long hose line that swiftly directs our eyes to the culmination. Sluggo faces left, then right, then left again to create a visual counterpoint to his dialogue that creates a rhythm, again leading to the gag’s climax. Everything serves a single gag, and the mechanics to deliver that gag are clearly visible. These same mechanics of comics design and pacing can be seen in Chris Ware and Carol Tyler’s novelistic stories, or most strongly in Jerry Moriarty’s painterly, poetic comic shorts, collected in his books Jack Survives and Whatsa Paintoonist.

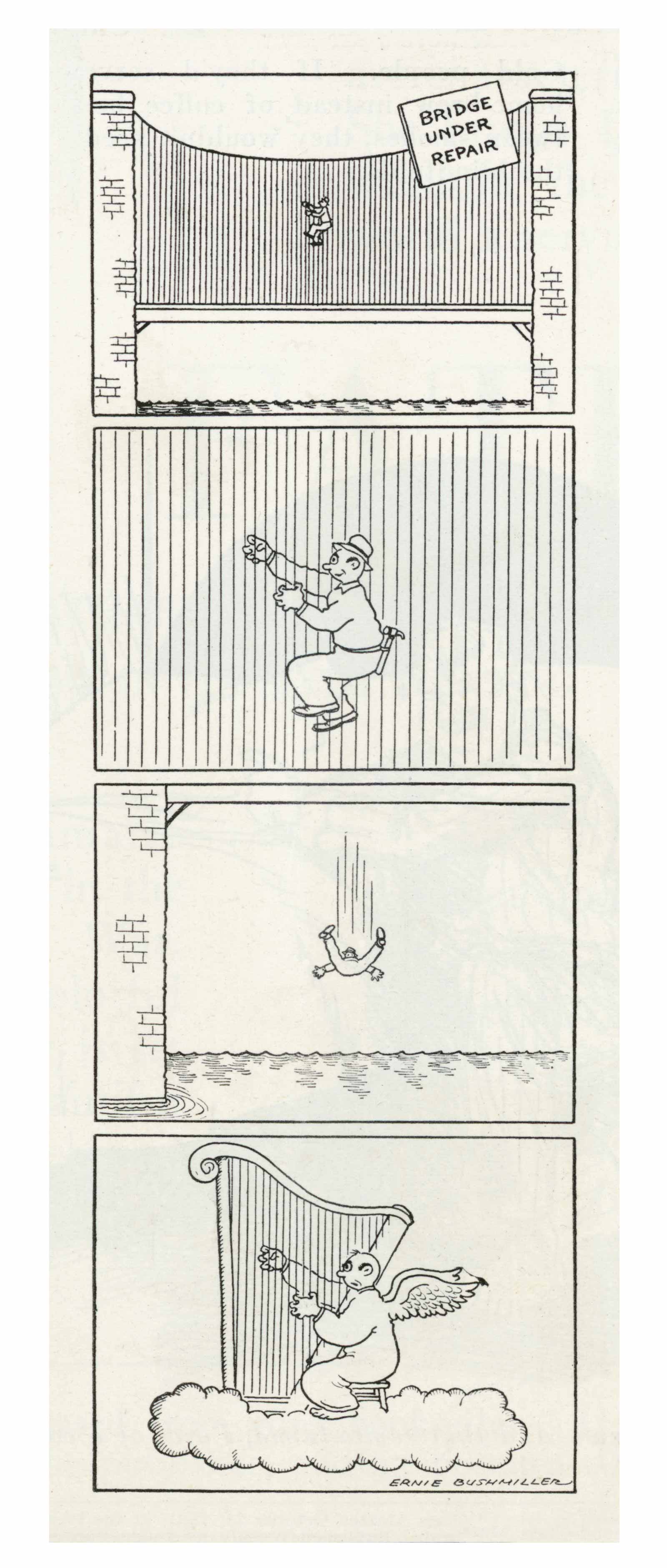

Three decades later, in an epic feat of comics fandom, research, and obsession, Newgarden and Karasik have expanded that essay into a 274-page book examining over forty elements of the same 1959 gag. This gag comic strip now joins the ranks of works of art that have entire books dedicated to them. What Newgarden and Karasik have done here is clearly, methodically, often hilariously explained the unique beauty and craft of comics. This book-length How to Read Nancy also includes a short biography of Bushmiller and a history of hose-themed gags at the end (providing examples of drawn gags that climax with erupting hoses dating back to the late 1800s). It also reprints some of Bushmiller’s early, pre-Nancy works, including this gem.

Advertisement

Today, comics are studied in colleges and reviewed in prominent magazines, but they are often discussed either as vessels for urgent, personal stories or as objects filled with beautiful, unusual graphics. They are rarely discussed or reviewed for their “cartooning,” the particular panel-to-panel magic, the arrangement of elements that mysteriously combines reading and looking, and distinguishes why a comic like Nancy is masterful and others are not. Beautiful cartooning affects a comic the way a well-chosen word, arriving at the right time in a sentence, makes for good writing, or the way a room composed with the right combination of things in the exact right places is good interior design.

For instance, one chapter of How to Read Nancy, titled “The Leaky Spigot,” focuses on the number of droplets placed around the spigot at the center of the strip. Four droplets communicate that there is a great deal of pressure pulsing through the hose. The greater the pressure, the more rewarding Nancy’s vengeance will be. Two or three droplets would not imply this strength of pressure. Five might suggest a malfunction, and would break the graphic symmetry of the design. Karasik and Newgarden also note that the droplets to the right are slightly smaller and therefore in spatial perspective. Every element of the strip is analyzed to this degree of fascinating and humorous detail.

By the time I read Nancy, in the 2000s, it was already a revered comic strip, published in hardcover collections. Admired alternative graphic novelists had long sung its praises. Nevertheless, Nancy is so unpretentious that its subtle genius always feels to new generations of readers like a fresh discovery. Nancy occupies a surreal, vague landscape of fences, sidewalks, and grass. Strips rarely address current issues or events, except for regular holidays like Valentine’s Day or Labor Day. Because the strip never addresses topical issues, its timelessness allows one to project onto it contemporary issues and symbols. Reading the 1959 strip in 2017, it was hard not to see a woman with an afro about to take down a penis-gun-squirting bully.

Nancy was also important to Scott McCloud, whose 1993 Understanding Comics remains the most popular comics-studies book. Understanding Comics has a big-hearted enthusiasm for the potential of the comics art form, and it inspired a generation of cartoonists to be more formally playful. McCloud devised his own Nancy card game and encouraged students to use the strip as a tool for further experimentation. Rather than take that approach, How to Read Nancy is closer to Hitchcock/Truffaut (1966), in which younger artists examine the work of a master. Just as Hitchcock’s techniques illuminate the medium of film to a degree most filmmakers do not, Bushmiller’s illuminate comics.

The beauty of cartooning may be difficult to appreciate, especially for those who have not been versed in cartooning for years. By dissecting this gag strip so systematically, How to Read Nancy is important for people working in the form, and also for the cartooning medium as a whole to be understood and recognized as the unique art form that it is.

How to Read Nancy, by Mark Newgarden and Paul Karasik, is published by Fantagraphics Books.