On the evening that I first walked out of Steve DiBenedetto’s new exhibition of paintings, “Toasted with Everything,” I looked up at the navy sky, down the asphalt street, and felt dizzy with euphoria. A later visit helped me articulate my pleasure: DiBenedetto had made sensual, profound, and profoundly imaginative paintings that are certain of their purpose but impossible to pin down. They are, as he told me later, like slot machines that never stop spinning. Watching the spinning numbers and symbols, which, in these paintings, are bodily masses and gracefully pulsating color applications, gave me a glorious buzz.

Steve DiBenedetto was born in 1958 in the Bronx and grew up in suburban New York, with frequent trips back to his home borough. He received a BFA from the Parsons School of Design and has lived in the city ever since. He first gained notice in the early 1990s with hallucinatory paintings filled with loaded symbols (some of them inspired by psychedelics theorist Terence McKenna’s notion of human transformation) such as octopuses, UFOs, helicopters, Ferris wheels, and glass skyscrapers, accompanied by virtuosic flights into amorphous color blurts and geometries. DiBenedetto was and is interested in events that occur on the other side of the window of consciousness.

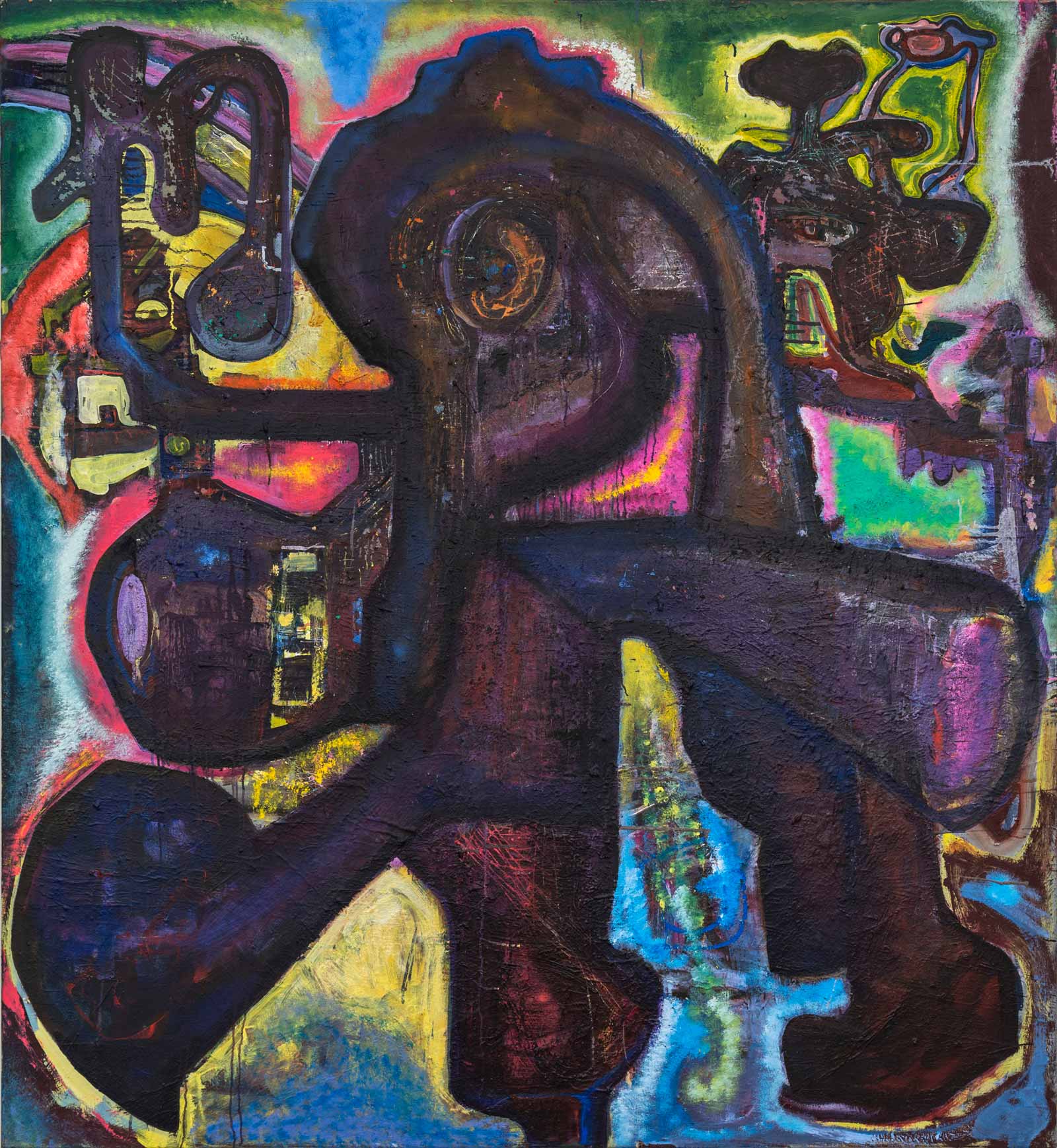

The current show is a distinct break from the tropes he has employed since the Nineties. In place of distinct symbols is a consistent use of vague, distressed humanoids as an armature for energetic inventions in paint and a renewed interest in unnameable emotional states (the artist warmed up for this current series by drawing images from his childhood copies of 1960s Famous Monsters of Filmland magazines). Metaphysical Salami (2018)—the humor of the titles betrays the artist’s own sometimes goofy sensibility; he is a serious painter, but not self-serious—resembles a Hans Hoffman grid merged with a dopey creature struggling with aubergine tubular extrusions.

None of this would be so effective if it wasn’t executed with DiBenedetto’s paint handling. In and around the wall-eyed mass are luminous flashes of light, from rosy pinks to aquamarine blues, like mini-Turner paintings amid the chaos. DiBenedetto excels at building up and scraping away at layers of oil paint in order to produce a rough-edged finish, but he is equally adept at the graceful sinuous strokes one might associate with Brice Marden, as well as fluffy puffs of pigment.

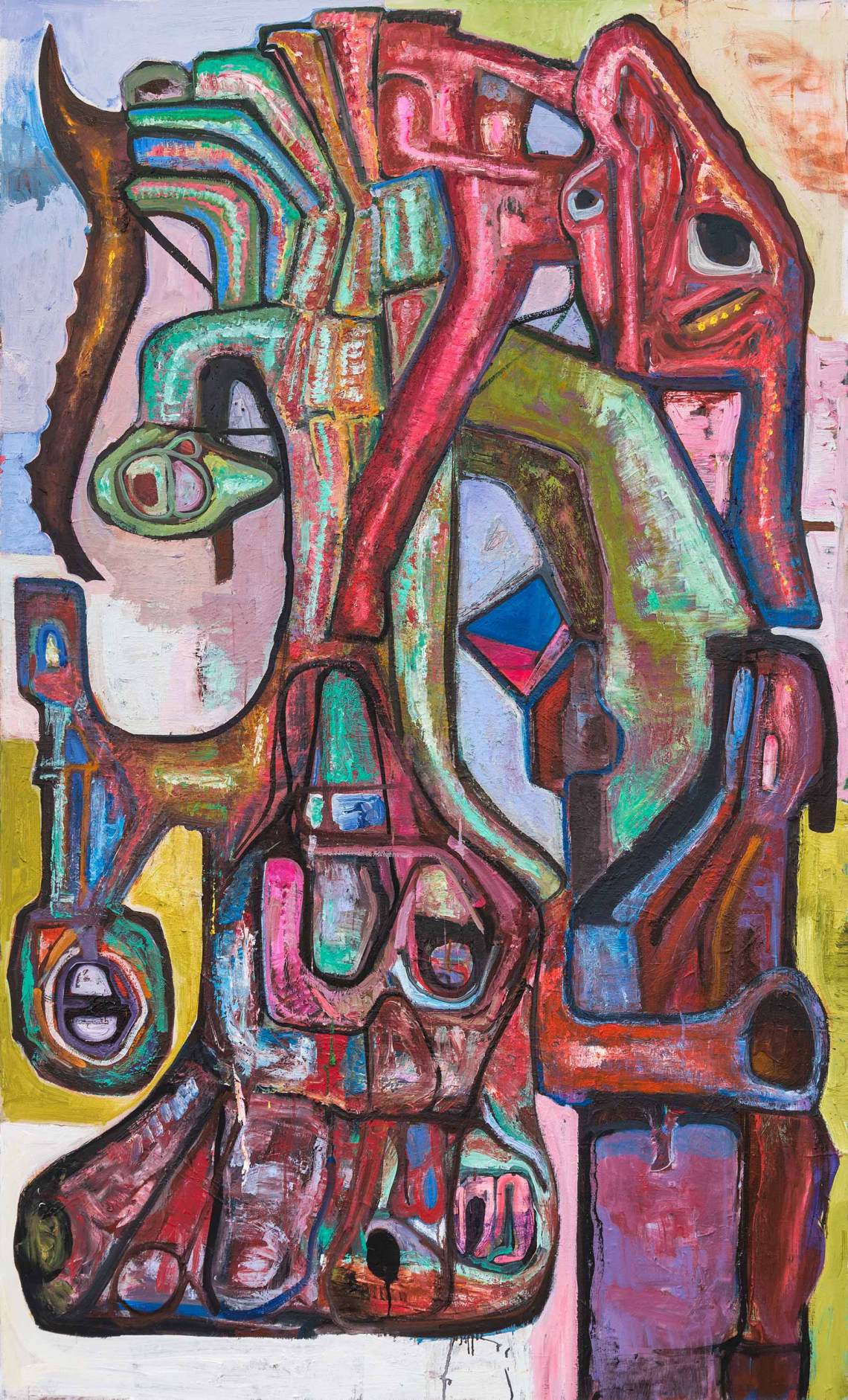

In Three Third Eyes (2018) he also employs a staple of mid-century abstract painting—the modernist grid—to stunning and colorful effect, acting as a support for what looks like an assemblage of ingeniously imagined spare organs and limbs. But in every hulking form lurk moments of grace: in the center of the painting, a sky-blue patch illuminates a blue, red, and pink crystalline diamond. A tentacle hangs off the thing, its pincer pointing to what resembles the barest intimation of a pietà, aglow in blue light. The grid here is a hopeful mélange of aquamarines, pinks, yellows, and whites. Pictorial grids are perhaps the through-line for the artist, but rather than instrumentalizing them as physical objects, in these paintings DiBenedetto deals with the grid purely as multifaceted color-blocking. If all representational references fail, there is always the grid.

And within that space, DiBenedetto wants us to envision our own clumsy humanity. A recent Artnet interview by Ben Davis of Hal Foster might suggest a way to think of DiBenedetto’s historical and philosophical roots. In discussing the idea of the “brut” in the work of Jean Dubuffet, Georges Bataille, Asger Jorn, Eduardo Paolozzi, and Claes Oldenburg, Foster identifies something that seems to echo DiBenedetto’s project: “For all the sense of the catastrophe of humanism, they work very much in the name of the human—it’s just a human that is very denatured…. They just want to make a humanism that’s adequate to relate to the destruction of the human.”

This kind of earnest, wide-awake, and self-aware humanism, very much of a pre-Seventies postmodern variety, is found in all of the paintings in the exhibition, and links DiBenedetto to his peers Huma Bhabha, Matthew Barney, and Carroll Dunham. In the titular painting, Toasted with Everything (2018), DiBenedetto achieves perhaps his finest large-scale work: tentative dabs combine with vicious scraping and loping thick curves to reveal creatures that would be at home with the Creature from the Black Lagoon and Frankenstein in Famous Monsters of Filmland, with shades of Jean Dubuffet and Peter Saul. But they are first and foremost creations of the physical act of brush and scraper on canvas—where once DiBenedetto layered his paintings with allusions to psychedelic phenomena, science fiction films and literature, and modernist architecture and machinery, now he is constructing his own, without any external references. They sometimes look as though he’s coaxed slabs of meat together, Francis Bacon-like, with smooth chunks of granite. And then, sometimes, they are all sweeping strokes of color.

Advertisement

DiBenedetto encodes his works with ideas about paint as if to answer the question, What should a painting look like, in all its confusing, diffuse, and oddball glory, in order to make us feel that we’re human and engaged? Three-dimensional spaces built of curved planes; a Christmas tree held aloft by a tentacle in a wash of violet and emerald space; a luscious flicker of green off a fully-petalled flower; a cobalt blue biomorphic form engorged with a yellow calligraphic swirl. I counted seven different eyes staring out of Toasted with Everything; they were not blinking.

“Toasted with Everything” is on view at the Derek Eller Gallery through April 22.