The beautiful queen gazed implacably at the man who stood before her, who had confronted her with a truth he hoped would make her squirm. “Knowledge is power,” he said, with a cocky smile. Calmly, the queen turned toward the guards ranked around them. “Seize him,” she said. “Cut his throat.” As the guards rushed to obey, a knife already at the upstart’s neck, she called out, “Stop. Oh, wait,” then laughed lightly, “I’ve changed my mind. Let him go.” As the guards withdrew, she approached her flinching challenger and said with chilling certainty: “Power is power.”

Stopping this video, I turned to the eighteen undergraduate journalism students at The New School in New York who sat with me around a square of melamine tables. It was the first two minutes of the first class I’d ever taught: “Facts/Alternative Facts: Media in America from Tocqueville to Trump.” For the rest of the semester, as we tackled works by Thomas Jefferson and John Stuart Mill, George Orwell and Hannah Arendt, Joe McGinniss and Michael Wolff, we would discuss palace intrigue at the White House, attacks on the press, and international warfare—albeit of the cyber variety, not the kind with swords and dragons. I had hoped Game of Thrones would make a congenial entry point to our subject for millennials who did not necessarily have a deep grounding in the history of the twentieth-century—much less the nineteenth-century (de Tocqueville’s age) or eighteenth, the era of our nation’s founding—but who understood the drama of archetypal battles.

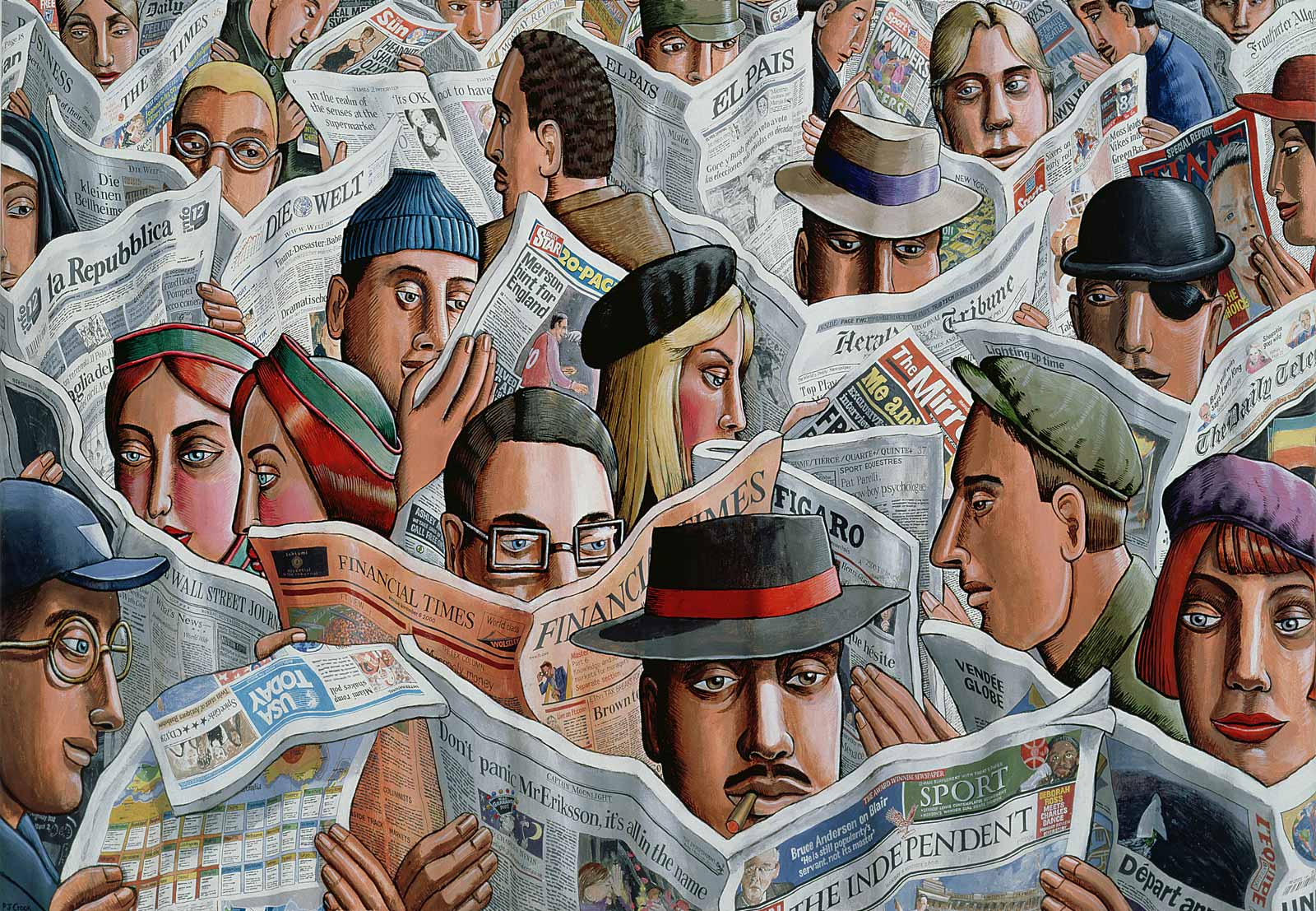

“What do we have in America that they don’t have in Westeros, that could make Lord Baelish’s words true, and wipe the smile off Cersei’s face?” I asked. They looked at me, mute and expectant (it was the first day, after all), so I gave them the answer. “We have newspapers,” I said. “We have journalists, who can publish the truth without fear of having their heads cut off. But before we can publish the truth, we have to define it, and we have to defend it.”

Pulling from my knapsack some relics of my decades as a journalist —“source,” we call it—massive review books, densely annotated; old fact-checking galleys, underlined in red; reporter’s notebooks and tapes; and dog-eared copies of texts I hold sacred, from Democritus to Sir Francis Bacon, from Alexis de Tocqueville to Friedrich Nietzsche. “These are our tools,” I told them. “This is how we prove what we believe to be true; by keeping concrete records of our knowledge.” Then, dividing the students into five teams, I gave each team a page from Nietzsche’s short essay on the wriggliness of words, “On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense,” and had them shrink their page down to 140 characters. In fifteen minutes, the students read out their condensed versions (in sequence), and laughed aloud, exulting in their ability to pare away the ornate language to reveal the gist. I called this exercise “Tweeting Nietzsche.” It would be our touchstone throughout the term, a reminder that to speak of facts is to speak of language—Nietzsche’s “mobile army of metaphor, metonym, and anthropomorphism”—and that journalists who intend to write factually in today’s hostile climate for news media must learn how to deploy that mobile army effectively. I wish I’d had a trumpet to sound the charge.

Before I became a full-time writer, my day job was defending the integrity of facts. For fourteen years, I was a fact-checker at The New Yorker magazine. Because I spoke French and—not well, but well enough—German, Russian, and Italian, I ended up with what you might call the “Hannah Arendt beat.” When the magazine published an article connected to totalitarianism, the Holocaust, World War II, the fall of the Berlin Wall, or the collapse of the Soviet Union, chances were I checked it—phoning the men and women who figured in the stories and re-interviewing them to clear up possible errors; reading mountains of documents, old and new; going to the library to get books; hunting for discrepancies. Google did not exist when I started fact-checking, thirty years ago, in June 1988. Checkers relied on paper sources, audiotapes, videos, and live interviews, in person or on the phone.

And that is why, on January 22, 2017, two days into Donald Trump’s presidency, when I heard Kellyanne Conway, counselor to the president, coin the phrase “alternative facts” on Meet the Press to justify White House lies about the size of Trump’s inauguration crowd, every cell in my body shrilled. It was as if a siren had gone off. Facts have been actual, not notional, for around five hundred years: the word “fact” as a statement or piece of information that can be proved or disproved entered the Oxford English Dictionary in the late sixteenth century, after Bacon (not Lord Baelish) had declared that knowledge itself was power—ipsa scientia potestas est. Watching Chuck Todd’s jaw drop as Conway denied the very existence of facts, I thought back to a piece by Timothy Ryback I’d checked for The New Yorker in 1992. Titled “Report from Dachau,” it told the story of a German man, Nikolaus Lehner, who’d been a prisoner at the Dachau concentration camp in the Nazi era, and had chosen to stay in the town of Dachau after the camp was liberated in April 1945.

Advertisement

When you’re a fact-checker, you’re supposed to read each article thoroughly before you call its subjects, to be sure you’ve absorbed the story’s arc—and identified its potential factual booby-traps—before you dig in. (The longtime head of The New Yorker’s checking department, Peter Canby, came in to give my students a factual master class.) But time was short, and the article was long, so I called Lehner before reading the piece in galleys, talking it through with him, point by point, almost by rote, until, thirty-nine pages in, as the narrative looped back to Lehner’s past, I began to cry, mid-sentence. I discovered that the man to whom I’d been speaking for two hours was not the person I thought he was; not a German at all, but a Romanian Jew.

He’d been rounded up in Budapest, Hungary, in December 1944, and put in a cattle car of prisoners headed for Dachau. Minutes before the train arrived, a young German officer came up to him, confided that a non-Jewish prisoner had just died, and instructed him to take the dead man’s name. That name was “Nikolaus Lehner.” When the guards called, “Jews step out!” the prisoner kept still, at the young officer’s insistence. From that moment, he assumed a “new existence,” and he kept that new name. He stayed in Dachau after the war, he told Ryback, because he hoped to build “an understanding between peoples.” For a decade, he had been embroiled in a struggle (the main subject of the article) to create a Haus der Begegnung in Dachau, a “house of encounter,” where young people with no memory of the atrocities of the past could “commemorate and learn.”

A classroom, it seemed to me, was a readymade “house of encounter.” Could I create a class that would teach the next generation of journalists how to confront history and “alternative facts” head-on? Hearing Conway pronounce that Orwellian phrase, I thought of Hitler’s and Stalin’s abuses of fact and reason, and of the murder of human beings that historically attends the murder of truth. When, the next month, Trump called the media the “Enemy of the American People,” echoing Stalin’s vrag naroda (“enemy of the people,” a term dating back to the tyrannical Roman emperor Nero), I proposed my course to The New School. I called it a boot camp in corrective democracy.

I taught “Facts/Alternative Facts” last fall, I taught it this spring, I’m teaching it next fall, and I’ll teach it as long as students keep enrolling. I update the curriculum weekly, weaving in the latest news, so that the students can see the line that connects the past to today. It can sometimes be challenging for them to face the uncertainties of the present. During a heated discussion after the Parkland school shooting about the conspiracy theories that erupt whenever anyone challenges Second Amendment rights, one student blurted out, “I hate politics! It’s so depressing!” I paused our debate, and we all took a breath.

“Politics is people,” I told her. “Politics is the story of citizens, and how they get along with each other over time. It’s not fixed; it changes. Good cycles follow bad ones, and vice-versa; and journalists can bring on good cycles with their reporting.” To cheer her further, I asked the class to name positive changes the press had helped bring about. “Women getting the vote?” said one. “The Civil Rights Act?” said another. “Impeaching Nixon?” suggested another. Nixon resigned, actually, but yes, under the threat of likely impeachment. (Two weeks later, we would watch Robert Redford’s documentary All the President’s Men Revisited, which lately feels like a prequel.) “Gay marriage?” said another. “You see,” I responded, “Politics is a game people play to test their power. As journalists, you can help make the game fairer.” The demoralized student took heart. Her midterm paper was one of the best in class: she compared the Trump White House to the reality TV series Survivor, effectively and with humor.

Advertisement

Early on, I ask the students to share their first political memories, to remind them of their own part in this civic endeavor. One student this term recalled being hoisted up to sit on a tank in a military parade in his native country when he was three; another, last term, spoke of the time her immigrant mother cried when her relatives weren’t permitted to come to America; yet another remembered voting in a kindergarten election for George W. Bush, not John Kerry, for president in 2004, because all the other kids did, only to discover upon returning home that his parents and all their friends were Kerry supporters. That was when he understood, he said, that politics is “tribal.”

My first political memory, I tell them, was when I was six, watching the Watergate hearings on TV with my parents. Nixon might be “impeached,” the anchor said. Having just read Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach, I thought Nixon would be shut up in a giant peach pit like James, alongside monstrous insects. The next year, when Nixon resigned, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, the journalists who had rooted out the truths behind Nixon’s smokescreen of lies—his “mobile army of metaphors”—became my heroes. It was because of them that I believed that journalism was a noble profession, and because of them that I believed, and still believe, that knowledge is power, when it is defended with the armament of fact. It is up to those who make it their job to protect the record of truth to show others who declare that might is right, and power is power, that history will prove them wrong.