Haiti, good historians agree, is where the Enlightenment came home to roost. France may have been where Rousseau penned The Rights of Man, but it was in France’s most brutal and lucrative plantation colony—the Caribbean sugar island of Saint-Domingue—that a half million enslaved Africans rose up in 1791 to kill their masters and ask the West: How universal, really, is your idea of universal rights?

Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti) was transformed, by Toussaint L’Ouverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, into a free black nation that France saddled with unpayable debts and whose sovereignty the United States didn’t recognize for decades. But the celebrated “Black Jacobin” revolutionaries were not the whole story of how Haiti came to be. Rousseau’s ideas were not the only influences to shape a society built from the ashes of its old plantations. And among the more mysterious facets of Enlightenment culture to leave their mark here was the secret society that the British artist and documentarian Leah Gordon explores, with several collaborators, in a marvelous exhibition about Haiti’s Masonic tradition, “Vernacular Universalism: Freemasonry in Haiti and Beyond,” now at the Clemente Center on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

Leah Gordon has spent over twenty-five years documenting Haiti’s cultural riches—her photographs of the famous carnival in the southern city of Jacmel are touchstones. Gordon is also a co-founder of the Ghetto Biennale, a gathering of Haitian and international artists that since 2009 has centered around the outdoor studio and atelier of the prolific sculptor André Eugène, just off the bustling Grand-Rue in downtown Port-au-Prince. Eugène’s distinctive work—made with engine manifolds and hubcaps and skulls, and often invoking vodou’s lords of the cemetery, Gede—fills his yard, and provides the guiding aesthetic for Atis Rezistans (“Resistance Artists”), a collective of artists from nearby streets. Several members of Atis Rezistans also earn money painting portraits of soccer stars or Rihanna onto tap-tap communal taxis or cinderblock barber shops, and a few of their pieces accompany Gordon’s photographs at the Clemente Center, whose galleries occupy what were once the airy classrooms of Public School 160.

Freemasonry in North America today is mostly associated either with accountants and dentists enjoined to participate in obscure rites in the suburbs, or with historical conspiracy theories parroted by readers of Umberto Eco, viewers of Infowars, and others who love to rehearse how many US presidents have been Masons. But with its roots in the guilds of medieval tradesmen who built that epoch’s castles and walls (and whose tools remain central in Masonic iconography), Freemasonry furnished a social space, in lodges on both sides of the Atlantic in the eighteenth century, for men to question the authority of aristocrats and the church.

In colonial Saint-Domingue—where Freemasonry arrived with French merchants and soldiers—it became one of the few European institutions that admitted black members. The New World’s chaotic and cosmopolitan ports, in general, proved fertile ground for an order devoted not merely to helping unmoored men build fraternal ties helpful to business, but to mining the deep human past—our esoteric heritage of runes and pyramids and signs—to divine a universal knowledge. Elsewhere in the Americas, racism kept blacks from joining lodges or embarking on the series of initiations, or “degrees,” around which Masonic rites revolve. (One result was the Prince Hall Lodges to which many African Americans and West Indians still belong today.) But in French Saint-Domingue, Masonic ideas held great interest for the colony’s freedmen of color—the forerunners of Haiti’s political elite—and Freemasonry also seems to have overlapped, in untraceable but fascinating ways, with warrior societies brought here by slaves from Kongo and Dahomey, who won their freedom by force.

The leaders of Haiti’s Revolution were familiar with “the Craft”—Dessalines had his sword and scabbard engraved with a square and compass. Haiti’s very name—which its black founders borrowed from an indigenous Taino word for their “land of high mountains”—may even reflect a Masonic interest in Native American languages and lore. Vodou, a system of belief and rituals born from varied African roots by people who needed a shared way to articulate their common ties to Guinée and to one another, has long incorporated Masonic elements. In Haiti today, Freemasonry continues to thrive among the paragons of middle-class respectability—Haiti’s own accountants and dentists—who are less often documented than Haiti’s poor. And Masonic imagery and language, far beyond these Masons’ lodges, still pervades visual culture in a country where most signage is still made by humans.

Advertisement

This hand-hewn quality is evinced in this show in a wooden coffin-cover on which Michel Lafleur, whose paintings of famous fades adorn barber shops across Port-au-Prince, has affixed a red and gold skull and masons’ squares. Coffins are key to the third degree of Masonic initiation, and one also features in André Eugène’s contribution, a typically spooky piece involving a doll’s head and scrap metal. Eugène and Lafleur’s associate Molej Zamour, a woodworker, has fabricated three Masonic columns modeled on a similar trio from the eighteenth century that Lafleur has painted with three principles—“Foi” (faith), “Espérance” (hope), and “Charité” (charity)—and their associated Masonic symbols. It’s hard to go far in Haiti today without seeing one of these words painted on a storage depot or tap-tap.

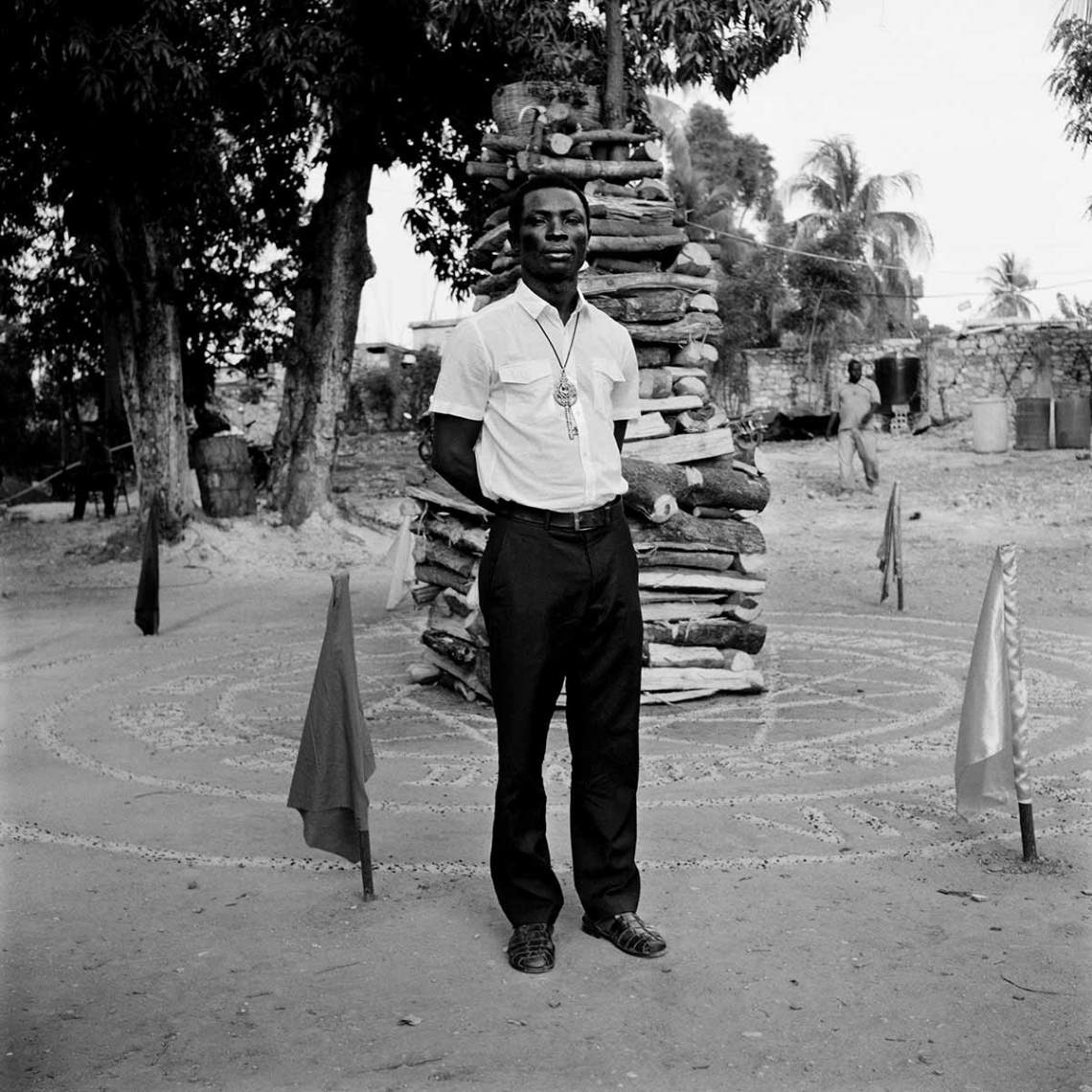

“Vernacular Universalism” also includes a pair of sequined flags by the vodou flag artist Yves Delva—they hail Ti Jean Petwo (as John the Baptist, the patron saint of Freemasons, is known to vodouisants)—and a wall of “Solomonic pentacle drawings” by Ernest Dominique, an artist and writer who has been initiated to the thirtieth degree as a Mason. But the show’s core comprises twenty of Gordon’s photographs of Freemasons and their gathering spaces that took years of trust-building to enter.

Grouping these images into four assemblages of five, Gordon has arranged each set of pictures in the shape of a cross—a form as resonant to Freemasons and in the cosmologies of vodou as it is to orthodox Christians. Black-and-white and color images, saturated with the reds and blues of Haiti’s national flag, are juxtaposed, creating intriguing visual dialogues and rhymes. Illuminating a world usually hidden from outsiders, these images, as the scholar Katherine Smith observes in a text accompanying them here, reveal “unexpected couplings: mysticism and civil society; secrecy and spectacle; solemnity and celebration; patriarchy and grace.”

Long before our current ignoramus-in-chief dubbed their country a “shithole,” Haitians had become used to Haiti being viewed as a place outside the West. But as these images remind us, Haiti’s past—its glorious revolution and its history of impoverishment alike—is inextricable from our own. This is a place, like the United States, where the fruits and failings of Enlightenment thought are everywhere you look.

“Vernacular Universalism: Freemasonry in Haiti and Beyond” is at the Clemente Center in New York City through June 23.