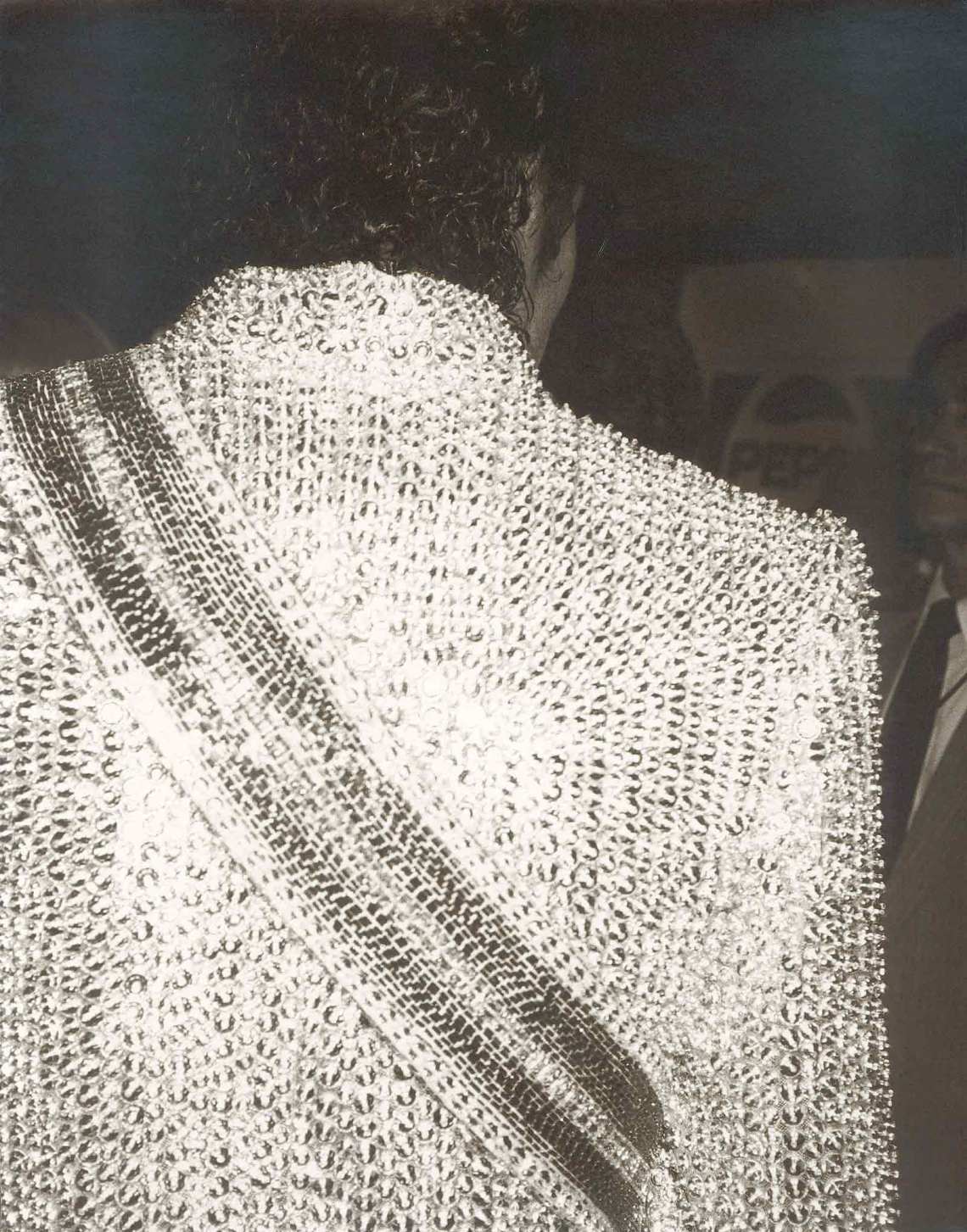

At first, the artist Kehinde Wiley didn’t believe it was Michael Jackson calling so he didn’t pick up. “Will you please answer the fucking phone?” a mutual friend said. And sure enough, not long afterward, a meeting was set up and Wiley and Jackson were chewing the fat on such things as the function of clothes as body armor and the distinctions between Peter Paul Rubens’s earlier and later brushwork. The resulting painting, completed after Jackson’s death in 2009, shows a magnificent Michael in full armor on an ivory horse, flanked by multicultural cherubim and vivid roses in a distant barren land, rainclouds overhead; the look on his face is hard, determined, haughty, with a hint of vulnerability underneath.

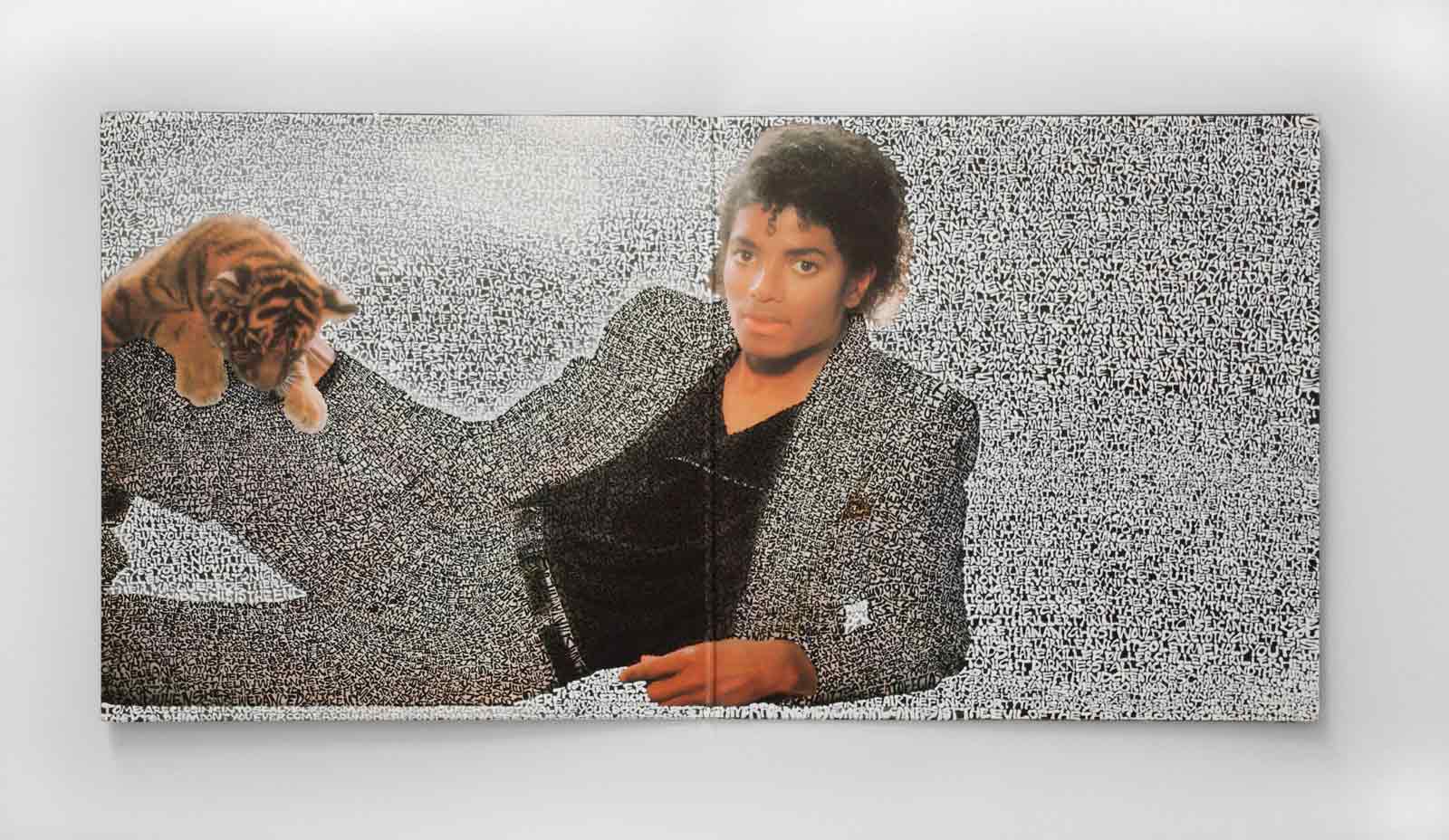

It was Michael Jackson’s astronomical celebrity that made Wiley think the call was a prank—a fame that is central to the National Portrait Gallery’s current exhibition of contemporary art inspired by Jackson’s image and work. Titled with a pun after, arguably, his best album (though some say Thriller, others Bad), “Michael Jackson: On The Wall” gathers together the work of forty-eight disparate artists exploring the legacy of perhaps the most frequently depicted cultural figure in history, and his fame is their common palette. He is inseparable from it. It was his making and his tragedy. It glows with a bright, mournful edge from every one of these works, probing the question of what might have been if his enormous success had not in some way required, or at least contributed to, his eventual annihilation.

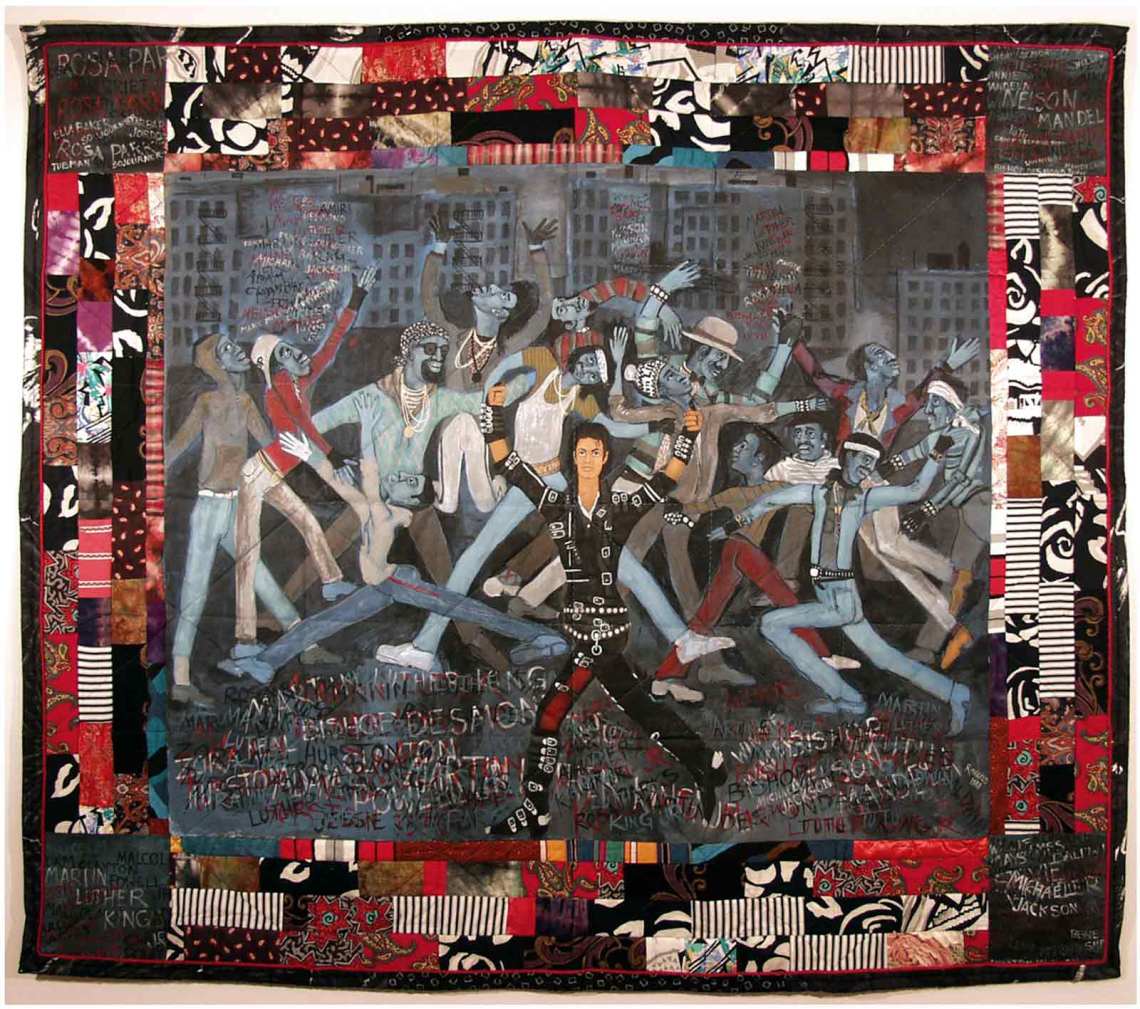

Wiley’s sumptuous portrait, displayed here for the first time in the UK, is mounted against a recurring blood-red background, adjacent to a contrasting work by Lyle Ashton Harris, Black Ebony II (2010), a painting on Ghanaian funerary fabric of Jackson on the cover of Ebony magazine in 2007. While Harris’s approach examines the confluence of modern globalization and African cultural tradition amidst the hauntings of colonial tyranny, Wiley’s work is known for presenting contemporary black figures (Barack Obama among them) in the visual language of European art history, thereby disrupting stereotypical perceptions of black identity and representation. There is a sense, in both portraits, of Michael Jackson as a site of supreme existential determinism, imprisoned by his image, its politics, it metamorphosis, its discomfort, yet uncompromising in his idiosyncrasy.

Certainly during my childhood, I was aware that there was no one else quite like Michael Jackson. I liked his leathers and his strut, his riveting shrieks and his white suit in the Smooth Criminal video. Most of all it was the deep soulfulness in his music, it was a sound that seemed to unify all others. Then, of course, no one else could move like him, with that almost superhuman, logic-defying agility. He was a captivating demonstration of how the body can best make use of music, and one of the pleasures of this show is its natural sonic dimension. At the entrance is Donald Urquhart’s A Michael Jackson Alphabet (2017), recalling the Jackson 5 song, “ABC,” a vast, jumping display of buzzwords, “D is for Dance!,” “T is for Thriller,” going all the way to “Z is for Zombies.” Then there is the music itself, wafting out from the blood-red rooms, that unmistakable, honey-toned voice and a Quincy Jones backing track. You walk into a windswept dance move, a digital vision in four parts of Michael in motion, comprised of stills from his 1987 short film The Way You Make Me Feel, rendered here under the same title by the installation artist Dara Birnbaum. In one still image, Jackson’s sharp little chin and nose point upwards into blue mist; in another, the boyish hips are jutted, the hands arranged above the head like a bird in flight, beautifully capturing the ethereal lightness of his movements.

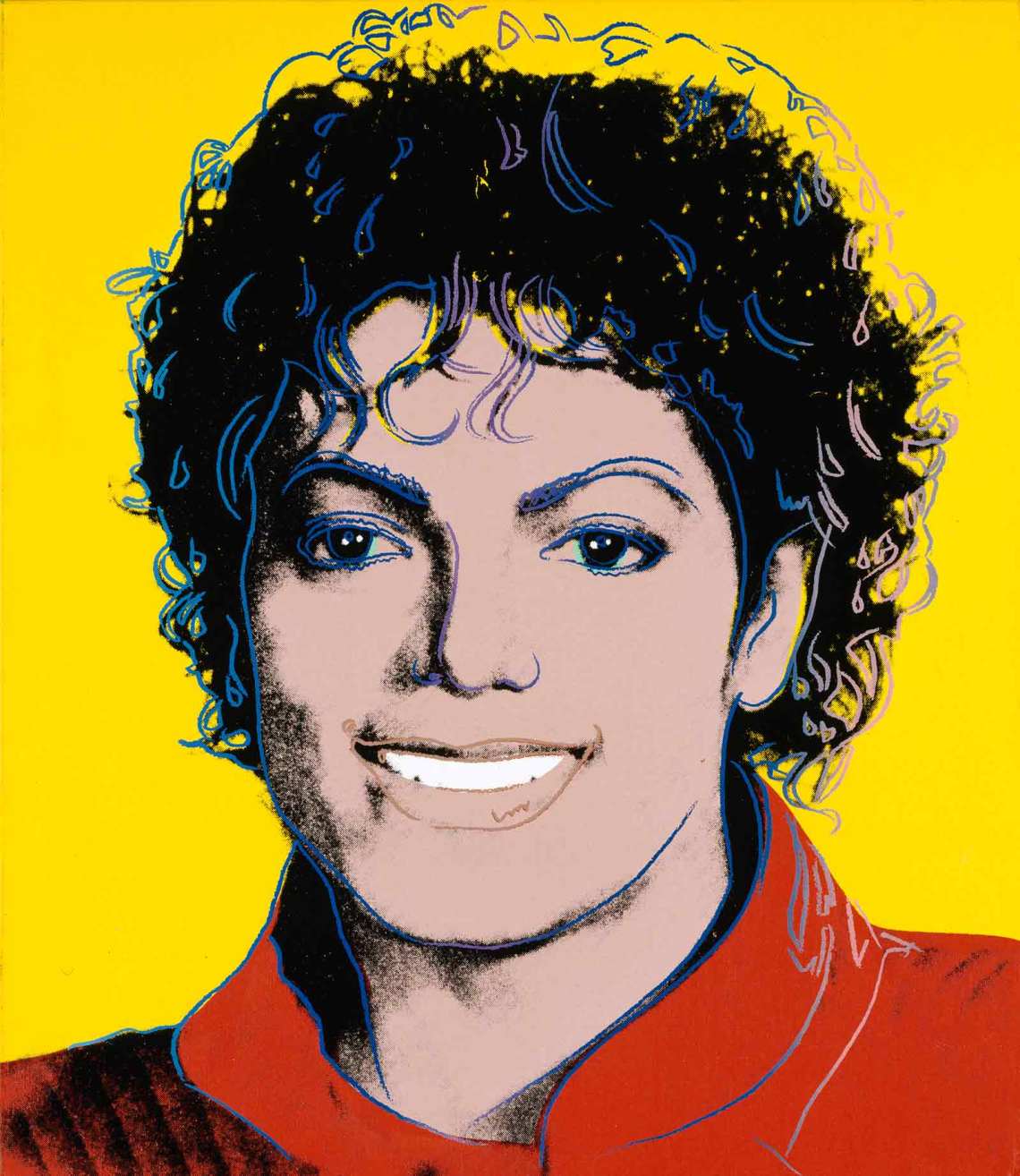

There are so many Michaels here, abstract and explicit, symbolic and personal, among the most striking the majestic, biblically-themed photographic portraits of David LaChapelle, thick with drama and fantastic weirdness. LaChapelle began his career working for Andy Warhol (whose 1984 blue-flecked rendition also appears in this show), and his large-scale series “American Jesus” depicts Jackson as a kind of funky, modern-day saint, shrouded in religious iconography and a rich, slightly saccharine naturalism. In The Beatification: I’ll Never Let You Part For You’re Always In My Heart (2009), Michael is gaunt and ghostly, his stage clothes loose around his frame and unspectacular next to the lush-veiled angel by his side, her holy hand resting lightly in his, a navy ocean at their backs. It has a feel of the world having ended, with Michael perhaps the only one saved, after a lifetime of crucifixion. In American Jesus: Hold Me, Carry Me Boldly (2009), the picture is less hopeful, less redemptive, with Michael splayed dead in the arms of a possible, heavenward-looking Jesus.

Advertisement

In almost every portrait, Jackson’s eyes are striking—staring, testing, or withholding—and a section of the exhibition is dedicated to them. They are headboard-studded in Isaac Lythgoe’s surreal The Only Here Is Where I Am (2016), just the eyes, defaced and disembodied, yet recognizable. In Gary Hume’s characteristically spare and graphic high-gloss painting, simply titled Michael (2001), their clear sadness is highlighted by chunky black brows and the frightened red lips, that deathly white complexion, drawn from the classic image of the man at perhaps his most vulnerable. Meanwhile, there is footage playing in a dark annex of the Bucharest leg of Jackson’s 1992 Dangerous tour, shortly after the fall of communism and the collapse of the Eastern bloc. Crazed fans scream at a turn of his head, a flick of his hand. Even a suggestion of the removal of his sunglasses causes fainting and fits of crying. The masks that were handed out for free at this concert are arranged in an eye-level row surrounding, also watching the screen, their empty pupils replaced by electric lights. The recurring theme throughout is of Michael Jackson as a godlike figure, existent among us though infused with the divine, visible yet unreachable, with the music the cord that connected him to us.

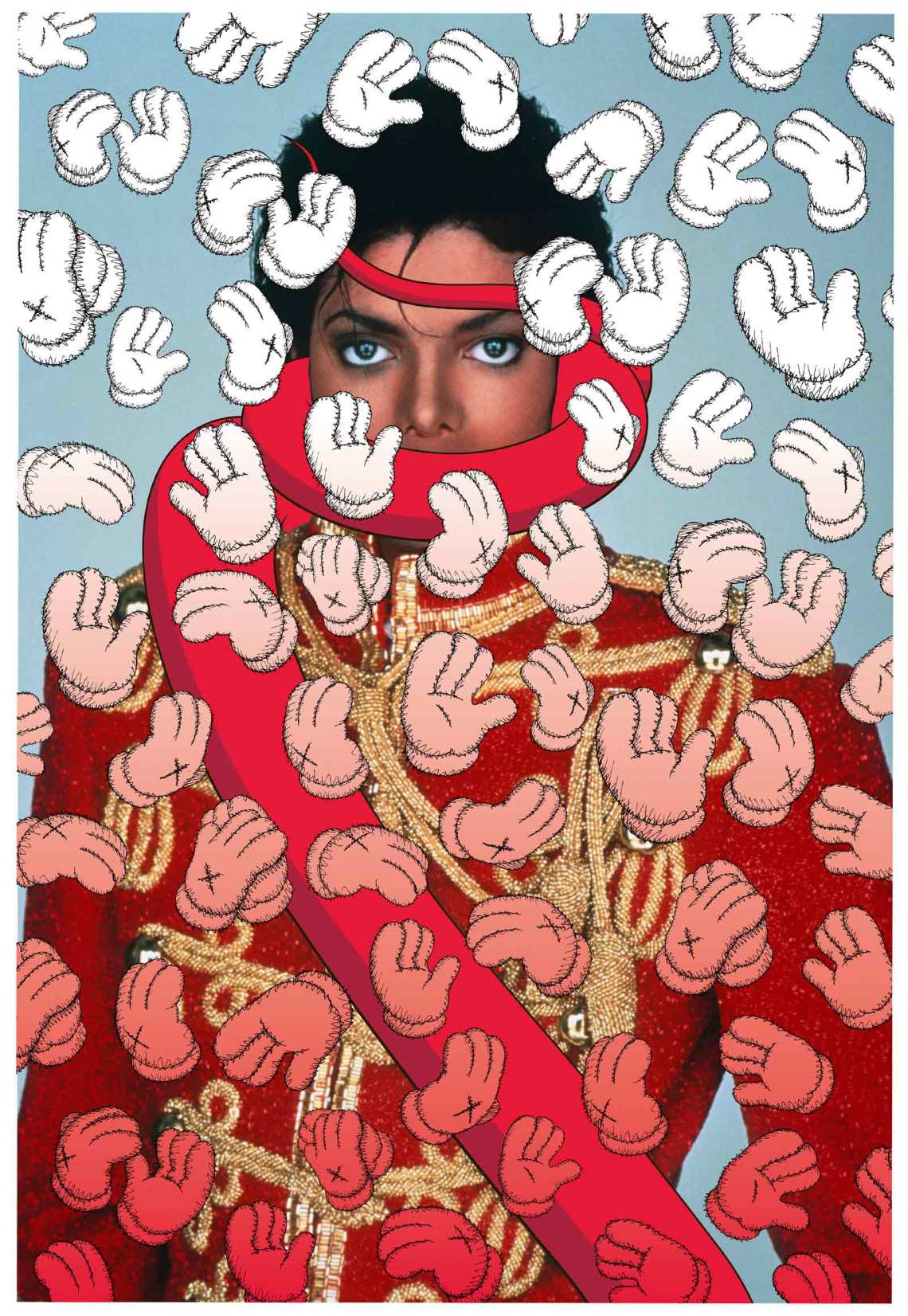

The show would not be complete without Bubbles, for a time the world’s most famous chimp, or Jackson’s close friend Elizabeth Taylor, or that leather dinner jacket with the cutlery hanging off it that used to make people laugh, all of which are present in various guises. But the more interesting work is that which illuminates Michael Jackson not as eccentric celebrity, but as a human being with specific cultural significance globally, such as Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s collages of a Nigerian home (As We See You: Dreams of Jand, 2017), and Todd Gray’s seductive yet elusive layered photographs that replace Michael’s head with another image, resisting binary interpretation. Jackson signifies many things, a pair of dancing shoes and a bouquet of balloons, a cluster of microphones, as in David Hammons’s Which Mike do you want to be like…? (2001), yet his essence remains as mysterious and private as our deepest selves. He was an expression of blackness and of sheer individuality at the same time.

This is what the last piece in the exhibition seems to point to, Candice Breitz’s video montage King (A Portrait of Michael Jackson) (2005), from which Jackson himself is absent, yet conjured in the bodies of several on-screen German fans singing their way through Thriller. They are each singing the same songs yet every song is made different, multiple, by the person singing it; that quiet one there who is hardly moving, the flirty belly-dancing one, the cocksure lookalike one, the middle-aged geeky one. They are all passionate, knowingly on show, but imbued with self-possession, the music a common language. A parting evocation, perhaps, of what the artists themselves saw and found in Michael Jackson.

“Michael Jackson: On the Wall” is at London’s National Portrait Gallery through October 21.