It may seem strange to include the subject of three modern biographies in a column called “Forgotten Feminisms.” But mention the name “Ernestine Rose” to the next feminist you meet, and odds are she’ll have no idea who you’re talking about. Rose has little or no name recognition outside defenders in university Gender Studies departments.

That’s a big gap in our collective memory. Rose began agitating for women’s rights a decade before Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and she mentored them both. As a public speaker, Rose was more famous—and notorious—than they were, at least in her heyday. Rose “has as great a power to chain an audience as any of our best male speakers,” said the Albany Transcript in 1854, meaning the comparison as a compliment. “A good delivery, a forcible voice, the most uncommon good sense, a delightful terseness of style, and a rare talent for humor,” an anonymous female journalist wrote in 1860. Rose also had the unfair advantage of good looks: a French journalist and reformer once described her as “a slender petite, gracious woman, with a beautiful forehead, sparkling eyes of an extraordinary sweetness, even, white teeth, and a charming half smile.” The newspapers called Rose “The Queen of the Platform” in an era when lectures rivaled theater as a form of popular entertainment.

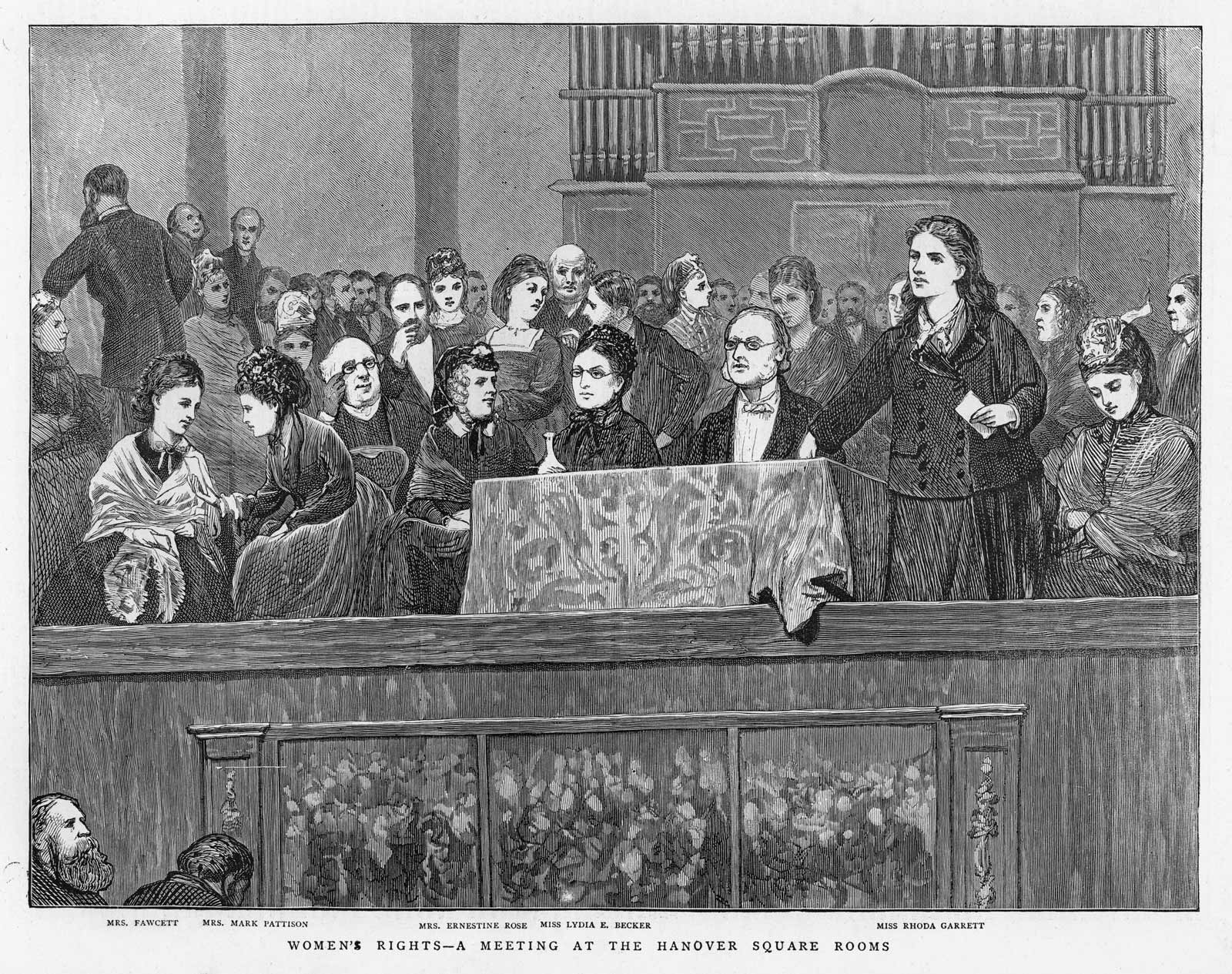

More importantly, Rose advanced remarkably provocative ideas. An immigrant from Poland, a communitarian socialist, an atheist, and a Jew, she was more “ultraist,” to use a then-faddish term, than anyone she shared a stage with. Susan B. Anthony wrote in her diary in 1854: “Mrs. Rose is not appreciated, nor cannot be by this age—she is too much in advance of the extreme ultraists even, to be understood by them.” Consider that a challenge; more than a century and a half later, it’s up to us to appreciate and understand this ultraist—and to make use of her example.

“My creed is, that man is precisely as good as all the laws, institutions, and influences allow him to be,” she said in 1853. It may have been as a Jew that Rose learned to respect the power of law. Rose spent her childhood immersed in Jewish texts, though she rarely talked about that as an adult; any reader of the Talmud will recognize the conviction that ethical individuals are the products of ethical legal systems, or, as she put it elsewhere, “We have hardly an adequate idea of how all-powerful law is in forming public opinion, in giving tone and character to the mass of society.” The rabbis never meant to apply this principle to women, whom they considered inferior in ethics as in most other things, but Rose turned it into a rejection of the biological determinism that had a lockhold over women’s lives and opportunities.

“What has man ever done, that woman, under the same advantages, could not do?” she asked. She added, “Will you tell us, that women have no Newtons, Shakespeares, and Byrons? Greater natural powers than even these possessed may have been destroyed in woman for want of proper culture, a just appreciation, reward for merit as an incentive to exertion, and freedom of action, without which, mind becomes cramped and stifled, for it can not expand under bolts and bars.” Note that this was seventy-eight years before Virginia Woolf expressed the same idea in A Room of One’s Own.

*

Ernestine Potowsky was born in 1810 in the Jewish quarter of a small Polish city named Piotrków Trybunalski, the only child of extremely religious, probably Hasidic, parents. (Ernestine was almost certainly not her original name, which would have been Yiddish, though her Polish name could have been Ernestyna.) Her father—by her account, an eminent rabbi—may have been disappointed that he had no son; in any case, he gave her a boy’s education in Hebrew and Torah, an unusual though not unheard-of undertaking. The Jewish mode of textual interrogation seems to have taught this brilliant child an extraordinary independence of mind. At fourteen, she “renounced her belief in the Bible and the religion of her father,” according to one nineteenth-century profile. When she was fifteen and a half, her father arranged a marriage for her. Rather than submit to matrimony, she traveled alone to Germany—an almost suicidally heroic undertaking for a sixteen-year-old girl at the time.

I can’t think of another woman in history who reinvented herself as often and with as much cool audacity. Settling first in Berlin, Rose somehow managed to meet and move among intellectuals,and then, moving to London, became a personal disciple of Robert Owen, the founder of British communitarian socialism. After making the passage to New York, she joined the highest circles of freethinkers there. In 1839, she struck one of her first blows for women’s equality at the Thomas Paine Society, where secularists gathered to honor the birthday of the founding father, by then widely reviled for his strident atheism. When she discovered that the Paine Society didn’t allow women to join the dinner and admitted them only to the ball afterward, she declared, “I thought Paine’s Rights of Man did not exclude women,” and organized an alternate, mixed-sex event. The following year, the society agreed to invite women to all the festivities. She later became one of the main organizers of the annual celebration.

Advertisement

Rose didn’t abandon free thought when she took up women’s rights. She just added the oppression of women to her bill of particulars against religion. “Superstition keeps women ignorant, dependent, and enslaved beings,” she’d say. “The churches have been built upon their necks.” Remarks like that didn’t always go over well. At one debate between believers and freethinkers at the Hartford Bible Convention in 1853, she exhorted women to “trample the Bible, the church, and the priests under your feet.” Male students from a nearby seminary stood up and hissed and shouted, finally extinguishing the lights in the hall. She stood calmly amid the chaos until the gas was lit again, then chided her hecklers: “Yes, you are fit representatives of your book, you illustrate your religion by your mobocracy!”

She also lectured on abolition, sharing stages with the likes of William Lloyd Garrison, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Frederick Douglass, and Sojourner Truth. Eventually, she became an indispensable part of the leadership of the movement for women’srights.

*

Ernestine Rose’s defining trait was nerve. She and her husband, another Owenite and a silversmith named William Rose, landed in New York in May 1836. Less than six months later, the twenty-six-year-old with curly hair and a Yiddish accent was going door to door with a petition urging passage of a bill newly introduced in the New York state legislature by a judge who was another freethinker. It proposed that married women be allowed to hold property in their own names. It seems that Rose sent in the first petition supporting the measure. It bore five signatures. “Some of the ladies” who opened their doors “said the gentlemen would laugh at them,” she recalled later. “Others, that they had rights enough; and the men said the women had too many rights already.” But she kept circulating petitions and sending them to Albany.

Four years later, she joined forces with Paulina Wright Davis, who had been up to the same thing in Utica, New York. In 1844, they met Stanton, who by then was also lobbying for the bill. The Married Women’s Property Act finally passed in New York in April 1848. Though history books record Stanton’s July 1848 convention in Seneca Falls as the foundational moment of the American women’s rights movement, Rose thought that her early solitary pavement-pounding was when it really began. One reason Stanton and friends called the Seneca Falls convention was that they felt encouraged by their legislative victory. Rose didn’t attend; the convention was a small, local, and hastily-arranged affair. Once it attracted attention in the press, though, she quickly recognized its import.

Why did Rose, a socialist, make the defense of property rights her first big cause? It’s tempting to look to her own life for an explanation. One anecdote from her youth is telling—so telling it may be, as journalists say, too good to check. (It’s also uncheckable, given the state of nineteenth-century Polish records.) After her mother died, at a date unknown, Rose inherited a large sum of money, though it was pledged by her father as a dowry to the fiancé he had chosen. The contract stipulated that the young man got to keep the money even if Rose did not marry him. “In vain did she throw herself at the feet of her fiancé,” wrote the French journalist Jenny d’Héricourt, “declaring that she did not love him and would never love him.” The fiancé, unmoved, filed suit in a Polish court in the town of Kalisz to gain possession of the dowry, and she drove out in a sleigh to argue against him. At this point, the story takes a fairy-tale turn. Rose had driven out “in the dead of winter,” d’Héricourt recounted, and her sleigh broke down. The driver wanted to wait for morning to resume their journey, but that was when the hearing was scheduled to begin, so Rose insisted he fetch someone to fix the problem.

“Enveloped in furs, the courageous child remained by herself from half past eleven at night until four the next morning,” d’Héricourt wrote. Rose reached the court in time, pled her case, and won “by convincing the judges that [she] should not have to pay with her property for an engagement entered into against her will.” Rose went home and, she later declared, gave most of the money back to her father, since she had no use for wealth. She spent the rest to get herself to Berlin.

Advertisement

A less fanciful explanation for Rose’s interest in wives’ property rights is that she was a businesswoman. In Berlin, the enterprising teenager invented an air freshener—yes, really!—and supported herself by selling it. It consisted of perfumed papers that, when burned, masked the foul smells that hung about unventilated Berlin apartments. In New York, Ernestine mixed and sold cologne out of the same shop where William made and repaired silver wares. As it happens, William Rose was a gentle soul who adored his wife and would never have encroached on her earnings; indeed, his trade helped subsidize the cost of her being on the lecture circuit. But Rose knew all too well that she’d have had no legal recourse if he had insisted on making her money his.

Under the British and American common law of marriage at the time, known as coverture, wives ceded their legal identities to their husbands, thereby forfeiting all claim to wealth or property they may have owned before the wedding and everything they earned or acquired after. A husband could designate his children as his heirs, leaving his wife a pauper upon his death. If he died intestate, she could inherit a small portion of his assets, but only as long as she lived; she couldn’t leave that bequest to her own relatives. The law did let a widow keep a few things. In an 1853 speech, Rose sardonically listed some of them as the audience laughed with knowing glee: “Her own wearing apparel, her own ornaments, proper to her station, one bed, with appurtenances for the same; a stove, the Bible, family pictures, and all the school books; also, all spinning-wheels and weaving looms, one table, six chairs, tea cups and saucers, one tea-pot, one sugar dish, and six spoons.”

Rose’s socialist education let her see husbands’ appropriation of wealth from their wives as part of a larger pattern of exploitation. Husbands—like employers and nations—grew rich on womens’ unpaid labor. Owenism was virtually the only social philosophy of its day that understood domestic labor as labor, a value-generating activity that made paid labor possible. Not even Marx would concede the point half a century later. Owen observed that marriage enslaved women economically as well as legally. He imagined communities in which household work would be shared between the sexes. Owen’s dream never came to pass, even in the utopian communes founded in his name; the women who joined them usually wound up doing housework as well as field work (as remains the case today), one reason the experiments failed.

Although married women’s property acts had passed in twenty-nine states by the end of the Civil War, these too fell short. The laws granted wives only the right to hold onto preexisting assets and money earned outside the home, rather than giving them a share in the wealth jointly produced in a marriage thanks in large part to their work in the home. But to Rose and the others fighting the battle—Stanton was equally enthusiastic about property rights—this was a start. They soon launched another campaign. They sought a joint property regime that treated marriage as a business partnership. It took as its model the gendered economics of the old-fashioned family farm, in which the food preparation, sewing, and cleaning done by women contributed to the general well-being as fully as the sowing and harvesting done by men. “The in-door business is as requisite as the out-door, and if it is sometimes easier, it is sometimes a great deal harder,” said Rose. So why should the conjunction of indoor and outdoor rank “beneath even a common copartnership?”

The early feminists didn’t challenge the separation of spheres that assigned women to “in-door” work, something twentieth-century feminists would criticize them for, but they did assert that women could do any job a man could do, given the education. But in the concept of joint property, Rose, Stanton, and the others came up with an idea that was before its time, and in some ways before ours. They found a way to account for and reward unpaid household labor, a feat our marital laws do only fitfully and at the whim of the courts. In a 1994 essay in the Yale Law Journal, “Home as Work,” the legal historian Reva Siegel explained how the women’s movement failed to make joint property the law of the land, and argued that we live in the shadow of that failure even now. Joint property slipped off the agenda after the Civil War when the women’s movement made a conscious decision to focus all its energy on winning the vote.

At the same time, industrialization heightened the divide between waged and unwaged work and equality came to mean equal pay, not equal respect and value for women’s (often upaid) work. The turn-of-the-century “modern” woman saw family and household maintenance as an obstacle to freedom, not a job worth demanding money for. As Siegel put it:

While work performed in the household had dignity in the family-based economy of the early nineteenth century, the social organization of housework now marked it as “women’s work,” an atavistic practice of doubtful economic utility that wives seeking autonomy would have to escape.

Had joint property become a guiding principle of marital law, caregivers, most of whom are women, might be in better shape than they are today. Nowadays, women who “stay home with the kids,” as well as the men who do the same, are impoverished by their absence from the world of “work.” Conservatives consider the idea of putting a price on the labors of love demeaning. Even some feminists dismiss it as unrealistic. But joint property didn’t call for cash payment, just a consistently equal share in the wealth of the household. Today, only nine American states follow “community property” laws that more or less guarantee a 50:50 division of marital wealth in case of divorce; the other forty-one, the “common-law” states, follow the principle of “equitable distribution,” a vague term whose meaning varies case by case and judge by judge.

*

Ernestine Rose’s egalitarianism is also instructive. The most cosmopolitan and transatlantic of the American nineteenth-century feminists, she imbibed her democratic values in Europe while it was in full revolutionary ferment. Her Jewishness—and foreignness—must also have affected her. Rose grew up in a Poland rife with anti-Semitism, and though Americans didn’t actively slaughter Jews, as Poles sometimes did, Americans did sneer at Jews. Rose once had a fiery exchange of letters with Horace Seaver, a long-time friend and the editor of the atheist Boston Investigator, which had published several of her speeches, after he wrote a series of editorials that began by attacking ancient Hebrews and wound up denouncing modern Jews. They clung to their “absurd rites and ceremonies,” he wrote. Their religion was “bigoted, narrow, exclusive and totally unfit for a progressive people like the Americans.”

By the time Rose reached the United States, she had witnessed the French Revolution of 1830, an anti-monarchical and anti-clerical uprising, during a brief sojourn in Paris. She had joined the Owenite Association of All Classes of All Nations in London and become a popular speaker at its meetings—though the young woman ascended to the podium, she once recalled, only after she had “washed and put away with her own hands all the dishes used to make and serve tea.” Rose invited European feminists to American women’s rights conventions, and spoke out about events overseas, such as the Irish Famine and the European uprisings of 1848–1849. She called for the United States to grant asylum to “martyrs of freedom” such as the Hungarian liberal nationalist Lajos Kossuth, his Polish counterpart Józef Bem, and the Italian revolutionary and unifier Giuseppe Mazzini.

Relief from oppression for one group, she held, was relief from oppression for all. “Emancipation from every kind of bondage is my principle,” she said at an anti-slavery convention. “I go for recognition of human rights, without distinction of sect, party, sex, or color.” Rose was not the first to use the phrase “human rights” to express the Lockean idea of natural rights—William Lloyd Garrison probably coined the expression about a decade earlier—but Rose had toured with him and knew a good phrase when she heard one. Once, when Susan B. Anthony wanted to characterize a meeting as “a woman’s rights convention,” Rose declared that it was a human rights convention, too, and “the men ought not to be afraid to speak out also.”

*

Why didn’t Rose make it into the history books? There’s a long list of reasons. The Civil War heightened incivility, causing flare-ups of nativism and anti-Semitism, both of which marginalized Rose. As spirited as she was, she had never been physically strong—she appears to have suffered debilitating rheumatism—and over the course of the 1860s, she grew frailer, leading her to speak less and to withdraw from the front ranks of the women’s movement. Rose and Stanton had long shared a reputation as the leading speakers of the movement, but Stanton soon eclipsed Rose.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the American free-thought movement became even less popular than it had been in the first half. With typical obstinacy, Rose published her only book, A Defense of Atheism, in 1861. Stanton, by contrast, identified as Christian and wore a large cross. Late in Rose’s life, a journalist wrote that her “honest, earnest conventions in regard to theological matters” excluded her from “the list of those ‘eminent’ women who have distinguished themselves on the lecture platform in their chivalric crusade against all forms of slavery.”

When the Civil War ended, a smaller civil war tore the women’s movement in two. The fight turned on the question of whether the women’s movement should drop its demand for universal suffrage until black men got the vote. Rose, Stanton, Anthony, and others insisted on continuing to press for women’s right to vote. Other feminists and some allies, including Frederick Douglass, counseled patience, saying that the Negro’s emancipation was a matter of “urgent necessity.” But when Congress passed the Fourteenth Amendment, which enfranchised only “male citizens,” the faction that included Rose grew embittered.

Some in the group turned against the abolitionists and even became actively racist. Stanton herself went to startling extremes. “It becomes a serious question whether we had better stand aside and see ‘Sambo’ walk into the kingdom first,” she said in 1867 (the “kingdom” being the “celestial heaven of civil rights”). Ugly anti-immigrant sentiments also infected her speeches. How could it be, she asked, that “Patrick” (that is, an Irish immigrant), “Hans” (a German one), and “Yung Tung” (a Chineseman) would get to vote before well-heeled American-born women like herself. “If all men are to vote,” Stanton declared, “black and white, lettered and unlettered, washed and unwashed, the safety of the nation as well as the interests of woman demand that we outweigh this incoming tide of ignorance, poverty, and vice, with the virtue, wealth and education of the women of the country.” (It’s worth noting that Stanton came from a wealthy family that had owned slaves.)

Stanton and Anthony went on to strike a devil’s bargain with a notorious racist, George Francis Train, who championed women’s rights as a way to undermine black suffrage. He gave Stanton and Anthony money to start a weekly paper, which they called The Revolution. It ran from 1868 till 1872 and mixed its feminism with calls for “educated suffrage,” which was an underhanded way to block the black vote. The Revolution once ran an article that recommended keeping “the Jews and the Chinese” out of the country. It described Jews and Chinese as “voracious, knavish, cunning traders,” and Jews in particular as “a race of mere bloodsuckers.”

Rose shared Stanton and Anthony’s fury at the inclusion of the word “male” in the Fourteenth Amendment, but she steered clear of their racism—with one unfortunate exception. Rose never opposed the black vote. She framed the problem a different way: Why protect only the Negro man? “Why do they not at the same time protect the Negro woman?” Sojourner Truth agreed with Rose: “If colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, they will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before,” Truth said at an 1866 convention. And yet, Rose did engage in immigrant-bashing, once, in 1869: “We might commence by calling the Chinaman a man and a brother, or the Hottentot, or the Calmuck [meaning Mongolians], or the Indian, the idiot or the criminal, but where shall we stop? They will bring all these in before us,” she said.

This lapse was clearly a betrayal of her own universalist principles, but we might allow some mitigating circumstances. Rose was unwell at the time and had become more or less a member of Stanton’s entourage. She gave that repugnant speech at the last American convention she attended before she left the United States. Three weeks later, she returned to Europe with William, never to move back to the US, though she did visit New York a few times. She never elaborated on why she left. Carol Kolmerten, in The American Life of Ernestine Rose (1999), speculates:

Perhaps Ernestine Rose just got tired of the internecine warfare. Perhaps she despaired when her closest colleagues resorted to racism… Perhaps she just lost her patience with everyone who could not see the logic of her point of view: that in a republic based on freedom, women and black men should both be fully recognized as human beings. Perhaps the anti-Semitism and anti-immigrationist sentiments that were always lurking beneath the surface of many woman’s rights arguments finally demoralized her.

Arriving in France, the couple traveled to spas, where Rose “took the waters.” After a year, they settled in England, first in Bath, then London. Rose renewed old friendships and made new connections with suffragists, Owenites, and freethinkers (the British free-thought movement had expanded over the previous two decades, unlike the American one). She became a lecturer again. She published letters in American journals. She kept up her contacts in the United States, was the subject of nostalgic reminiscences in the American press, and was even appointed to offices in American women’s associations in absentia. After her health finally forced her to retire in 1872, feminists and freethinkers on both sides of the Atlantic wrote glowing tributes to her.

But the American women’s movement moved on. In the 1870s, Stanton and Anthony began compiling a History of Woman Suffrage and asked Rose to contribute an autobiographical essay. Rose’s response did nothing to promote her reputation. She wrote back, “I have nothing to refer to. I have never spoken from notes; and as I did not intend to publish anything about myself, for I had no other ambition except to work for the cause of humanity, irrespective of sex, sect, country, or color… I made no memorandum of places, dates, or names.” Anthony printed that letter, along with a short biographical sketch of Rose by journalist Lemuel Barnard, and some memories of her own.

In 1882, William died, and from then until Rose’s death in 1892, she lived in isolation, seeing only a few friends who described her as sad and lonely. Surprisingly, she left most of her small estate to three half-nieces from the Polish family she almost never spoke of—daughters of the daughter whom her father had had with his second wife. And then she vanished from view for almost a century.

*

Why resurrect Rose now? “As a Jew, as an atheist, as a woman and a foreigner, Ernestine Rose did not fit into the early-twentieth-century narrative of US history,” writes Bonnie S. Anderson in The Rabbi’s Atheist Daughter (2017). She was rediscovered by feminists during the 1970s, but she never received her full due, notwithstanding Kolmerten and Anderson’s excellent biographies and a collection of speeches and letters titled Mistress of Herself (2008), edited by Paula Doress-Worters (though Rose extemporized and kept no notes of her speeches, their texts were preserved in the proceedings of women’s-rights and abolitionist conventions, and she wrote a great many articles and letters to editors). I have drawn heavily from all three books for this essay; there is also a handful of scholarly papers as well as a 1959 biography, in English, by the Yiddish poet Yuri Suhl that insightfully imagines life in her early Jewish milieu but invents dialogue and gives no sources.

Certainly, there was her mastery of an art that today is in need of revival: political oratory. It goes without saying that few of our public lecturers could hold rapt a thousand people for an hour, as Rose did in one of her greatest speeches, at Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1851. There is no current feminist leader—no leader of any kind—of whom it can be said that “her eloquence is irresistible,” as one audience member observed after one of her speeches. Her oratory “shakes, it awes, it thrills, it melts—it fills you with horror, it drowns you with tears.” Imagine what our politics would be like if there were a candidate who could make the case for gender equality as eloquently as Rose did. “Humanity recognizes no sex; virtue recognizes no sex; mind recognizes no sex; life and death, pleasure and pain, happiness and misery, recognize no sex,” she said at that speech. “Like man, woman comes involuntarily into existence. Like him, she possesses physical and mental and moral powers… like him she is subject to all the vicissitudes of life.”

Then, too, we could take stock of how Rose’s heterogeneous political education enlarged her understanding of women’s lot. As a socialist, she saw that matrimony robbed women of the fruits of their reproductive and domestic labor. As an Enlightenment-style rationalist, Rose insisted on freedom of thought and speech, even when it was her fellow feminists who tried to shut her up. America in those days was in the middle of the evangelical revival known as the Second Great Awakening, and it was considered unwise to offend the devout. Besides, a great many abolitionists and a few feminists were ministers themselves. Rose was an inveterate contrarian. In the 1860s, scores of her comrades (including, astonishingly, Robert Owen, as well as feminist stalwarts such as Lucretia Mott and Sarah Grimké) became entranced by spiritualism, a quasi-religious endeavor that involved trying contact the spirit world through mediums. Rose immediately denounced them as foolish. “I dislike to have to do with ghosts,” she wrote. “There is not substance enough in them to form an idea from, or base an opinion on.”

If we were to airlift Rose out of the past and drop her into the present, we’d probably put her in the company of liberal feminists like Susan Okin and Martha Nussbaum, who themselves belong to the tradition of classical liberals like Mary Wollstonecraft, Harriet Taylor Mill, and John Stuart Mill. A liberal who is also a socialist may sound like a confused soul, but remember that Rose was a freethinker above all. She combined a passion for personal and political autonomy with the Rawlsian belief that the just state should fairly distribute the benefits and burdens of social co-operation. Rose understood as well as anyone (and certainly better than Rawls) that sexism prevents fair distribution of this sort, but her battle was against structural injustices—against patriarchal laws, institutions, and traditions, not against bad men. She would have had no use for the kind of illiberal feminism that might, for instance, advocate the curtailing of the civil liberties or free speech of individual men because men, as a class, enjoy more power and privilege than women. “It is from ignorance, not malice, that man acts toward woman as he does,” she said.

Rose used to say that she came to America because of her love for the Declaration of Independence, with its assertion of universal enfranchisement, even if the document was incorrectly understood as applying only to white men and, in some states, only white men of property. “I ask for the same rights for women that are extended to men,” she said, “the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; and every pursuit in life must be as free and open to me as any man in the land.”