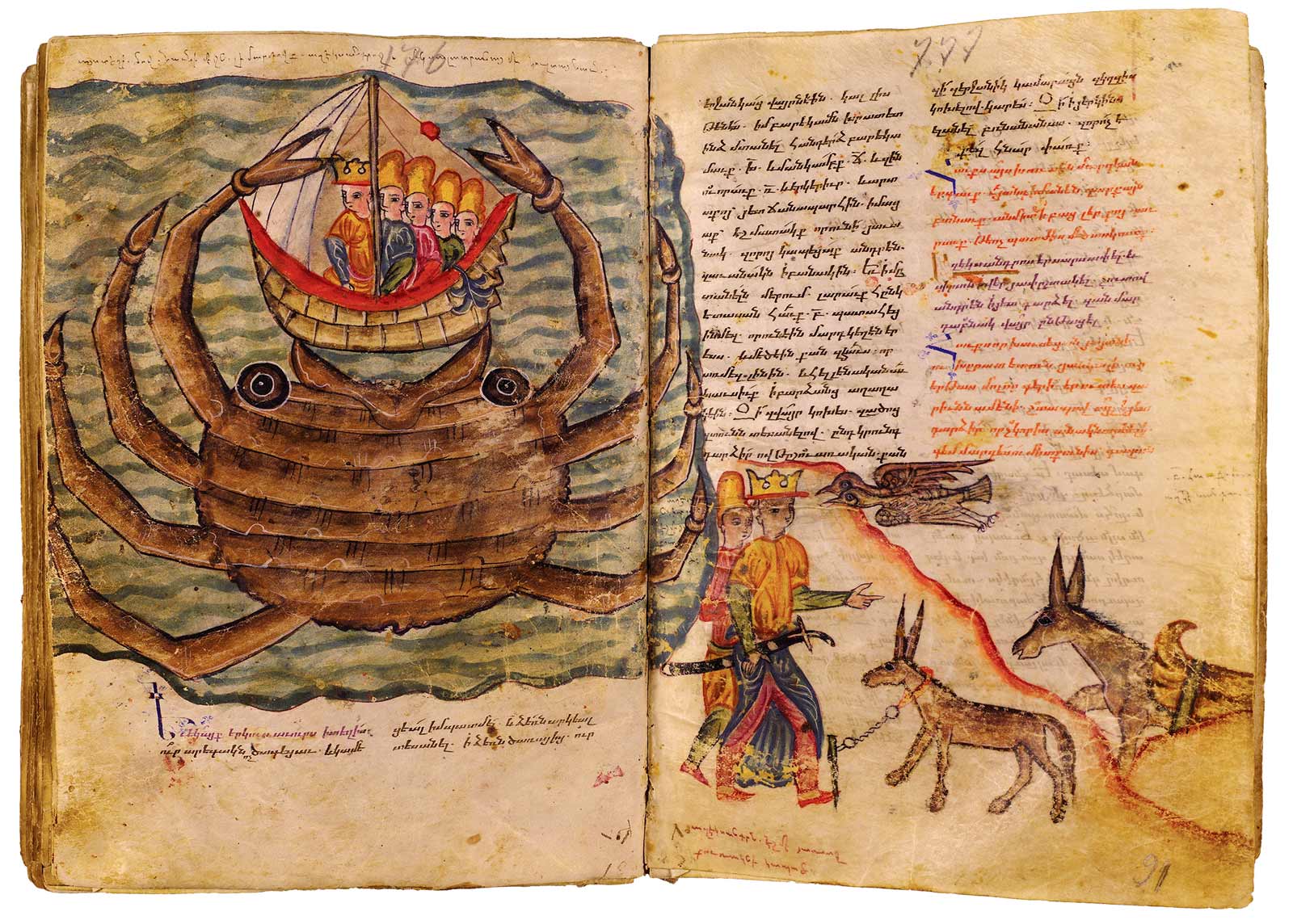

One small display in an exhibition can grab you by the collar. In the case of “Armenia!” at the Metropolitan Museum, it was the image of a spherical wide-eyed crab in a ridged armor swallowing Alexander the Great, along with his ship and retinue, set against a wavy sea that might have been drawn by a child. It is attributed to Zak‘ariay of Gnunik and appears in an illuminated manuscript of the Alexander Romance (1538–1544), the legends surrounding the exploits of Alexander the Great, much loved by Muslims, Orthodox Christians, and Armenians alike. Dr. Helen Evans, the Met’s curator of Byzantine Art, told me, “That crab is too good not to be recognized as the type of art we don’t expect from East Christians.” And it most definitely wasn’t, she added, “the stiff art of the Byzantines that Vasari disapproved of.” Giorgio Vasari, the Italian architect, painter, and historian, author of Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects (1550) Western culture’s first art historian, who coined the use of the term “Renaissance,” unfairly saw in Byzantine abstractions, coming after Greek and Roman art, a decline in skills rather than an artistic choice.

The exhibition opened with the Primate of the Eastern Diocese of the Armenian Church of America blessing the occasion by singing, with two others, an allelujah in a voice that filled the galleries with the sound of Armenian liturgical chants. There are one hundred and forty objects in the show, including jewelry and reliquaries, as well as church models, illustrated manuscripts, and textiles for liturgical use—one fourteen-foot-long red and gold “omophorion” of interwoven square crosses is reminiscent of the Russian avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich’s crosses on canvas and icons on paper. The objects on display range from the fourth to the seventeenth centuries and represent the different regions Armenians inhabited, from their homeland at the base of Mount Ararat, to the kingdom of Cilicia, and further East to New Julfa, in Iran. Armenia was one of the first states to adopt the Christian religion—as early as AD 301—and its history has been defined both by this, its status as an outpost of Eastern Orthodox religion surrounded by Muslim neighbors, and by its role in establishing trade routes from China and India to Western Europe, and from Egypt and the Holy Land to Russia.

The exclamation mark following the word “Armenia” in the exhibition’s title—Evans’s idea—was meant to convey her surprise that Armenian art and culture aren’t studied more or better known. A champion of what she calls “this edge of Byzantium that is Armenian art and culture,” Evans has been wanting to assemble a show such as this one ever since she began researching her dissertation on Armenian manuscripts of the kingdom of Cilicia almost forty years ago. (She has also curated other Byzantine blockbusters at the Met: “The Glory of Byzantium” (1997), “Byzantium: Faith and Power” (2004), and “Byzantium and Islam” (2012).)

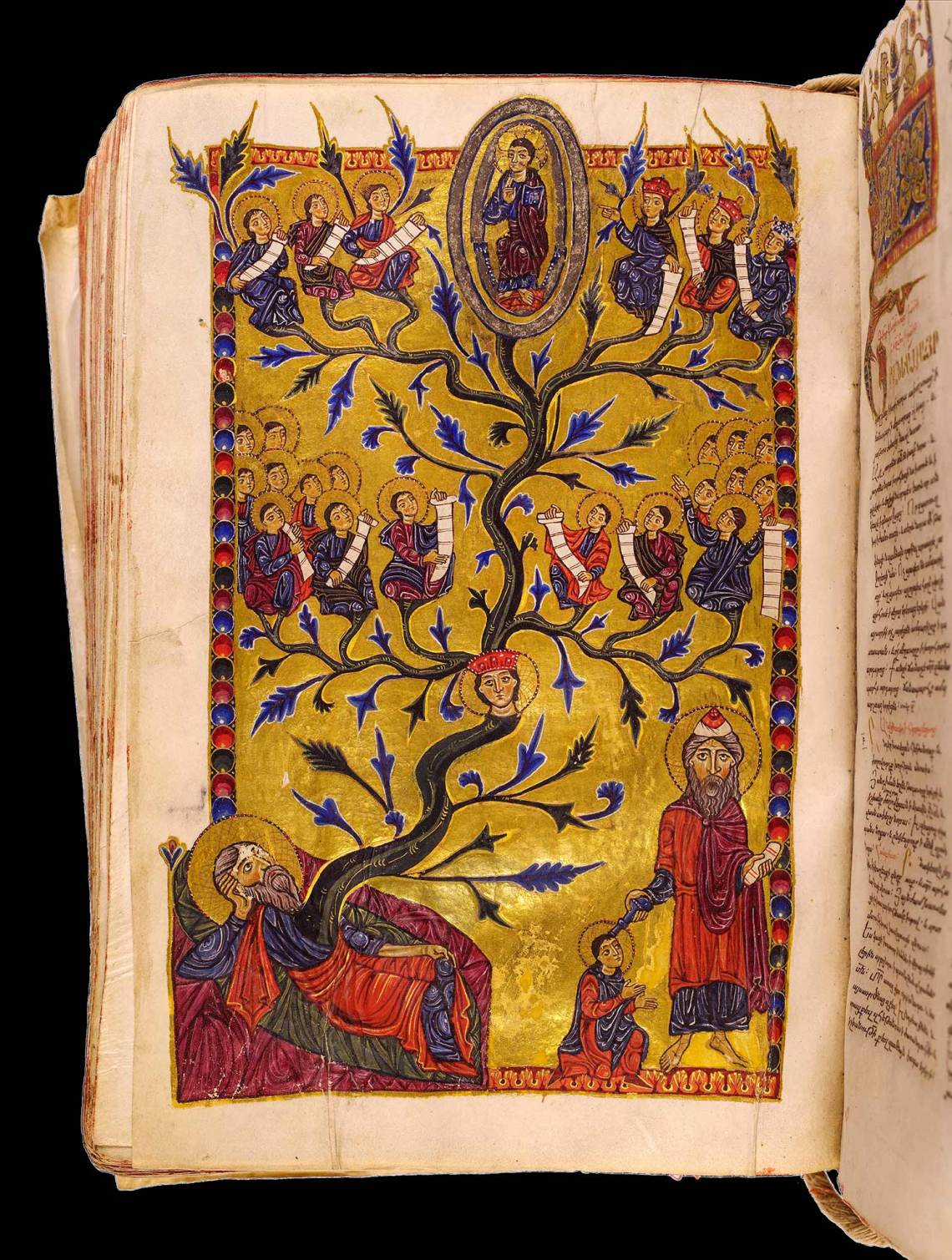

At the center of the Met’s installation is a cross-like construction of intersecting walls onto which large color images of the churches of the Monastery of Sevan (ninth century or later) before a placid, mist-shrouded lake are projected. Armenian liturgical music plays in the background. Armenians had only a spoken language until an alphabet was created in 405 and was used in translations of the Bible and liturgy, which further reinforced the Christian religion in Armenia. The Armenian Apostolic Church has been seen as steward of Armenian national identity, and that explains why religious subjects have prevailed in Armenian art. Crosses—jewelled, painted, carved—are everywhere in this exhibition. Evans traveled to the Lori Province in northern Armenia to retrieve a massive one sculpted into basalt, a khachkar (from Lori Berd, of the twelfth–thirteenth centuries) that weighs 1,000 pounds. Khachkars—there are three in the show—are memorial cross stones used as Christian grave markers in medieval times, or to mark historical sites. At the foot of this one are bas-reliefs of the evangelists—a face that stands for Saint Matthew; a funny lion, more like a cat for Saint Mark; an ox head for Saint Luke; and the profile of an eagle for Saint John. All around the rectangular frame is a delicate wicker-weave motif of three cords intertwined remiscent of some Islamic ornamentation.

Advertisement

Sculpted miniature churches, sixteen to fifty inches high, used as ornaments over doorways and roofs, are among the most striking products of Armenian architecture on display. The Model of the Cathedral of Holy Etchmiadzin, the capital of Armenia (Vagharshapat, fifth–seventh century), looks like a stocky missile made of stone, with a large arrow carved into its base that points toward the heavens. Much of Armenian art appears to refer to an elsewhere, having to do with faith rather than place, that Armenians took refuge in throughout their harrowing history of forced displacements. Theirs is a story of “mobility and metamorphosis,” as the show’s introductory wall label reminds us.

The church model (or acroterion, which means “ornament”) at the Monastery of Bardzrak‘ash (Dsegh, Lori, tenth–thirteenth century), which is displayed at a slant that makes it look like an axonometric projection, is attached to a large roof tile and was made to adorn the top of the Monastery of Bardzrak‘ash. According to Evans, the Early Christian world had a long tradition of donors holding models of the churches they funded. Another church model (Siwnik‘, eleventh–thirteenth century) carved out of tuff, a porous volcanic rock not unlike pumice, is the most elemental of them all. Its rectangular entrance, opening onto a dark cave-like interior, is oddly inviting.

Regarding small churches, Dr. Evans told me of a thirteenth-century text referring to a site that was attacked by Mongols. The Armenians held out for six weeks, which, given the brutality of Mongol attacks, according to Evans, counted for something like twenty years. The Mongols were so impressed that they decreed that anybody who could fit into the church and its tiny courtyard would be saved. The Mongols were stunned because, though there seemed to be no room inside the little church, more and more people kept filing in. Then they saw that the priest inside the church was transforming people into doves that flew out the windows of the apse. Birds are everywhere in Armenian iconography and they symbolize risen souls. “The Armenians believe that birds carry souls to heaven,” Evans explained.

The first long gallery of illuminated manuscripts, where you’ll find the crab, displays an open Gospel Book from the Monastery of Manuk Surb Nshan: two black-hooded figures sit side by side within a finely, if minimally evoked, architecture—some turrets with green onion-shaped domes. The black-bearded man, who is a teacher, hands an inkpot and pen to his red-bearded student,” Two angelic figures right below them, holding a green and a red vessel, appear to be celebrating the occasion.

The Great Shah Abbas I of Persia, of the Safavid dynasty, responsible for moving his kingdom’s capital from Qazvin to Isfahan summoned Armenian artists and artisans, as well as merchants, to the new city he was building. About three thousand families had been deported from the Armenian town of Julfa in the Ottoman Empire, after the Shah reconquered it in 1603. There was a second deportation in 1606. Many drowned as they attempted to cross the Aras river. Julfa was then burned down to stop the inhabitants from ever wanting to return to it. (Some three hundred years later, the artist Arshile Gorky’s mother died of starvation in his arms after just such a death march in 1919 when Armenians were forced out of Eastern Turkey.) Sixteen large stones from the first church ever built in the holy city of Etchmiadzin are now kept in the summer altar of Gevork (St. George) Church in New Julfa, the city that the exiled Armenians founded as part of Isfahan, one of the thirteen churches still standing of the more than twenty originally built in the 1600s.

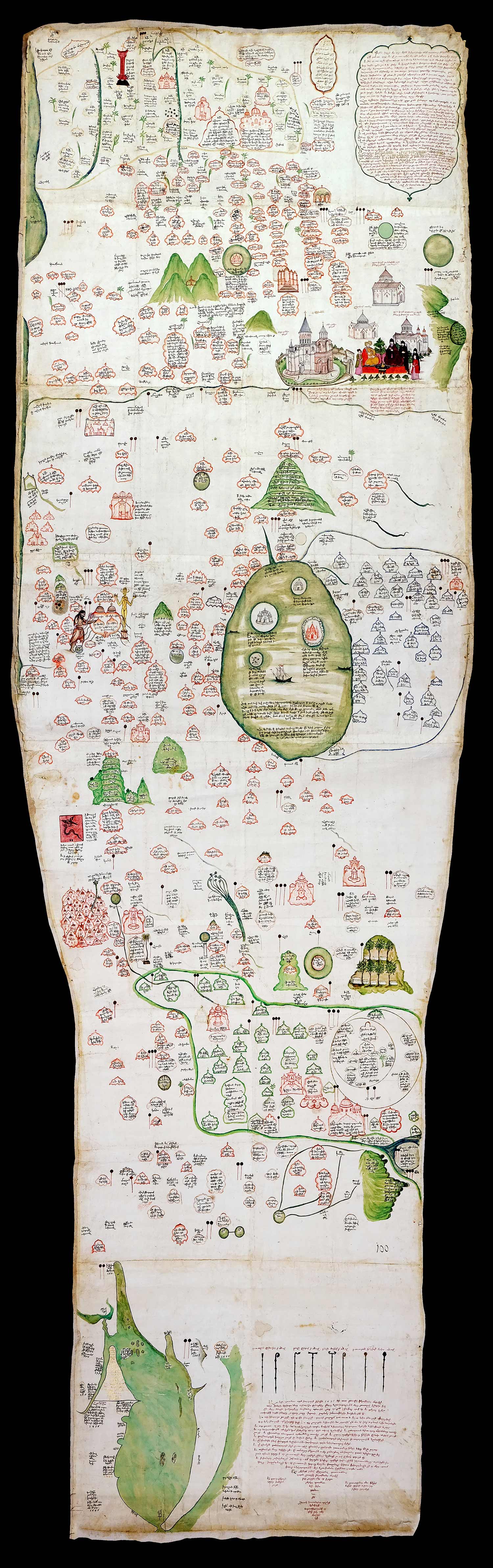

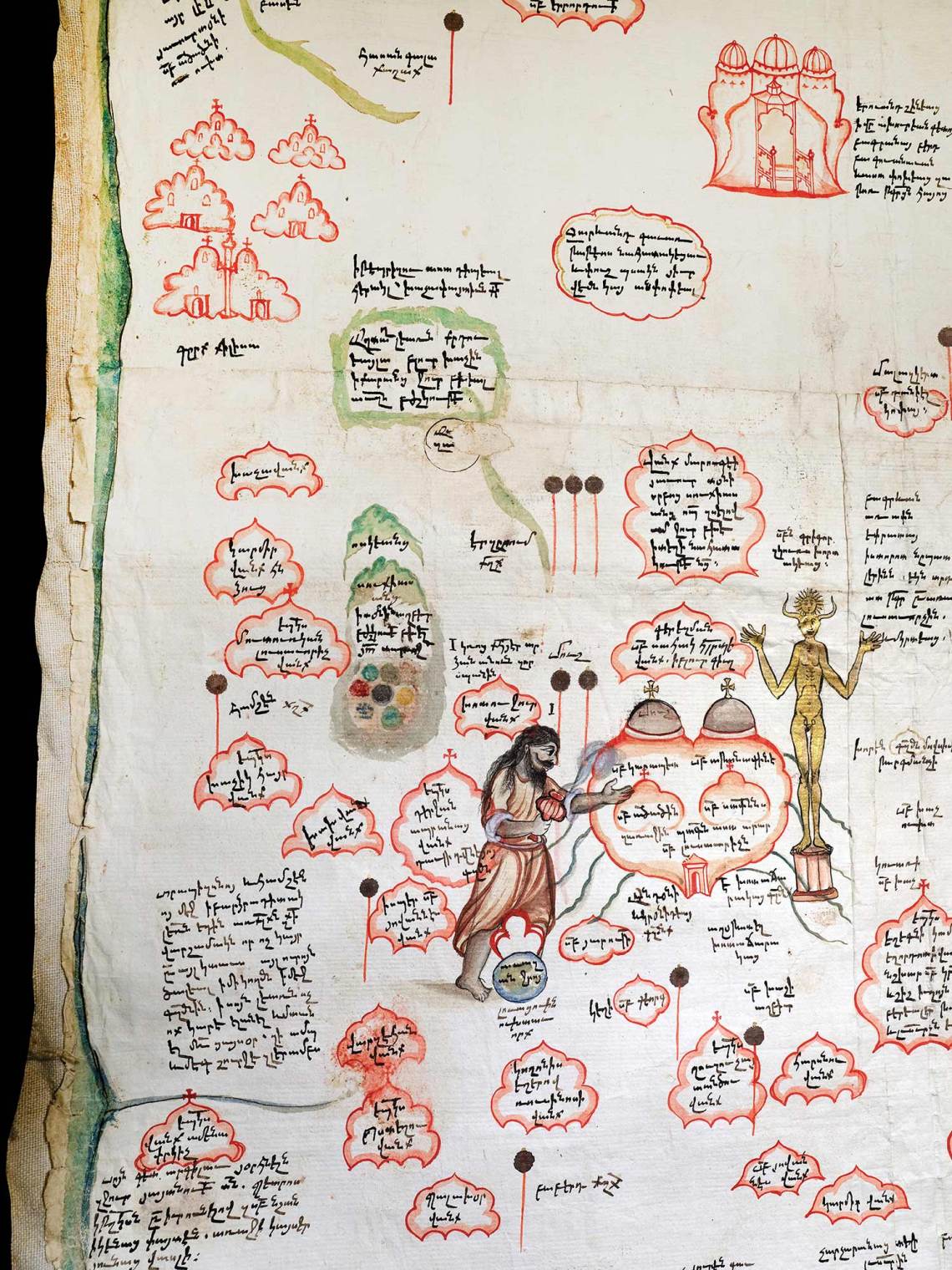

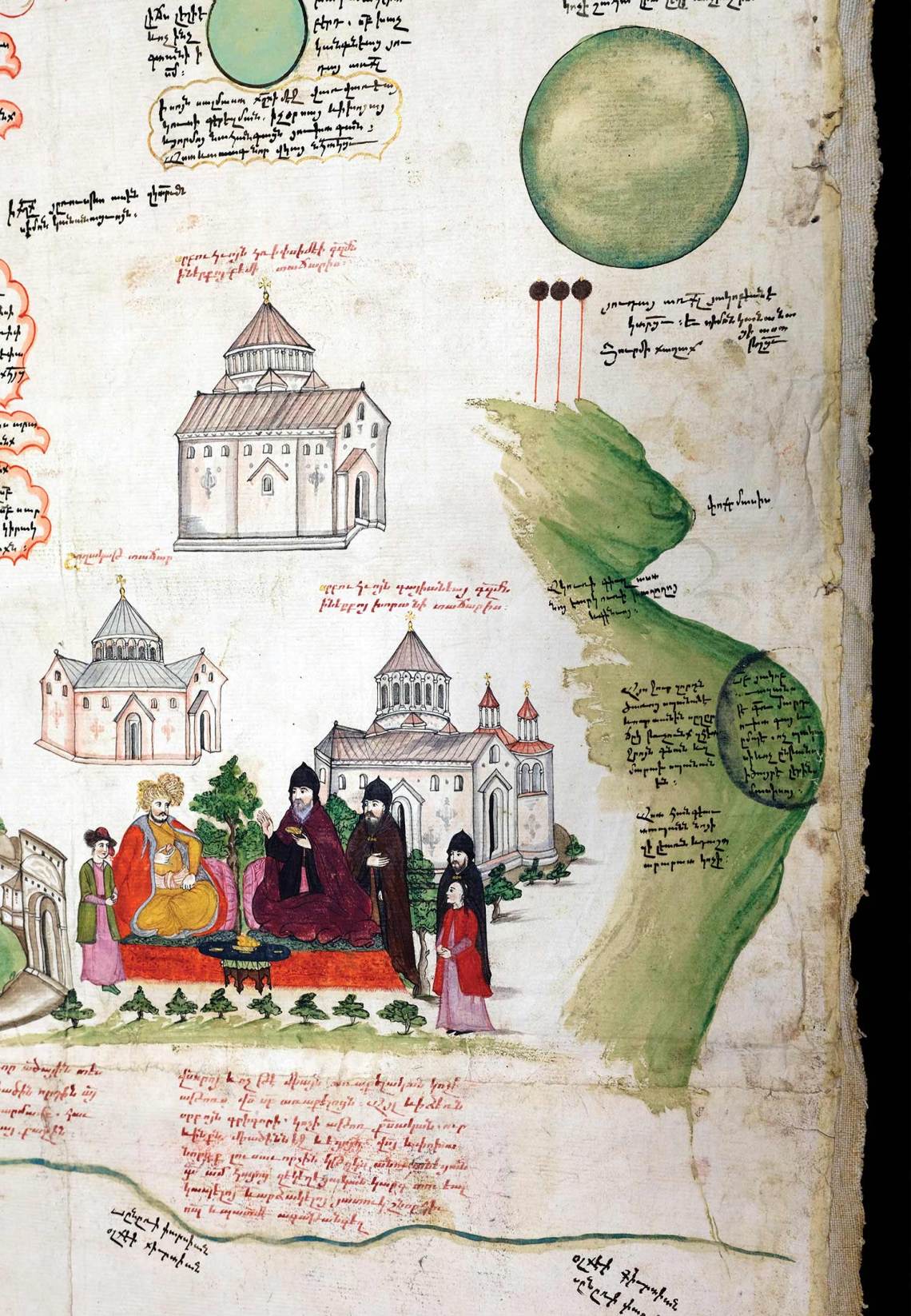

One of the most magnificent displays is the Tabula Chorographica Armenica (1691), a map that has hardly ever been exhibited, and which came accompanied by its own courier (as did most of the rare pieces in this exhibition) from the Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna. Approximately twelve feet by four, this spectacular piece of cartography is delicately colored and shaped like a cricket bat, narrower at the base, and has a multitude of inscriptions in green scallop-edged bubbles interspersed with occasional human figures. It charts the locations of nearly eight hundred sites, including diagrams of important Armenian churches in the Ottoman Empire, from Nishapur, in northeastern Iran, to the religious sites of Crimea. It was drawn by Eremia Ch‘elepi K‘eomiwrchean for Luigi Federico Marsili, a Bolognese aristocrat in the retinue of the Venetian ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, and was, we are told, a testament to his erudition. By the end of the seventeenth century Armenian communities were a substantial presence from London to Myanmar and from Amsterdam to Madras, and this map did not just illustrate the geographic reach of the Armenian presence, as the catalogue text points out, “it highlighted the Armenian networks of control through trade, culture, and religion.”

Advertisement

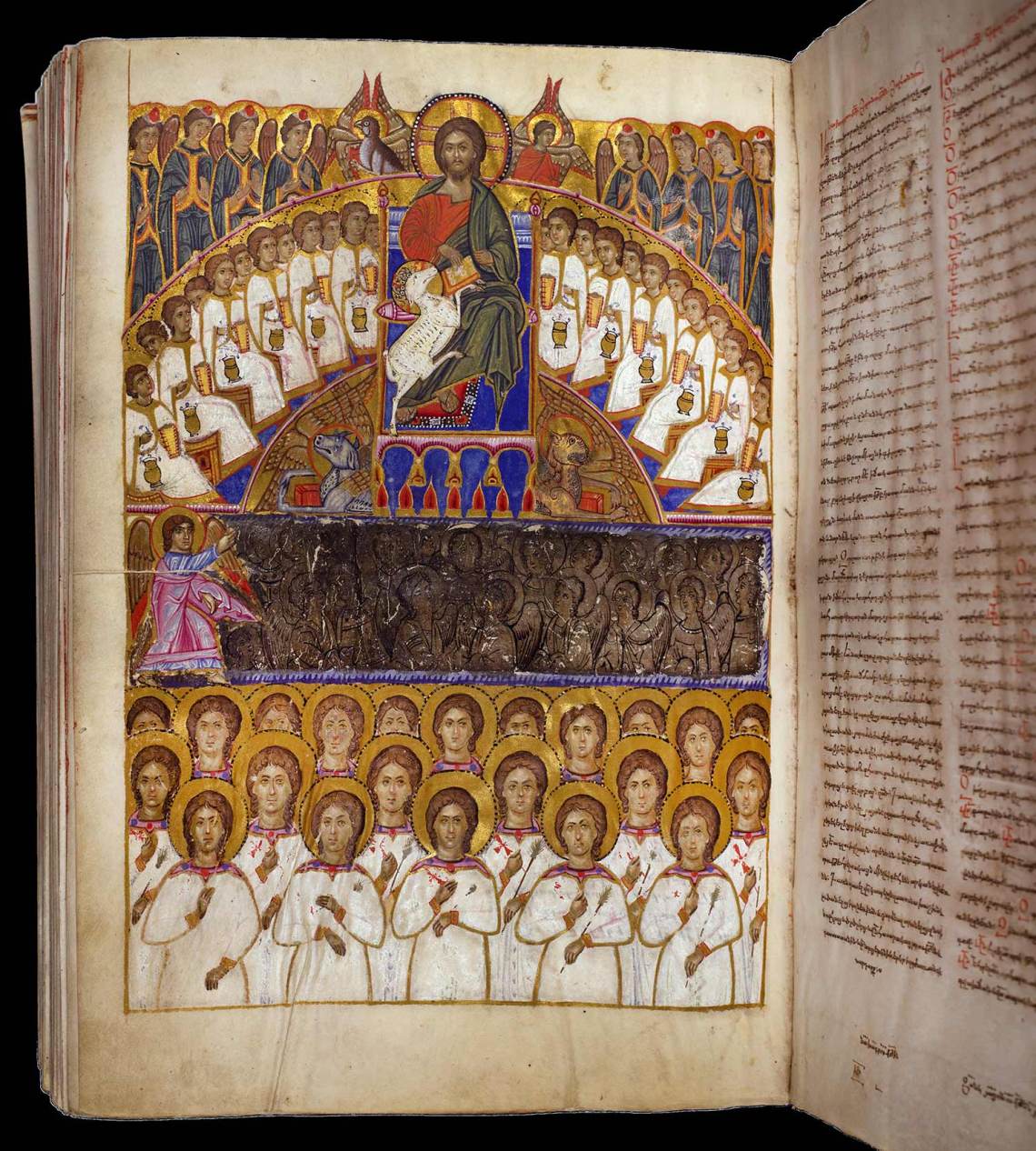

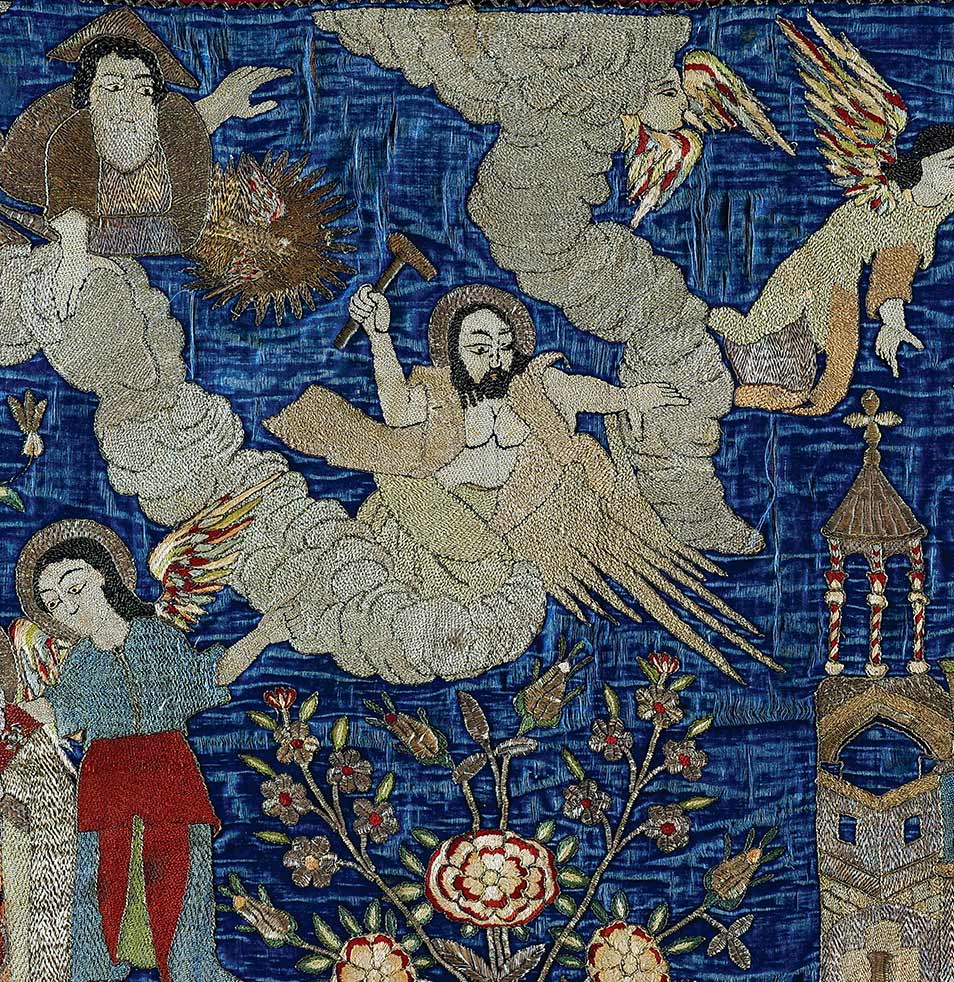

Another showstopper is the great liturgical curtain of Tokat (1689), also known as Eudokia, an eleven by eleven feet piece of printed pigment on cloth, from the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, Armenia. Keith Haring would have appreciated its repeated outlined shapes and graphic clarity. Rows and rows of identical figures kneel in devotion. The background is sand-colored, the figures of men are off-white, silhouetted in brown-black, dull red, or black-red, the colors of drying blood. Lines drawn from the base of their throats to their groins, and along their arms make their entire bodies into crosses. Their mouths are half-open, set in an “Oh!” Above them, insets of similar figures, only with robes more ornate, also kneel in rows.

An angel beneath a curlicued halo, and with what looks like a large beauty mark on one cheek, gazes down on the scene from the upper left-hand corner. An astonishing number of lanterns, variously decorated in red and white and repeated amid a proliferation of crosses, fill the top band of the curtain. On the left, set in an arch, is an image of the Virgin and Child, and to the right, within another arch, that of Christ on the cross. Large drops of blood, like rain drops, or magnified cartoon-like tears, flow down into a small pool by Christ’s nailed feet. The Virgin at his side appears to wipe away tears and wears a dress of white stars on a red background. Above the cross sits a red-faced sun, and on the left, a smirking moon. Flitting birds or souls flank the cross. And angels are everywhere, hovering more like obliging insects than transcendent creatures, over church cupolas and altars, their wings propelling them in all directions, lending a faintly lighthearted note to the whole. This flight, evoking incorporeality, is perhaps one of escape, and an angel in a red polka-dot dress makes for a consoling sight. But red is the color of blood, too, as this dazzling curtain never allows one to forget. Saints and prelates hold up chalices, full of wine—or of blood? Martyrdom and celebration, however you wish to see it. The effect is exuberant, enveloping. Ornament and repetition keep your eyes anchored, your mind engaged. Could Armenians have learned this subterfuge from Islamic use of abstract, repetitive ornament?

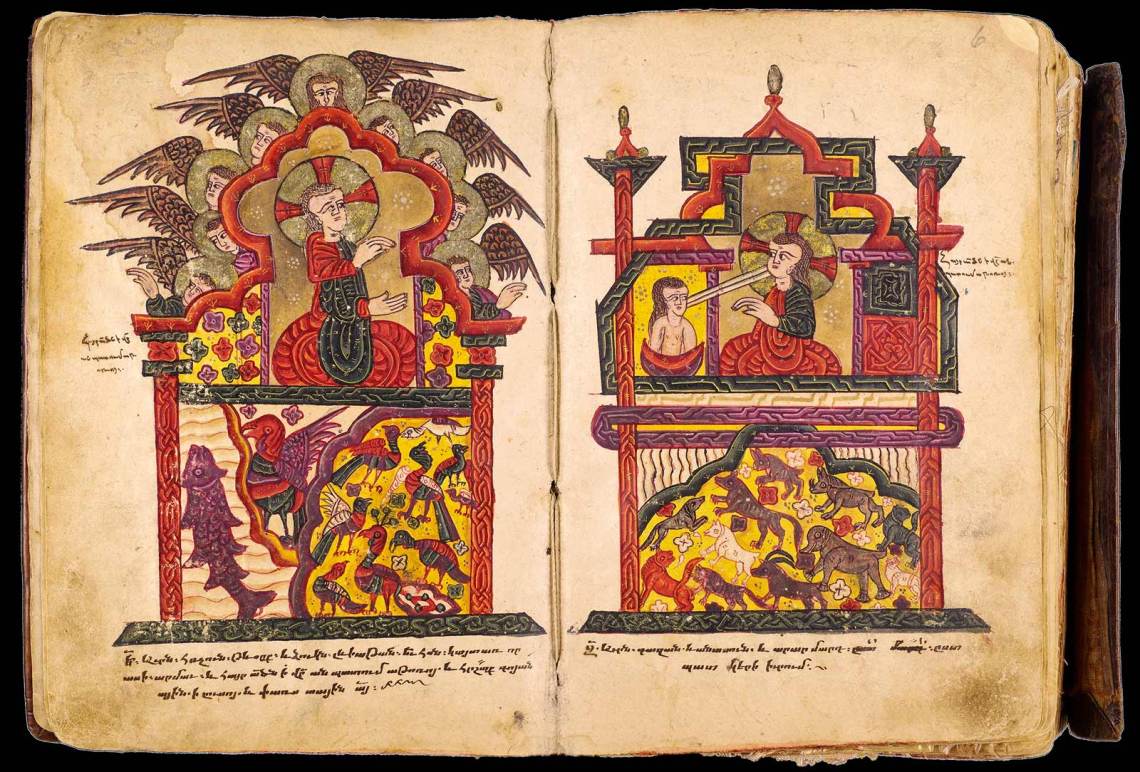

A detail of the “Last Judgment” (1703–1708), from the Cathedral of the Forty Martyrs (Aleppo, Syria), that appears in the exhibition catalog shows a body of water beneath land that has been cross-sectioned, as though to reveal its hidden layers in a surrealist geological diagram. A number of genial-looking fish, all floating horizontally, have swallowed a few human beings whole. From the mouth of one, half a naked body protrudes: a bearded red-haired man emerging from a monstrous black fish holds out his hands to a single hand outstretched piteously from the top of a red octopus. The beautiful head of a woman pops out of the mouth of a red fish, and she looks serene in her captivity. A foot here and a leg there have yet to be swallowed. Above the lake, at ground level, figures of Christ illustrate different Gospel episodes by a row of tower-like buildings. Above them, in heaven, presumably, are groups of three and four, prophets or priests or saints, encircled by garlands of cottony clouds. The humans being swallowed by fish, a depiction of hell, reminded me of The Garden of Earthly Delights by a contemporary and follower of Hieronymus Bosch, which was painted in circa 1515. “It is no accident that the first Armenian book was printed in Venice in 1512,” Evans told me, “and that in the same sixteenth-century Armenian colonies flourished from Amsterdam to Madras, from the Crimea to Ethiopia.” Armenians have settled pretty much in every region of the world, and they have done so since antiquity, though the modern, and most tragic, Armenian diaspora was a result of the 1915 mass deportations and genocide.

Armenia is a country so often moved from one physical location to another that it has become adept at conjuring up its prophets and angels more easily than its landmarks. Listen to the legendary Komitas Vardapet (1869–1935) here singing Armenian liturgical music. His quivering voice occasionally goes off into a disquieting, almost rasping sound, as though migrating to a new land—the immaterial Armenia of faith and memory.

Armenia! is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 13.