The story of British novelist Penelope Mortimer is, in part, the all too familiar tale of a woman writer plagued by her readership’s inability to separate the life from the art. This situation was made all the more complicated because Penelope drew so very heavily on her lived experience when it came to the fiction she put down on the page. As debates around this issue still rage today, despite the fact that Penelope’s books, published between 1947 and 1993—nine novels, a short story collection, two volumes of memoir, and a biography of the Queen Mother—languish for the most part out of print, there’s no better time for readers to discover both the fascinating story of her life, and her once highly acclaimed writing.

In the late 1950s and the early 1960s, the Mortimers—John and Penelope, and their six children—proved irresistible to the press. As was observed in the double profile of the husband and wife that ran in the regular “Personality of the Month” column in the October 1958 edition of Books and Bookman magazine, the Mortimers “are not just literary personalities. Their large and happy-looking family are frequently photographed and have received attention from both the popular and the more sober representatives of the press.” Fittingly, the accompanying photograph shows the couple surrounded by five of their six children. John combined his esteemed position as a barrister with an increasingly high-profile writing career, producing hit novels, plays, and film scripts, as well as short stories, reviews, and a weekly column (under the pen name Geoffrey Lincoln) about life at the Bar for Punch. His home life with his beautiful, talented novelist wife, and their brood of children, was seen as equally enviable. In the double-page spread featured in the 1960 Christmas issue of Good Housekeeping magazine, John and Penelope describe the festive holiday traditions in their home. As the piece points out, the Mortimers are not the “usual” family. In addition to writing novels, and journalism for The Observer, and The Sunday Times, Penelope was a regular fiction contributor to a variety of magazines from Lilliput to The New Yorker.

One of the stories she published during this period was “Such a Super Evening,” which appeared in the former in 1959. It’s narrated by an unassuming housewife who can’t believe her luck when a famous couple accept her invitation to dinner. Nothing short of “an institution,” the fictional Mathiesons “symbolize a whole way of life.” They’re the parents of eight “remarkable” children, but they’re also both “fantastically successful writers,” full of energy, humor, and intelligence. “None of the stories could accurately be described as fiction,” Penelope later explained, making no secret of the fact that she “mined” her life for ideas; “the moment I fabricated or attempted to get away from direct experience The New Yorker regretfully turned it down.” But “Such a Super Evening” is not a case of shameless bragging. As the night progresses, the gleam of the Mathiesons’ glamour is tarnished, and their apparently perfect marriage is exposed as anything but. He reveals that his wife’s famous energy comes courtesy of “American pills,” while she’s quick to disabuse the fawning company of her husband’s commitment to either work or family. Rather than revel in everyone’s admiration of his children, Mr. Mathieson boasts about how he uses them in a tax evasion scheme before confessing that not all of them are his anyway, at which point Mrs. Mathieson erupts in violent hysterics. The story is a scathing satire of Penelope’s own family. Admittedly, the more egregious abuses here are the figments of the author’s imagination, but a kernel of truth underlies the story: her and John’s marriage was far from as perfect as it looked to the outside world.

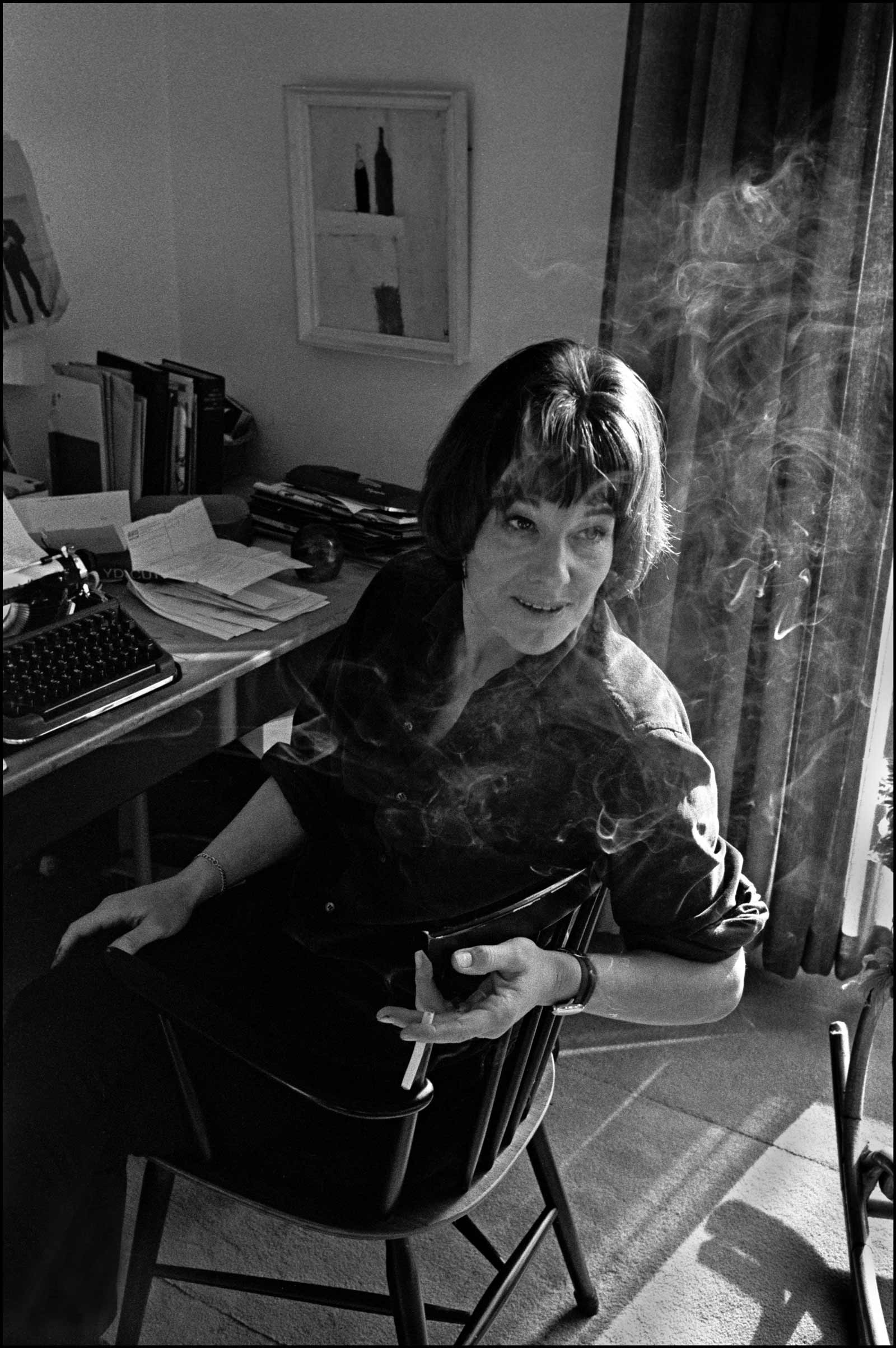

What the many profiles and accompanying photo shoots of the famous Mortimer family didn’t show was the overdose Penelope had taken in early 1956, or the affairs John was having and would continue to conduct through the end of their marriage in 1971. They don’t portray Penelope’s own dependence on pills, her unhappy visits to a psychiatrist, or her frustrations with the demands of domesticity. The all but forced abortion and sterilization she underwent in the spring of 1961 is hard to reconcile with the photos of this picture perfect family that precede it, especially the striking portrait of the couple that ran in The Tatler in 1961, in which, against the backdrop of an elegant-looking bookshelf-lined room, the beautiful Penelope sits at her desk, cigarette in hand, gazing beatifically up at John who’s resting his right hand on her typewriter. When she put pen to paper only ten months later in November 1961 to write what would be her most successful novel, The Pumpkin Eater (republished in 2011 by New York Review Books), about a housewife’s breakdown following the collapse of her marriage—she finds herself suddenly and without warning openly weeping in the Harrods linen department, “sprinkling the stiff cloths with extraordinarily large tears”—it was a depiction of familial disharmony that was revolutionary for its time. Thereafter, Penelope’s writing was an ongoing attempt to construct a self that society continually denied her. She spent the remaining thirty-eight years of her life trying to carve out a public identity that matched how she felt in private, but ultimately it was to no avail. She was trapped as Mrs. Mortimer, mother of six and the wife—then ex-wife—of the more famous John.

Advertisement

*

Penelope Fletcher married her first husband, the Reuters correspondent Charles Dimont, when she was nineteen years old. By the time she met John Mortimer ten years later, she was already the mother of three daughters, with another on the way—her eldest two had been fathered by Dimont, her third by Kenneth Harrison, and her fourth by the poet Randall Swingler, who, on finding out she was pregnant, disappeared from her life for the next seventeen years. She and John were married on August 27, 1949—the day her divorce from Dimont came through—and went on to have two more children, another girl and a boy. Although Penelope had been writing for years—her first novel, Johanna (published under the name Penelope Dimont), appeared the same year as John’s debut, Charade—wife and mother were the identities that publicly defined her throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s. She wrote a column, “Five Girls and a Boy,” for the Evening Standard which proffered advice on topics like choosing schools or organizing birthday parties.

Meanwhile, after signing a contract with The New Yorker in 1957 for six stories a year, she also provided the magazine with a “steady stream” of writing inspired by daily domestic life. She published three novels before the decade was out—A Villa in Summer (1954), The Bright Prison (1956), and Daddy’s Gone A-Hunting (1958)—as well as co-authored, with John, an account of an Italian summer sojourn en famille, With Love & Lizards (1957). To many, it appeared that Penelope had achieved the enviable work-life balance many women today are still striving for. Behind the scenes, however, things were beginning to come apart. One only needs to look to her short story, “Saturday Lunch with the Brownings,” published in The New Yorker in 1958, to catch a glimpse of the tensions that lay beneath the surface. A put-upon wife and mother, Madge Browning, struggles to appease her husband William as he’s increasingly vexed by their house full of children distracting him from his work and generally getting on his nerves. “What’s the plan?” he demands of Madge as they lie in bed together first thing in the morning. “He meant, she knew, what had she arranged for them today, this compulsory holiday; what had she provided for their entertainment, what meals, expedition, security from disturbance.” Not only does the story speak to the unfair division of labor in the home—what had she arranged to keep the children out of his hair—it also highlights another inequality: between the way William treats his biological daughter Bessie, “his darling,” whom he spoils, and her step-sisters, Madge’s daughters Melissa and Rachel, with whom he’s much less tolerant. Despite the differences between characters, circumstances and settings, like “Such a Super Evening” the year before, “Saturday Lunch with the Brownings” revealed something of the reality behind the Mortimer façade:

If we can just get through lunch, Madge thought, we shall be all right. She beamed at him encouragingly as he picked up the carving knife and fork. It was at times like this, when they were all together and relatively peaceful, that she almost felt they might make a success of it. She had given William roots, set him at the head of a family table, given him something to work for; she had given her own children a home and a father. The picture was as clear, as static and lifeless as a Victorian print of domestic bliss. It was her ideal, doggedly worked for. That, she had told herself, the strong, wise, loving father, is William; those devoted, secure, happy children are ours; that beautiful, gentle, capable mother might, with a stretch of the imagination, be me. This is Saturday Lunch with the Brownings.

Of course, such bliss is short-lived, and by the end of the meal, the family are fighting again. Despite Madge’s rule of never arguing with William in front of the children, she explodes in fury. “You think I’d stay with you and these delinquent little bitches of yours?” William shouts in retaliation. “Get their father to keep them. Go on, go and find him. Tell him to keep the lot of you on his five pounds a week. I’m taking Bessie and I’m getting out.” As Valerie Grove perceptively observes in her biography of John, A Voyage Round John Mortimer (2007), “Penelope did more than milk their domestic life; her stories reflect how deeply and sympathetically she understood her children and how she also felt a fundamental empathy with her beleaguered, over-burdened husband.”

Advertisement

But these weren’t the only issues putting a strain on the Mortimers. From the mid-1950s onward, John embarked on a series of inconsequential, albeit damaging affairs, so it’s no surprise that the subject of marital infidelity preoccupied his wife’s novels during these years. While her tackling of the subject was judged masterful in A Villa in Summer, one critic describing it as “a brilliantly successful attack on one of the most challenging fortresses of fiction: the spiritual and physical relationship of married life,” The Bright Prison was deemed notably less effective. The novel, set over the course of a single weekend in the depths of winter when a couple’s marriage comes under pressure and their family’s life breaks apart, clearly draws on the “black, black time” Penelope describes in her diary:

House in chaos, children rampant; everything wrong. I am enquired into until I feel desperate, hysterical; Pen, Pen, PEN, all the time. And days of bad temper & bad liver & childishness sandwiched between nights which are meant—god knows how—to transform me into a devoted angel. I can hardly stand it, the perpetual personal prying: what are you thinking, feeling, doing, & why? And not a thought or an idea or even a laugh in between it all. Stale. Everything, in this hot & dusty room, stale and over-breathed & under-nourished. During the days, I’ve been working from 10.30 to 3.30; then, after the children are fed & fetched & put to bed, I’ve made a dress for Sally and a coat for Julia. I am sucked dry like the lemon and could scream with this Pen Pen PEN—in fact do scream, which helps nothing.

All the vicissitudes of marriage and motherhood—the confusing contradictions of loving one’s children and finding much of one’s meaning in life as a mother, but so, too, feeling trapped by motherhood itself, and longing to be viewed as something more than a caregiver—culminated for Mortimer in 1961. In February, she discovered she was pregnant for the eighth time (two years earlier a seventh pregnancy had ended in miscarriage). The forty-two-year-old mother of six—her eldest was twenty-three, her youngest only six—was suffering from depression, and her marriage was on rocky ground.

Although she initially embraced the idea of having another child—her short story collection, Saturday Lunch With the Brownings, had been published to tepid reviews the year before (one rather hostile review described the couples in the stories therein as “trivially embittered, chronically quarreling about nothing, filled with a fatigued desperation”), and she thought a new baby might bring her the contentment her writing hadn’t—both her doctor and John encouraged her to have a termination; the former advice on medical grounds, the latter arguing that saving their marriage mattered more. Putting her faith in John, Penelope agreed to both an abortion and sterilization. But while recovering from the surgery in the hospital, the wound in her abdomen still a “suppurating mess,” she discovered that John had been having yet another affair (with the actor Wendy Craig whom herself soon became pregnant, bearing him a son) since the beginning of her pregnancy. The news was devastating.

After a lengthy, near unbearable period of writer’s block, Penelope began work on The Pumpkin Eater that November. She poured her recent experience into it, barely fictionalized, and the writing came naturally: “like being oiled, shining, on ball-bearings once more,” she wrote in her diary. “I went to the basin and was sick,” says Mrs. Armitage, the protagonist, when she discovers that her husband Jake, a very successful writer, advocated for her surgeries because a new baby would have forced him to end the affair he was having. “I could feel the lips of my wound parting, as though my wound were laughing at me.”

Published the following year, The Pumpkin Eater is as close to autobiography as a novel can be while still professing to be fiction. It’s a book that resounds with truth—both Mortimer’s own and that of many women of the era. Shortly before Mrs. Armitage has her abortion, she receives a letter from a Mrs. Evans, who explains that she was prompted to put pen to paper after seeing a photo shoot of the supposedly happy Armitage family in a magazine. Mrs. Evans is married, with three children, and has recently had a hysterectomy, she explains. She toils from morning to night cleaning and cooking, but there’s never enough money and, to add insult to injury, her husband refuses to make love to her anymore. “Please write to me before I do something I’ll regret,” she begs Mrs. Armitage, “because my love for the babies won’t hold me here if things don’t change.” Conscious that the photograph that elicited Mrs. Evans’ letter didn’t tell the full story, Mrs. Armitage struggles to think of how to reply:

‘Dear Mrs Evans, I enclose a cheque for £10. This, of course, is tax free and therefore worth double…’ ‘Dear Mrs Evans, I am about to have an abortion and wonder if you could give me some advice…’…. Dear Mrs Evans, my friend. Dear Mrs Evans, for God’s sake come and teach me how to live. It’s not that I’ve forgotten. It’s that I never knew…. Really, anyone would think that the emancipation of women had never happened.

Penelope’s diary from the mid-1950s is full of tirades against a woman’s lot—“My life has been measured out in meals, socks, little bloody Noddy,” she wrote only six weeks before starting The Pumpkin Eater—and outrage at the fact that few told the “ridiculous truth” about motherhood and domesticity. Seven years later, she did just that. “[A]lmost every woman I can think of will want to read this book,” wrote Edna O’Brien, then just enjoying her meteoric rise as a fiction writer who brought a new realism to the lives of young women on the page, of Penelope’s magnificent novel when it was published. Meanwhile, on the other side of the pond the reviews were equally euphoric: “a subtle, fascinating, unhackneyed novel,” wrote the feminist author and critic Elizabeth Janeway in the New York Times. “Mrs Mortimer is toughminded, in touch with human realities and frailties, unsentimental and amused. Her prose is deft and precise. A fine book, and one to be greatly enjoyed.” Not that Penelope could enjoy these glowing write-ups—she was recovering from the overdose she had taken at the beginning of September, and the subsequent hospitalization and ECT treatment she underwent.

Somewhat tragically, while The Pumpkin Eater cemented her professional reputation, it did little to free her from the bonds of domesticity; it simply made her famous for writing about them—it remains the best-known of her books. In early 1962, despite naming Penelope as one of the “Top Women in literature today,” the feminist writer and critic Elizabeth Coxhead also complained about her—and other contemporary women writers’—narrow outlook. “[I]t is curious,” she writes, “that though life offers a woman so much more scope than it did in George Eliot’s day, none of these writers have her breadth of interest. They keep mainly in the world of acute sensibility, whose most noteable [sic] explorer was Mrs. Virginia Woolf.” Coxhead elaborates on her observations in Books and Bookmen magazine:

It would be unfair to say that they [Coxhead names Penelope, alongside Rosamond Lehmann, Elizabeth Taylor, and Elizabeth Jane Howard] have only one theme; but the anguish of love betrayed so haunts them that it eclipses all the rest. Reading them, you would never know there had been a movement of women’s emancipation—and indeed, for the young married woman of the middle classes, there hasn’t. She is the one to whom our society has given a thoroughly dirty deal, by shutting her up in a suburban house or flat with a family of small children and a lot of gadgets, and no intellectual outlet—except, of course, to write novels.

*

Penelope and John struggled on together for the next decade before eventually divorcing. The novels she published during these years are both attempts to make sense of the aftermath of the conflicts portrayed in The Pumpkin Eater and efforts to reinvent her identity without John by her side. Her 1971 novel The Home is The Pumpkin Eater’s sequel in all but name. “[A]lone, untrammelled, a free human being,” for the first time in her life, Penelope’s heroine—another surrogate for Penelope herself—Eleanor Strathearn is starting over again after twenty-six years of marriage. She’s “rediscovered energy that she thought had long ago died,” but harnessing this in the service of a future proves nearly impossible.

Later, in her diaries Penelope described herself as a “Handicapped Parent” during these years. “[My children] longed for me to grow up, leave home, have a successful job, get married. But I couldn’t.” Much of this, she understood, was gendered. “If I were a man I’d take on or marry a young wife; possibly have children; sit in my study and work away while life went on round me, always on tap.” She didn’t need to mention John by name; it’s clear she was thinking about the freedoms society afforded him and denied to her. He didn’t find it hard to reinvent himself either professionally or personally after their divorce. He immediately went on to build a new life with the woman who later became his second wife and bore him two more daughters, yet “husband” and “father” were not identities that ever limited him. On the contrary, he enjoyed kudos for his conquests; he was often described, with shades of admiration, as a famous “womanizer.” By comparison, Penelope’s efforts to make sense of the woman she was now—no longer a wife, nor a mother able to bear any more children—was made even harder because of the public’s inability to separate the writer from her writing. Punishment particular to a woman.

In October 1972, doctors advised Penelope that she needed a hysterectomy. “Once…there was a young man called John Mortimer,” she writes melancholically in her diary. “Now it’s lawyers & hysterectomies & John Mortimer distant, tiny, remote, gesticulating at the wrong end of a Fallopian tube.” She has the operation in January 1973, and, like her sterilization twelve years earlier, it plunges her into another deep depression. But history repeated itself in more ways than one. Just as her breakdown in 1961 bore creative fruit in the form of The Pumpkin Eater, this time around she produced Long Distance (1974), which she considered “the most important achievement of my career.” Written that summer of 1973, during a residency at Yaddo, it’s a continuation of her autobiographical project, although the novel doesn’t adhere to the traditional mimetic qualities of her previous works. Instead, it’s a fragmentary and hallucinatory account of her unnamed protagonist’s desperate journey through an unspecified institution—part Yaddo, part hospital—that clearly draws on Penelope’s experiences of being hospitalized for depression. Her narrator is “a blank slate, an empty glass,” someone who’s doomed to “repeat experience until it is remembered.” So, too, does the novel’s narrative loop back on itself, dream and reality converging, past and present overlapping, and the narrator experiences her fragmented sense of self as a physical splitting.

Without doubt, it’s Penelope’s boldest bid to start over, both as a woman and as a writer. As the critic Ronald Blyth noted, “The sexual and spiritual progress of female middle age has rarely received such an excitingly imaginative treatment.” And while it was published in The New Yorker in its entirety, something the magazine hadn’t done since J.D. Salinger’s Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters in 1955, the novel failed to have the impact Penelope hoped. The figure of the broken housewife was one the public could rally around. That of the middle-aged divorcee battling her demons in order to secure for herself a fresh start apparently, less so.

*

“I have to go on from LONG DISTANCE,” Penelope wrote in her diary four years after the book was published. “That ‘body’ of domestic novels isn’t enough.” She was all too aware of the fate of the authoress whose work is maligned, dismissed as inward-looking and unimportant. Later that year, she left London and moved to a hamlet in the Cotswolds, which provided her with the setting for her ninth and final novel, The Handyman (1983). “She no longer knew what her role was,” Penelope wrote of Phyllis Muspratt, her middle-aged protagonist who buys a country cottage following her husband’s death, “pulled this way and that, protected and unprotected, assumed to be dependent on those who ought to depend on her and independent by those who didn’t know how to treat her as a solitary woman.” Reflecting her own battle for self-realization, the figure of the solitary woman would preoccupy Penelope for the final two decades of her life.

Two unfinished, unpublished novels haunted her during this time. The first she began almost immediately after her divorce, describing it as “a swan song, a huge, rambling story told by a grossly fat old woman I called Agatha. Everything I had ever thought, felt or experienced would go into Agatha, except that there would be no children. In this way I might discover the person I was before I married […] the person I needed now my tenuous thread with the future was broken.” If Agatha was driven by Penelope’s desire to rediscover the woman she had been before three decades of marriage and motherhood left their indelible imprints on her identity and body, the other work in progress that increasingly consumed her attention—a grand novelistic retelling of King Lear which replaced the domineering father figure with a formidable matriarch—was tied up in Penelope’s attempts to make sense of the lonely future she found herself facing.

Lear is also a project that sheds light on the biography of the Queen Mother that Penelope published in 1986. Considering her royal subject in a very particular context—a woman who had been a constitutionally enshrined, living embodiment of widowhood for over thirty years, her very title implying “the lonely eminence of a widow, a solitary female relic of the previous reign”—allows us to see the book as something other than the puzzling aberration in Penelope’s canon that it’s been all too readily dismissed as. The Queen Mother was fifty-two years old when she was widowed, only a year younger than Penelope when she and John divorced. By the time Penelope came to write this biography, she had had more than a decade of first-hand experience feeling like the “solitary female relic” of what had once been widely promoted as her and John’s glorious reign. And while the intervening years had only seen John become more and more famous, Penelope’s prominence was steadily dwindling.

*

Contrary to the impression I might have given here, Penelope lived an extremely interesting life in the years following her divorce from John. Throughout the 1970s, she split her time between the UK and America. There were her two residencies at Yaddo—during the first she wrote Long Distance; while she used the second, five years later in 1978, to write her first memoir, About Time: An Aspect of Autobiography (1979), which went on to win the prestigious Whitbread Prize—as well as periods spent teaching, at The New School and Boston University. She also made a great many interesting friends in America: Penelope Gilliatt, The New Yorker’s film reviewer; Kurt Vonnegut; Edmund White; and the film star Bette Davis among them—her encounters with the latter, as described in Penelope’s second memoir, About Time Too (1993), are nothing short of fabulous (on settling Penelope into a cottage the actor had rented for the writer, Penelope writes how Davis “showed me how the dishwasher worked, broke a number of plates, swore a great deal, prepared me a supper of southern fried chicken, told several scurrilous stories about Joan Crawford and finally left.”)

However, despite personal and professional successes, Penelope continued to be stalked by depression, along with a gnawing sense that she hadn’t achieved what she should have. She felt stifled by the woman she’d once been, Mrs. John Mortimer, mother of six, author of The Pumpkin Eater, a novel that although still admired was fading into relative obscurity with every passing year. Although The Pumpkin Eater had resonated so poignantly with O’Brien, the Irish writer was twelve years younger than Mortimer, and that age gap, slight as it was, made all the difference. O’Brien’s rebellious voice may have resulted in the banning of her fiction in her homeland of Ireland, but it won her acclaim in England and thereafter in America too. Her debut, The Country Girls (1960) kicked off the decade of the sexual revolution and women’s liberation. When Penelope had published her first novel thirteen years earlier in 1947, the world had been a very different place, and she found herself still trying to fight her way out of the sexual stereotypes of the 1950s—the decade during which she came of age both as a writer, and a woman—long after she’d left those years behind.

Her story is also a lesson in the damaging effects of the term “woman writer,” and the many inequalities stemming from the association. When Penelope died in 1999, the legacy that remained was the same one she’d spent the previous four decades trying to escape. As she put it in her last book, About Time Too, which was published only six years before her death: “The outside world identified me as ‘ex-wife of John Mortimer, mother of six, author of The Pumpkin Eater’ [in that order]—accurate as far as it went, but to me unrecognisable.”