National artistic vanguards tend to come in two types. Some groups, like the revolutionary muralists in Mexico, consciously set out to depict an aspect of their country: its people, its landscape, its culture. Others, like the American Abstract Expressionists, develop a novel style or approach, make an aesthetic breakthrough, which only later comes to be associated with the country of its origin.

Over seventy years after its founding, it remains unclear whether India’s Progressive Artists’ Group (1947–1953) is a national vanguard of the first or second type. Art historians like to peg them as a band of dyed-in-the-wool regionalists, and the Bombay-based collective is commonly identified as the prime mover of a rooted and authentic Indian modernism. From time to time, PAG’s members—the “Progressives,” as they are now called—even made remarks to this effect. One of the founders, S.H. Raza, insisted late in life that the group’s goal was to articulate “an Indian vision and Indian ethnography.”

Yet, other Progressives disavowed all political, let alone national, readings of their work. “Today we paint with absolute freedom for contents and techniques, almost anarchic,” F.N. Souza, PAG’s leader and impresario, put it, in a pungent opening manifesto. “At no stage did the whole business of nationalism come into it,” Krishen Khanna, a younger member, maintained decades later. “None of us wanted to be known as Indian painters.” In this telling, the group is to be remembered for its formal achievement, which essentially boils down to combining Western innovations (mainly Expressionism and abstraction) with the techniques of older Indian art.

Of course, the two accounts are not mutually exclusive. Souza memorably grappled with the issue of indigeneity in his paintings (in his essays, too) and Khanna pictured the day’s big political issues in canvas after canvas. If they distanced themselves from the ideology of “Indian-ness,” it’s probably because they found its rhetoric somehow limiting or off the mark. An ambitious new exhibition at the Asia Society Museum, “The Progressive Revolution: Modern Art for a New India,” allows us to revisit their legacy, and consider the ways they did or did not engage with nationalist thinking.

*

Curators Zehra Jumabhoy, a professor at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, and Boon Hui Tan, the director of the Asia Society Museum, have organized some eighty works, mainly paintings, across three sections. The first, “The Shock of the New,” serves as an introduction to the Progressives. The second, “The People of the New India,” presents overtly political paintings. The third, “National/International,” is a showcase of the group’s formally innovative work. In this way, the second and third sections compete with one another, neatly falling on either side of the vanguard question, one foregrounding content, the other form. Viewers have to decide which answer holds up better. (There is also a brief coda titled “Masters of the Game,” which gathers the greatest hits, or some of them, at any rate.)

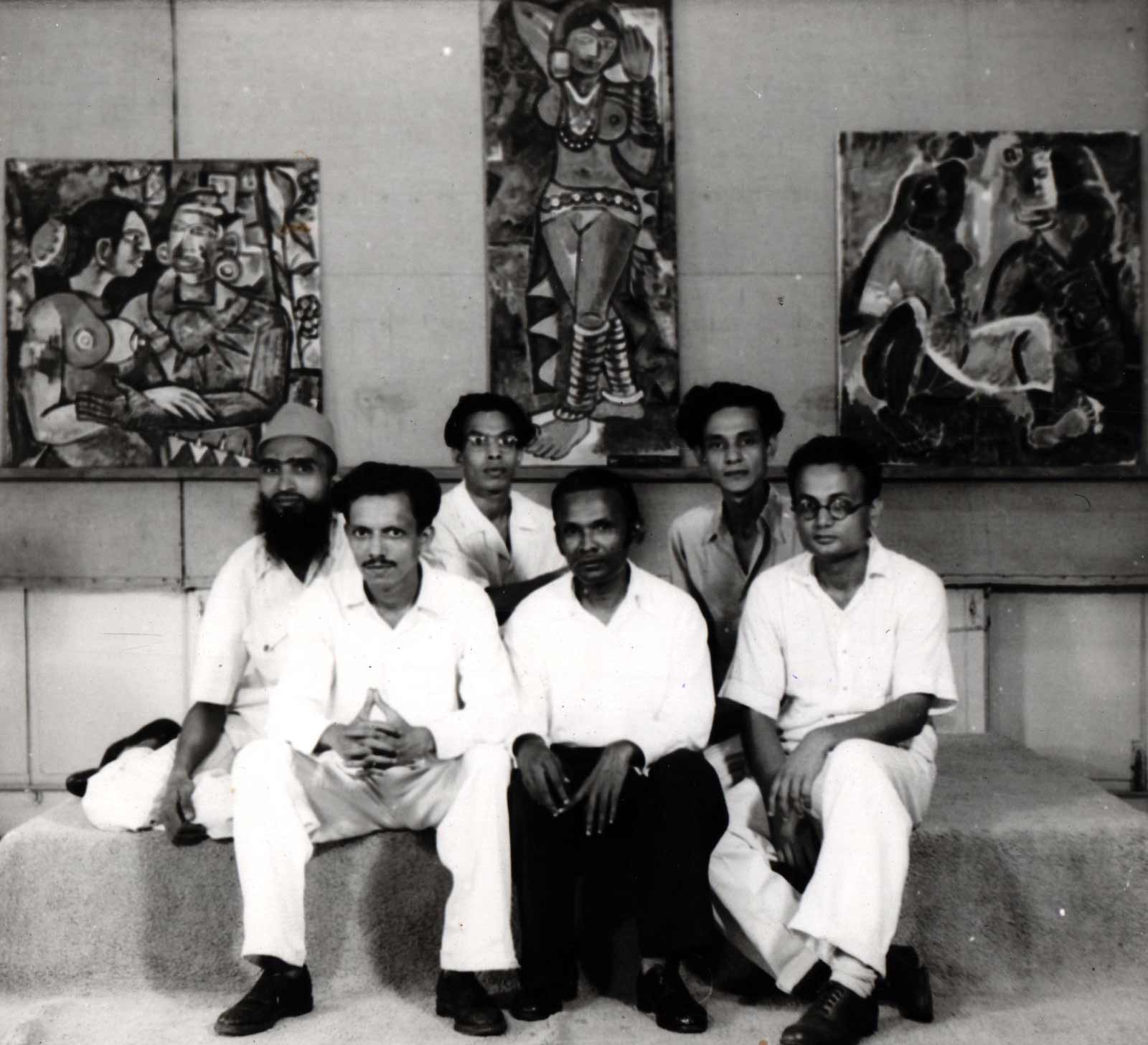

“The Shock of the New” is a recreation of the Progressives’ first major show in 1949, in which the founding six members—Souza, Raza, M.F. Husain, K.H. Ara, H.A. Gade, and S.K. Bakre (the group’s sculptor)—displayed their best early work. It wonderfully captures the excitement of the period, when old conventions were cast aside and new approaches sought out.

In the mid-1940s, there were two reigning schools of art in India, mutually opposed and equally dour. Colonial art institutes promoted a watered-down version of academic naturalism; and the so-called Bengal school, which grew out of the nationalist movement, championed a kind of Orientalist revivalism (Hindu goddesses, timeless village pastorals, and so forth). The Progressives rejected both these approaches, and did so with impudence. “We have no pretensions of making vapid revivals of any school or movement in art,” Souza wrote in his manifesto.

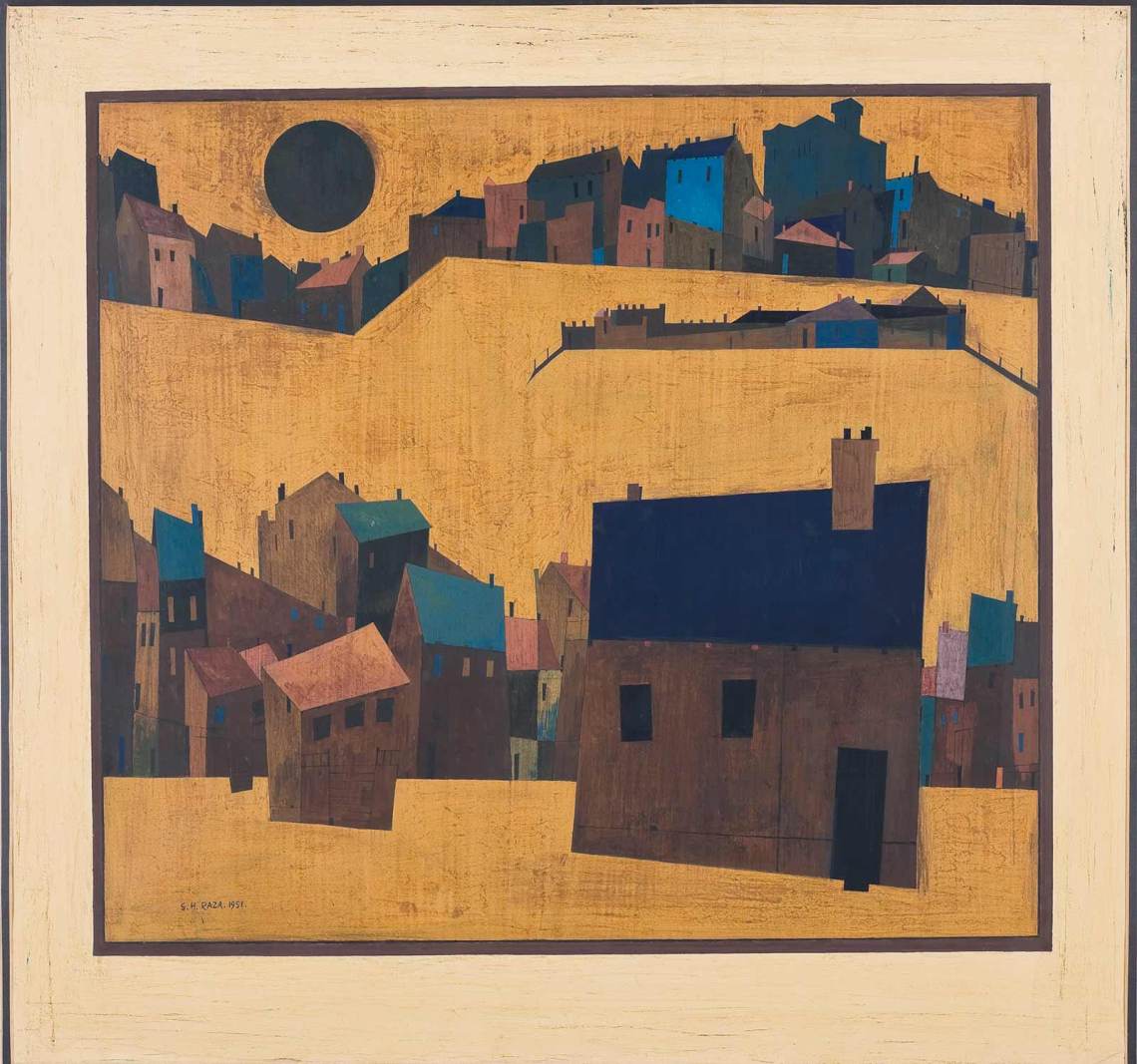

Instead, they looked to advanced European painting, introduced to them by Walter Langhammer and Rudolf von Leyden, Austrian refugees who mentored the group and championed them in the press (von Leyden was the first art director of The Times of India). The Progressives’ early work shows traces of Expressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, and even Primitivism—none of it fully digested and much of it put to strange ends.

Consider Souza’s nude Self-Portrait (1949), a complex and somewhat baffling painting. On the one hand, it is a catalog of deformities. The artist’s painfully bony, boyish figure has been wildly modeled, with uneven kneecaps and mismatched nipples, a crooked shoulder and club foot; and he’s covered in a mix of garish and brooding colors, which here and there seem to give way to a gangrenous soot. Yet this is counterposed by his dignified and vulnerable expression, not to mention his firm, exaggeratedly strong hands, which would seem to belong to a much larger, more virile man (tellingly, the distortion extends to his paintbrush).

Advertisement

In a sense, Souza has depicted himself as a colonial Gauguin: part squalid savage, part refined aesthete. Another artist (Gaugin himself, say) might have reduced this contrast to melodrama, but there is something authentically naïve (some might say tasteless) about Souza’s painting—after all these decades, it retains its power to shock. In an art historical sense, it’s also an important marker. Art before the Progressives was tepid and impersonal. Here, for the first time, the painter is taking center stage.

*

“The People of the New India” gathers paintings that, in one way or another, depict post-independence Indian society. This is a challenging and basically miserable subject, with little room for upliftment, as viewers of Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak’s films can attest. Postcolonial boosterism aside, the Indian National Congress’s scorecard makes for dismal reading. Despite its iron grip on power—it won all the elections through 1977—Nehru’s party failed to effectively raise food production or develop industry (though the former imperial power Britain can partly be blamed for this), combat the country’s entrenched, grotesque inequality (less excuse here), or reform the ancient barbarism of social caste (absolutely no excuse here). It’s not for nothing that Ghatak called independence the “great betrayal.”

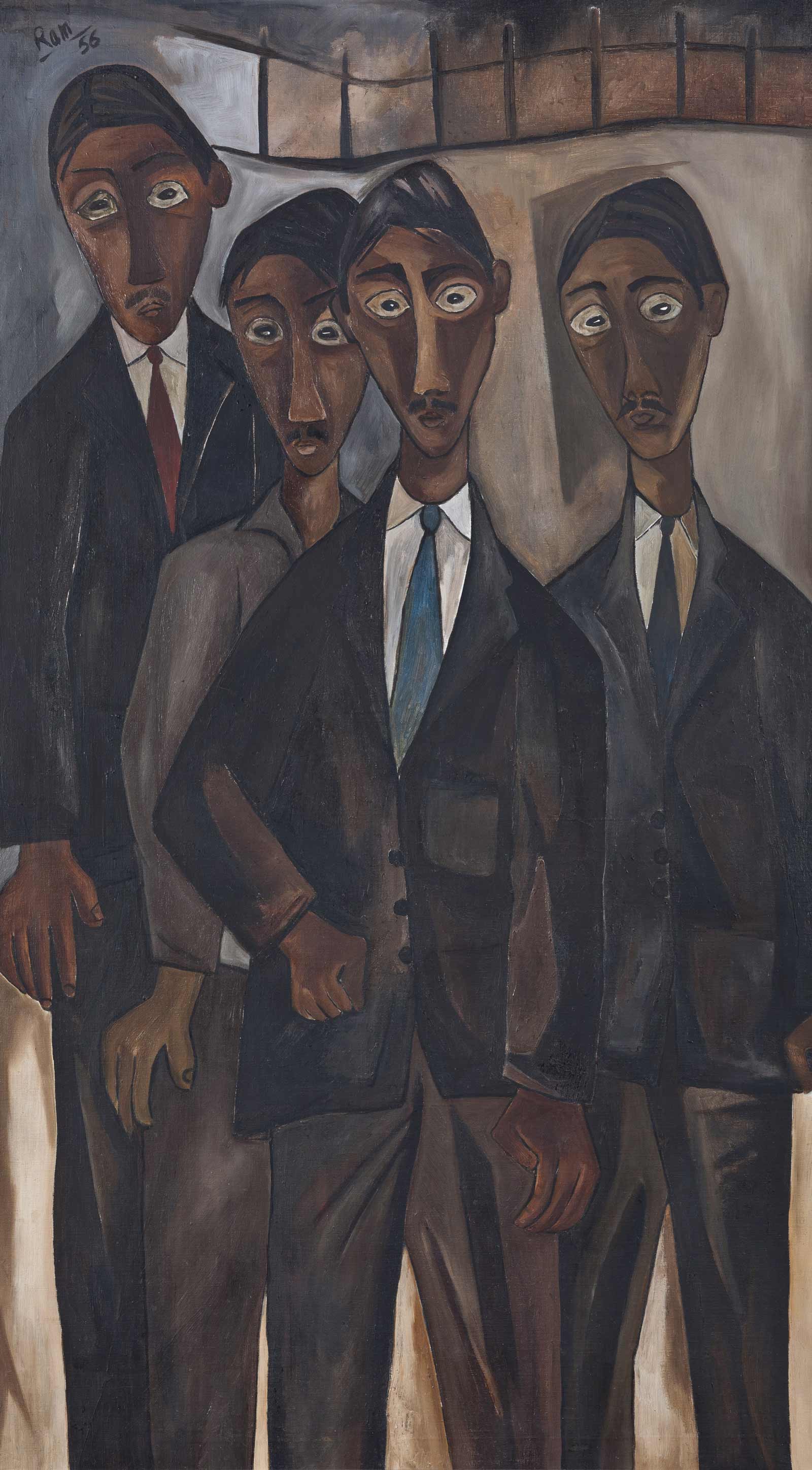

But you guess none of this from the evidence of the paintings in this section. There are two works that might be described, with a modicum of good will, as examples of probing social realism: Ram Kumar’s Unemployed Graduates (1956), an evocative if somewhat self-pitying depiction of middle-class penury; and Souza’s Grosz-esque Tycoon and the Tramp (1955). But the rest of these ostensibly socially conscious paintings are variously calm, cheery, buoyant, even idyllic. It’s as if they were painted in order to keep the artist’s hopes up.

The curators frame this as a kind of aesthetic idealism. They argue that the Progressives were depicting the two main national ideologies of the era: Gandhi’s vision of a “folk” nation rooted in its villages and Nehru’s creative theory that a country was strengthened rather than weakened by its dizzying ethnic and religious differences. Given India’s current political set-up—Prime Minister Narendra Modi is an inspiration for Islamophobes around the world—it’s unsurprising that Jumabhoy gives extended play to the second idea. “It is important to notice [that] their visual language was deliberately constructed to make a case for a secular India,” she writes in her catalogue essay. “The Progressives… made a case for a plural nation, providing a visual counterpoint to Nehru’s plea for ‘unity in diversity.’”

A painting by Krishen Khanna best illustrates her point. News of Gandhiji’s Death (1948) is a tableau of ten people reading about the great man’s assassination in the evening paper (the figures are organized around a streetlamp). It certainly offers a diverse cross-section of society, with one man wearing a Muslim Kufi, another a Sikh turban, a woman in a traditional Hindu sari, and so on. But it’s precisely these labored details that point to a fundamental imaginative failure. The characters, rendered in a flimsy, illustrative style, amount to little more than their clothing: they are Indian “types,” not fully realized fellow citizens—compare the Mexicans in the works of Orozco or Rivera—and they have the appearance of being tacked onto the frame like butterfly specimens.

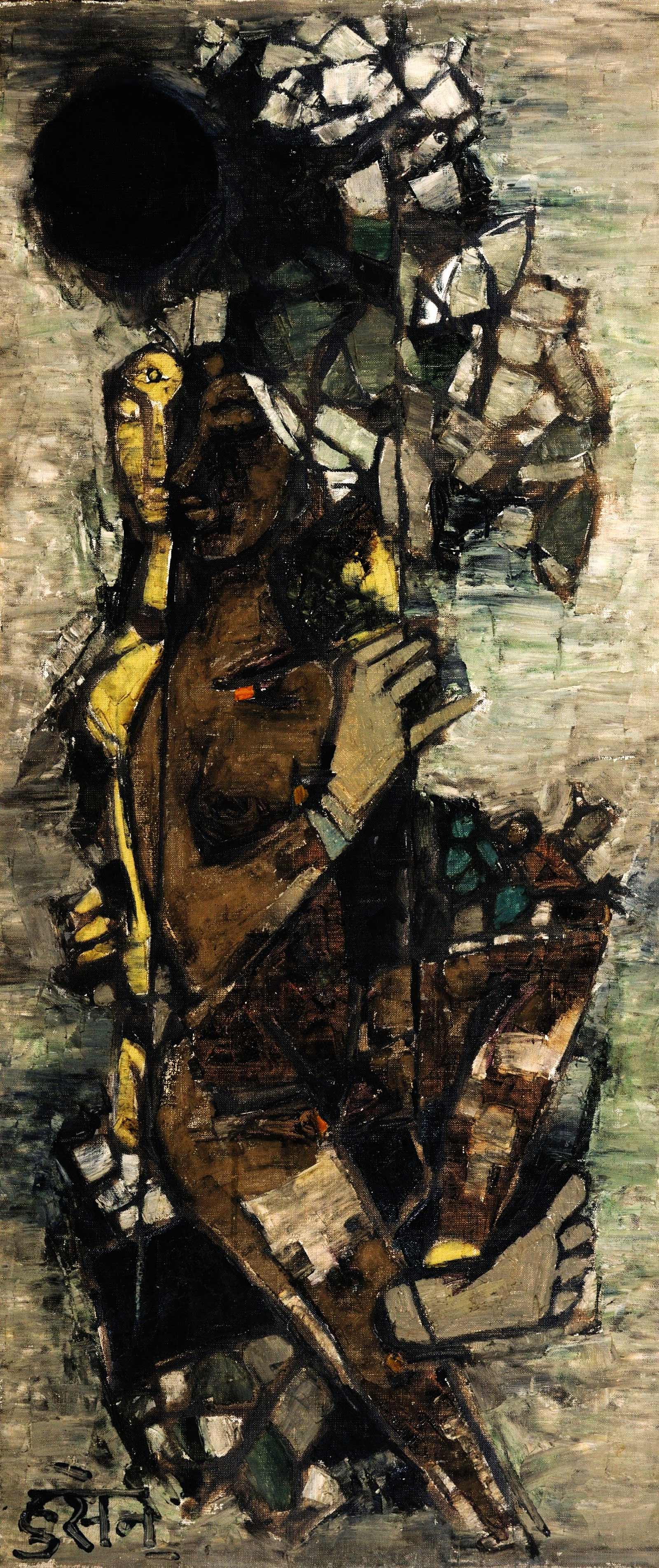

Khanna’s painting points toward a larger problem. The nationalism of the Congress, in both its Gandhian and Nehruvian variations, was sustained by volk-ish fantasies of the most feeble, retrograde sort. As social artists, the Progressives might have pictured the country’s real divisions and contradictions; instead, they toed the party line, and even sought forms (the frieze, the tableau) compliant to its agenda. It’s no surprise that the paintings in this section—by Khanna, Souza, Ara, and, especially, Husain—seem dull and hokey. If, pace Raza, this was “an Indian vision and Indian ethnography,” then one must conclude that it lacked clarity and included few real people.

*

“National/International” is the other thematic section. Here, the curators place the Progressives at the intersection of Western and Asian aesthetic traditions, drawing all kinds of connections (some more creative than others) between their paintings and older artforms from the Indian continent. Wall text is their primary weapon—and some of it is bludgeoning—but Jumabhoy and Tan have also staged an intervention. With old-fashioned Orientalist confidence, they have worked their way through the museum’s permanent collection, selecting a few medieval and ancient works of Asian art that visually rhyme with the Progressives’ paintings. These have been placed in “suggestive” positions throughout the gallery (there are one or two in the earlier sections as well), as if to establish a mystical connection between the moderns and their ancestors.

The actual story is, of course, more modest and straightforward. The Progressives looked keenly but unpiously at older Indian artforms, taking what they liked and updating it for their own ends. Two paintings in this section nicely bracket the wide range of approaches. Akbar Padamsee’s Lovers (1952) is a marvelously serene depiction of a nude couple sitting on a bull. The animal is traditionally associated with the god Shiva; not too subtly, the curators have placed the painting beside a tenth-century sculpture of Shiva and Parvati. But Padamsee is not concerned with this subject matter, at least not in such a literal way. It is the strange mixture of robust sensuality (rounded limbs, tender digits) and innocence (the faraway expression, a total lack of tension) that relates his figures to older Indian sculptures of divinity.

In Temple Dancer (1957), Souza combines the languid figuration of a Chola or Pala sculpture and the stern moralism of Rouault with a sexual hysteria that is all his own. The result is a ferociously lewd picture, in which the female figure is both insatiable sex goddess and innocent child (this, we know from his interviews and published essays, is more or less how he imagined women). “Akbar handles the sacred rather than the profane aspect of the image, whereas Souza has done exactly the opposite, taking up religious subjects for the express purpose of committing sacrilege,” the critic Geeta Kapur concluded in her seminal study, Contemporary Indian Artists (1978).

The exhibition would have benefited from more paintings pitched at this level. Alas, the curators have selected too many pictures that simply co-opt the imagery of classical Indian art. Such paintings—of assorted goddesses and Hindu symbols like the “bindu”—are both tired and tiresome. They leave the impression that Jumabhoy and Tan wish to “Indianize” the Progressives, both politically and formally. The result is that the artists’ distinct visions are lost in the fog of an imagined nationalism.

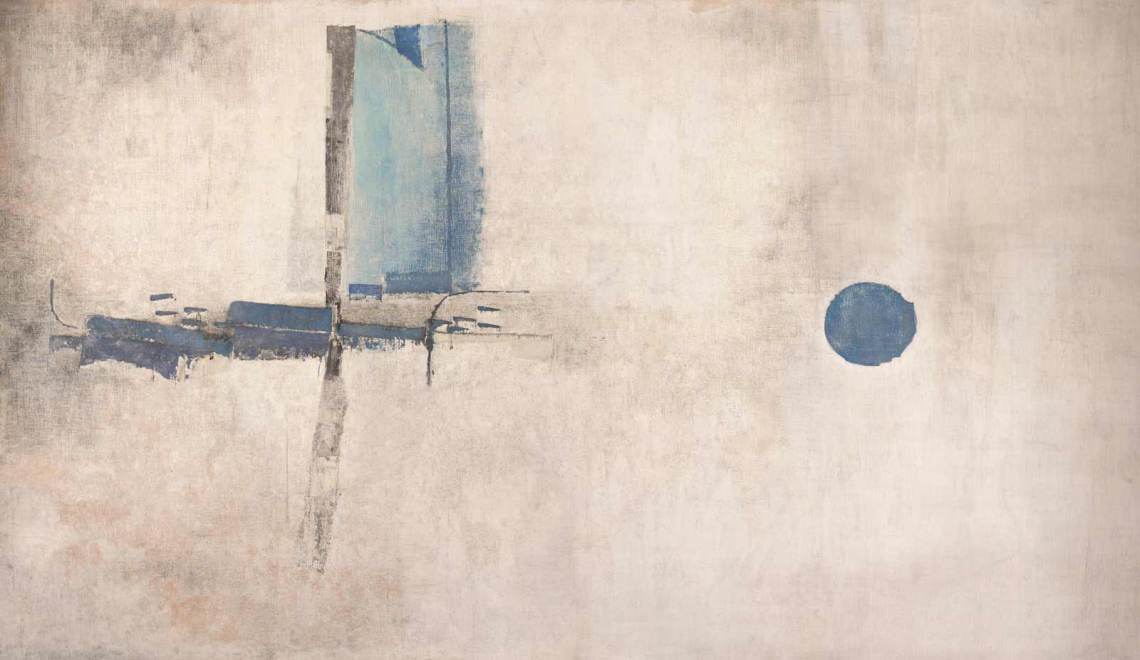

The show’s two standout artists are featured in the final section; tellingly, neither quite fits in the curators’ nationalist schema. V.S. Gaitonde, who had a retrospective at the Guggenheim in New York in 2015, makes abstract paintings that have a magnetic quality, evoking both the transcendental and the tactile; one senses the artist’s touch—he worked with brushes, but also with palate knives and rollers—yet it expresses something more perfectly aleatory and less ruffled than a mere ego. Untitled (1962) is a beautiful, murkily lit painting—like water seen under a pond’s surface—that shows a chalky expanse with passages of tonal drama that suggest the easy movement of clouds. By contrast, Mohan Samant is a deliberately, even violently, physical artist. His madcap, self-hating erotic drawings—human phalluses, obsessive textures—seem to amount to a one-person exercise in BDSM, while Midnight Fishing Party (1974), a delectable mixed-media collage, opens out to the world, combining pink flesh tones with the colors of earth and vegetation.

There’s nothing obviously “Indian” about either of these painters. Gaitonde sits as easily with Joel Shapiro and Mark Rothko as he does with an Indian artist like Nasreen Mohamedi. As for Samant, it’s hard to tell what he was looking at: Japanese prints? Brazilian concrete art? The sculptures at Khajuraho? What is certain is that they both stood at an angle—or, perhaps, at a distance—from the mainstream nationalist narratives of their era, charting a personal path as others rushed down the avenue of received ideas. Their achievement in turn reminds us that all true art, national or otherwise, is born in the fields of contemplation and desire.

“The Progressive Revolution: Modern Art for a New India” is at the Asia Society, New York, through January 20.