Dick Cheney grew up in Nebraska and Wyoming, attended Yale for two years, flunked out and went to work as a lineman. After a bad spell—a pair of DWI arrests and a resolution to change his life—he married his high-school sweetheart, Lynne Vincent, and enrolled in the University of Wyoming, where he took a bachelor’s degree and a master’s (with the help of five draft deferments). In 1969, in his late twenties, Cheney became an assistant to Donald Rumsfeld at the Office of Economic Opportunity and followed him to the Ford White House as deputy chief of staff. He was the presidential campaign manager for Gerald Ford in 1976; from there, it was a short step to a successful run as Wyoming’s sole representative in Congress.

In those early years, it may have seemed that Cheney’s true passion was electoral politics; but his six terms in Congress (1978–1989) mark the only period of his life when he was politically accountable. Adam McKay’s Vice, a mock-biopic with some interludes of drama, suggests that Cheney’s distrust of democratic exposure was an ineradicable trait. It showed already in the congressional minority report he wrote in 1987 to defend President Reagan’s extralegal actions in the Iran–Contra deal: Cheney looked on the covert channeling of money as a legitimate exercise of prerogative by the executive branch.

Appointed secretary of defense by President George H.W. Bush, Cheney planned the first Gulf War in 1990, was admired for his prudent conduct during his tenure at the Pentagon, and in 1993 retired from government to join the American Enterprise Institute, and then became chairman and chief executive officer of Halliburton in 1995. His public life seemed to have found its natural termination; Vice turns it into a joke by starting to unroll the final credits at this point.

Then something odd happened. In 2000, after a heavily publicized search for the most qualified running mate, George W. Bush picked Cheney himself (who had supervised the search) to share the ticket. In the late 1990s, Cheney had been active in neoconservative organizations like the AEI; he had met the younger Bush and helped “tutor” him in the opportunities for an aggressive foreign policy; but Halliburton was his only day-job until November 2000. “Dick Cheney I don’t know any more,” the elder Bush’s former national security adviser Brent Scowcroft would say in the mid-2000s; and it was a judgment many of his old associates echoed. The recessive and colorless functionary, the modest enforcer of other people’s orders, became an authority without a superior in the new administration. His power far exceeded the usual description of a vice president. He delivered conclusive advice to Bush with no one else in the room. His grasp was equal to his reach and—issuing orders transmitted by his two lawyer-deputies, David Addingon and I. Lewis Libby—he crushed his opponents with silent efficiency.

It is no exaggeration to say that in the years 2001–2006, Cheney enjoyed complete ascendancy over the mind of President George W. Bush and an overwhelming influence on US foreign policy, energy policy, military spending and deployments, and the determination of budget priorities by the Republican Party in Congress. The effects of this unprecedented amassing of power are well known: the shutdown of any government response to global warming; the promulgation of a Global War on Terror intended to last for generations; the bombing, invasion, and occupation of Iraq on the pretext of removing “weapons of mass destruction”; the creation of an offshore prison at Guantánamo to conceal the practice of torture and house permanent detainees in the War on Terror; the anti-constitutional innovation of the Patriot Act—a document sprung on Congress in October 2001, as if ready-made, granting new powers and secret authorities to the government under cover of necessity in the War on Terror.

One thing about Cheney seems clear on the face of his actions. Love of power had been a master clue to his character all along; and power, as he saw it, should be placed in the hands of a Republican president and used for US force projection throughout the world. How did he get his hands on the levers? “When a monotone bureaucratic vice president came to power,” says the narrator of Vice, “we hardly noticed.” The narrator adds: “He did it like a ghost.” Cheney always worked behind the scenes. He knew which hallways branched off to which offices. He also knew how the blueprints had been altered in the past and could be again in the future. When, in November 2000, the younger Bush put him in charge of the presidential transition, Cheney, armed with a cell phone, was able to appoint the cabinet and pack the agencies and departments with subalterns of proven loyalty.

Advertisement

He made the Office of the Vice President a separate entity and not an annex of the Oval Office. He received the highly classified President’s Daily Brief before the president. He kept offices in both the House and Senate office buildings; he had a conference room reserved for his frequent visits to the CIA headquarters in Langley; and at times, he worked, ate, and slept in a bunker beneath the Naval Observatory—ostensibly to secure the “continuity in government” in case of another attack on the pattern of September 11. These various burrows, and his travels between them, made him a force distinct from any other in Washington. Only with the jolt of the 2006 midterm defeat did the younger Bush begin to recognize the extent of his error in ceding so much power to one man.

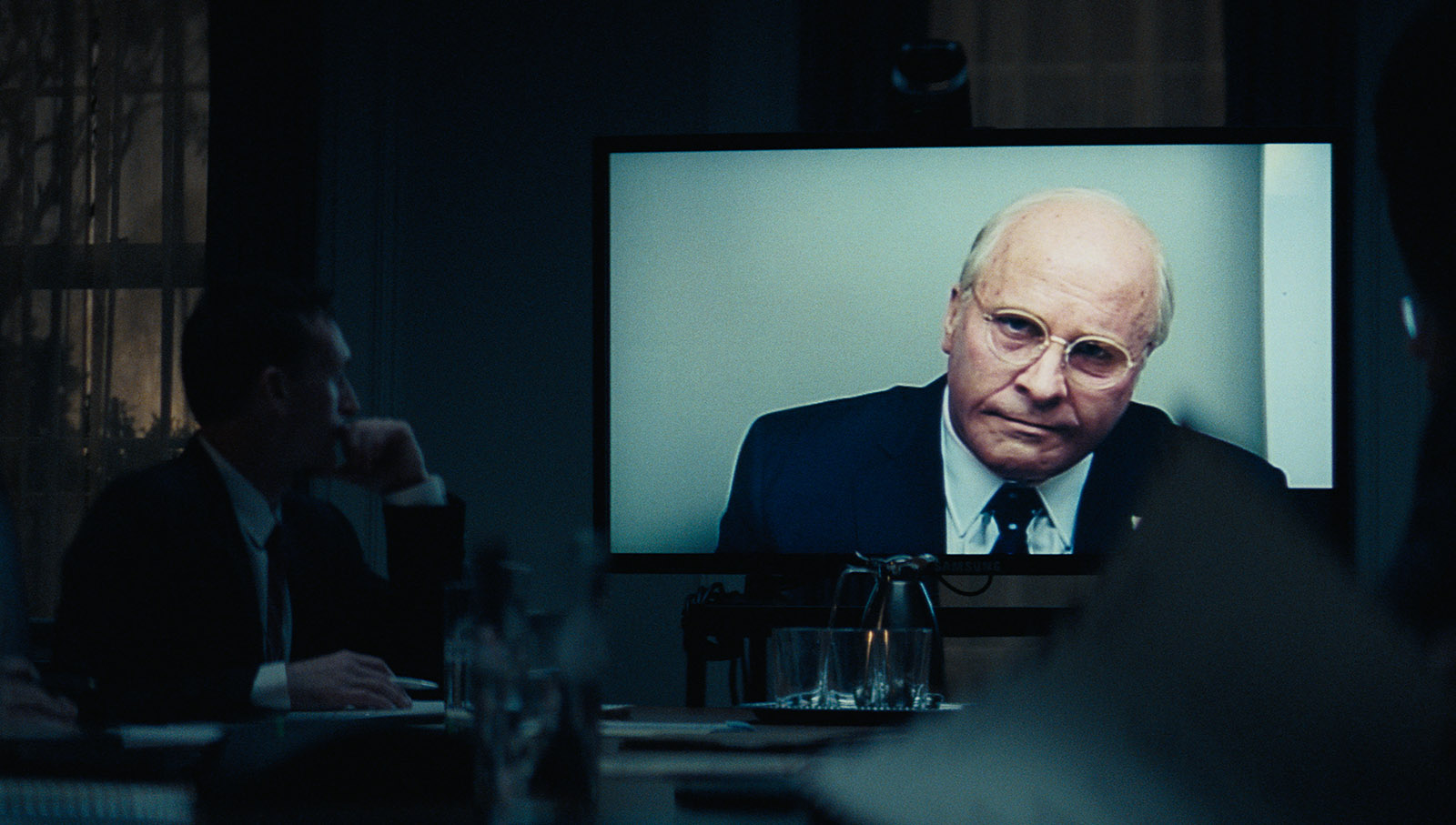

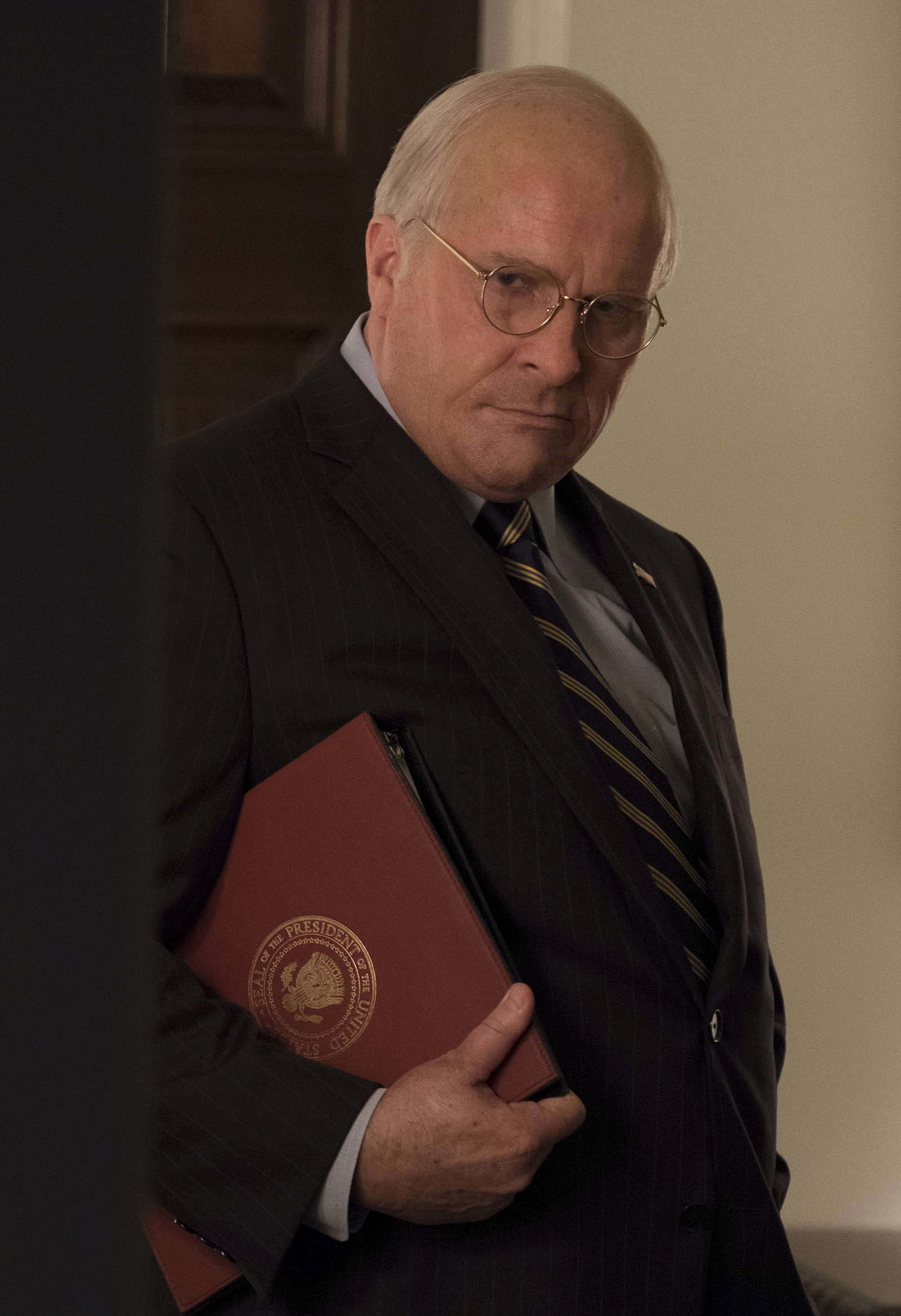

The impersonations in Vice are often inspired, and they could have supported major performances if the script had included dialogue of any substance. The physiognomy and gestural accuracy of Christian Bale in the leading role is a study in itself: he catches the downward crook of the lip, the wised-up half-smile, the flicker of contempt that was also a grimace. Cheney knew better, deeper, more, his look seemed to say; and whatever you were saying, the talk was hardly worth his while—that unspoken message intimidated many and put off the rest. The set of the jaw was the natural counterpart of the heavy gait; someone so sure of control had no need to be seen at the front of the pack. Ambition is the heart of this puzzle, and Bale makes the motive as opaque as ambition always is.

Sam Rockwell plays George W. Bush, and though the part is small—too small for the facts—he gives the film its most exhilarating moments. Rockwell has caught the smart-aleck rascality of the younger Bush that made him easy to like until he turned serious, and he, too, has mastered the distinctive expressions and gestures–the inquisitive furrowed brow, the twisted grin, the palm slapped on the table: “Hot damn!” There was real uncertainty under the boy-boy swagger, and it found a comforting presence in the elder who was not his father. Cheney’s seduction of the young president required one thing above all: a patience with process that would never compete with Bush’s love of visibility.

Steve Carell as Rumsfeld and Amy Adams as Lynne Cheney are effective in their secondary roles, the first a caricature and the second a conventional portrait drawn largely from Fifties movies. Rumsfeld was the up-front, arrogant overlord that Cheney was not—abrasive, high-handed, and bristling with self-conceit. Lynne Cheney, as the plot of Vice has it, was the woman behind the man, coaching, encouraging, rebuking on occasion, a sharer in her husband’s ascent in order to appease ambitions of her own. Nothing in the history supports this cliché. And there is more family hokum: the idea, for example, that Cheney aborted a plan to run for president because he wanted to protect his gay daughter Mary from ugly publicity. The truth is much duller. Cheney looked at polls taken in the 1990s of high-profile Republicans, saw his numbers were low, and realized that he was not meant for popular politics.

The screenplay has a few nice touches—enough to make one regret that more effort was not expended there and less on the flash of docudrama that never settles into a coherent mood. “You’re a kinetic leader,” Cheney says to Bush, choosing the fancy word for the low-key flattery, “very different from your father in that regard.” Fifty more lines like that and the film would have had the spine of a genuine story. But while it promises a sober treatment of the national disaster associated with Cheney, Vice keeps jumping nervously from the solemn to the jocose and back. It wants to be a slashing exposé and it wants to be a spoof, a stunt, a pinwheel of visual and editorial gags, in the satisfied manner of Comedy Central. You never know when the next flare will go up. “It’s a tragedy,” the filmmakers seem to say, “but hey, it’s entertainment—this is madcap stuff!”

Scandalous facts recounted in Vice (the 22 million emails missing from the Bush–Cheney White House) are unhappily mixed with non-facts (Cheney giving his other daughter, Liz, permission to come out against gay marriage). The worst of the trouble starts with the trashy-jazzy music that cues the rising fortunes of Rumsfeld and Cheney in the late 1970s and 1980s; in case we miss the mock vulgarity that covers the real vulgarity, the narrator pitches in: “It was the fucking 1980s and it was a hell of a time to be Dick Cheney.” Another non-fact: Rumsfeld advises Cheney that “any Republican not touched by Watergate is golden”—clever, maybe, but not true. Moderate Republicans like Mark Hatfield, Lowell Weicker, and Charles Percy, none of them touched by Watergate, were squeezed out of politics or defected from the party when they could not warm to the Reagan consensus on the dismantling of the welfare state and an expansionist foreign policy. Cheney’s career advanced in accord with the new mood. He would sign the Reaganite founding statement of the Project for the New American Century, an organization from whose ranks he eventually recruited the architects of the Iraq War.

Advertisement

The film goes off the rails half-a-dozen times: the scene where Cheney tells a penis joke to the murmured approval of Kissinger and Ford; the scene where the Cheneys recite a soliloquy-duet to explain their hopes and fears in pseudo-Shakespearean gobbledygook; the scene where a waiter offers Cheney the latest dishes: Enemy Combatant, Extraordinary Rendition, and Guantánamo, and Cheney says, “I’ll take them all”; the scene where the narrator gets hit by a car and he turns out to be the donor for Cheney’s heart transplant; the gruesome and pointless detail with which the surgery is enacted; and the final punt of the gag-a-thon, a focus group over the closing credits that ends with traded insults and a fistfight. By contrast, the handling of Cheney in Oliver Stone’s W. (2008) was straightforward and free of meretricious gimmicks.

Vice knows enough to have taught a solid lesson—after all, nobody under twenty-five has a vivid memory of any of this—and major talents were lined up to collaborate. But the result is a shambles. Like the genre of vaguely left-wing comedy news that took off and prospered in the Bush–Cheney years, Vice substitutes a hilarious knowingness for analysis. The narrative is so splayed and jumbled it can teach nothing to people not already in the know; even for the sophisticated, it is a hodgepodge, a half-hearted reminder. The gravity of the moral indictment is fatally undercut by the dispensable bright ideas that were not dispensed with, and creeping around the edges is the lazy conceit that we are a nation of morons anyway. More disheartening than all that is promised and not performed is the space on the shelf that Vice will now occupy. It takes the oxygen out of the subject and, for a few years to come, will discourage anyone from making the truer and more somber film the history deserves.

Adam McKay’s Vice is now in theaters.