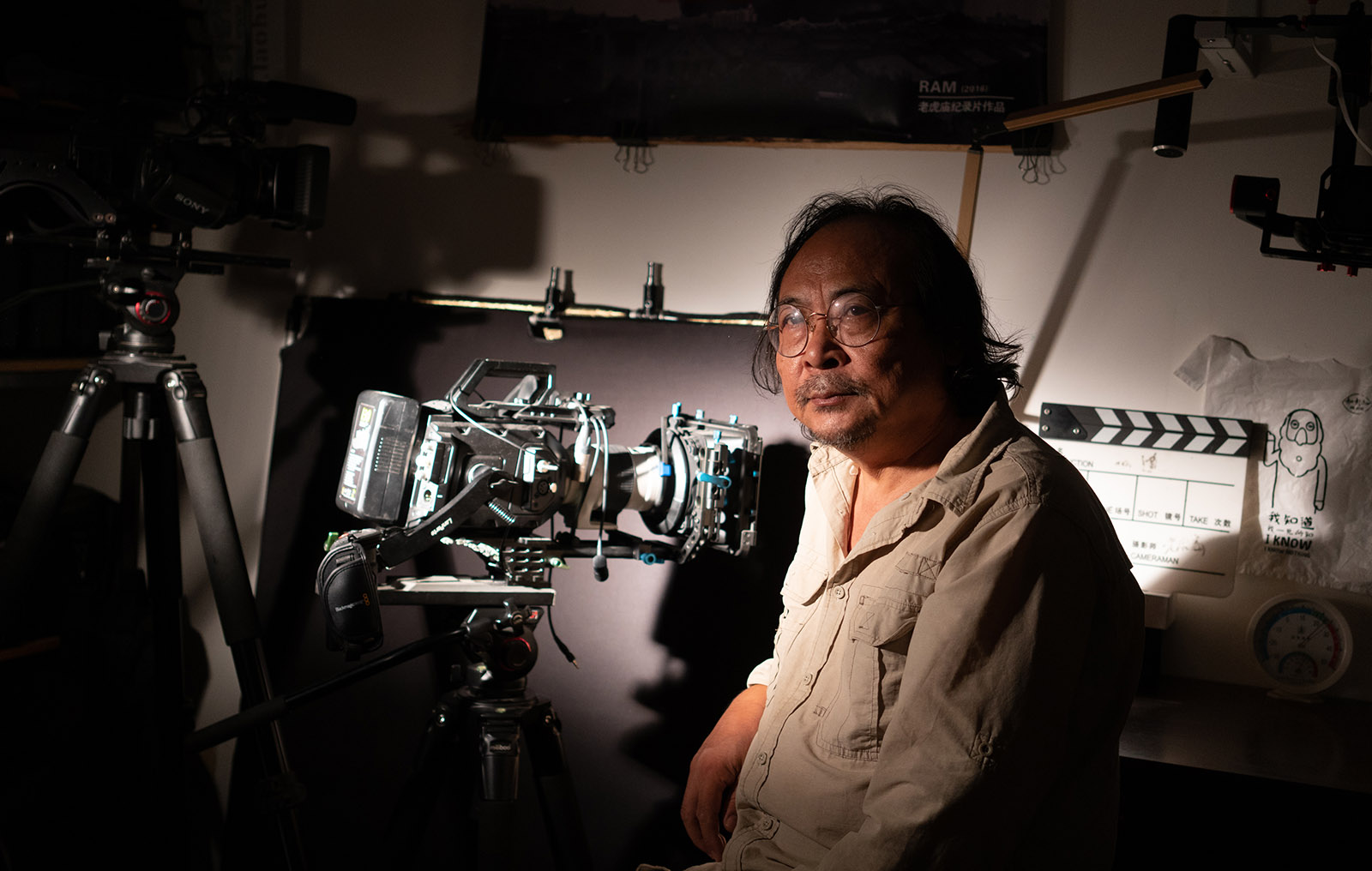

“Tiger Temple” (Laohu Miao) is the nom de guerre of Zhang Shihe, one of China’s best-known citizen journalists and makers of short video documentaries, many of them profiling ordinary people he met during extraordinarily long bike rides through China, or human rights activists who have been silenced but whose ideas on freedom and open society he has recorded for future generations.

Now sixty-five years old, Zhang belongs to a generation of people like leader Xi Jinping who came of age during the Cultural Revolution. Also like Xi, Zhang was a child of the country’s Communist elite. His father had been a Public Security Bureau official in China’s Northwest, which was also the base of Xi’s father, Xi Zhongxun. Zhang’s father was a rung lower on the ladder, but still ended his career with the rank of vice-minister.

And like the Xi family, the Zhangs suffered during the Cultural Revolution. Xi was sent off to a remote village to labor, while Zhang Shihe was a child laborer who helped build a treacherous mountain railway line. But the two reacted differently to their fates. When the turmoil ended in the late 1970s, Xi grasped every opportunity to make up for lost time and launch his political career. Zhang, however, used the freedoms of the new era to explore how China had gone off the rails.

He did this by interviewing China’s downtrodden, becoming a pioneering “citizen journalist,” a breed of self-taught activists who used the newly emerging digital technologies to record interviews and post them online, thus bypassing—for about a decade starting in the early 2000s—traditional forms of censorship.

After nearly twenty years in Beijing, Zhang was caught up in the hardening political climate and, in 2011, sent him back to his hometown of Xi’an. This is the most important metropolis in western China and also one of the country’s most famous ancient cities. I went there with the help of a Pulitzer Center travel grant late last year to find out how civil society was faring outside of the narrow confines of Beijing.

The interview below is part of a bigger project I’ve been pursuing to look at how writers, thinkers, and artists are dealing with the new, more repressive policies in China. As I’ll explore in subsequent posts and an essay in the Review, I found in Xi’an a surprisingly thriving, if small, ecosystem of critical journalists and thinkers.

Zhang lives in the eastern reaches of Xi’an, in a district called Ba River, which is one of the rivers that bounds the city. In ancient times, it was the place where travelers to the empire’s provinces took leave of friends, and was mentioned by so many great Chinese poets that it became synonymous with melancholy and loss.

When I visited, I found another sort of tristesse: the drab uniformity of modern Chinese cities. The Ba still flows but the area is now a series of endless housing compounds of fifteen-story buildings divided by razor wire and faceless streets. One subway line serves the area, its stations made of corrugated iron that was being hammered by rain when I arrived.

Ian Johnson: Why are you living back in Xi’an?

Zhang Shihe: It was 2011 and the Jasmine Revolution [the North African uprising, which also led to a crackdown in China]. I didn’t participate in that, but one day, the Public Security Bureau told me not to go outside. That was the day there were supposed to be Jasmine Revolution protests in Beijing. I didn’t even know about it, but they kept an eye on me.

I moved to Xianghe [a distant suburb] but they kept pushing me further and further out of Beijing. I was being followed constantly.

I thought: forget it, I’ll just leave. I went to Hebei Province to do an investigation and, a month later, was back in Beijing and they were following me again. I thought, Forget it, I’m leaving. So I rode back here.

You rode back to Xi’an?

Of course, I always ride my bike.

From Beijing to Xi’an? That’s 1,000 kilometers!

That’s exactly right: 1,000 kilometers. But I once rode the length of the Yellow River, so what’s Beijing to Xi’an? I ride slowly. About thirty or forty kilometers each day. I’m never in a rush. I like to stop and interview people and just move on slowly.

What do you like about this work?

I’m not so good on theoretical questions like that. Maybe the feeling of speed when reporting the news, even though I’m not a journalist. I always liked reporting. At one point, around 1990, I bought two motorcycles and got two young guys and told them, “Wherever anything is happening, you go there and report on it and bring it back to me.” And I’d write an article and send it to the newspapers.

Advertisement

At least, that was my goal. We did buy the motorcycles, but mainly smoked cigarettes and waited around. But I realized I liked news. There was some pleasure in it.

And you want to influence politics?

Politics? Don’t bring that up. But righteousness (zhengyi)—because I’m one of those people who gets really angry when he sees something wrong. No one cares, but I do. I have to speak up.

Where does it come from, this sense of justice?

[Laughs.] I don’t know! From heaven. It’s not genetic, that’s for sure. My older brother isn’t like me. He is happy to get along.

Maybe your experiences in the Cultural Revolution?

That was a very strange time. My parents were attacked as “cow demons” and “snake spirits” in the Cultural Revolution. You see, my father was from the founding generation of the revolution. He was from a very poor area, Xunyi County in Shaanxi. He worked in Public Security. But it was exactly these old, loyal officials who were attacked by Mao and his followers. Both my parents went to jail.

And you?

I was thirteen and I went traveling. I was too young to be a real Red Guard, but at the start of the Cultural Revolution, schools closed and train travel was made free so young people could travel China and experience the revolution.

We were all red. We were brainwashed and wanted to see Chairman Mao in Beijing. We got on a train the night before it was due to depart and we slept on the train. We thought we were going [east] to Beijing, but in the morning when it started to move, we realized it was heading west!

We went to Chengdu, which was in the middle of armed struggle [a phase of the Cultural Revolution when guns, and even gunboats, were used by different factions]. I spent eight or nine months on the road. I saw the most violent parts of the Cultural Revolution. We begged for food on the streets—we had no money.

When I was nearly fifteen, I got back home to Xi’an just by accident. The train stopped here so I got off. I didn’t have a penny.

People of your generation missed a lot of formal schooling.

When I got back to Xi’an, I went to classes to make up for lost time, but we didn’t learn much. It was really basic. We did math and Chinese. The rest of the time, we learned slogans about how we had to defeat nature, or learn from [the model commune of] Dazhai.

When I was seventeen, my education really stopped. Mao ordered young people to the countryside. I was sent to work on the Xi’an to Qinghai railway. More than 190 people died building that. We had to carry forty-pound sacks of cement on our backs. We were teenagers.

Of course, it ruined so many people’s health. Most were broken when they came home. They’d carry two sacks, one on the end of each pole, and carry it up the mountain. Professional track layers did twenty-eight meters a month. We did thirty-seven.

We were crazy in our revolutionary fervor for Mao. We even smelted metal. We had no training. We didn’t know what we were doing.

You’ve done a lot to help these workers. Many still come back to Xi’an to protest each month to demand compensation. You’ve recorded many of their stories.

Yes, all those old guys, over sixty, this is why they come: it’s not for money. They all have children and grandchildren. They don’t lack money. But 25,800 people worked on it, and 7,400 died prematurely after coming back. They don’t want that forgotten.

What happened to you when the reform era started?

I was ran one of the first independent bookstores in China. It was called Tianlai (Scorpion). It lasted from 1983 to 1990.

But after the June 4 [Tiananmen Square Massacre of 1989], all the interesting books were banned, especially the foreign ones. No one had an interest in reading since all the books were boring.

And then you turned into a citizen journalist. How did you take the name Tiger Temple?

It was 1997 or so, and everyone was getting online. Everyone was taking web names (wangming) as a way to be anonymous. There’s a place in Beijing named Tiger Temple. People worshipped there on their way to pilgrimages in the western mountains because the mountains used to have tigers. They were dangerous, and so they were worshipped as a way to get protection from this danger. I thought it would be a great name for myself online.

Advertisement

Beijing became your base for long bike rides. You spent five months riding along the Yellow River and produced more than forty videos, about thirty of which can be seen in China and the others, censored, are on your YouTube channel. You recorded stories about people’s livelihood, pollution, and corruption. What led to this work?

I can’t express myself well [in writing] so I think that recording is my best way. I don’t really do deep theoretical explorations. Think about it: I stopped school at thirteen and then had another year of education, mainly using an abacus. Then I worked as a child laborer on the railroad. So, for me, recording on a camera is great. I do it all myself: I record, cut, produce. I have more than nine hundred videos on Youku (a Chinese online video service).

Why bike rides? You once wrote that on one trip you had to change seven inner tubes, three tires, four chains, and a set of gears.

I like riding because you see more. I like to travel alone. You don’t bother others and they don’t bother you.

Where did you sleep?

Three places. One is the highway toll booths. My bike can’t go on the highway, but there are cars and people all the time so it’s safe. Or the entrance to a police station. That’s safe. My favorite is someone’s backyard. I don’t live in their homes. One reason is the hygiene, or lack of it. I ask if I can stay out back for ten or twenty yuan [two or three dollars]. People are really happy to do that. Then we eat and drink, and the stories come out. The next day, I’d go to the county seat, find an Internet bar, and send out the stuff.

What were you looking for on these trips?

Everyone wants to travel but few have the time. Everyone’s busy making money. I thought: I have time but no money—because I wasn’t working. I was over forty with no money. So I thought I’d travel poor. Just as cheaply as possible.

Then people began to write about me. I was in Yangcheng Wanbao [a influential newspaper in southern China] and other newspapers. People sent money. Then I got to Inner Mongolia one day and no one reported on me anymore. The guy repairing bikes said, “Hey, aren’t you the guy they reported on in the newspaper?” I said, “Maybe I am.” He said, “So why aren’t they reporting on you?” I said, “You’re right, I don’t know why.”

Later, a journalist told me: he said they issued an order that you can’t report on me. So that was the end of that. But what did I do wrong? A person can’t go investigate on his own at his own expense? But that was it. No one reported on me.

Now you’re doing longer-form videos, including a series of interviews with lawyers and activists who were involved in the rights-defense [weiquan] movement.

It’s called “Diligently Strive for Civil Society” and has fifty-one parts. You can see thirty-seven on Chinese social media, but the rest are banned inside China. I interviewed [the artist] Ai Weiwei, [the scholar and activist] Cui Weiping, [the legal scholar] He Weifang, [the civil rights activist] Xu Zhiyong.

Why is so much going on in Xi’an? Is it more open than Beijing?

No! It’s a stupid city. They don’t get what the [central] government is trying to do. It’s different in places like Chengdu. That’s an anti-Communist base! Their character in Sichuan is to rebel. All the people from Sichuan are like that.

But Xi’an is an imperial city. I went to Beijing and a taxi driver said, “Wow, you’re from Xi’an—that’s a real capital.” I said, “Beijing is too, right?” He said, “No, we’ve only been the capital for 500 years. You’re a real capital.”

But it’s not like that. [The writer] Jia Pingwa called it right in [his 1993 novel] Ruined City. It was once a cosmopolitan capital, but now it’s stupid and backward. If the officials here were a bit more competent, they’d be ten times more fierce.

After making those short videos, you’re now doing full-length documentary features, like the film Ram.

It makes me feel a bit more creative. I’m getting older and want to win prizes! I started this at age fifty-eight. I’m not young anymore and if my films are longer, then they’re longer.

Can these films ever be shown in China?

What we’re doing now is recording this and leaving it for the next generation. If we can leave something, then that’s good.

I’ve sent everything I’ve done abroad. There’s nothing we can show here in China, so we have to send it abroad. [The art curator and organizer of a now-banned independent film festival] Li Xianting is trying, but it’s almost impossible now. The last time [I saw him], we had to meet at the second floor of a hamburger joint and watch the film on two laptops. Li Xianting is such a great figure, but that’s what he’s reduced to: showing films on the second floor of a hamburger joint.

What’s your next project?

I’m building a website for the guys who worked on the railway. I’m collecting historical materials. I plan to put online all this oral history.

Why this project?

I was a Mao Zedong child laborer. Thousands died. It was twelve year-olds blasting tunnels with explosives. It was insane. I can’t record them all, but I’m going to just keep going. I’m trying to make a document. It’s my responsibility to history.

This interview, part of Ian Johnson’s continuing NYR Daily series “Talking About China,” was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.