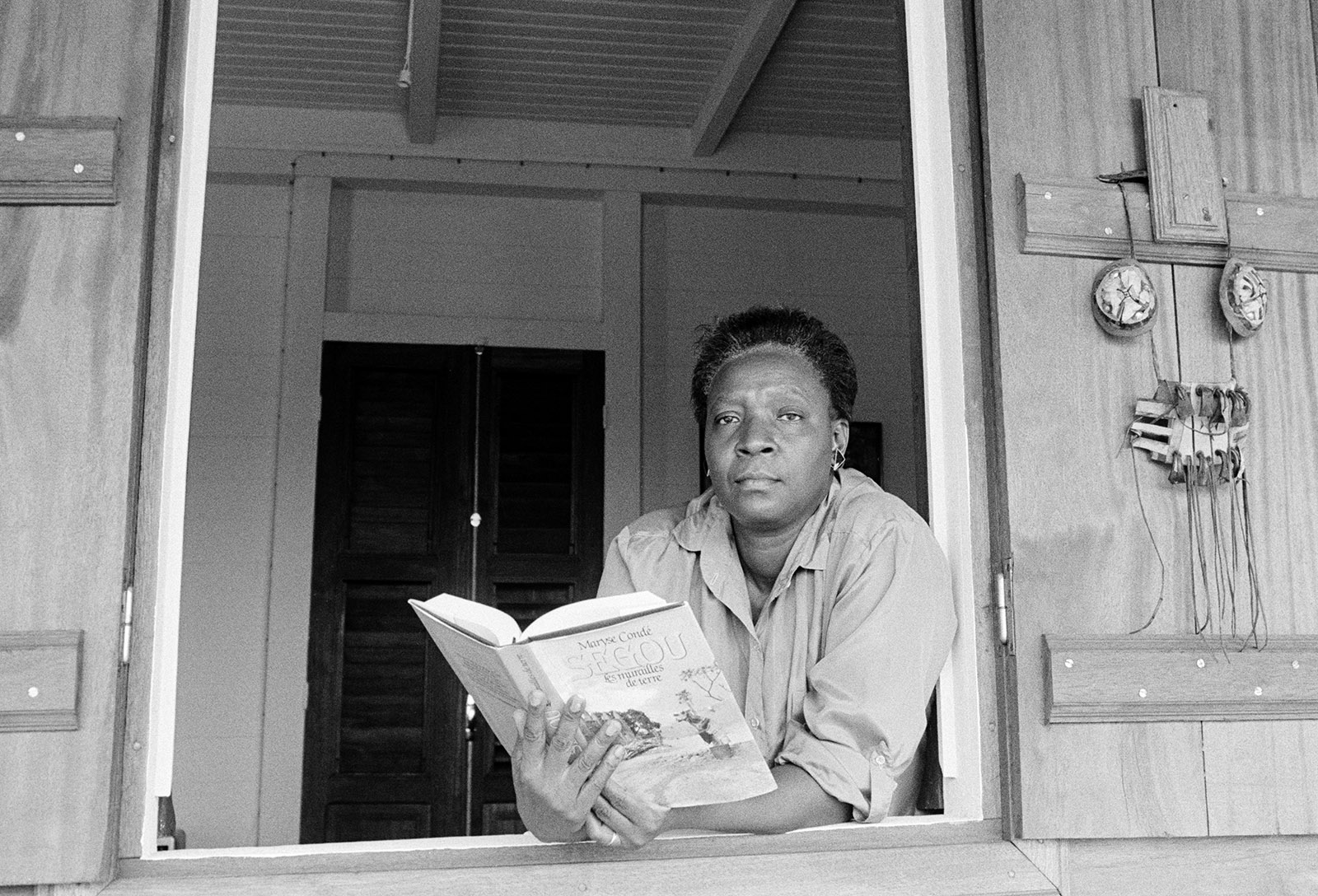

On December 9, 2018, I received the New Academy Prize for literature in Stockholm, Sweden, the award set up last year to replace the Nobel Prize, which was canceled after a scandal and dispute at the Swedish Academy. It was the second time a writer from Guadeloupe had been awarded a prize of such importance. In 1960, the poet Alexis Léger, known as Saint-John Perse, was awarded the Nobel. You could not imagine a more perfect contrast: he the descendant of the proud caste of békés, white Creoles, settled on the island since the eighteenth century; myself the descendant of African slaves who crossed the Atlantic loaded like animals in the belly of the slave ships.

The award came to me as a total surprise. Besides being proud and happy, I felt relieved. For the first time, I was at peace with myself. I had been writing for years without any special recognition. When the French gave out their famous literary prizes every fall—the Goncourt, Femina, or Renaudot—I was never nominated.

I nearly didn’t become a writer. Despite the education I received from my parents who belonged to an embryonic black bourgeoisie, I was a timid child, unsocial and vulnerable. The world around me in Guadeloupe seemed a frightening enigma. Unlike most teenagers at the time, I had no inclination to go for bicycle rides with friends to the beaches of Sainte Anne or Saint François or stroll over the Place de la Victoire, the heart of our small town, Pointe-à-Pitre. I was content only when I had my nose in a book or when narrating the most extraordinary tales to Danielle, the little Indian girl my parents had adopted. Her father, Carmélien, had died falling from a breadfruit tree, and her mother, too, died just a few months later.

I was always prepared to invent people and things. My mother, a devout Catholic, reproached me severely for making up these stories, which she called a load of lies, something I had trouble accepting. Lies? They were simply the fruit of my imagination and didn’t deserve to be called such a harsh name.

When I felt too frustrated by my mother’s scolding, I took refuge in the kitchen where our servant, Adélia, greeted me with her bad temper. She did not appreciate my culinary inventions. For her, cooking was a set of unchanging recipes that you made over and over. I, on the contrary, believed that cooking was a place for individual invention and creativity. Despite my youth, I was already preparing in my head to write an ode to my grandmother, Victoire, who was a cook to a family of white Creoles and prisoner of her illiteracy, her illegitimacy, her gender, and her station as a servant. As I set it down in the book I would eventually write, Victoire: My Mother’s Mother: “When Victoire invented seasonings or blended flavors, her personality was set free and blossomed. Cooking was her Père Labat rum, her ganja, her crack, her ecstasy. She dominated the world. For a time she became God. Like a writer.”

When I was ten, a friend of my mother’s, a primary school teacher like her but one who ordered her dresses from Paris, gave me a book for my birthday. Since she knew I had read every possible book by Flaubert, Balzac, Maupassant, Apollinaire, and Rimbaud, she wanted to give me an original present. The author’s name was Emily Brontë, a complete unknown to me—nobody at school had ever mentioned her name. The book, Les Hauts de Hurlevent, was a French translation of Wuthering Heights. From the opening pages, I was transported. I couldn’t help alternately laughing or bursting into tears. Just as Cathy exclaims, “I am Heathcliff!” so I was on the point of crying, “I am Emily Brontë!”

You might be surprised that a young girl from Guadeloupe could so identify with the daughter of an English clergyman living on the Yorkshire moors. But there is an area in Guadeloupe where the ruins of an old sugar mill and plantation house set in a desolate landscape reminded me of that setting. That’s the power and the magic of literature: it knows no borders, it is the realm of hard to reach dreams, obsessions, and desires, which unites readers through time and space.

It was the same feeling I had years later when I visited Japan. Tokyo was a city that frightened me because of its empire of neon signs giving the impression of impenetrable hieroglyphs. The Japanese are very different from me—physically, in education, cooking, and lifestyle. But all it needed was for the interpreter to begin reading the translation of one of my texts and a powerful togetherness flooded the room.

Advertisement

After this night of inspiration with Emily Brontë, I ran to thank my mother’s friend for her present and tell her the effect it had had on me. Naïvely, I added: “One day, you’ll see, I too will become a writer and my books will be as beautiful and powerful as Emily Brontë’s.” She gave me a dumbfounded and pitying look: “What are you talking about? People like us don’t write!”

What did she mean by people like us? Women? Blacks? Inhabitants of small, unimportant islands? I shall never know exactly. Yet this conversation completely shattered me. As a result, I could never begin writing a novel without thinking that I was heading for a dead end. If one of my friends, Stanislas Adotevi, hadn’t forced me to give him the manuscript I was keeping in a drawer, I don’t know whether I would have had the courage to one day look for a publisher. That was my first novel, Hérémakhonon, which means in Malinke “Waiting for Happiness.” This was an allusion to a state store of the same name in Conakry, Guinea, where I lived for three years, which constantly lacked basic necessities, empty of cooking oil, rice, sugar, and tomato sauce. Whereas, in those days, the entire world was talking of the success of African socialism, I dared to say that the newly-independent African countries were victims of dictators prepared to starve their population.

The book received bad reviews and was pulped by its publisher after six months. I immediately realized that literature is a dangerous act: never say what you believe to be the truth.

When I wrote my adaptation, my cannibalization, as I called it, of Wuthering Heights, which was called La migration des coeurs in French and Windward Heights in English, I believed I was paying homage to a writer whom I considered unique and important. For me, her book has a universal appeal. There is the love between Cathy and Heathcliff that endures beyond death; and there is Heathcliff’s desire for revenge that drastically changes his destiny and that of Cathy’s descendants. All that—the presence of the invisible among the living and the desire to avenge the harshness of life—seemed so familiar and understandable to a person from the Caribbean. Despite this conviction, after publication of the English version, I read crushing criticism from the Brontë Society, which considered my book a sacrilege.

Today, thanks to the New Academy Prize, I feel the liberation of having overcome a triple challenge: yes, women can write; yes, blacks can write; and yes, the inhabitants of a small, unimportant island, which never gets international attention, can write.

During the eighteenth century, missionaries and travelers named Guadeloupe an island paradise. Closing their eyes to the conditions of the slaves who were working in the hell of the sugar cane plantations, the colonists preferred to boast of the climate and the majestic landscapes. Even the indigenous population ended up being convinced by this counter-truth. Today, such myths cannot survive the morose atmosphere that reigns over the island.

It’s not easy to belong to this part of the world. The law of 1946, known as the law of assimilation, initiated by the poet Aimé Césaire, who was at the same time a member of the National Assembly from Martinique, transformed the island from a colony into a French Overseas Département, or “DOM.” I am not one of those who revile Aimé Césaire for his politics. He believed that Martinique and Guadeloupe were so poor that they required a political decision after World War II to acquire a status that would benefit them. I can pardon him because of the beauty of his poetry, which I discovered when I was eighteen. But let’s admit it: his politics were misguided.

The inhabitants of Guadeloupe have been deprived of their national identity and become domiens. I, too, am a domienne. They said we didn’t have a language. Creole, a language invented in the plantation system as a challenge to the white planters, was a dialect long forbidden at school; it took a group of brave intellectuals for a diploma of Creole Studies to gain recognition. They said we weren’t creative. We are either the descendants of African slaves or the descendants of indentured Indian laborers or the descendants of the French colonizers. Nobody believed that these three components could have fused to create an original culture.

Because of the colonial pact that focuses on trade based on preferences from metropolitan France, there is little work to be had in Guadeloupe. Unemployment runs high. Many of the younger population have to leave the island to make a life, mainly for France (though you can find Guadeloupeans throughout the world). Because of the desperate lack of opportunities for those left behind, some are reduced to drug-trafficking and robbery, and this violence is all you will read about Guadeloupe in the French press.

Advertisement

I belong to a political party, the Union Populaire pour la Libération de la Guadeloupe, that seeks independence. I was recently in Guadeloupe when the UPLG celebrated the fortieth anniversary of its founding. Moved by what we had learned of the horrors of slavery and ravages of colonialism from historians like Jean Suret-Canale and Jean Bruhat, we created the UPLG in the flush of our youth. We were so naïve back then that some of us believed independence was already within grasp, and that we could build overnight a socialist society in which Guadeloupeans would not need private cars but use only public transportation.

Today, the average age of the UPLG’s members is seventy. The call for independence has become the utopian demand of an older generation. The only field in which we have succeeded is the presence of Creole, which is heard on the radio, on television, and in all the media. The younger generation of Guadeloupeans no longer listens to our proposals and shows little interest in politics. A majority of the population has lost hope and motivation about the possibility of political change; they have not backed us up and I am afraid we are waging a losing battle.

Sometimes, I fear Guadeloupe has lost its voice altogether. The only time the island gets mentioned in international news is when there is a hurricane, or a transatlantic yacht race like the Route du Rhum, or when a celebrity visits, even posthumously—like the rock star Johnny Hallyday, who had arranged to be buried on the nearby island of Saint Barthélemy.

I am glad, and deeply proud, to be one Guadeloupean who has made her voice heard, thanks to the New Academy Prize. This gives me hope that Guadeloupe’s voice, despite the island’s misfortunes, remains powerful, remains magical, and still has the power to say no.

This essay is based on remarks given at the author’s acceptance of the 2018 New Academy Prize for literature.