When Victor Serge died of a heart attack in the back of a Mexico City cab on November 17, 1947, there were said to be holes in the soles of his shoes. They spoke of the poverty of his last six years in Mexico, but they also symbolized the peripatetic life of this perpetual exile.

But it is a life with lessons, for Serge and his rethinking of socialism and the left have a particular resonance today. The rise of right-wing populism, which has taken over the left’s former base, the emergence of the mixed left- and right-populism of the yellow vests in France, which rejects political parties, as well as the upsurge of a firmly democratic socialism in the US, all point to the need for the re-examination of leftist verities in which Serge engaged throughout his life, but particularly in the final years while in exile in Mexico.

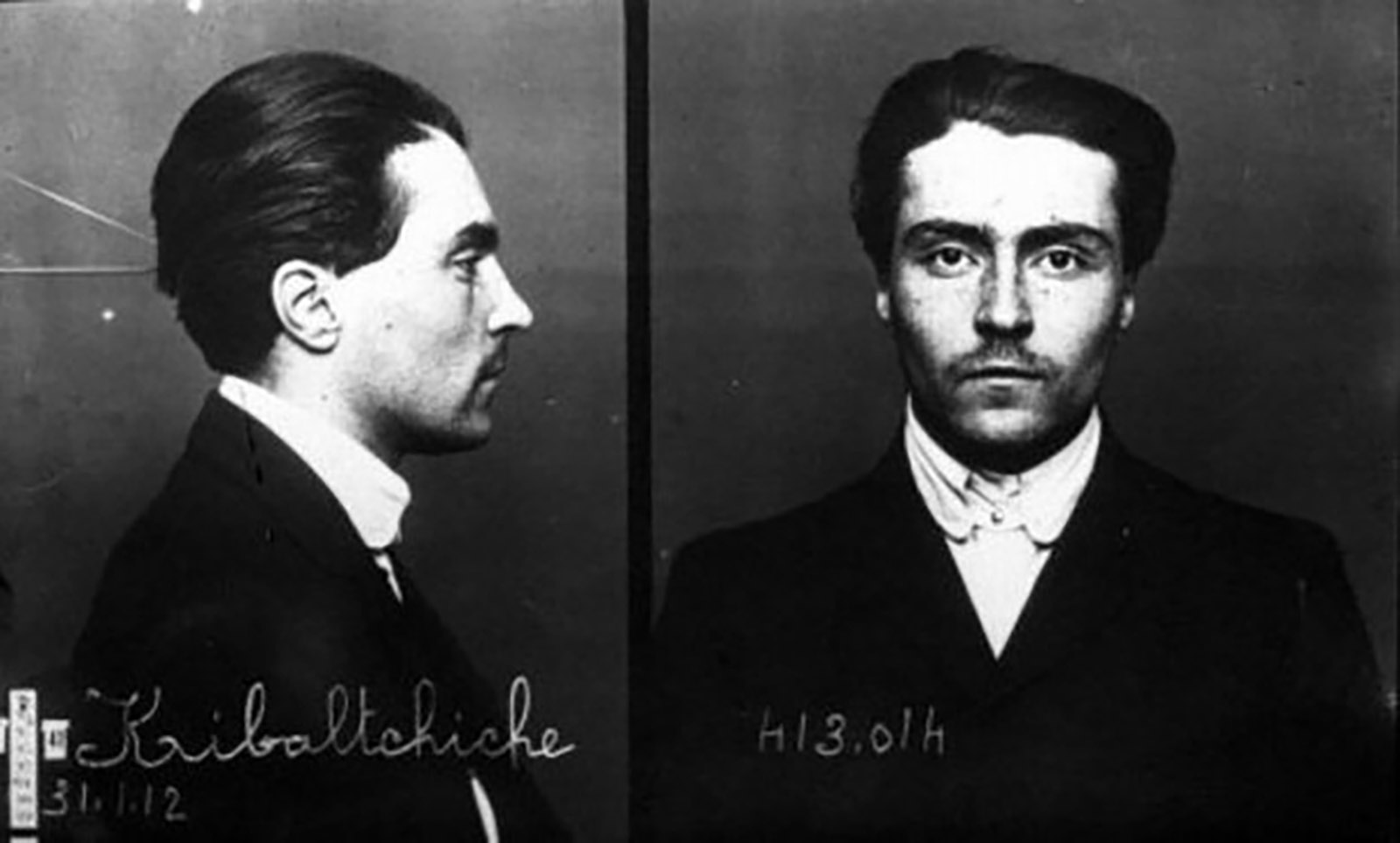

Born Victor Kibalchich in 1890 in Belgium to a family that was heir to the Russian revolutionary tradition, he belonged as an adolescent to the left wing of the youth organization of the Belgian Workers’ Party—from which he was expelled when he opposed the party’s call for the annexation of the Congo. He then took his first steps as an anarchist, and in 1909, either expelled from Belgium or leaving of his own accord (no one is certain which), he took up residence in France, where he became a central figure in the individualist anarchist movement, writing for its main journal, l’anarchie.

Arrested as an associate of the murderous anarchist Bonnot Gang, he was imprisoned from 1912 until 1917, rejecting individualism while in prison. Released, he left for Spain, where he was active in revolutionary syndicalist circles. In 1917, after some initial hesitation, he supported the Russian Revolution and returned to France illegally in an effort to find his way to Russia and participate in the young revolution. Instead, he was arrested for violating his banishment order, and was deported to Soviet Russia in 1919, where he became an apparatchik of the Communist International.

Serge sided with Trotsky against Stalin after Lenin’s death, which resulted in his internment in a camp in the Urals and his expulsion to the West in 1936, thanks to a protest campaign of intellectual and political activists. He then abandoned Trotskyism, which had by then hardened into a dogma, and adopted an independent revolutionary socialist line. This was exemplified by his backing in the Spanish Civil War of the anti-Stalinist POUM, the opposition Communist group George Orwell fought for.

In 1941, with the assistance of Varian Fry’s Emergency Rescue Committee, Serge left France for Mexico, which opened its doors to political exiles of his stripe. The ship he took from France included among its passengers the leading Surrealist André Breton, the German writer Anna Seghers, and the French intellectual Claude Lévi-Strauss, who in Tristes Tropiques described Serge as having the presence of “a prim and elderly spinster.”

Serge died poor and stateless, and a Spanish fellow-exile arranged for him to be buried in the French cemetery of Mexico City as a Spaniard alongside other émigrés. Seven years later, the term of his burial plot having expired, he was disinterred and reburied in a common grave.

Serge’s politics changed with every change of country, and it was in Mexico that he undertook his final political shift. The Notebooks 1936–1947 offer the clearest account of this shift and of just how radical it was; read along with his correspondence and articles of the period, they provide us with a complex picture.

In his final years, hatred of the Communists, who attacked him mercilessly and who he believed blocked publication of his novels, and who he feared wanted to assassinate him, became one of his central tenets. But Serge never wavered in his belief that socialism was necessary. Unlike many on the left, both Stalinist and anti-Stalinist, Serge insisted that the nature of socialism had to be rethought. In doing so, he found himself isolated within the world of European exiles in Mexico.

The Serge of the Notebooks saw that freedom and democracy were not mere bourgeois tricks: they were the essence of the radical project, the preconditions without which no permanent, positive change could occur. As early as October 1941, Serge was contemplating such heretical notions.

Social democracy was the bête noire of the hard left and had been since World War I, when the Second International split between a minority of socialist internationalists who opposed the “imperialist war” and a majority of social democrats who supported their respective national governments. But when Serge wrote about the Belgian social-democratic politician Émile Vandervelde, an exemplary member of the class of reformist politicians he had rebelled against since his youth, and who had been behind his expulsion from the Belgian Workers’ Party when Serge was still a teenager, he admitted that “one could sense in him an absolute fidelity to the working class and socialism.” Serge pointed out what he considered the error made by the Marxist left in accusing Vandervelde and his fellow social democrats of “treason.”

Advertisement

“Reformism,” Serge explained, “was a betrayal of the interests of socialism strictly from the perspective of the revolutionary class struggle, which could neither be the perspective of these men nor of the working class they so well represented.” Serge argued there was no point in attacking men like Vandervelde for not being what they never claimed to be, even going so far as to describe him as “noble.” What is more, instead of blaming leaders for the reformism of the masses, Serge accepted that the positions of a Vandervelde were those of the working class itself, which, no matter what the radical left that he’d spent his life with thought, was not by nature revolutionary, but reformist. Serge here removed a major brick from the revolutionary edifice.

His shift away from the stance of the revolutionary left grew sharper as World War II went on. The reality of this war, of this world, of the radical differences between 1917 and the 1940s, and Serge’s willingness to see these differences, forced Serge, unlike most of his comrades in exile, to completely revise his political vision.

Serge spoke up at a meeting of independent socialist exiles in Mexico City in December 1943, expressing opinions that he admits that he alone maintained. Against the “sclerosis of spirit in these militants,” who, he felt, would be quite happy to be part of a small party in France or Spain of 30,000 members, and who would like to reconstruct an International that would be little more than “a sect where they could feel at home to play at conferences, at the leaderism of minorities,” he proposed a socialist left that would “meet the masses as they are, masses who tomorrow will be objectively revolutionary and subjectively moderate.” He wanted an International that would unite the entire left, excluding the Communists (“the totalitarians, i.e., the assassins and the calumniators”), but one that recognized that revolution was not imminent.

The old schemas were out of date and, later that same month, Serge admitted to feeling an “astonishment tinted with discouragement” at the “linear and mechanically traditional understanding” of revolution on the part of his comrades. Classical Marxism needed revision: “The schematism of two essential classes is largely outmoded,” he believed, and if “we must expect powerful awakenings of the European masses, it must also be admitted that their deep-rooted moderation, their immediate practical sense opposed to combative ideology, and their traditional ideologies will remain important political-psychological factors.”

Serge also wrote of a harsh fact in the history of revolutionary activity that his fellow-exiles ignored: revolutionary fervor does not last. In Germany after their defeat following World War I, “the revolutionary effervescence began in 1918 and didn’t last beyond early 1919. In Russia the revolutionary explosion began in March 1917 and was extinguished by late 1918.” Even in Spain during the civil war, “the popular explosion, magnificent in July 1936, flamed desperately for the last time during the events in Barcelona in May 1937.” The failure of revolution, when it falls into the hands of bureaucrats after the people return to their daily activities, is foreordained.

In September 1944, in an entry written after another meeting of the socialist exiles, Serge unleashed his harshest critique of the old left, of its failure to take account of new realties. It all but signified his definitive break from the revolutionary illusion that had sustained him and so much of the left. For Serge’s comrades from the French and Spanish revolutionary left, the “Russian Revolution will soon be repeated in Europe.” What once was shall be again. His fellow exiles wrote that “‘The workers will occupy the factories… they’ll take power.’ Then the European revolution will form a socialist federation.”

For Serge, they lived in a dream world: “The Spaniards think they’ll be in Spain in six months,” while the French of the radical Parti socialiste ouvrier et paysan (PSOP) waved around press clippings saying that flyers were circulating that called for the formation of a Red Army in France. Wishes built on theories from the past had taken the place of reality, and Serge refused to accept these illusions.

His theses were that “this war is profoundly different from that of 1914–1918… That the economic structure of the world has changed… That the defeats of European socialism cannot be imputed solely to the failures of the leaders… but are rather explained by the decadence of the working class and of socialism as a result of modern technology.” His heresies grew more serious as he said that “socialism must renounce the ideas of dictatorship and worker hegemony and become the representative of the large numbers of people in whom a socialist-leaning consciousness is germinating, one obscure and without a doctrinal terminology.” And to crown it all, “That in the immediate coming period the essential thing would be obtaining the reestablishment of traditional democratic freedoms,” which alone can create the conditions for the rebirth of socialist and working-class movements.

Advertisement

Serge even questioned the viability of insurrection, of the traditional revolutionary action of taking to the barricades: “A popular revolution lacking aviation would inevitably be defeated.” What good would barricades be against fighter jets? “As a result of modern technology, the old insurrectionary methods lose at least three quarters of their effectiveness.”

The writer Jean Malaquais, another Mexican exile and later Norman Mailer’s mentor, reproached Serge for his failure to talk about the proletariat and the dictatorship of the proletariat. Marceau Pivert, the exiled leader of the PSOP, “rejects these views without attempting to refute them, and to speak of the weakening of the working class as a class seems to them all to be a sacrilege.” Serge’s response is the truly revolutionary one: “What can I do about it if it’s the truth?”

More damningly, he said that during the discussion, he “felt exactly as if he was in a cell of the Russian Communist Party in 1927.” His fellow leftists were “idealists hemmed in by the sclerosis of doctrines and circumstances, and dominated by their convictions and their emotional attachments. In short, by fanaticism.”

The working class was weakened and was not able to play the historical role that Marxists had assigned it. Democracy is the goal, he argued, for armed insurrection is futile. Serge, while never denying the need for radical change, asked radical questions about its feasibility. And he was not yet done.

The former Bolshevik was categorical about the enemy: “Stalinism… constitutes the worst danger, the mortal danger which we would be mad to pretend to confront on our own.” Not capitalism, not the Western democracies, Stalin and his agents were the enemy of a new Europe. Serge considered the defeat of Stalinist Communism a precondition for the formation of socialist movements, writing in December 1944:

I’m inclined to conclude that there will not be a possibility for the development of vast socialist movements in Europe and consequently for the establishment of non-totalitarian (democratic) regimes with regulated economies until the question of Stalinism is settled by its retreat or defeat, or by events that might occur in Russia itself.

In an article written in October 1946, Serge summarized his ideas. With socialism having “suffered defeat after defeat since 1920, totalitarian communism having stabilized as counter-revolution in relation to the communist movement, and, on the economic plane… the advent of an economy rigorously planned and collectivist,” he insisted that “it requires an idealistic naïveté completely lacking in scientific spirit to imagine that these facts, aggravated by the bloodletting, destruction, and privations of wartime could produce a socialist revolution.” Reconnecting with his anarchist-individualist roots, with its insistence on individual judgment and the need for education of the masses, Serge felt that the social movements to come, after the masses have gone through a long period of education, should aim for “the reconstruction of vast movements capable of becoming salutary forces… to check communist totalitarianism.”

Despite this thoroughgoing critique of left orthodoxies, in an article Serge published in an independent left magazine in France in 1946 on the nearly three decades of Soviet Russia, he asserted that “socialism, [as] movement and idea, seems to have a great future before it.” But what kind of socialism? It would be a socialism that defended democracy, “not just for the benefit of the proletariat alone, but for the benefit of all workers and even nations. In this sense, the proletarian revolution is no longer in my eyes our end. The revolution we plan to serve can only be socialist in the humanist meaning of the word, and more exactly socialist leaning, [and] carried out democratically, in a libertarian fashion.”

Serge died in Mexico a European, a believer in a united Europe, in Europe as the fount of culture. In an unpublished interview given a month before his death, he asserted that “Latin America, for as long as it has existed, has received all its spiritual nourishment from Europe.” Despite the destruction of the war years, he insisted he had “faith” in the coming “European rebirth,” one that will bring about a “society organized for and by the freedom to create.” The postwar Europe he envisioned would give the example of a “humanist society, rational in its organization, stable, and filled with the sentiment of justice.”

In his final days, Serge called for “the reduction—as a start—of national barriers,” and felt the countries of Europe had no future “except in federation and in cooperation with the United States.” He insisted that Germany had to be recognized as part of the Europe to be rebuilt, and that what was necessary was “the reconciliation of the victims.” His last words were not a call to the barricades, but a reminder that “all the peoples [of Europe] were crushed by the infernal machinery that dominated them. In order to be cured of this psychological block they must recreate a fraternal soul, having in sight a common future.”

The final dream of Victor Serge, an exile at the end from revolutionary illusion, was a democratic, socialist-leaning Europe. It was as if he realized that in the world emerging from World War II, the truly radical position, the idea worth fighting for despite it all, was that expressed in Orwell’s lapidary definition in The Road to Wigan Pier: “Socialism means justice and common decency.”

Notebooks 1936–1947, by Victor Serge, edited by Claudio Albertani and Claude Rioux, and translated from the French by Mitchell Abidor and Richard Greeman, is published by New York Review Books.

The main image heading this essay was originally captioned, per Getty Images, as dating from 1939; after Getty revised its caption to date the photograph to circa January–March 1941, the article was updated.