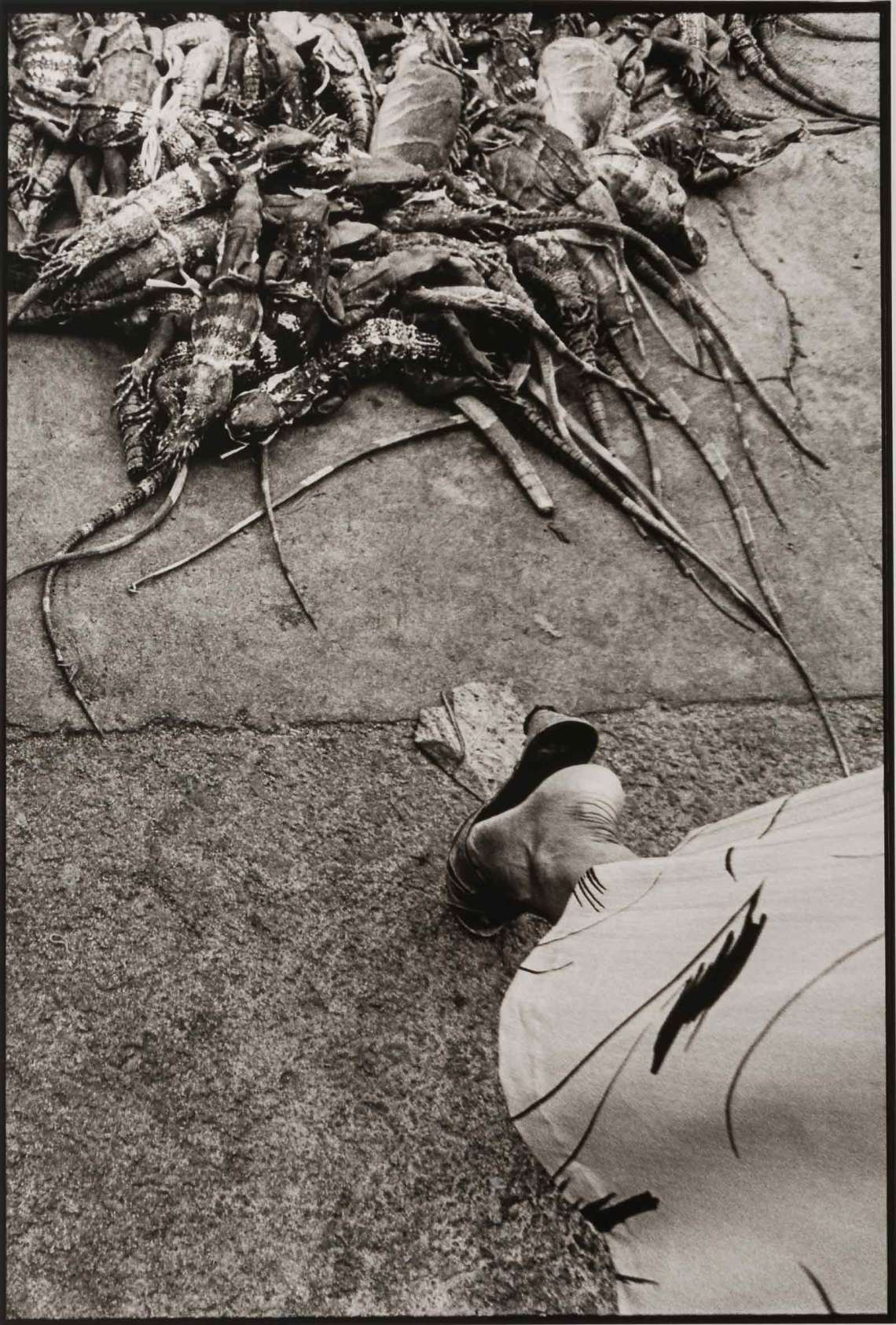

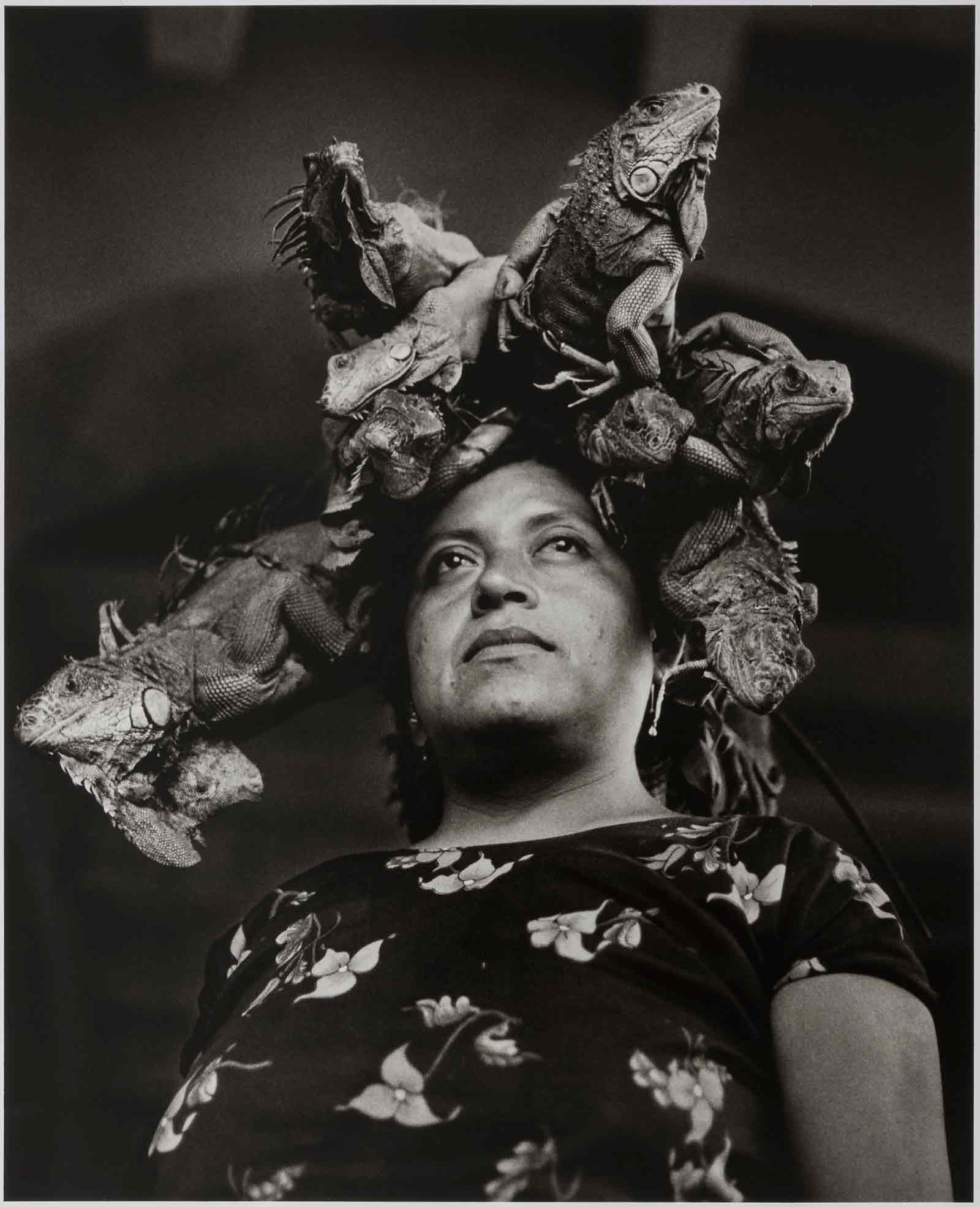

Consider the chickens, roosting at a vendor’s feet as he reads the daily news; or a semi-circle of women clutching freshly plucked carcasses—wings outspread, headless, then bundled and hung. In the photography of Graciela Iturbide, animals appear in various stages of preparation: walleyed fish dangle in pairs; severed goats’ legs herringbone across a spread of drying mats. Iguanas wreathed around a woman’s stoic face—like tentacles, or the rays of an aureole—are destined for soup. The woman in this final, famous image, Our Lady of the Iguanas (1979), is Zobeida Díaz, a vendor in the Oaxacan town of Juchitán, vaulted from the market’s everyday bustle into the realm of myth.

In “Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico”—a magnificent exhibition of approximately 125 gelatin silver prints at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—five decades of an extraordinary visual intelligence are on display. Winner of the Hasselblad Award (2008) and Cornell Capa Lifetime Achievement Award (2015), Iturbide has exhibited internationally for most of her career, but this is her first solo museum show on the East Coast since a modest traveling retrospective opened at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1998. Curated by Kristen Gresh in close collaboration with Iturbide, the show celebrates the museum’s recent acquisition of thirty-seven photographs, including two gifts from the artist. It is an overdue reintroduction to one of the world’s great photographers.

Born in 1942, the eldest of thirteen children in a prosperous Catholic family, Iturbide originally wanted to be a poet. She was already twenty-seven, a mother of three and a recent divorcée, when she enrolled at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, determined to study cinematography. But her vocation shifted again after the death of her young daughter, in 1970, when she began to obsessively photograph dead infants, or angelitos, laid out in tiny white coffins. One day, documenting a funeral, she found an adult cadaver sprawled across the cemetery path, skull and torso picked clean. “There were many birds in the sky,” she recounted. “The ones that had been pecking on the man.” It was the moment she decided to stop photographing angelitos. “I felt that Death was saying to me, ‘Enough!’”

Ever since, flocks of birds have served as a major source of inspiration—reminders of death, certainly, but also of life’s strange continuities, flesh transubstantiated into flight. Her “Birds” series is monumental: massive swarms conducted through the sky like magnetic filings, obeying an inscrutable, suprahuman logic—seemingly algorithmic, ultimately impossible to decode. The photographs hum with remembered motion, scores of stark, glyph-like wings thronged around trees, a cruciform telephone pole.

Following the death of her daughter, Iturbide worked as an assistant to her professor, the legendary modernist photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo. From 1970 to 1971, she traveled with him across Mexico, observing his process. While they did not collaborate or discuss each other’s work, he encouraged Iturbide’s interest in documenting Native Mexicans and offered advice that transformed her outlook: “Don’t rush yourself for anything,” she recalls him saying, in a captivating fifteen-minute documentary produced for the exhibition. “There’s always time.” Dedicating herself to the virtue of patience would prove invaluable in a long career marked by intimate involvement with her subjects.

The dark ballast of Iturbide’s photography is a deep knowledge of predation: how humans prey on animals; how multinational corporations subsume developing economies; how modern industry exploits a largely indigenous underclass; how artists wrangle life from their subjects in the name of creation. In one haunting early photograph, a young Cuna woman walks through an open field in Panama, Pepsi-Cola’s logo embroidered on her shirt. The pernicious creep of capitalism, yes, but also its corollary: a vivid reminder that indigenous people, often relegated to an imagined antiquity, are full participants in contemporary life.

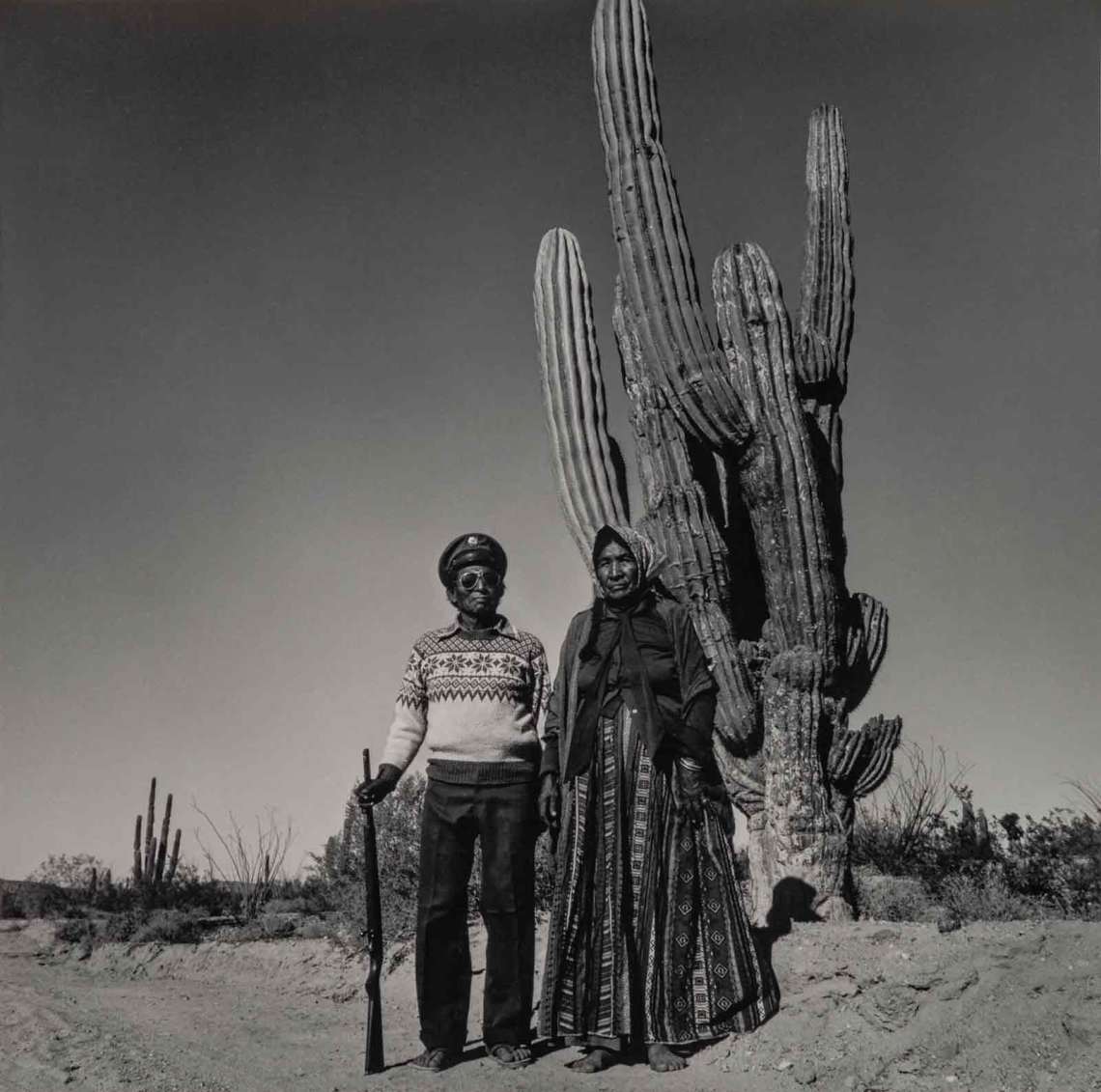

Supported by a grant from the Ethnographic Archive of the National Indigenous Institute of Mexico, Iturbide set out with the anthropologist Luis Barjau to live among the formerly nomadic Seri people of the Sonoran Desert in 1979, establishing a practice of total immersion in traditional communities that she would maintain for years. Ever wary of playing the artiste interloper, Iturbide committed herself to sensitive, and often humorous, portrayals of cultural syncretism: Manuel (1979) features a Jheri-curled Seri man clad in aviators and a frilly tuxedo shirt, drawing sartorial inspiration from the cumbia singer Rigo Tovar; Sonoran Desert (1979) depicts a couple before a towering saguaro, the man in a snowflake-patterned crew-neck sweater, the woman in traditional garb. And in the iconic Angel Woman (1979), a Seri woman scales a hillside path, boombox in tow, the desert unfolding deliriously ahead. Now one of her most famous works—it was the album cover of Rage Against the Machine’s 1997 single “Vietnow”—Iturbide has no memory of taking it. She says, “I feel that the desert gave it to me.”

Advertisement

Photographing Mexican street scenes, Paul Strand often fitted his Graflex with a decoy lens, to capture his subjects unaware. Walker Evans snapped most of his series of subway portraits from between the buttons of his topcoat. But for Iturbide, mutual understanding is fundamental. The word she uses, again and again, is “complicity”—an insistence on the affinity between artist and subject: natural lighting, no telephoto lens, full disclosure. Her sitters must comprehend her role as photographer and its implications; in turn, they are given the opportunity to refuse her camera’s eye or look back. Gresh compares Iturbide to Robert Frank and Diane Arbus, similarly omnivorous social taxonomists compelled to record “within and outside the mainstream.”

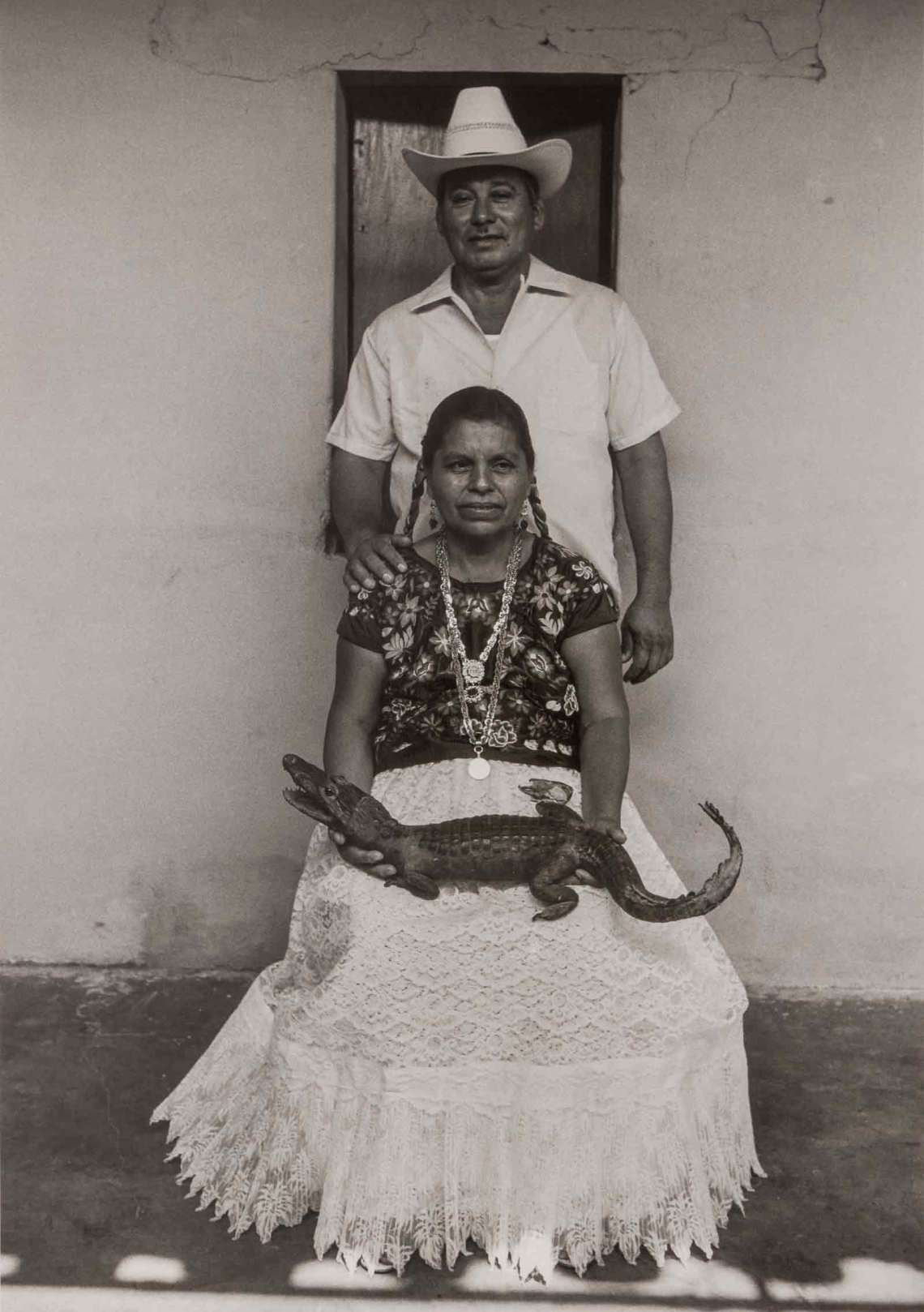

Iturbide calls her approach to photography “intuitive.” Even the posed shots, such as the winsomely deadpan The Alligator’s Godparents (1986)—staged as a family photo, babe swapped for stuffed gator—have the curious air of found art, like postcards stumbled upon at a yard sale, a mood of oddness. At the Ethnobotanical Garden in Oaxaca, she framed the region’s native flora as sculptural forms, paying particular attention to the garden’s unexpected reciprocity. Often harvested for medicinal purposes, the plants were now recipients of human care: trees pumped intravenously with pearly fluid; stands of ailing organ pipe cacti interleaved with crumpled newspapers, cradled in plank and twine.

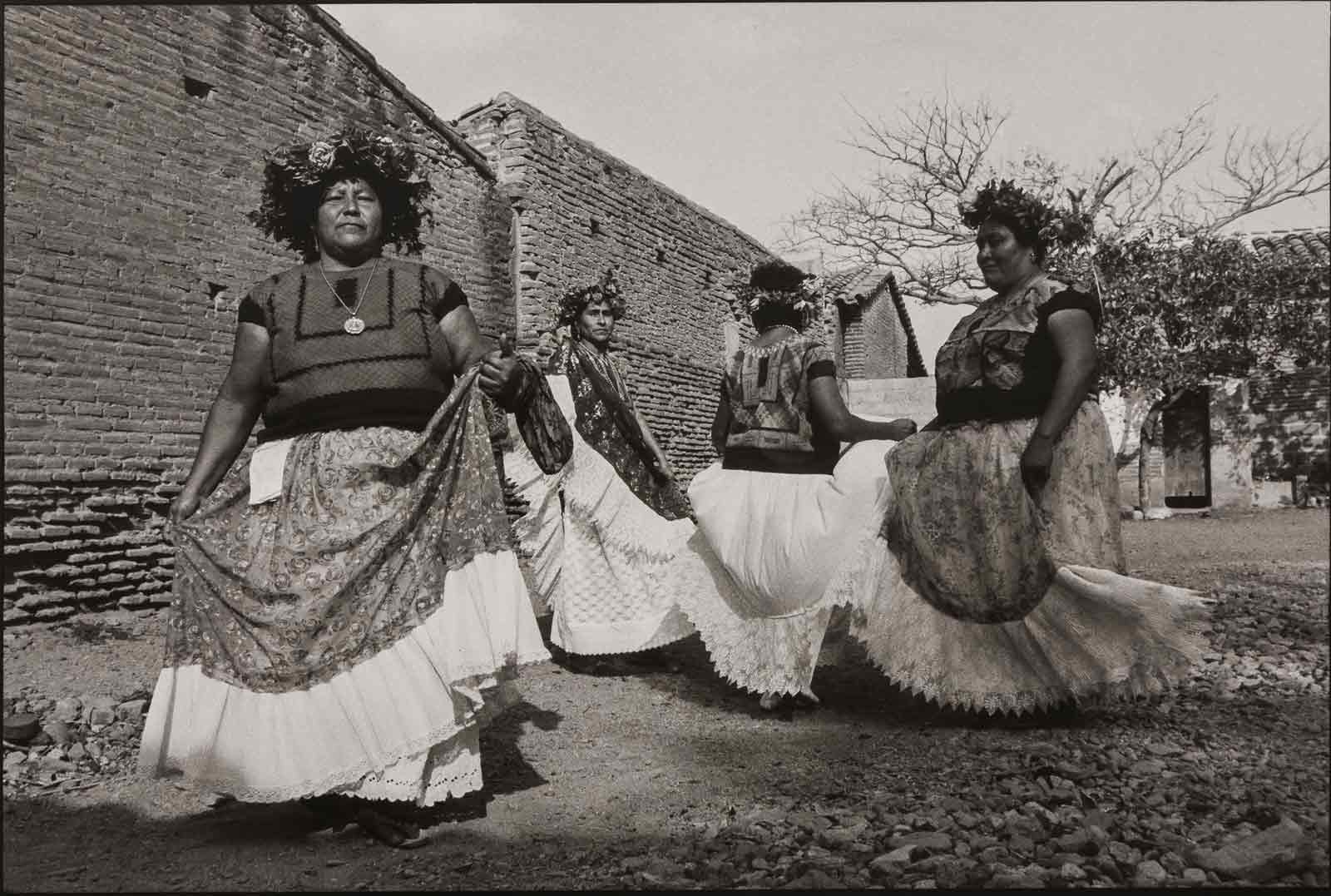

In 1979, the painter Francisco Toledo invited Iturbide to visit his native Juchitán, in southeastern Oaxaca, a town known for its fierce independence and long-standing leftist sympathies. She returned frequently over the next decade, chronicling the public and private life of its largely Zapotec population. As a perpetual guest, Iturbide became a master of the threshold, of doorways and frames, storefront windows and cemeteries, masks and carnival, of the moments preceding and following transformation.

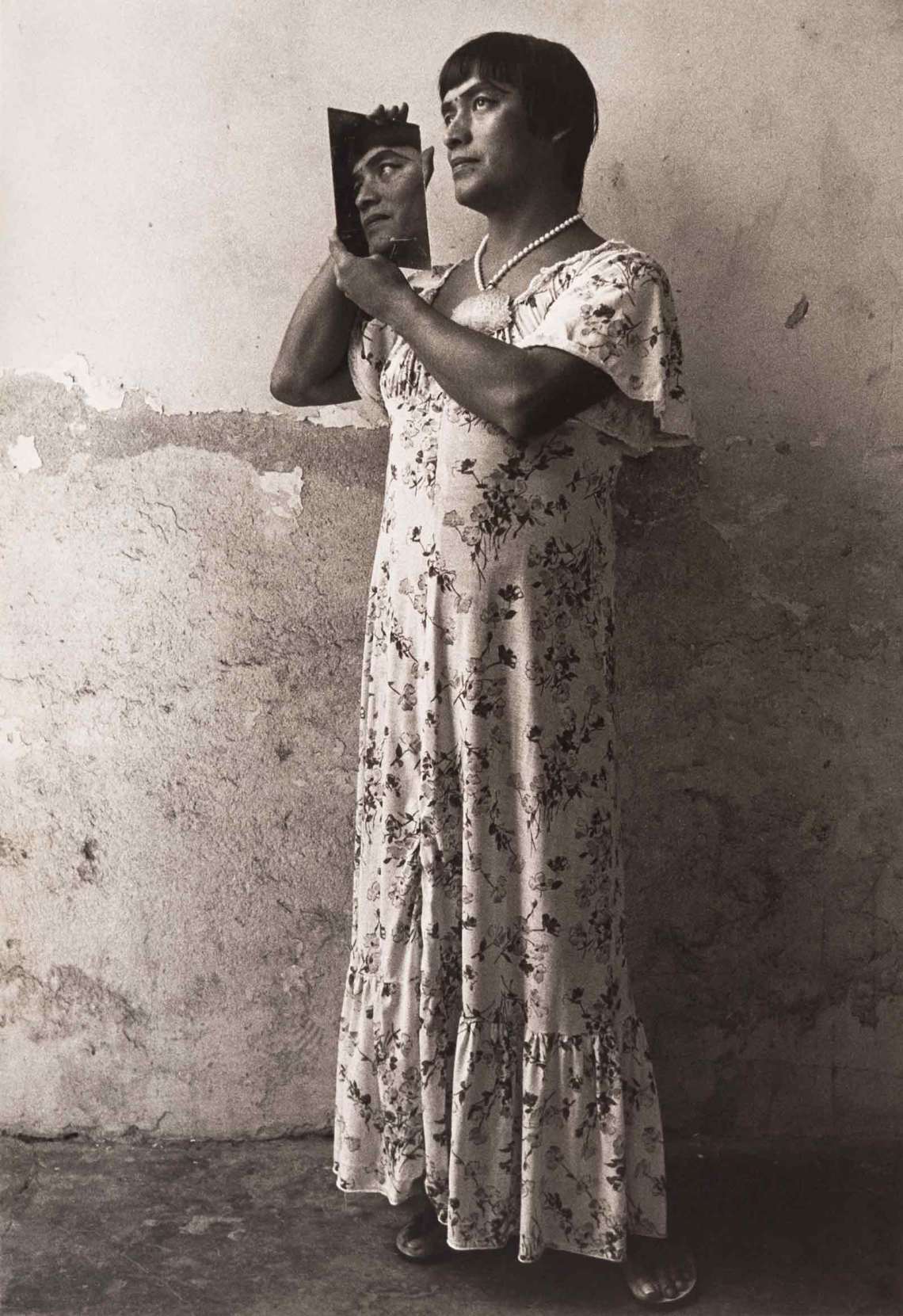

In Juchitán, the marketplace is traditionally the province of women and muxe, an identity comparable to trans and sometimes described as a Zapotec third gender. With their economic independence and social power, Juchitán’s women and muxe modeled a femininity that confounded bourgeois notions of womanhood; Iturbide called them “big, strong, politicized, emancipated, wonderful.” (Many Juchitán women have rejected the “matriarchal” label often applied to them, including by Elena Poniatowska in her essay for Iturbide’s 1989 monograph Juchitán de las Mujeres, and by a controversial 1994 Elle article that described them as “red-hot mamas.”) Some of her most affecting photographs date to this period, including Dance (1986), a beguiling scene of four women in regal dress, held in each other’s orbit, and two portraits of Magnolia, a muxe who approached Iturbide for a shoot. In one picture, her face is doubled in a handheld mirror; in another, she curtseys in a sombrero, grinning.

Contact sheets enclosed in glass vitrines accompany select images, often annotated with grease pencil. According to Iturbide, there are—pace Cartier-Bresson—two “decisive moments” in photography: “One, when you take the photo; and two, when you discover it in the contact sheet, because you often think you took one photo, and another comes out.” In the sheet for Magnolia with Mirror (1986), a livewire thread of intimacy is palpable in the sense of giddy experimentation between artist and subject. In the proofs for Our Lady of the Iguanas, Zobeida Díaz shakes the hand of a passerby, adjusts her crown of iguanas, suppresses laughter. The sheets underscore the contingency and providence of any image’s origins, how a slightly upturned lip or shifted frame catapults one into the pantheon while another slips into obscurity.

Perhaps there is a third decisive moment in Iturbide’s photography, the moment a relationship begins. When Iturbide first spotted Díaz at the Juchitán market, in her halo of iguanas, she asked to take her picture. Soon, the image became known colloquially as “The Juchitán Medusa,” and Díaz’s likeness was replicated in murals and magazines, graffiti, posters, highway signs, postcards, even in Hollywood films; as if to reverse and literalize the Medusa metaphor, a bronze statue was erected in Juchitán. Díaz died in 2004. Years later, when Iturbide learned of her unremarkable tomb, she commissioned an architect to design a new one, and Francisco Toledo to appoint it with iguanas. It will become, Iturbide expects, something of a shrine.

Advertisement

“Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico” is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through May 12, 2019.