In April 2019, Radcliffe (Ruddy) Roye traveled to Lynch, Kentucky, to photograph black miners in a town that once boasted the largest coal camp in the world. He found a community of fewer than 700 people, without industry, left behind and largely forgotten in national conversations about coal country that presume a white face. What follows are Ruddy’s images and stories from this vibrant but fading community.

—The Editors

Lynch was established in Harlan County, Kentucky, in 1917 by US Steel, which owned and ran the lives of the 10,000 residents, whom the company employed in the coal camps at the peak of Lynch’s prosperity. I say “owned and ran” because, according to the black former miners I interviewed in Lynch from April 4 through 10, 2019, they felt they had little choice in what they were ordered to do in the mines. The US’s most important energy resource at the time, the coal produced in Lynch was shipped around the country.

It was difficult, dangerous work. The mines’ shafts ran from at least twelve to eighteen miles underground. It was difficult to breathe down there, the air thick and ill-ventilated, and you were often working with water up to your waist, knowing that thousands of tons of rock and mud could collapse on you at any time. The black miners, in particular, were often responsible for doing the grunt-work of “pinning” or “roof bolting”—supporting the roof to protect against cave-ins. Though it was the highest risk job, it’s still striking that white miners trusted them with this important task, but the black miners would also be scapegoated when things went wrong.

In the early days, miners had to work sick. If a black worker called in unwell, it was likely that a doctor would be sent to the home to examine him. If the man was judged to be exaggerating, he would be told to report to the mine or, worse, fired on the spot.

For blacks, there were instances of three or more families living in one house together. Some of the miners I spoke to described men being smuggled north in the middle of the night from Alabama and other southern states. These men had to prove their worth in the mines before the company would allow them to send for their wives and families. They worked under brutish and horrible conditions knowing that any level of insubordination would lead to immediate expulsion, not only from the mine but also from the state of Kentucky.

In the Depression years, between 1931 and 1939, the Harlan County War, also known as “Bloody Harlan,” saw significant and violent battles between the miners and the United Mine Workers union on one side, and coal firms and law enforcement on the other. In the boom years that followed, just over half of the miners were black, according to Bennie Massie, who worked in the mines for decades.

The miners’ bath houses were segregated, but otherwise miners of all races worked together and depended on one another. The United Mine Workers promised better wages, benefits, and working conditions. The union established equal pay between black and white miners, and abolished payment in the form of scrips, which could only be redeemed at the US Steel-owned commissary—the notorious “company store” that turned miners into little more than indentured laborers—in favor of regular pay checks.

But the coal firms put all their resources into union busting. And by the late Nineties, the power of the union was mostly broken up, Massie said, thanks to the modernization of the mining industry, the advent of new technology, and alternative energy sources. There are still a handful of miners in the Lynch area, but according to those I spoke to, not one is black anymore.

The decline of the industry has entailed an exodus from town, with many people leaving Lynch to move north to Indianapolis, Detroit, and Cleveland for better opportunities. Today, many of Lynch’s remaining black residents are retired. The average age of the town is about sixty-five, by my estimation, and I was told that most young people leave directly after high school, either for jobs or to attend college.

The black former miners are troubled that no one knows their stories. The nation’s news media, and even the publishers of literary memoirs, feed the myth that the forgotten people of Appalachia are essentially hardscrabble white folks. This can be used as an explanation for Trump-supporting racism and destructive “white trash” stereotypes. It also erases the truth of the historical black presence in Appalachia.

“Trump was just trying to get the vote, we all know the coal industry is changing,” Massie told me. He and others are disturbed that black miners are not only erased from the region’s narrative today, but have been undervalued throughout its history.

Advertisement

“Everybody knew, growing up, that if it wasn’t for the black coal miners pinning the top and making it safe for everyone else, they would be no coal mining in Appalachia,” Massie said. “Even when they were at the mines, no one talked about the contribution of the black man as a coal miner.

“They talked about their people, but never about us, and how our services were used to build this country. We were responsible for training the young white miners who then were promoted to be managers and the bosses over us.”

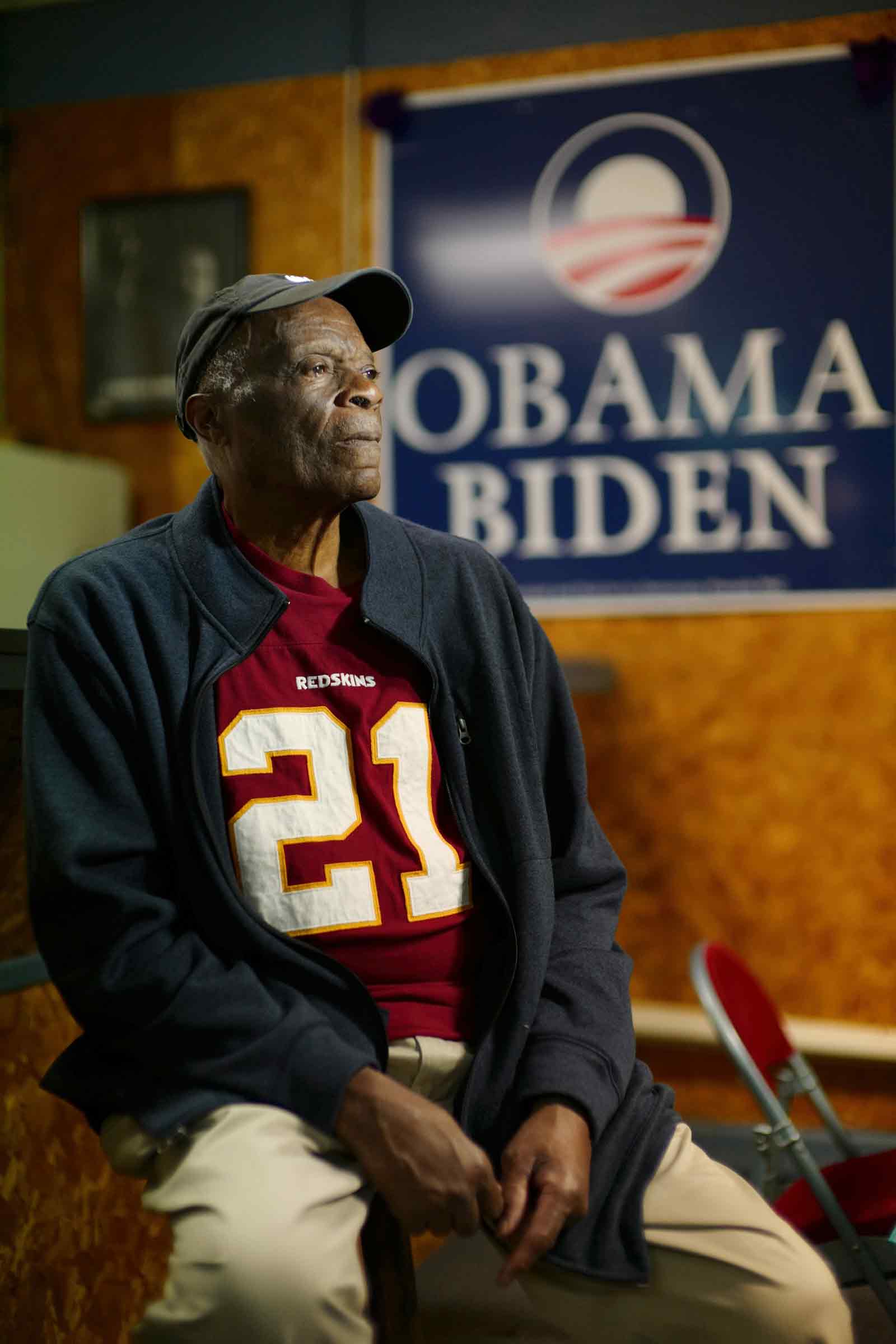

The men I spoke with believe that they are the last black former miners left in Lynch, and they’re worried that once they die, their stories will go with them. Housed in what was once a segregated black high school, the Eastern Kentucky Social Club has provided a community home for thousands of black Americans with ties to Lynch, many of whom have moved away yet still participate in annual reunions. The women at the Social Club, many of them wives of the former miners, sat separately, chatting amongst themselves. There was a sense of the priority of family, and of the importance of familial support.

With the hundredth anniversary of the Social Club approaching, the former miners are hoping to secure the funding and authority to turn the site into a protected museum and heritage site. But with few resources, they feel their hands are tied. To them, my arrival to Lynch and this interest in their stories was a “godsend.” They hoped that these images would help preserve their legacy.

Bennie Massie met me at the Hardees store in Cumberland, near Lynch. It wasn’t hard for us to find each other. I looked up from my phone to see a man of medium height, dark skin, and a burly frame who wore starched but weathered clothing. I immediately knew that it was Bennie.

I’d been put in touch with him by Robert Gipe, who produces the Higher Ground community performance series in which Bennie participates, a traveling theater troupe that visits universities and other organizations. The photographer Roger May connected me with Gipe, who hooked me up with Bennie.

Bennie grinned widely, flashing bright white teeth as he approached my car. Everything about him—his gravel baritone and smell of wood smoke—reminded me of a well-aged moonshine. The strong right hand he stretched out to greet me seemed to cast a shadow, the way the Kentucky mountains loom over the valley of Lynch.

“It ain’t big,” Bennie said of his home. “It was a coal mining town. Got my thirty years in. This town right here had everything you needed in it. It had over 10,000 people living in this Benham-Cumberland-Lynch area; 5,000 of them were miners. We were producing coal for the nation, we produced coal for both World War I and II. We were shipping coal out of here…

“It’s rough working. You are going into a whole new world, underground. I don’t advise nobody, no kids, nothing, to take that job. They are smart enough to get that coal now [by mountaintop removal mining and other industrial changes] rather than to go through what I went through. There was mud and water and crawling, it was unreal.

“How can someone work in this stuff? But then you get immune to doing that kind of work. After you be there on the job for so long you learn the job. It’s just like anything else. Once you stay there long enough it gets easier and that is what happened to me.”

Reverend Ronnie Hampton, the local pastor for the Greater Mount Sinai Baptist Church, spoke with me after his first Sunday church service. “Without industry, this town is dying slowly,” he said. Hampton was a miner, too, and when he retired he became a reverend.

“God is working it out,” he said in his sermon, recounting episodes of suicides and mass shootings across the country. “I think about our children. They have no hope. They don’t know what they future holds. They think that all they see is all there is. It is easy to get discouraged when [bad] things happen to us. When they laid off all the older men at the coal mines, I imagined all the men were asking, ‘Why is this happening to me?’

Advertisement

“But it is not the whole picture. That was just part of the picture,” he went on. “Things that happen are just one piece of the puzzle. All the parts of our lives work together to tell the whole story. We need to give our children hope so they can have the full picture.”

Rutland Melton, a deacon in the same church, said that after three years of service in the military, including a year in Vietnam, a year working for Chevrolet in New York, and four years in Columbus, Ohio, working two jobs trying to make ends meet, he got a call from his mother back in Lynch saying that US Steel was paying $50 a day in the coal mines. He returned in 1972 and worked as a miner until he retired in 1998.

“Everybody knows everybody,” Melton said. “If one person is in trouble it means that everyone is in trouble. The first day I was scared. I had never been in a mine. But once you get in there, you don’t think about being scared. You think about the dollar. It was dangerous work. The twenty-three years that I was with the mines I am not going to say I was lucky I did not get hurt, I was blessed.”

Rutland, like many former miners, is suffering from symptoms associated with black lung. He uses supplemental oxygen for episodes of shortness of breath.

George Smith, who is also suffering from black lung, had a stroke a year ago. After spending over a decade in the mines, he told me, he is proud of what he contributed to the American economy: “They will remember us because of it.”

I met eighty-eight-year-old Gene Austin, the son of a sharecropper from Chambers County, Alabama, at the Eastern Kentucky Social Club headquarters. We were at a birthday party, and some of the men’s eyes were glued to the television set watching Virginia and Auburn competing in the NCAA championship game to challenge the winner of the Texas Tech–Michigan State game. It was a rowdy group of guys, and there seemed to be a close bond between them. As indeed there was—I learned that they had all worked in the coal mines together for decades.

“The lifestyle here was so different,” Austin told me, “because to come to work in the coal mine, the union mine, it’s no race or this and that—it was just one race of people. The houses were the same, pay scale was the same, and everybody was treated the same. And we were not used to that. I was thirteen when I came here.”

“My life was hard in Alabama,” he went on. Working on the family farm, mostly surrounded by white people to whom he was forbidden to speak unless addressed first, he felt lonely. “I didn’t miss church or school, because that was a way of seeing and playing with other black children. The lifestyle in the mines was a big change from life in Alabama.”

Deon and Demarco, brothers heading to the basketball court when I stopped them on the street, had recently moved to Harlan County. They said their mother moved the family to Harlan because she couldn’t find work where they’d lived before. Deon, fifteen, said that while the move was hard on him and his twelve-year-old brother, because they had to change schools, he understood why his mother needed to move in order to find work. I didn’t find out whether or not she got the job she hoped for.

Michael Ellington, sixty-one, was born in Lynch. We sat in his house on Main Street to talk about growing up poor in a family of fourteen, wearing hand-me-down clothes, to now owning multiple properties in Lynch.

Michael took me riding in one of his all-terrain vehicles up to the top of the Appalachian mountain ridge to show me how he escapes the stress of everyday life in town. After high school, he worked in the mines for nineteen years, until he was laid off.

He has the distinction of being one of the few living black miners who worked for both a union and a non-union mining company—the latter part a history that is often met with disdain among locals. According to Michael, though, “I had no choice. I had a family to raise and I had to do what a man had to do; it was an honest job.

“In the union mines, you had a dinner break—you could go sit down and eat. In the non-union mine, you ate on the run. In the union mine, it was eight hours and then the shift was over. In the non-union, you worked until someone came to relieve you. But it was a job, I supported my family doing it.

“I worked sixteen hours a day, six days a week, and eight hours on Sundays, day in, day out. Many days, I didn’t see what a sunset was. I went in when it was dark and went home when it was dark.

“Coal mining is a rough life. I have traveled eight miles underground with only the light on top of my mining cap. I worked in water and dust. You would disappear when the dust would wash over you.

“Other than a memory plaque on the school building, there is nothing that tells the story of who worked and survived here. It is as if we never existed.”

J.D. Wilkes reached over my shoulder to beckon me toward a back wall at the Social Club plastered with photographs. He wanted to show me one particular image of his father, who stood proudly in the back of a line of baseball players. But he also wanted to show it to me as a visual archive of Lynch: each photograph on the wall had a story, he told me. Most of the people pictured have “either moved away or have moved on,” he said, but the wall of images attests to the past in the way that the surrounding coal-seamed mountains, always visible, remind its residents of what Lynch once was.

Regal in her red bathrobe, Dorothy Wilkerson, ninety-four, was born in Lynch. She is J.D. Wilkes’s mother. She gently shuffled across the verandah, her wrinkled face seeming to hold stories. With a smile, she quickly opened her hands, her fingers covered in rings, and began to tell me a story about her childhood. She wanted to tell me about growing up in Kentucky as a black child.

“My grandfather and grandmother lived in Knoxville, Tennessee,” she said. “My grandfather worked on the railroad. In the summer, he would send us passes and we would catch the train and go to Knoxville [to visit]. My great-great-grandmother was sold into slavery. The white man that bought them bought the whole family, he didn’t separate them.

“She used to tell me,” she went on, “‘Little one, I am going to make you some popcorn.’ Then she would say, ‘I am going to make you some ash corn bread.’ I didn’t know what she was talking about… But she took the poker and she shook a little of the ash on the top after she done cover the bread with a wet paper bag. She would shake it and when she turned it over it would be so pretty and brown and, oh, it tasted so good. We would always be saying, ‘Make us some corn bread!’ We would eat it on the three-hour train ride coming home.

“On the way to Knoxville, we never came off in London or Corbin, Kentucky. They didn’t allow black people there—you didn’t even get off the train. But one time, I got off the train to get a sandwich. I went in to order. [The woman working at the counter], she looked at me and asked me what I wanted. I said I would like a sandwich.

“She said, ‘We don’t serve niggers here.’ She told me to go around the back and purchase it through a hole. I said that I will never buy a sandwich through a hole. I was about twelve years old at the time.”

Terry Tinsley was born with club feet and wore braces until his senior year in high school. In its heyday, Lynch was a huge football, basketball, and baseball town. Because of his physical drawbacks, Tinsley said that he grew up mostly alone. He was never picked for any of the teams. He never had a girlfriend. He told me that he started working at the mine when he was eighteen years old.

“I went into the mine because at that time, it had job security. All the men I saw in the mine had a good life. Men like Bennie. I never knew who my father was until I was eighteen. I was poor. I was never college material.

“My grandparents raised me,” he continued. “My grandfather died right before I went into the mine and so I immediately found a job at the mines so that I could start taking care of my grandmother. My grandfather did not work long enough in the coal mines before his injury so she could qualify for a survivor’s pension.”

This project was made possible through the support of the Eyebeam Center for the Future of Journalism.