Eros lives in Brooklyn, in a two-bedroom walk-up off the Grand Street L, probably with roommates. You might have seen him dancing past midnight at Metropolitan on Lorimer Street, or walking his dog under the Manhattan Bridge. Maybe you’ve exchanged messages on Grindr; met at a friend’s birthday drinks; made eyes on the subway, in the locker room, during a poetry reading. Elusive, mysterious, overbooked, uncomfortably attractive—the type of boy in Louis Fratino’s paintings seems both ordinary and timeless, fellow subway passenger and saint, superficially of the moment but rooted, also, in a deeper, stranger classicism.

The twenty-five paintings in “Come Softly to Me”—Fratino’s first solo show at Sikkema Jenkins & Co.—range from gem-like portraits of friends and lovers to larger scenes of city life to a trio of alluring box lids, each measuring roughly 3.5 x 3.5 inches. Known primarily for his graphic but tender representations of queer intimacy, often set in the same apartment, Fratino here swaps domestic tranquility for psychogeography. Many of the featured works were made following a breakup, during a period marked by long walks around the city; they certainly embody an ambivalent relationship to this sudden windfall of hours. For all the new faces and encounters, the prevailing mood is one of charged solitude.

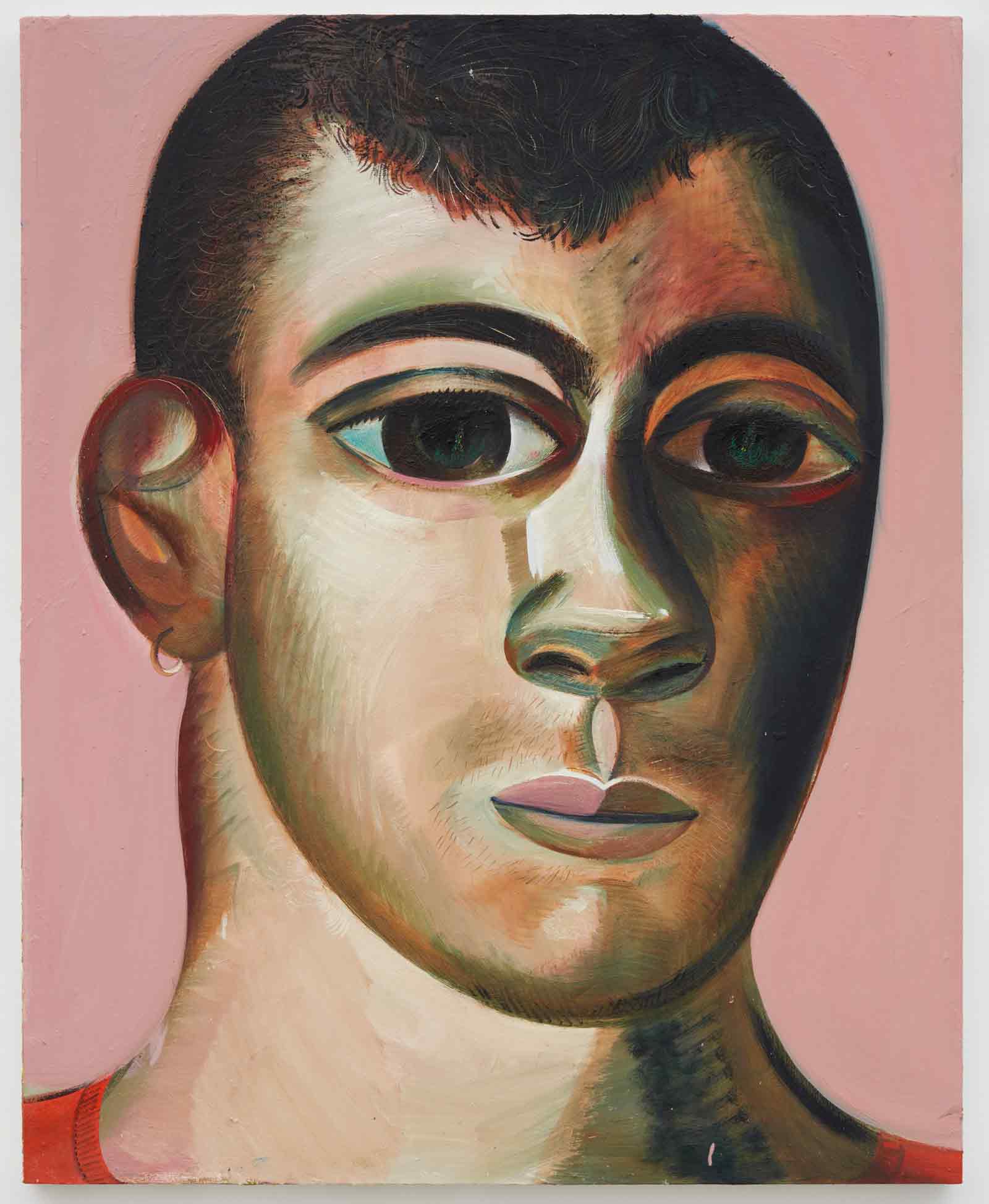

The show opens with a massive self-portrait titled Me (2019): Fratino’s face half covered by shadow, a shy smile playing across his lips, fist-sized pupils flecked with green, like solid orbs of malachite. Despite its aggressive scale, the image is gentle, even welcoming, floating on an unbroken plane of millennial pink. Beside it hangs a modest painting of the Chrysler Building, certainly the loveliest of Manhattan’s skyscrapers, its spire of stacked parabolas against a soft pastel gradient. The personal supersedes the monumental; the scales are switched, like partners in a dance. The kitchen table, the beloved, a hairy armpit: all loom larger than the Art Deco landmark.

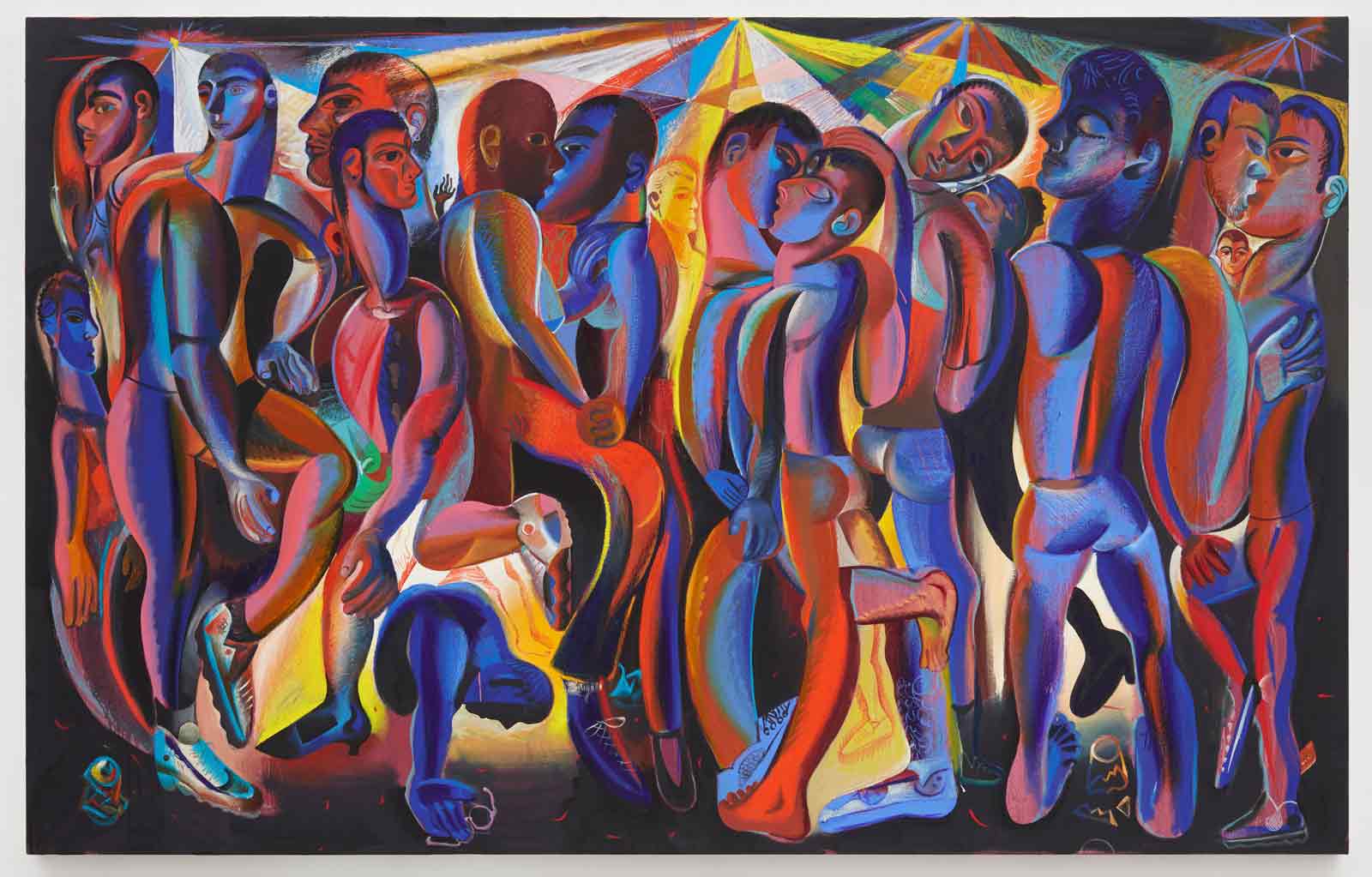

This show represents a shift for Fratino toward more expansive canvases, of individuals adrift or enclosed in wider ecosystems. Metropolitan (2019), an ambitious dance-floor tableau, recalls Nicole Eisenman’s beer gardens or a Bruegel wedding: a carnivalesque accordion of bodies, writhing and grinding under prisms of refracted light; a lusty blur of muscular, stylized forms caught in syncopated columns of red and blue and gold. A loose, screwball humor animates the scene: from between the profiles of a kissing couple, a tiny face peers out at the viewer, a thin wisp of mustache on its upper lip, sober as an Egyptian funerary portrait; elsewhere, a felled reveler crawls on the ground, groping for his glasses.

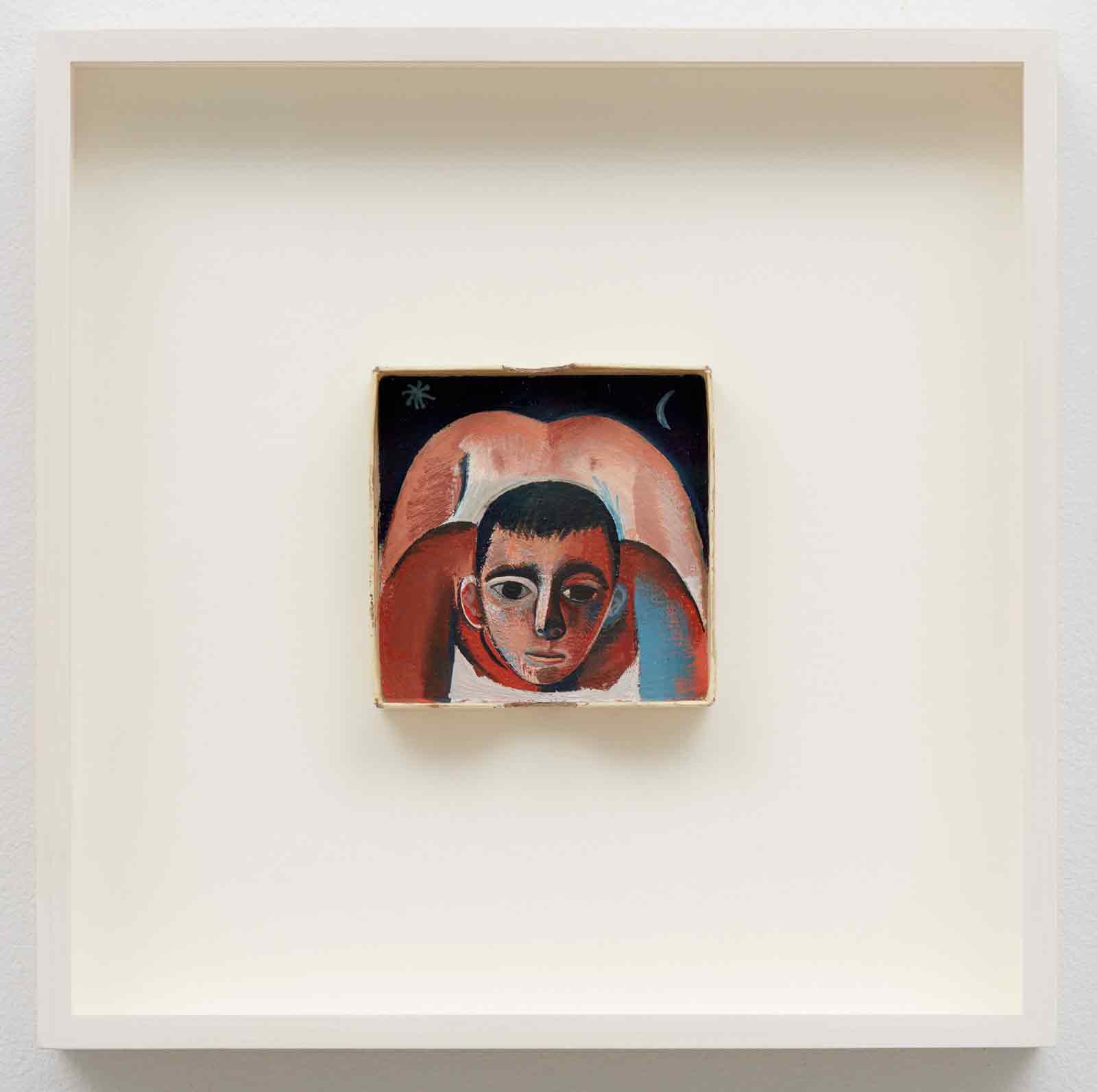

Small is still Fratino’s forte, and the miniature box lid proves a surprisingly satisfying medium. Lilliputian and fine, the most charming is Blowjob and Moon (2019), featuring an arch-backed boy bent low, moony-eyed and willing. (The lid is suggestively notched at front and rear.) Like erotic playing cards or private talismans, the works all but ask to be possessed, shared, and circulated. Sketches and studies on the artist’s Instagram reveal a prolific talent willing to experiment with form and material (plates, carpets), and a keen promoter of his peers, including the excellent Nikki Maloof. Many of these works were instrumental in establishing his reputation as one of the rising talents of his generation; many have already sold. It may be decades before they reemerge in the public eye.

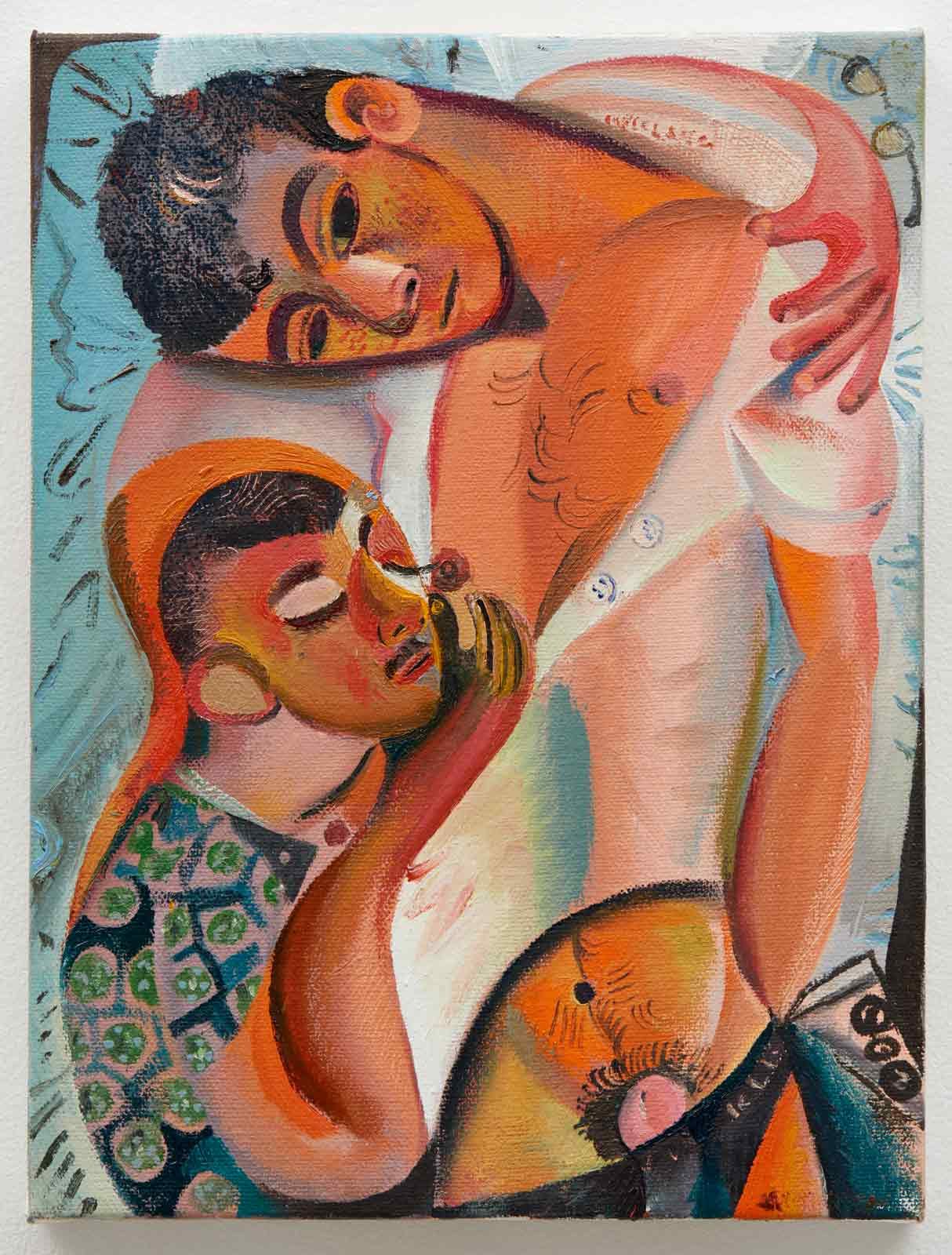

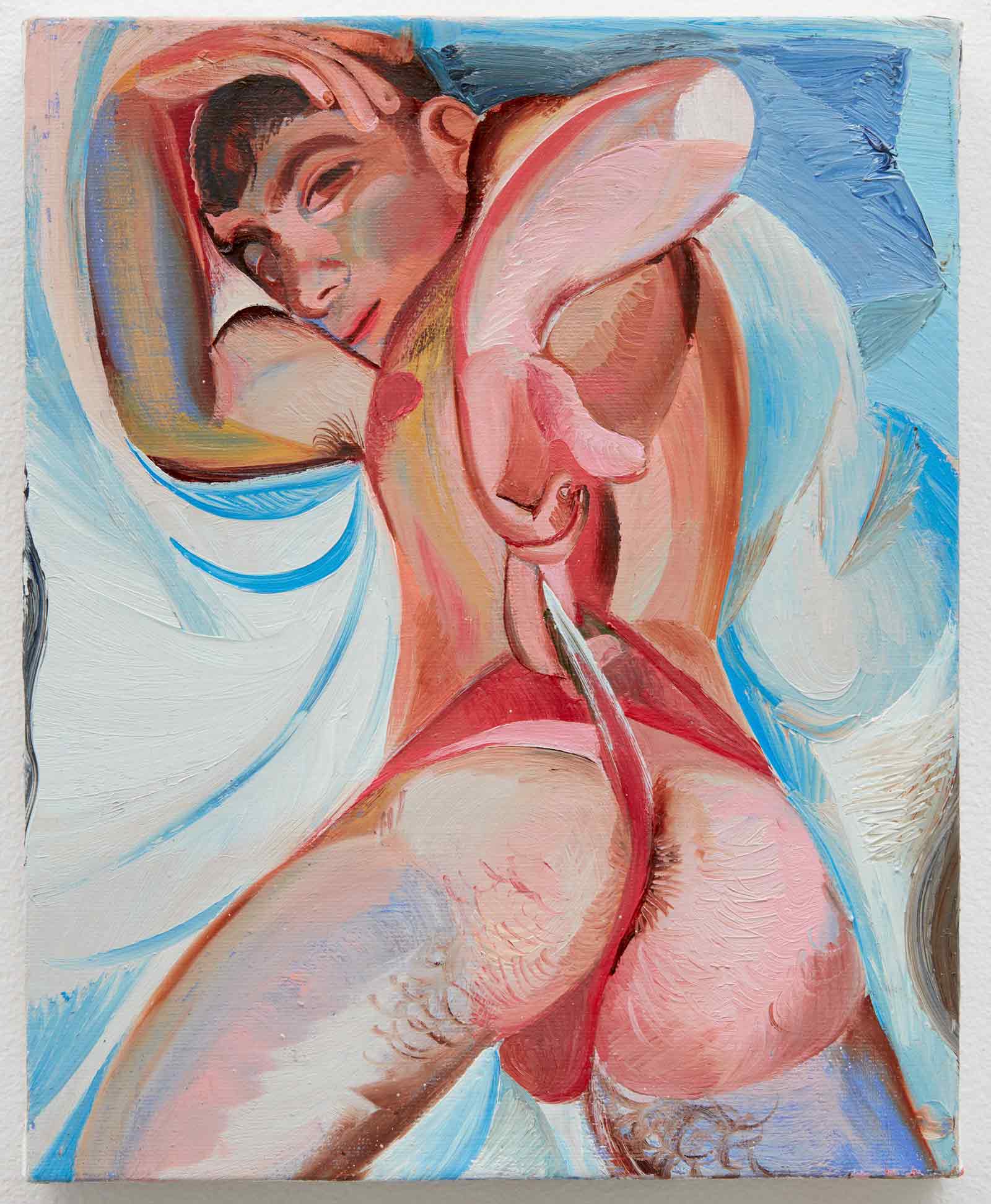

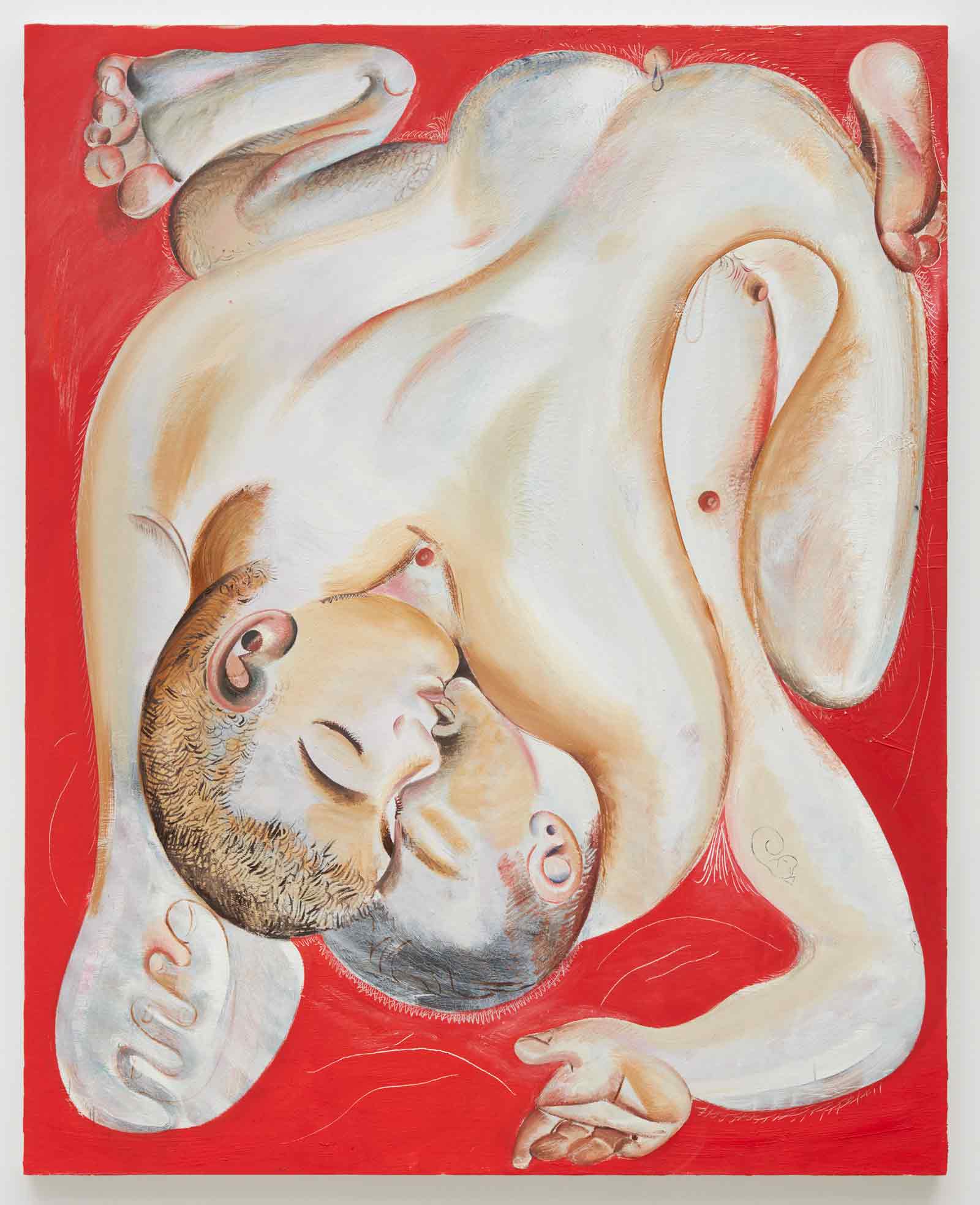

The immediacy of Fratino’s work speaks to his distinctive treatment of surfaces. In particular, he understands how skin, and the desire to touch it, is fundamental to attraction. His subjects are often shaggy and nearly iridescent with sweat; his painted surfaces exude tactility—finely scored and scraped, textured in quick, confident brushstrokes, spread thick with palette knives. And then there is his fluency of color (flesh ripens in a dark rainbow spectrum) and natural affinity for the sensual line. Lovers bend at impossible angles; limbs that don’t fit the composition taper off and disappear. Everything is pleasingly, impossibly malleable. His boys are coy, knowing, and lithe; the male odalisque, in a state of opulent undress, is a favorite leitmotif. Scenes of ecstatic coupling are tempered with an intuitive grasp of the gentle and the lyrical—a touching, if calculated, predilection for tenderness.

Born in 1993, near Annapolis, Fratino received his BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art and spent a year painting in Berlin on a Fulbright Fellowship from 2015 to 2016. When he returned stateside, he settled in New York City, working part-time as an art handler and selling tickets at the Guggenheim. It was an enchanted beginning: solo shows at Thierry Goldberg, Monya Rowe, Antoine Levi; group shows at Yossi Milo and D.C. Moore; early raves from Holland Cotter, Roberta Smith, Jerry Saltz, The New Yorker; residencies at Pioneer Works, the Artha Project, and the Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program.

Advertisement

Critics traced obvious debts to Picasso, Chagall, Léger, Bonnard, Beckmann, Hartley, Cocteau; a 2017 show in Düsseldorf, at Cabinet Printemps, paired Fratino’s drawings with lithographic reproductions of Matisse’s 1930s pen-and-ink sketches. While it’s certainly true that Fratino has inherited a modernist vocabulary—bold geometric forms, vibrant colors, abstracted but legible bodies—his sensibility and subject are distinctly contemporary. Along with Salman Toor, Doron Langberg, and Devan Shimoyama, he is at the forefront of a new queer painting that restages the rites of masculinity, privileging moments of quiet camaraderie.

The central gallery features a stunning wall of seven smaller works, mostly around 9 x 12 inches. The first, and most seductive, Invitation (2019), is a teasing boudoir portrait of a young man lying on his stomach, turned to face the viewer, plucking at his thong with a sly confidence. In Tom (2019), a man lounges serenely in tight black underwear and a plaid button-down, suspended in reverie; Me and Ray (2018) captures a moment of sexual prelude. They read like snapshots, shuffled and reshuffled in the mind’s eye before sleep.

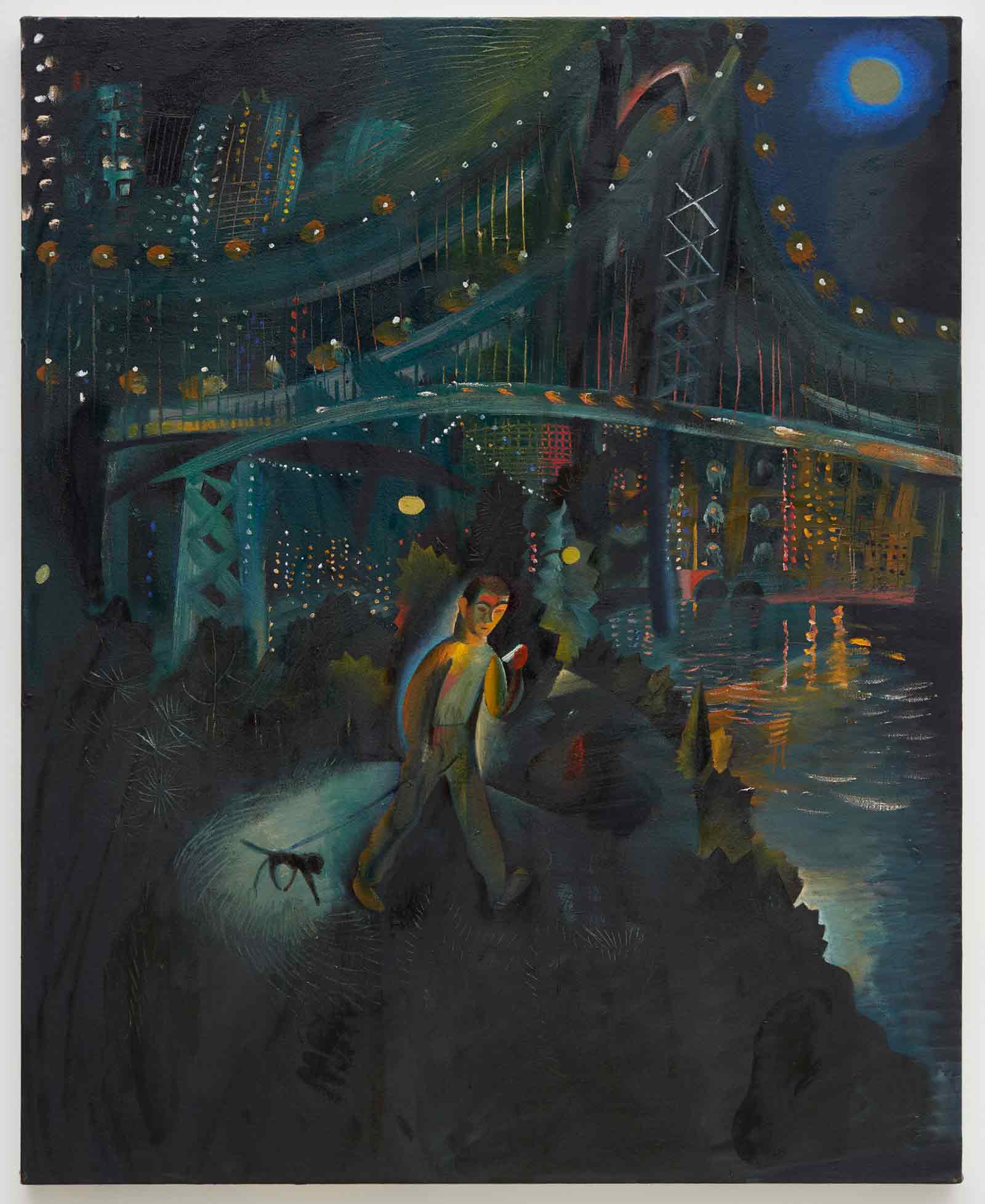

The larger works are promising, if inconsistent. The Williamsburg Bridge (2019) is dark and brooding: a gigantic lantern-jawed figure with the severe, sloped nose of an Easter Island head strides across the eponymous bridge, haloed in a penumbral, apocalyptic glow. More complicated (and satisfying) is The Manhattan Bridge (2019). A young man takes his dog for a nocturnal stroll through a riverside park, eyes locked on his smartphone. One senses that, in time, his larger works might acquire the sumptuous granularity of the smaller canvases. My Meal (2019), a richly realized still life of the artist’s kitchen table, is a touching ode to personal flotsam: a vase of flowers, sketches and photographs, envelopes covered in indecipherable notes, a meal of eggs on toast, a copy of Mario Mieli’s Towards a Gay Communism.

In 2003, Germaine Greer published The Beautiful Boy. Part glossy coffee-table smut, part art-historical treatise on desire, it remains an unusual bit of propaganda calling for the return of young men to the realm of public attraction. (The cover features a grainy black-and-white photograph of a shirtless fifteen-year-old Björn Andrésen, best known for his portrayal of Tadzio in Luchino Visconti’s 1971 screen adaptation of Death in Venice.) “Most people have accepted without question that women are treated as sex objects, viewed principally as body, with a primary duty to attract male attention,” Greer writes in her introduction. “Though this is clearly true, it is also true that women are at the same time programmed for failure in their duty of attraction, because boys do it better.”

Now an out-of-print curiosity, the book stirred up controversy upon publication. Its original publisher, Thames & Hudson, had neglected to contact Andrésen about the cover; the actor was outraged. Greer defended herself against accusations of pedophilia on national television. But the claim that beautiful boys are essential fixtures of public life is hardly radical. Western art history corroborates it: How many iterations of St. Sebastian, bound and stuck with arrows, decorate the public squares and churches of Europe? How many likenesses of Ganymede, commissioned by lords and counts? After the death of his boy favorite, Antinous, the Roman emperor Hadrian deified his beloved, erected an obelisk in his memory in Rome, and built an entire city on the eastern bank of the Nile called Antinoopolis. For the brief duration of its bloom, a boy’s beauty is meant for a universal audience: male, female, straight, gay, young, old, and everyone in between. It is democratic, accessible. So tradition goes.

Think of the kouroi of Greece and Rome, whose idealized forms survive in fragments of marble and bronze; the photography of Thomas Eakins, Wilhelm von Gloeden, George Platt Lynes, Nan Goldin, and Ren Hang; Jean-Léon Gérôme’s The Snake Charmer (circa 1879) and Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Barra (1794); Fazil Bey’s Huban-name (Book of Beautiful Boys); Caravaggio’s curiously placid ephebes, his gawking Narcissus (1597–1599); the phenomenon of wakashu in Edo-era prints; Michelangelo’s Dying Slave (1513–1516); John Singer Sargent’s profusion of male nudes; and now Fratino’s powerfully passive boys, magnetic and languorous, a marvelous beginning to this latest chapter. More than merely decorative, these figures charge the space around them with a low, erotic hum.

Advertisement

Louis Fratino’s “Come Softly to Me” is on view at Sikkema Jenkins & Co. through May 24.