One Sunday afternoon in mid-April, the Cuban artist Tania Bruguera hosted a salon in the resplendent reception rooms of the Park Avenue Armory on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Two days earlier, Bruguera’s native city of Havana had celebrated the launch of its thirteenth Bienal (April 12–May 12, 2019), which filled museums, galleries, and public spaces with exhibits, installations, and performances, official, unofficial, and banned. No work by Bruguera was included, and the artist, who comes and goes regularly between New York and Havana (where she is almost as regularly placed under arrest), announced publicly that she wouldn’t attend.

The Bienal de la Habana has had an important role in Bruguera’s career. A piece she installed in the eighteenth-century fortress and former political prison of San Carlos de la Cabaña during the seventh Bienal in 2000 was shut down by the Cuban government within a few hours of opening—enough time for a young, independent curator named Stuart Comer to experience it. For six weeks last spring, Bruguera and Comer, now at the Museum of Modern Art, brought that same installation, Untitled (Havana, 2000), to New York. “What you learn with your body, you don’t forget,” Bruguera told an interviewer about the piece, which is as vivid as a recurring dream.

After a long wait in line, you relinquish your cell phone to an attendant (to keep you from using it as a light source), and enter the pitch darkness of a wide tunnel. You pick your way towards a dim light in the distance across a floor heaped with sugar cane, your near-blindness heightening the pungency of its odor. The light turns out to be a TV screen suspended overhead, face-down, playing footage of Fidel Castro: he unbuttons his shirt to prove he’s not wearing a bulletproof vest. Then, as your eyes continue to adjust, you realize you’re not alone. Around you four naked men are standing just beyond the light. Bruguera says the work is intended not to represent the political, but to provoke political action.

*

International coverage of this year’s Bienal has focused on the repeated arrest of artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara over a performance that consists of some men running down a street with US flags. Titled “Se USA”—a pun on USA and the Spanish verb usar, the title means “it’s being used”—the work alludes to a protester arrested in 2017 for running with the Stars and Stripes in hand during Havana’s May Day parade, while its title evokes the sixty-year political cycle in which the hard line taken by a US administration against Cuba becomes a pretext for repressive measures by the Cuban government against its own people. “After Obama came to Havana, they [the government] were really scared,” a Cuban acquaintance explained to me. “They actually thought things might have to change. But then with the 2016 US election, they knew everything would stay the same.” To many, things seem not the same but much worse, as if the country had not only lost the future that seemed briefly within reach in 2015–2016, but toppled backward decades into the past. Now that Venezuela no longer offers the cheap oil on which Cuba has long depended, food and electricity rationing have been implemented, and there are fears of a return to the deprivations of the so-called Special Period in the early 1990s, when food was so scarce that every adult in the country lost an average of ten pounds.

The legal basis for the arrest of Otero and other artists is the infamous Decree 349, signed in April 2018 by Raul Castro’s long-groomed successor, Miguel Diaz-Canel. It requires that all artists exhibiting in public spaces and even in private obtain prior approval from the government. In other words, “The government gets to decide who is or isn’t an artist,” said Cuban-American artist Coco Fusco, who flew to Havana for the Bienal but was denied entry. When asked by Reuters about Otero’s third arrest, Norma Rodriguez, head of Cuba’s National Council of Visual Arts, unwittingly confirmed Fusco’s point: “As far as I know,” she replied, “he is an activist, not an artist.” In an installation for an independent gallery show that ran parallel to the Bienal, the photographer Leandro Feal set up an office where you could fill out a form and receive a badge certifying you as an art inspector, with the authority to spot violations and impose “pertinent measures.”

Feal’s installation—part of a wonderful exhibit of stories told by artists, curated by Abel González Fernández in an unmarked residence—was not shut down. And the very title of this Bienal, “The Construction of the Possible,” with its echo of Bismarck’s definition of politics, defies official distinctions between art and politics. The poet and art critic Katherine Bisquet, who kept a fierce Bienal diary for the Madrid-based website Diario de Cuba, observed that the title should really have been “Construction Within [the narrow limits of] What is Possible.” Much of the work it showcases, particularly that by Cuban artists, grapples in giddy despair with the stark dearth of political possibility.

Advertisement

The Cuban government, which regularly arrests artists and journalists, also expected to welcome a record-breaking 5.1 million tourists this year. Cuba’s leaders are well aware that cultural capital is one of their nation’s major assets. Rage, pain, and dissent were not only openly on view in this Bienal but were featured and promoted with hashtags like #CubaEsCultura. In her powerful statement, Bruguera expressed her admiration for the Bienal’s curators but explained that she was not attending because the Ministry of Culture was diverting resources to the Bienal in order to “whitewash its international image” in the wake of Decree 349. She decried the incomprehensible double standard of those who protest “art-washing” at the Whitney Biennial but “joyfully justify” the Cuban government. Her argument—that people shouldn’t travel to Cuba for the Bienal because to do so justifies the Cuban government’s human rights abuses—is one the US government has been making, in more general terms, for nearly six decades. Less than a month after the Bienal ended, the US both further restricted the free movement of its own citizens and delivered a gut punch to Cuba’s emerging entrepreneurial class by banning cruise ships and other vessels from Cuban ports and prohibiting group travel to Cuba for cultural and educational purposes.

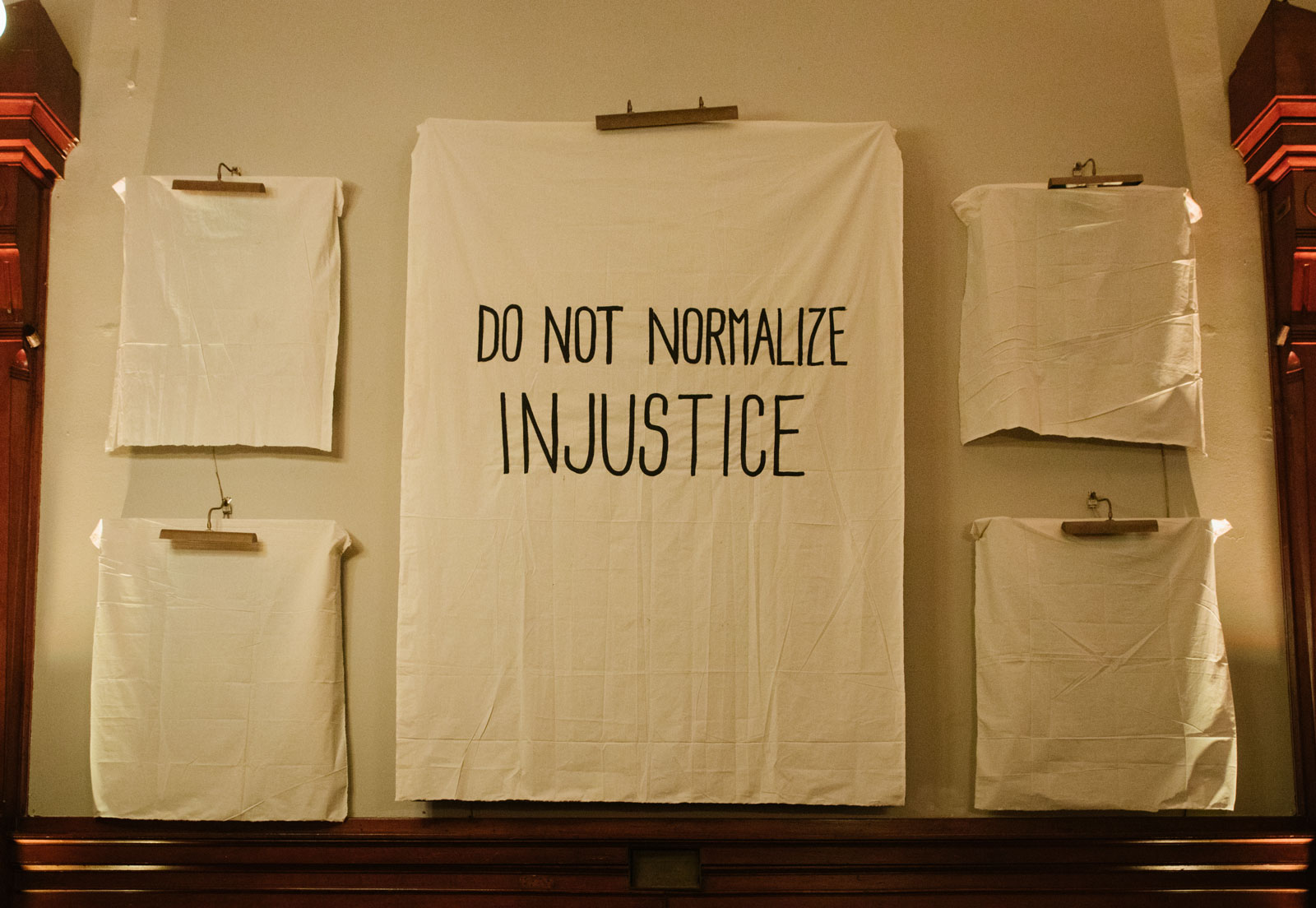

Art-washing—specifically, museums’ acceptance of funding derived from the very political and economic situations that the art they exhibit deplores—was often a topic at Bruguera’s Sunday Salon at the Armory, which took the form of a conference on museums as spaces of sanctuary, organized in response to the cruelty and racist vilification the current United States administration has inflicted on immigrants and citizens, with particular animus towards those from Latin America. Artists and activists, many undocumented, joined lawyers, educators, and Bitta Mostofi, commissioner of the New York City Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs, to discuss what museums can do. Bruguera introduced her guests then sat with the audience, without mentioning her own contribution, a short-term site-specific installation in the Armory’s broad hallway, hung with portraits of eminent nineteenth-century military men. Over the course of the afternoon, the portraits were shrouded in white drop cloths, some blank, some bearing phrases Bruguera workshopped with the public high school students in the Armory’s Youth Corps: “NORMALIZING INJUSTICE IS THE NEW OPPRESSION” said one. Another, near the exit, asked “WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BELONG?”

*

The nucleus of the thirteenth Bienal is formed by two world-class exhibits, “Beyond Utopia,” a re-reading of Cuban history, and “The Mirror of Enigma,” an irrational genealogy of Cuba’s mythic identity, both at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, where they’ll remain up through September 30. “Beyond Utopia,” curated by Delia María López Campistrous, juxtaposes works that embody moments of nationalist fervor—the wars of independence from Spain, the victory of Castro’s revolution—with others that comment on such fervor with deep, post-nationalist suspicion. The gallery that covers Cuba’s nineteenth-century revolution against Spain, for example, includes the conventional case of period weapons—swords, machetes, revolvers. But here the weapons are transparent shapes, cast in crystalline, glittering resin, and the artist who made them, Reynier Leyva Novo (born in 1983, a child of the Cuban Revolution), calls the piece “The Desire to Die for Others.”

The show’s final room, which brings us into the present, includes a shockingly evocative 1967 painting by Antonia Eiriz, who was denounced as “defeatist” by the Cuban government. Titled Naturaleza muerte (“Still Life”)—the Spanish, like its French equivalent, literally means “dead nature”—it offers, in muddy colors tinged with crimson, an empty podium, bunting hung along the front, glasses of water at the ready, no one at all behind the microphone. Looming in a corner behind is an outsized head, almost disembodied, its huge mouth gaping wide in terrible, infantile need.

Rather than following the linear progression of its companion show’s historical overview, “Mirror of Enigma,” curated by Bellas Artes director Jorge Fernández Torres, is an anarchic tour of the Cuban unconscious. One of its vehicles is a weightily ornate wooden sled made in 1994 by the now defunct art trio Los Carpinteros. Crowned with two sphinx heads and with the words “La Otra Orilla” (“The Other Side”) carved along its back, it seems intended for some occult ceremony. On a wall overlooking it is a 1996 self-portrait by María Magdalena Campos-Pons, the US-based Afro-Cuban artist who collaborated with the Bienal to organize satellite events and exhibits in her hometown of Matanzas. In the photograph, Pons has covered herself in white paint, with the words “Patria Una Trampa” (“Homeland A Trap”) etched below her collarbone. Neither of the Bellas Artes shows makes any distinction between works by artists who stayed on the island and works by those like Campos-Pons and Eiriz who left. On the gallery floor is the residue of a performance piece devised in 1976 by Ana Mendieta, who has become, posthumously, Cuba’s most famous exile artist. Black candles—placed atop a rectangle of glass in a shape like a yawning, hungry maw—were lit and burned down, their molten wax dripping off the glass’s edge, until they guttered out, leaving only cold, congealed darkness.

Advertisement

*

A gallery called El Apartamento in the residential neighborhood of Vedado offered an eclectic survey of contemporary Cuban art so full of surprises that a pair of small paintings on the top floor, hanging discreetly over a doorway in a narrow hall, almost escaped my notice. Made by Levi Orta as part of a series titled “Political Creation,” the paintings replicate the well-known bathroom self-portraits by George W. Bush. The only apparent difference is that Orta’s faceless human figure, lying prone in the tub or standing with his back turned in the shower, has darker skin. Orta made them in 2013, the same year Tania Bruguera was invited to Southern Methodist University in Dallas, where the George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum was just being inaugurated. Perhaps in response to the banal innocence Bush’s art seems to lay claim to, Bruguera told poet and art historian Roberto Tejada, then an SMU professor, that she’d like to interview Bush, and would pledge to limit the conversation to questions of artistic craft: perspective, line, brushwork, color mixing, framing. No politics at all. The idea was proposed to the former president, but to no one’s surprise, proved impossible to carry out.

Another survey of contemporary Cuban art, this one housed in the blissful neo-Baroque splendor of the 1914 Gran Teatro de la Habana, included an installation by Mabel Poblet that was among several of this Bienal’s tacit homages to Robert Smithson’s 1969 Map of Broken Glass (Atlantis), a work every collapsing building on the island seems to cite. In Poblet’s piece, circular trays of broken glass are suspended in darkness, while a film of the artist swimming, projected down onto them, creates crescent shapes on the floor, a constellation of phases of the moon. Another work in the same show, by Lidzie Alvisa, also presents a strange constellation, this time in order to ponder the fearsome two-dimensionality of celebrity. Arrayed against a black background are circular photos of the famous: Frida Kahlo, Barack Obama, José Martí, Adolf Hitler, Marilyn Monroe, Albert Einstein. Fidel Castro’s absence may be in ironic compliance with a 2016 Cuban law that forbade the erection of monuments to him.

The Cuban government seems to overlook that ban nowadays. An image seen frequently on the sides of buildings—new since I was last in Cuba two years ago—consists of three silhouettes: Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, who launched Cuba’s first war of independence from Spain in 1868, José Martí, who launched the final independence war in 1895, and Fidel Castro. Below are the words “One Single Revolution.” It’s as concise a Great Man Theory of history as anyone could wish for, and as forlorn, now that all the great men are gone.

One drawback of seeing history as the achievement of eminent men is in evidence nearby at the grandiose 1929 Capitolio building, now open to the public again during the final phases of a restoration that is rushing to finish in time for the quincentennial of the city of Havana in November. Its high, imposing front doors are decorated with a series of square bronze bas reliefs that depict scenes from Cuban history. The final one portrays Cuba’s presidents, last among them Gerardo Machado, who ruled the country from 1925 to 1933, and under whose administration the building was completed. Shortly after Machado was forced to step down, his name and face were violently gouged off, an erasure the recent renovation has carefully preserved. Machado’s face is also rubbed off the penultimate bas relief, where he’s shown with Calvin Coolidge, the first US president to visit Cuba, who’s faceless, too.

On a dusty side street not far from the Romeo y Julieta tobacco factory, in a gallery marked only by its open front door, a photo exhibit proposes a different approach, and its impossible gesture of erasure and revelation was one of the defining moments of the 2019 Bienal. No artist’s name was visible, but one of the walls bore a title: Un día feliz (“A Happy Day”). A large dog sits next to a caned rocking chair. Krushchev stands with a dead duck in his hands, another dead duck suspended in mid-air next to him. A baseball flies towards a batter from an empty pitcher’s mound. And in what seems a tacit salute to Antonia Eiriz’s Naturaleza muerta, one of the gallery walls is hung with photos of podiums, decades of podiums, some with gigantic crowds beneath, one bearing the VE RI TAS seal of Harvard University, many with photographers who aim their lenses at a point behind the microphones where no one stands.

Reynier Leyva Novo, the fertile-minded young artist who created the series—other photos in it are displayed at El Apartamento, with his name attached—has digitally altered iconic images by Lee Lockwood, Alberto Korda, and others, to eliminate Fidel Castro, or, you might say, to de-platform him. What’s left is a blank wall cross-hatched with dappled sunlight, an empty field with low mountains in the distance, the open ocean. And also, maybe, air to breathe, space for the imagination, silence to hear yourself think: a future.

*

For Havana locals, the focal point of the past three Bienales has been outdoors along the city’s seaside promenade, the Malecón, where the curator Juan Delgado Calzadilla orchestrates a wild array of sculptures and installations. When all the galleries were closed for May Day, my partner, Nathaniel Wice, and I joined José Miguel Sánchez Gómez, a science-fiction writer better known as Yoss, and his wife Dania Rubio Miranda, to stroll among the bands of selfie-takers enjoying the art and spectacular weather.

Yoss’s sci-fi has been nominated for the Philip K. Dick award and translated into more than a dozen languages, and he and Dania were just back from launching one of his novels in Russia. The fourth of his books to appear in English will be published here next June, but Yoss won’t be at that launch. For him, as for most other Cuban nationals, a US visa has become almost impossible. To apply, he’d have to fly to a third country and cool his heels there indefinitely on the very small chance of being approved.

Nathaniel and I once visited Yoss’s mother’s house, where he still sometimes writes in his old bedroom, and saw a nearly four-foot sea turtle shell mounted on the wall. “Some friends and I hunted it during the Special Period,” he told us. “Food for a month!” Now, on the Malecón, we came upon another immense turtle, rocking face-up on its shell, immobilized, its sharp claws flailing in the air, its head a sinister red clown—a sculpture by Roberto Fabelo, a winner of Cuba’s National Arts Award. While her boyfriend took photos, a woman dressed in white planted a long kiss on the grinning mouth, her dark hair whipping in the wind. The piece is fabricated in resin-coated polyfoam that seems as if it might float, and another group of passers-by was loudly and merrily assessing its feasibility as a balsa, the makeshift rafts people use to escape the island.

Other things we saw along the Malecón were less eye-catching than Fabelo’s turtle, but no less arresting. That includes several buildings reduced to dramatic shards by Hurricane Irma, which destroyed more than 14,000 Cuban homes and killed ten people in September of 2017. One oceanfront building, still standing but clearly abandoned, seemed, from across the street, weirdly incrusted. Closer inspection revealed that artist Elio Jesús had wrought a sea-change of his own upon its street-level arches by inserting countless slips of rolled-up white paper into their holes and cracks, bringing to mind the prayers worshippers tuck into chinks of Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall. But with its air of having been barnacled by long submersion, what Jesús’s piece reminded me of most was a calmly genocidal statement cited by Cuban-American historian Louis Pérez Jr., which was read into the Congressional Record in 1903 by Senator Francis G. Newlands: “Cuba would be desirable if for half an hour she could be sunk into the sea and then emerge after all her inhabitants had perished.”

The most elegiac work in the outdoor show could hardly have been simpler. It consisted of a jumble of three or four dozen beat-up chairs and settees—what you’d get if you asked all your friends and relatives to loan you whatever they had on hand—assembled at one end of the Malecón, facing the sea and the curve of the Havana skyline. A few were reupholstered in white fabric, silkscreened with details of a dark-skinned body: a shoulder here, an elbow there. A rusting TV antenna rose among them, sticking out at an angle from a block of concrete. The piece suggested simplicity, community, shared presence: a peaceful assembly of people come together for a purpose. By Jorge Otero, the work is called “7:30 p.m.”—an invitation to gather and watch the sun set over the rising waters.

The Havana Biennial was ongoing from April 12 to May 12, 2019.