Ségou, Mali—We agreed that I would visit Fanta’s family in the bush where they were herding cows. Two nights before my arrival, her sons told me not to come. The militia that has been massacring ethnic Fulani herders had reached their part of Mali; if the militiamen had spotted me, they would have followed me right to the encampment. So Fanta took a westbound bus from the nearest town, and I took an eastbound bus from Bamako, and we convened halfway, in the ancient city of Ségou, on the porch of a friend of a friend.

It was our first meeting since 2013, when I had herded cattle with Fanta’s family for a yearlong cycle of transhumance, the seasonal movement of livestock, in order to research a book. Back then, Fanta had adopted me the way one would long-lost kin, or maybe a refugee; six years later, she greeted me as if we had parted only a week before. Fanta’s cornrows were mostly white now, her teeth mostly gone. We shared a mango. We exchanged family news. We talked about rain and the state of pasture and cattle: this was promising to be a wet year, a good year. Fanta’s sentences unspooled like song.

Then I asked about the violence and her story faltered, words frayed.

“Oh, Anna,” Fanta said. A pause.“Just as I was boarding the bus to come here I saw the militia with my very own eyes.” Another pause. “I am so worried.”

Then she was silent for a long time. She drew her sequined shawl over her face.

*

What do we talk about when we talk about ethnic cleansing? In Bamako I sat on plastic woven mats in the miserable camps for internally displaced persons. Some of the people I met had been in the camps for a year, some had arrived only a week earlier. Regardless of when they had been displaced, all of their accounts were a terse stutter, a shocked attempt to describe the indescribable.

In the Faladié IDP camp, in huts built with sticks and donated tarps on top of a refuse field behind a livestock market, men spoke into the air noxious with rot and sewage:

“They killed that boy’s grandmother while she was carrying him on her back.”

“That child, he has bullet scars on his arm and ankle.”

“People’s uncles, mothers, aunts died. Everybody ran like crazy.”

In the Niamana IDP camp, women preparing donated rice under a donated tarp said over cooking fires barely hotter than the scorch of June sun:

“They shot dead my father-in-law and my son and we ran.”

“We left one old woman behind. She was so old she couldn’t move at all. Her son said, ‘I cannot leave my mother,’ so he stayed with her. They burned them both alive.”

“Almost all of us here are widows.”

There was no progression to their meager stories, no chronology. They had to be pieced together pragmatically, inferred from context, from the taking of turns in conversation. Even more so from the pauses, from the giving up on words. They were awkward, like stick-figure drawings. Terrible in their bare-boned sparseness.

*

There is, of course, an articulate documentation of iniquity. Rooted in the colonization of Africa and in the Europeans’ arbitrary carving-up of the continent’s borders during the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, it was set in motion with the Arab Spring. In 2012, in looted pickup trucks chock-full of artillery and explosives and rifles plundered from the vast, abandoned caches of the fallen Muammar Qaddafi, Tuareg separatists crossed the Sahara from Libya, swept into Mali’s desert north, and proclaimed the creation of an independent state, Azawad: the Land of Transhumance. The world did not recognize Azawad, but Islamist fundamentalists—Arab, Berber, Fulani, Tuareg—saw it as a convenient staging-post for a jihad from which a new caliphate would rise in the Maghreb. Within weeks, they hijacked the rebellion. They flew black flags of al-Qaeda over Timbuktu and Gao. They axed down centuries-old shrines they deemed idolatrous. They flogged, amputated, jailed, stoned, beheaded, raped.

The West intervened and the rebellion splintered and spread in response; one of the new militias was a fundamentalist group led by the Fulani cleric Amadou Koufa, who called upon his nomadic disciples to join a new jihad to rebuild the nineteenth-century Fulani kingdom that stretched from Timbuktu to Ségou, the powerful Macina Empire. The group attacked men believed to have collaborated with the Malian army; burned several local government buildings, and brought down a communication tower. Most attacks crossed ethnic lines; ethnic Bambara and Dogon villagers formed small self-defense units and staged retaliatory raids. A new outlet for an old grievance: in West Africa, sedentary farming people and pastoralists have fought over resources for centuries, but climate change has made the battle more urgent. Mali has been growing progressively hotter and drier since the 1960s, and cyclical dry spells now wham the Sahel in rapid-fire succession.

Advertisement

In 2016, a paramilitary group made up primarily of ethnic Dogon hunters formed in central Mali, with the stated purpose of protecting settled communities against Fulani jihadists. In 2018, the hunter militia began systemic attacks on Fulani herders, both those who live in villages and the ones who chase rain in the Inner Niger Delta without establishing domiciles. It is here, to the south of the battlefields where United Nations’ peacekeepers are fighting against a seven-year-old insurgency, that Fanta’s family has for generations tended its cattle for five months of the year in sweet hippo grass that still shoots its spongy blades out of the seasonal swales of the flooding Bani River.

In the hamlet of Koumaga, where Fanta would sometimes stop to rest on the way to barter milk for millet and rice in Bambara villages farther south, the paramilitaries shot dead twenty-three Fulani men and boys in their homes in front of their mothers, daughters, sisters, wives.

In the village of Meou, a two-hours’ walk north of Koumaga, they killed twelve Fulani men and boys. A couple of hours to the east, they executed eleven Fulani men who were driving cattle to the animal market in Sofara.

In the village of Dankoussa, halfway between Meou and Sofara, they led nine Fulani men into a mosque and shot them there. In Somena, where Fanta would go for honey and gossip, they shot all the boys and men, dragged their bodies through the neatly swept streets, and threw them down the village well.

I remember the men of Somena. In 2013, one of them, Fanta’s distant cousin, lent me an enamel bowl to carry a honeycomb I bought in the village to our bush encampment. I remember how he raised a long finger to invite me to wait until he salvaged a lid from some other vessel in his household, how he wiped it on his sleeve before placing it carefully on the bowl to protect the honey from the dust on the unpaved path I would take, how we both smiled at his thoughtfulness. How many people, how many men in Somena? I asked Fanta.

“All the men in Somena they put in that well,” Fanta responded. “There are not even chickens in Somena now. Only empty houses.” Later, I found a website with a list of seventeen names. The number makes a difference, and yet, in a dreadful way, it doesn’t.

In the geographic middle of the country, the violence spread. On New Year’s Day of this year, the militia killed thirty-seven Fulani children, women, and men in Koulogon, a village farther west, close to the border with Burkina Faso. In April, it massacred 160 Fulani people in Ogossagou, in the same area; some were infants; some were burned alive. The UN peacekeeping force, embroiled in the anti-separatist mission up north, has been unable to stop the mass killing in central Mali—as has Mali’s rickety government, which collapsed in April. Raids against nomadic Fulani encampments are almost weekly now. The lists of people who squat in the twelve Fulani IDP camps that circle Bamako—lists forever incomplete because new families arrive all the time—catalog some of them: Milma, Anacada, Yolo, Boni, Tena, Temogole.

In Djenné, a medieval trading post in the heart of the floodlands, a friend of mine got married this spring. He is a settled Fulani, a city man. He sent me photos of his bride, a slender young woman with a beautiful new tattoo around her mouth, and of her younger sister, whom he had adopted as custom dictates. To my note of congratulations, he responded: “Thanks. Yes, three people from their clan have been killed, two uncles and one brother, and their village Sirabougou is almost empty. Only old women remain.”

The thorny acacia scrim that once rang with the cowboys’ ululations and the lowing of cattle has emptied of people and cows. The price of meat has tripled.

*

“Is the language of silence that of the refusal of language or, to the contrary, the language of the memory of the first word?” asks the French-Egyptian writer Edmond Jabès. Can there perhaps be another kind: a refusal of having to articulate the unutterable?

In the Dialacorobougou IDP camp in June, where three hundred Fulani herders squatted in unfinished cinderblock houses, an elder in an embroidered wool boubou shook my hand and held it. His narrow palm had milked thousands of cows, driven thousands of stakes into the ground to tether his cattle. His name was Boucary Hamidou Barry. His cattle were gone. In the camps, everyone’s cattle were gone, abandoned when the militias attacked; the Fulani here have no economy to return to in the bush. He told me all this still holding my hand, to make sure I stayed, to make sure I heard him when he said: “I am the oldest person here and I have never in my life heard of such barbaric violence as what we have seen. There are no words for it.”

Advertisement

Maybe there ought not be words for it, I thought. Maybe it is immoral to have the words for it, maybe having the words means belittling the essential horror of the thing.

“An end to the granting of names,” writes Paul Celan.

*

I first met Fanta in the fens of the flooded Inner Niger Delta. I walked with her, taking the annular route her ancestors had established during the nineteenth-century Macina Empire, or possibly earlier. By December, after the rice and millet harvest, her family would set up camp on one a low rise in the Inner Delta, one of the hundreds of pastoralist families whose encampments, perfect circles of mats, hearths, and cattle, would poke out of the water like salvages from a shipwrecked ark. For the next five or six months, as the water receded, the floodlands would smell like sour milk. Then, at first frog’s croak, typically in late spring, the nomads would move on, giving ethnic Bambara and Dogon farmers a turn with the land. Fanta’s family would walk southeast, toward Burkina Faso, where they would spend summer and fall. Then, after harvest, they would walk back to the floodlands. A small familiar orbit in the oceanic tracts of the Sahel: not homelessness, simply a vastly magnified idea of home, about forty miles in diameter. The nomads were always leaving—and they were always returning.

Last year, after the attacks in Koumaga and Somena, Fanta’s family abandoned their usual route and drove their cattle toward sunset. Now they are among the more than a quarter of a million Malians displaced by conflict. Their most recent camp is about a hundred miles away from their historic pastures, in a part of Mali where they had never walked before.

“Now we feel like we are just running around the world,” Fanta said. “This time next year, who knows if we will be anywhere at all?”

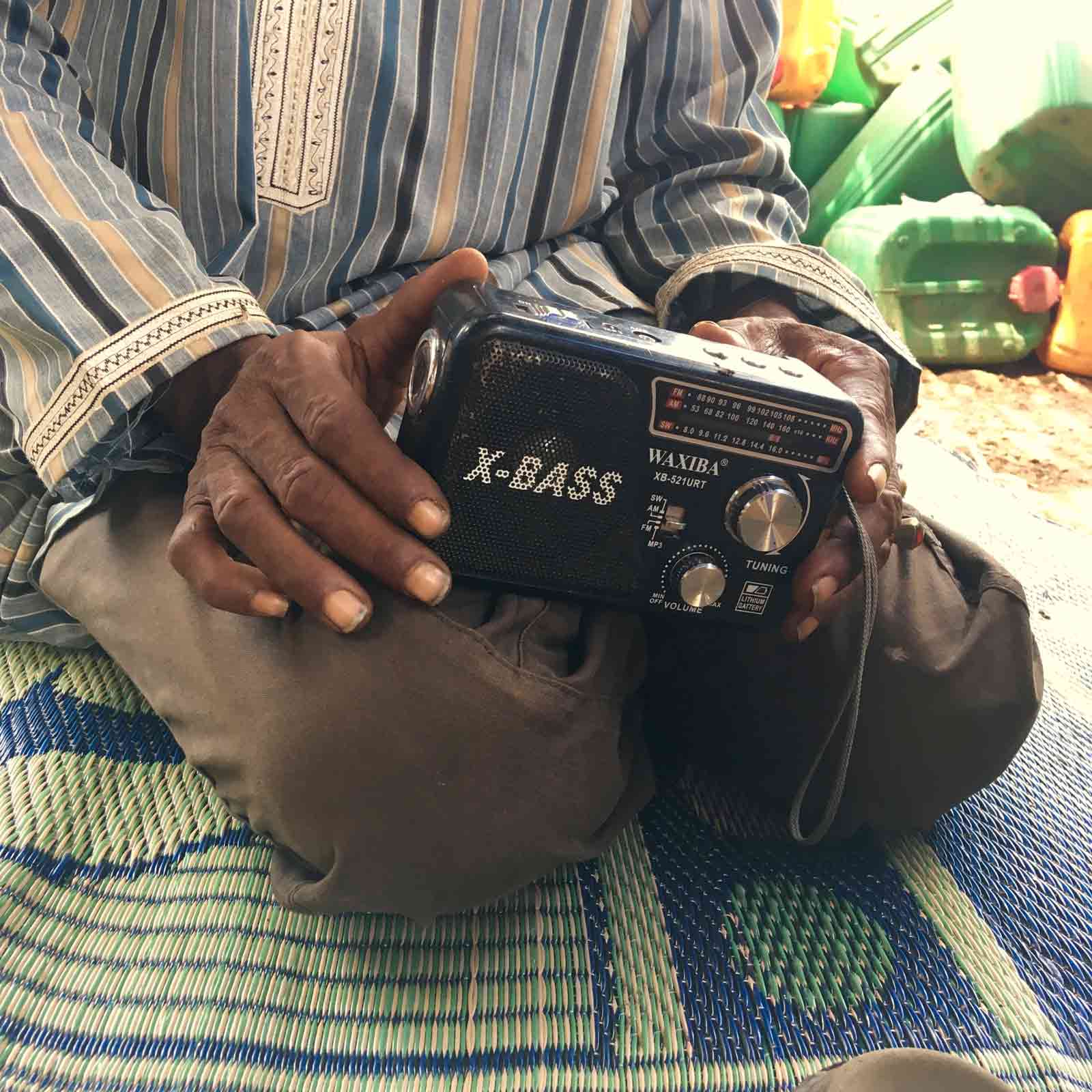

On a mat in the Faladié IDP camp, a cowless herder named Gari Dialló placed a transistor radio in his lap, tuned it to a Fulani-language music station, the song’s beat iambic, go on, go on, go on, go on, go on, setting pace for a cattle drive that is no more.

*

Each time I hear of a new pogrom of a Fulani settlement I call Mali. I was in New Mexico when I learned of the Ogossagou massacre. It took me two days to reach anyone to ascertain that my loved ones were okay. Between frantic calls, I thought of the multitudes around the globe who also, day after day, are trying to learn if their families are okay.

What words can describe such a global heartsink? When we codify mass violence and ignominy into language, how do we avoid creating shorthand for suffering greater than a heart should fathom? What is the language for a seventy-four-year-old woman, birdboned and gracile, crying from war-grief behind her shawl on a borrowed porch in Ségou?

On this porch, on a Monday in June, two women sat eating a mango and weeping. The clay plateau around the city was still dry but the red fields were tilled, broken open to the low pearl of cloud. Briefly, it did rain, staccato pellets on the new tin corduroy of slanted awnings. Time was running out: it was mid-afternoon, and soon Fanta would have to catch a bus back to the town near her family’s encampment. Our last words to each other were scant.

“Today we meet, but after we go our way and you go yours, only God knows when we will lay eyes on one another again,” Fanta told me.

“I love you,” I replied.

Then we sat wordless. And then it was time to go.