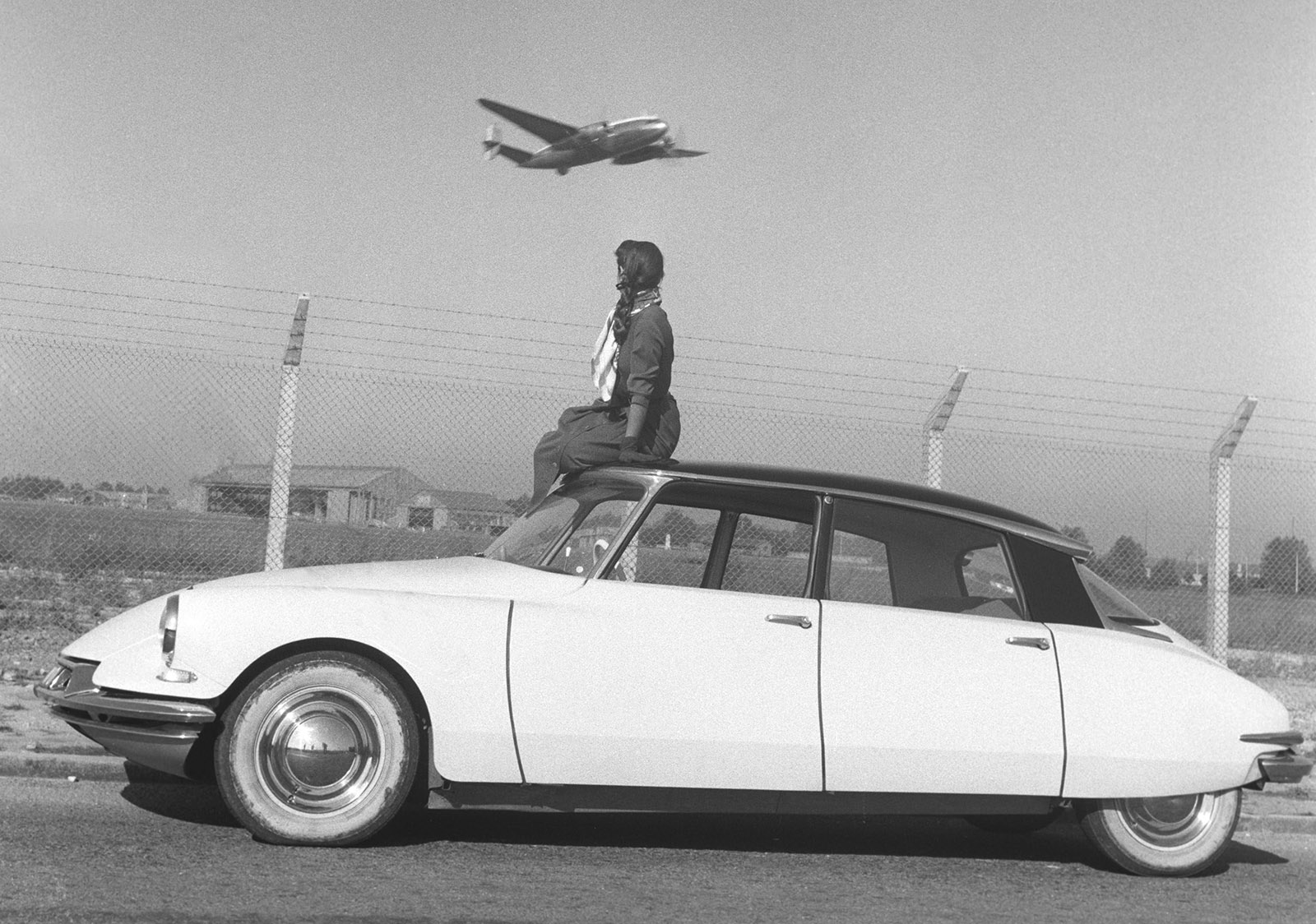

In the exhibition halls, the car on show is explored with an intense, amorous studiousness: it is the great tactile phase of discovery, the moment when visual wonder is about to receive the reasoned assault of touch (for touch is the most demystifying of all senses, unlike sight, which is the most magical). The bodywork, the lines of union are touched, the upholstery palpated, the seats tried, the doors caressed, the cushions fondled; before the wheel, one pretends to drive with one’s whole body. The object here is totally prostituted, appropriated: originating from the heaven of Metropolis, the Goddess is in a quarter of an hour mediatized, actualizing through this exorcism the very essence of petit-bourgeois advancement.

—Roland Barthes, “Citroën DS” in Mythologies (1957)

The French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan drove a Citroën DS. What else? This car, Barthes tells us, was a truly magical object, a perfect fetish, the essence of freedom, movement, and power. And yet, cars are also a sign of our insignificance, like the problem of traffic jams, parking lots, and statistical casualties. The DS—or Déesse (a wordplay on the initials that justified Barthes’s calling the car his Goddess)—seemed to promise the ability to drive with one’s whole body—the broken promise of all technology. We can almost touch the future. Almost.

Lacan understood the seductive appeal. Read anything about Lacan’s life and you will find it punctuated by stories about cars and driving. These are certainly apocryphal stories told about him that have circulated among psychoanalysts and appear in biographies or anecdotal commentary, but cars were also clearly a thorough-going texture in his thought. Almost every case study Lacan mentions—and these are quite rare in the twenty-eight years of seminars that form the spine of his work—somehow or other ends up involving a car, driving, and roadways.

Of course, we English speakers hear another pun in drive: “drive” as a verb, something we do, and “drive” as a noun, something that acts upon us. Even if the equivalence doesn’t exactly work out in French—conduire, pulsion—Lacan nevertheless fought against the English translation of Freud’s Trieb into “instinct”—drive, he said, is the only translation to militate against such stupid American Darwinism. But it isn’t the pun that interests me so much as the fact that this car business makes Lacan seem a little more pedestrian, while still allowing for a mythology, slightly off-center, away from the great man. After all, isn’t this just a boy and his toy?

Not for Lacan, who placed the car at the very center of his own analysis. Lacan was in a six-year psychoanalysis with Rudolph Löwenstein, who had himself been analyzed by Freud, and later emigrated to New York. It was not a fruitful encounter, with Lacan attempting to take the driving seat:

To illustrate the situation between him and Löwenstein, Lacan told Catherine Millot of an incident that occurred at the time. One day he was driving his little car through a tunnel when a truck came at him head-on from the opposite direction. He decided to keep going, and the truck gave way. He told Löwenstein what had happened, hoping to make him see the truth of their transferential relationship. But he got no answer. And the mortal struggle… ended in open conflict.

Lacan was only granted membership to the Psychoanalytic Society of Paris in 1938 as a bargaining chip to admit another psychoanalyst fleeing Germany, Heinz Hartmann, who was a friend of Löwenstein’s. Since this was against the advice of his analyst, who felt Lacan needed more work, the institute decided to make Lacan’s membership conditional upon continuing in his analysis. Instead, he promptly left it. We now have a number of bitter letters in which we see Löwenstein openly denouncing Lacan—a terrible breach of confidentiality, no less of ethics. Strange fact: when Lacan was eventually thrown out of the International Psychoanalytical Association for his use of variable length sessions (and not the standard forty-five to fifty minutes), Lacan declared the analyst presiding over the commission to be his mortal enemy. This analyst was later killed in a car crash.

Lacan had two families, and his two youngest daughters were born, to their different mothers, just eight months apart. Even after he left his first wife, Malou Blondin-Lacan, their three children did not know of his other wife, Sylvia Bataille, and their daughter, Judith, for quite some time. There was, however, a fateful encounter at a crosswalk. Lacan’s son and youngest daughter recognized their father in his car, but not the woman next to him, nor the little girl sitting in the back seat. When they called out and ran toward him, he drove off. Only subsequently would they put two and two together. When, later, Lacan’s eldest daughter, Caroline, was killed by a drunk driver, her funeral was one of the few occasions that the families were forced to confront one another’s existence.

Advertisement

Lacan’s son-in-law, Jacques-Alain Miller, wrote a biographical text on Lacan and speaks about his intolerance of red lights, how he ran them all the time. Even when Lacan was merely a passenger, if you refused to run a red light, he would get out of the car, walk through the crossing, and have you pick him up on the other side. Apparently, this behavior was a source of great anxiety for his daughter, who had to devise ways to avoid stopping when driving.

Lacan himself drove fast. Once, he took Martin Heidegger and his wife, Elfride, on a day trip to Chartres to visit the cathedral. Though Heidegger was a hero of his, Lacan continued to drive at his characteristic high speed despite Elfride’s frantic protestations. As the story goes, Lacan was completely silent on the long drive back as he pressed harder and harder on the gas pedal.

Catherine Millot, Lacan’s patient and lover, in her autobiographical book, Life with Lacan, wrote of how he used to drive:

[H]is head forward, gripping the steering wheel, treating obstacles with contempt, as one of my women friends noted, never slowing down even for a red light—and as for observing the right of way… well, let’s not go there. The first time, on the autoroute, travelling at some 120mph, I had a fit of the giggles which I suppressed only with difficulty. But even if I’d burst out laughing, he’d never have noticed; he was concentrating too hard… there was no point in imploring him to slow down. Once, his stepdaughter Laurence had come up with a bright idea: she asked him to drive more slowly so that she could “look at the countryside.” He told her: “Just pay more attention.”

Millot and Miller both consider Lacan’s way of driving as part of his ethical stance. One had to follow one’s desire and not give way to inhibitions or norms. If one had to stop, make it a choice; do not yield to an anonymous law or the whims of the other’s demand. His driving ethic is even used to explain his rapacious consumption of luxury goods—Lacan had quite an art collection, and was known for his sartorial extravagance, from custom-made suits in unusual textiles, to furs, and shoes in rare skins. It may even explain why “obstinate” is the last word attributed to Lacan before his death. This is always the story that one encounters about Lacan, part of the mythology of the courageous, disobedient, relentless man.

*

If one looks at how Lacan speaks about cars throughout his work, it is not just this mythological tale of man v. law, but something more, and more extraordinary: a real love affair with the car, a passion of the strangest of contours. If Freud had a fascinating and symptomatic relation to trains—the place that he first encountered his mother naked and thus the scene of a certain transgressive, incestuous excitement; the conveyance on which he found he felt guilty for surpassing his father in the scope of his travels; and for which he developed something of a phobia, only partially resolved by his self-analysis—for Lacan, it was certainly cars. Lacan joked that while a psychoanalytic institute, thinking of itself as a kind of driving school, might offer one a driver’s license, we shouldn’t mistake this for knowing how to fix a car or “supervise” car construction. Psychoanalysts might be a kind of driving instructor but they should not mistake themselves for auto-mechanics.

The first reference to cars in Lacan’s teaching appears in his second seminar, given in 1954–1955. In a supervision group, a patient was discussed who had dreamed of a helpless baby, like a turtle on its back. Lacan said to the psychoanalyst, “The child is the subject. There is no doubt about it.” The patient went on to have another dream: of swimming in a sea with special characteristics that also made it the analyst’s couch, the analyst’s car cushions, and, of course, the mother (mère, mer). While the association of the traditional psychoanalytic setting (lying on a couch, with the analyst seated behind) with being driven around in a car by one’s parents is quite common, the dream, Lacan says, isn’t really about the dependency of children. Rather, it is about the repetition of a question we helplessly ask throughout our lives: Am I a legitimate child? “Aren’t I, after all, your child, you the analyst?” To whom do I belong?

Advertisement

A car then reappears the following year in an important seminar evaluating the question of psychosis in psychoanalysis. Lacan is trying to show how foreign the world becomes for someone having a psychotic breakdown:

If he encounters a red car in the street—a car is not a natural object—it’s not for nothing, he will say, that it went past at that very moment. Let us inquire into this delusional intuition. The car has a meaning, but the subject is very often incapable of saying what it is. Is it favorable? Is it threatening? Surely there is some reason for the car’s being there.

The red car becomes the paradigmatic object of paranoia. Like the robin redbreast, it can become a malevolent sign, making us, in effect, see red. In the face of questions not easily answered—why is this car there? Why am I here?—the need to find an answer tips in the direction of aggression.

In fact, in his earlier text “Aggressiveness in Psychoanalysis,” written in 1948, the car is already linked to potential feelings of hostility:

These phantasmagorias crop up constantly in dreams, especially when an analysis appears to reflect off the backdrop of the most archaic fixations. I will mention here a dream recounted by one of my patients, whose aggressive drives manifested themselves in obsessive fantasies. In the dream he saw himself in a car, with the woman with whom he was having a rather difficult love affair, being pursued by a flying fish whose balloon-like body was so transparent that one could see the horizontal level of liquid it contained: an image of vesical persecution of great anatomical clarity.

The man is trying to escape something in his car and that object is the image of a urinary bladder. Cars, the dream seems to say, are like human organs externalized—this is the prosthetic purpose of technology and even weaponry, indeed the “bodywork” of which Barthes spoke. Lacan imagines that the eternal struggle of humans with one another and with their bodies might find resolution in service to the machine, where “psychotechnics” will give us no choice but to be “race-car drivers and guards for regulating power stations.”

Lacan’s car theme then reaches a pitch of delirium. He begins to imagine the human being in an Eden in reverse, a kind of hell of mechanical creatures without any form of regulation:

Think of these little automobiles that you see at fairs going round at full tilt out in an open space, where the principal amusement is to bump into the others. If these dodg’em cars give so much pleasure, it is because bumping into one another must be something fundamental in the human being. What would happen if a certain number of little machines like those I describe were put onto the track. Each one being unified and regulated by the sight of another, it is not mathematically impossible to imagine that we would end up with all the little machines accumulated in the center of the track, blocked in a conglomeration the size of which would only be limited by the external resistance of the panelwork. A collision, everything smashed to a pulp.

This isn’t just the traffic jam of all traffic jams, it is an image of humans bashed, bumped, and eventually ground to destruction. Yet this dystopian image of infinite piled-up dodgem cars does not prevent Lacan from going on to fantasize about the smooth, vast, efficiency of highways that he calls an “original reality,” a marked “stage of history” comparable to the building of Roman roads, which left traces that are “practically irremovable.” Highways provide order, cut through space, distribute and signpost life, connect us to one another. But what if there aren’t highways?

Lacan makes a wild leap: without them, he says, we might become completely psychotic, forced to take any number of small roads on which we will inevitably get lost: “where the signifier isn’t functioning, it starts speaking on its own, at the edge of the highway.” The street signs will start speaking to us—in other words, auditory hallucinations. Psychotic fantasies follow a trail of meaning precisely because, for the sufferer, meaning has fallen to pieces.

The end of this car and highway story in this seminar is quite beautiful, tracing the way the sentence “Thou art the one who will follow me” might be heard. It could be a persecutory command. But it could also be a gentle invitation to the unknown. You ask the other to follow you; to be, in effect, a psychoanalyst—say anything, everything, and off we go. The person who welcomes your words, Lacan says, is someone you can really fall in love with. That can change your direction. Get you out of the horrific pile-up of interpersonal persecutions. The psychoanalyst could save us from auto-destruction.

In a seminar titled Desire and Its Interpretation, Lacan describes a case from the British psychoanalyst Ella Freeman Sharpe. It begins with an important dream that involves a cave with a kind of hood:

My mind, he continues, has gone to the hood again and I am remembering the first car I was ever in. (But at that time of course it was not called a car but a motor, because the subject is fairly old.) Well! The hood of this motor was one of its most obvious features. It was strapped back when not in use. The inside of it was lined with scarlet. And he continues: The peak of speed for that car was about sixty. (He speaks about this car as if he were speaking about the life of a car, as if it were human.) I remember I was sick in that car, and that reminds me of the time I had to urinate into a paper bag when I was in a railway train as a child. Still I think of the hood.

Ella Freeman Sharpe is quick to interpret the patient’s standard Oedipal fantasy (the car representing his desire for his mother, the cave with a hood is her vagina), following up with another of the patient’s associations—a fear of his car’s breaking down and stopping the motorcade of the King and Queen. Lacan, however, jumps on this interpretation as hasty and banal: “What on the contrary seems to me to be very striking, is precisely the function of the car… The subject is in a car, and far from separating anything by this stopping… everything stops, he stops the others… in a single car which envelops them like the hood of his car.” The patient wants to stop all speech and to keep everyone else at their peak of speed, while he stays sheltered in his car. Speech is exposing, speech makes the others less omnipotent, speech slows us down.

The patient finally comes in and tells Sharpe that he wanted his car this morning, and even though he didn’t need it, he became quite angry that the garage mechanic had not finished fixing it. The analyst greets this desire like the dove that flies to Noah’s ark, and Lacan says, he is in “complete” agreement with her:

She understands the importance of that, namely what is present in the life of a subject as desire properly speaking, desire being characterized by its non-motivated character—he has no need of this car; the fact that he declares his desire to her, that it is the first time that she hears such a discourse, is something which presents itself as unreasonable in the discourse of the subject.

The patient wants his car, he likes his car, he loves it, in fact. He speaks about it as if it were alive. The patient’s father had died of cancer when he was quite young and Sharpe says that they had finally gotten to a place where he imagined his father not only as alive, but as speaking. But what the father said was terrifying: “Robert must take my place.” Lacan interprets this statement as a demand: be where I am, where I am dying. He neurotically complied—paralyzed, car-sick, broken down. Wanting the car, indeed wanting it fixed in a hurry, this miraculous sign of desire, finally takes him past the mortifying paternal commandment.

The most explicit moment when Lacan theorized the car appears in his seminar on Transference in 1960–1961. He says, point blank, that one’s relation to the car is the hinge between the ideal-ego (the super-ego, as moral demands and narcissistic images) and the ego-ideal (the singular traits of our parents’ desire that we can identify with), and the analyst must be decidedly on the side of the latter. If the analyst takes up the super-ego position, it will be “an ideal ego in the same sense as one says that a car is an ideal car: it is not an ideal of the car, nor the dream of the car when it is all alone in the garage, it is a really good and solid car.” But there is no “really good and solid car.” We are not here, as psychoanalysts, to comment on the car’s build as good, solid, normal, or not. Better that we dream of the car. Or desire that the patient dream of the car.

Lacan was very invested in the difference between the ideal-ego and the ego-ideal in Freud’s conception of the origin of the psyche and the development of civilization, especially the problem of what Freud called group or mass psychology. The ego-ideal is full of wishes that are historic and specific, while the super-ego represses these libidinal ties and homogenizes individuals into an imaginary group identity—like thinking oneself to be a “really good and solid” Christian or Conservative or Brexiteer:

The ideal ego is the son and heir at the wheel of his little sports’ car. And with that he is going to show you a bit of the countryside. He is going to play the smart alec. He is going to indulge his taste for taking risks, which is not a bad thing, his love of sport, as they say. And everything is going to consist in knowing what meaning he gives to this word sport, whether sport cannot also be defying the rules, I am not simply saying the rules of the road, but also those of safety. In any case, this indeed is the register in which he will have to show himself as being better than the others, even if this consists in saying that they are going a bit far. That is what the ideal ego is.

Fighting Daddy at the wheel of one’s “sports’ car” to prove who is the better man is different from trying to obtain an object of love with a car, or loving the car. This is the “side-door” everyone is looking to get out of when it comes to the father (or, say, a demagogic leader). We seek an exit from our enmeshment with authority. Psychoanalysis wants to do so by subverting this game of the ideal-car with the car-ideal, the car as a vehicle for love and desire, not its repression.

A little later in the same seminar, in an aside, Lacan discusses a man he met (not in psychoanalysis) who opened up to him concerning matters of the heart. He says this man was a an “extremely rich man.” One day, he “knocked down somebody on the street with the bumper of his big car. Even though he always drove very carefully.” The woman he knocked over was very pretty; she received his apologies, his attempts to pay damages, and an offer of a date all rather coldly.

“In short, in the measure that the difficulty became greater of gaining access to this miraculously encountered object, the notion grew in his mind,” Lacan explained. “He told himself that there was here a real asset. And it was for this very reason that all of this led him into marriage.” If love is supposed to go beyond narcissistic images of what’s valuable, this is not the case for this man who accumulated “goods and merits.” This woman he met by miracle was an ideal-car, which is why, after marrying her, acquiring her, he wanted to keep her in his safe along with all the jewels that he bought for her. After some time, the woman ran off with a rather poor engineer.

In one of the rare, lengthy cases discussed by Lacan in his seminar on Anxiety of 1961–1962, there is, once again, a car. Lacan tells the story of a woman who was in analysis with him and finds herself at a distance from her husband, whom she liked to complain about for always being around:

So here she is now, speaking about her state. She speaks about it, for a change, with peculiar precision, which brings out the fact that tumescence is not a man’s privilege. This woman, whose sexuality is quite normal, bears witness to what occurs for her if, when she is driving, for example, an alert flashes up for a moving entity that makes her say to herself something along the lines of “God, a car!” Well, inexplicably, she notices the existence of a vaginal swelling.

He claims that when a woman is close to this kind of orgasmic pleasure, she is closer to the world—“more true and more real.” What she desires is what there is, even if it’s merely a car driving by.

For this woman in analysis, he says, the car was about the meaningfulness of the world-as-such, rather than any particular meaning, especially one that is in danger of adding to a fiction of the self, of tangling one up there. Also, the patient says, this is happening because she can come and tell her analyst about it all. This is where she had come to in her work with Lacan: the car as a signal, not of anxiety, but of a desire that is practically empty, but infinite, and so infinitely mobile.

*

The very last mention of cars in Lacan occurred during the events of May 1968. Lacan moved his seminar to Vincennes, where students had set-up an experimental university. There is some discrepancy with respect to what he exactly said (all his seminars are transcribed from recordings), whether exclaiming that he saw thirty-six cars, or thirty-six police cars, on his drive there. Either way, he implored the students not to mistake the force of these cars—their display of will—for actual power; though he admitted that they do give a robust illusion that someone is in charge. From 1948 to 1968, we have come full circle, the car finally invoking a dystopian image of the world.

Lacan tried to teach the students how psychoanalysis thinks of power differently—it is not force as power, he said, but the power of language, of an address that can leave a mark. But the students kept interrupting him, heckling that he should stop talking and get out on the streets. By the end of the encounter, Lacan was quite fed-up. They seemed to want a master despite their protests, he said to them, and if that’s what they wanted, they would surely get it. He had come to tell them how psychoanalysis was a radical practice—that it might help them—but they didn’t want to hear anything but their own complaints.

Lacan didn’t think you could revolt your way out of oppression. Psychoanalysis creates a change in discourse which, he believed, was the only way to change something in reality or, at the very least, to change our relationship to reality. He told the students to go write something interesting, because this would have the most longlasting effects. Easy to imagine, they scoffed at what seemed to them like a conservative old man.

Lacan was sixty-seven in 1968. He would go on to teach and write for another thirteen years, but he never mentioned cars publicly again.

And after the car disappeared, in his last seminars, Lacan’s thinking changed direction. We are left with the conundrum of the “drive” without its vehicle, which is perhaps why we find only talk of roads, paths, maps, surfaces, and topology. Lacan’s late work was certainly less enchanted with the mitigating capacity of language and desire on human hostilities; nor did he believe any longer in the power of the highway system, which, like a good father, could help set things right or give a little order to the world.

It is as if, post-1968, Lacan gave up on collective ideals because he suspected that they all produce the same problematic paranoid group effects, from fervor for leaders and mass hysteria, to racism and other hostilities rooted in difference. Following the political disasters and disappointments of the 1960s and 1970s, many disciples of Lacan predicted the appearance of more forms of psychosis in society.

If early psychoanalysis showed us anything, it was that individual solutions could be found, but these took time. We shouldn’t be in such a hurry to smash up what exists; it will only open the door to something worse, Lacan warned his audience. Psychoanalysis, through Lacan’s methodology, would stop taking apart the ideal-ego in an effort to try to find the nice, benign ego-ideal; instead, it must attempt to create something completely new, without any guarantee that it could do so. Sublimation we might call this.

So can the car subvert its fetishistic value, its broken promise, its phantasmagoric tendency toward hostility and haste? The possibility was always there, for Lacan. The car as a plea to the other: follow me, let’s go! The car as something to dream about, to use to escape one’s family, or any group identity, for what it does to our capacity to feel alive. The car as the sign of the life of speech, a sign of what can move us. Through Lacan’s elaborate twenty-year love affair with the car, we watch its meaning for him vigorously empty itself into life—so that it becomes almost just desire itself. But with its final appearance during the events following May 1968, the car reverts from a dream of liberation and bliss to being a problematic ideal, a will-to-power whose destructive mission is difficult to put the brakes on.

I believe this Lacan, and yet I miss the other Lacan and his sense of the car for where, and how, it could transport us. Which one is the true story? The Lacan who detested stop-lights? Or Lacan the race-car driver? The Lacan who loved the car? Or a Lacan whose car-ideal was always under threat? A Lacan of the disappearing car?

We often write or think about what we wish for, not necessarily what is—even though what is determines, in ways we often can’t see, what we wish. Perhaps Lacan wanted something other than his own relentlessness—for himself, his loved ones, his colleagues, his patients, maybe the whole world. Psychoanalysis, he said repeatedly at the end of its life, would probably disappear from the world. It was too fragile for it.