One hundred years ago this month, the Shakespeare and Company bookshop opened its doors for the first time in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. As we celebrate the centennial, the popular story of the shop’s founding is sure to be retold. The origin story of the shop often goes as follows: during the 1920s, Sylvia Beach, a devoted enthusiast for the literary genius of her time, decided to set up shop a few steps from the Luxembourg Gardens. From there, Beach’s biography is often framed as a Cinderella story of Modernism. When James Joyce asked her, an amateur bookseller, to publish Ulysses, and she rose to the occasion, she underwent a transformation from an anonymous shopkeeper into an internationally famous figure. Beach then provided a home for expatriates like Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald who came to Paris during “Les Années Folles,” France’s version of the Roaring Twenties. Beach has thus been memorialized as the “midwife to Modernism.”

“Certain people are meant to be midwives—not mothers of invention. Sylvia was one,” wrote Noël Riley Fitch, author of Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation (1983), in the most recent introduction to a collection of Beach’s letters. Yet to characterize Beach as merely a “midwife” and to remember her primarily for bringing into being the work of Great Men is to misrepresent her and the everyday work of her shop. Revisiting the story behind Shakespeare and Company’s creation reveals that its roots lie in early twentieth-century feminist activism and, in particular, Beach’s own deep-rooted conviction that women had a right to an intellectual life.

*

When Sylvia Beach moved to Paris in 1916, it was a realization of a lifelong fascination. She had considered Paris “the spot in the world” ever since she moved to the French capital with her family, which relocated there from New Jersey in 1902 when Sylvia’s father became an associate pastor at the American Church in Paris. One of his main tasks was to run cultural seminars for American students living in the Latin Quarter, and through this work, Sylvia was introduced to the city. In her memoir, published in 1959, she writes about encountering, through her father’s work, not only opera singers and classical musicians but also figures like Loie Fuller, a famous dancer at the Moulin Rouge nightclub and a pioneer of modern dance. The Paris that Sylvia encountered was eccentric and avant-garde, and she deeply wished to know it. By the time the family had to return to the United States so that her father could take up a position at Princeton, she was already determined to return to Paris one day.

Back in the United States, Sylvia became increasingly interested in feminist ideas. This culminated in the 1910s, when Sylvia, along with her two sisters and her mother, joined the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, later known as the National Woman’s Party. As a part of her work for the organization, Sylvia and her sister Cyprian lobbied officials in New York, reporting back to the national headquarters Washington, D.C. At the same time, Sylvia grew increasingly troubled at the social constraints imposed on women. In private letters, she revealed how distressed she was that her friends considered marriage to be their only option in life; in one case, she wrote to one of them, Marion Peter, a lifelong connection, about her concerns regarding another friend who “seem[ed] to think there’s only one thing a woman can do, and that is to get married.”

Sylvia’s vision for her own future was clear: she would write and participate in the literary world. She moved to Europe in 1916 to pursue this ambition. She started first in Spain, where she researched Spanish feminist movements and wrote an article about her findings. Her sister Holly helped her in her attempts to find a publisher for the piece, but in spite of the coordinated efforts of the Beach sisters, Sylvia met with rejection. A year later, she moved to Paris, where she sought to continue her work in the women’s movement. This time, as World War I ground on, she hoped to gain entry to the Finley Unit of the Red Cross as a translator. Sylvia wrote home to her mother that the Finley Unit, which was made up exclusively of American women, was a “triumph for feminism.”

Although that hope went unrealized, since the Unit was full and no longer in need of recruits, she eventually joined another section of the Red Cross, the Balkan Commission, in 1918. This work took her to Serbia, where she used her contacts in the Red Cross to seek out Serbian feminists. “We are busy all day and of (sic) an evening,” she wrote in a letter back home, “take a Serbian lesson with the young lady of the house, which isn’t so bad when you consider that she is out-&-out ONE OF US where the Emancipation of the Sex is concerned.”

Advertisement

Despite these connections, Sylvia ultimately found this time in Serbia frustrating. She was irked by the way some of the officers around her joked about the desolation the war had brought to Serbia, and she was angered by the way women were shut out of the important decision-making processes. “So frequently the handling could be improved upon but as every speck of it is done by men—no women control anything whatsoever in it—they have no one to blame but themselves when it ALL goes wrong,” Sylvia wrote home to one of her sisters.

Back in Paris in 1918, Beach’s work with the anti-war French feminist Hélène Brion provided a template for how Sylvia could fuse her literary and feminist visions. So radical were Brion’s politics that she was arrested in 1917 for the crime of “defeatism” in her pacifist-feminist writing. Forthright in her own defense, she opened her statement at trial by declaring: “It is because of my feminism that I am an enemy of war.” To be a feminist, she argued, was to be an enemy of all forms of oppression, injustice, and violence; it was this, not pacifism, she insisted, that determined her views. The court ruled that Brion was indeed a “subversive,” but gave her a suspended sentence.

Beach attended her friend’s trial and took in the media circus, which clarified for her how feminist agitation was seen as a destabilizing and threatening force to national morale during the war. Even before Brion was arrested for “defeatist” writing, the French police had been tailing her and keeping a file on her activities. In historian Suzanne Grayzel’s account of the trial, she notes that the French police recorded Brion as a “woman of slovenly behavior, hysterical in word and pen, who stimulates the ardor of her syndicalist comrades throughout the territory.” Clearly, any overlap between feminist and socialist movements was considered especially dangerous.

Nevertheless, Brion continued to publish her subversive tracts in the journal La Lutte féministe (“The Feminist Struggle”). Literature was central to Brion’s mission, as she editorialized: “To guide us in our enormous task, we have the writings of feminists, men and women, who have come before us.” Beach worked with Brion to develop lists of English-language women writers whom La Lutte féministe should encourage its readers to take up. It was precisely by reading women’s literature, Beach and Brion believed, that women would be empowered to realize their intellectual potential. Reading was thus both emancipatory act and feminist practice.

The struggle went on after the war, when women in Paris were still discouraged from participating in the world of books. This gendered approach to literary culture was not new in the postwar era—notions of the dangers of women’s reading had circulated throughout France throughout the entire nineteenth century. Women were considered uniquely susceptible to a phenomenon called “Bovarysme”—the view that, after Gustave Flaubert’s heroine in his 1856 novel Madame Bovary, books could corrupt a woman and untether them from their traditional roles. Even doctors weighed in, providing medical explanations of “Bovarysme,” some arguing that since women a “lower brain-weight” than men, they were physically not constituted for intellectual pursuits. When women spent hours and hours reading, these medical experts averred, they were entering into an unnatural state and were prone to losing their minds. Women should avoid reading, others advised, as the overstimulation of their brains could lead to dysfunction of the reproductive organs: a woman who read too frequently would find it impossible to conceive.

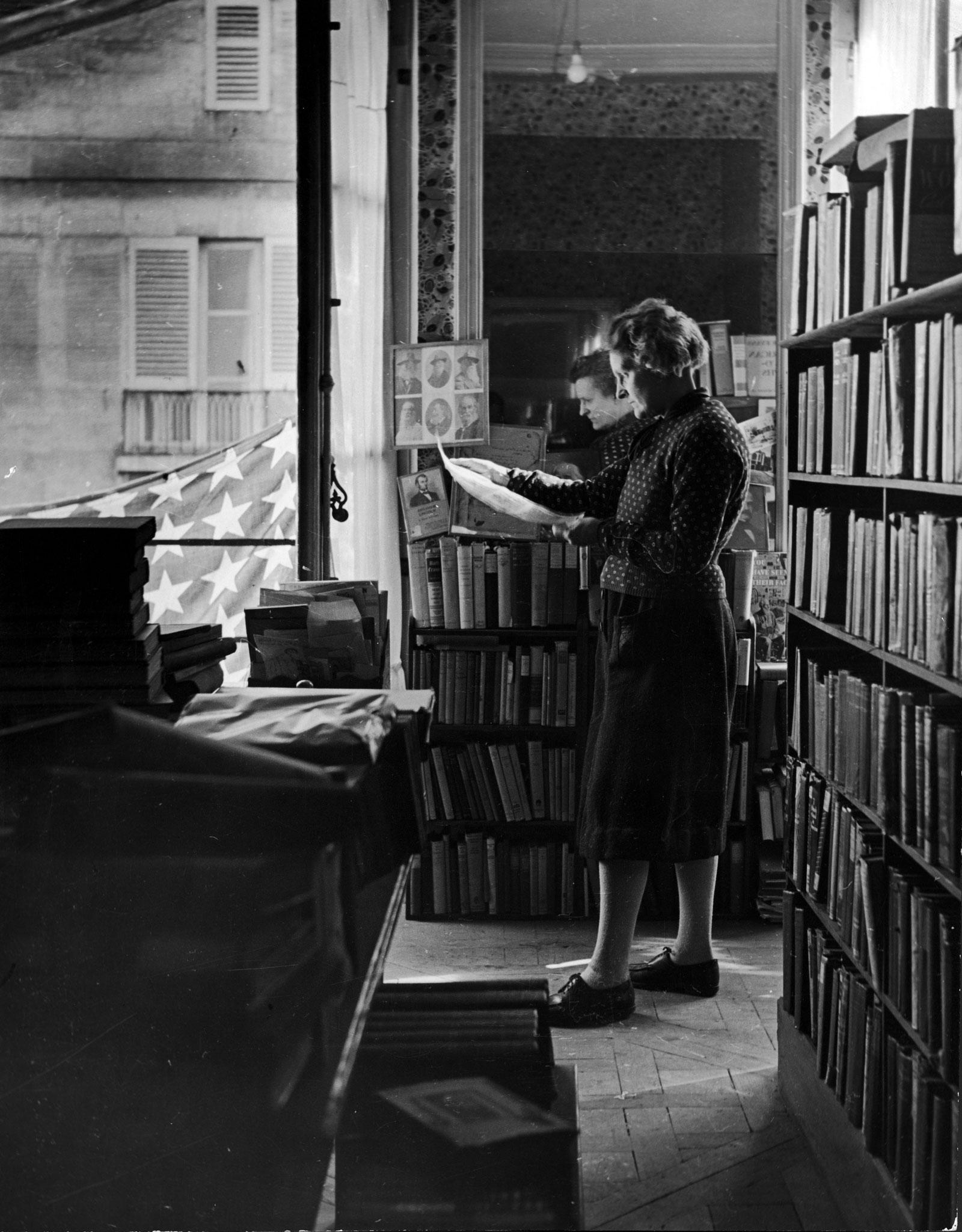

Shortly after arriving in Paris, Beach sought out La Maison des Amis des Livres (The House of Friends of Books), run by Adrienne Monnier, one of the only woman booksellers in twentieth-century France. The listing, as well as all of the advertising for La Maison des Amis des Livres, referred to the proprietor as “A. Monnier.” This was a calculated tactic for Monnier, to hide that the “A” stood for “Adrienne.”

In 1938, Monnier addressed the different ways women and men were taught to interact with books in a radio piece titled, “Les Amies des Livres” (The female friends of books):

Women are asked to take care of their persons and their homes above all; they are praised for devoting themselves to housework and it is not considered proper for them to become lost in books, whether these books be frivolous or serious… But recognize with me that the men who reproach women for not liking books are poorly founded in their criticism since it is they themselves who keep women in that state of mind.

Sharing insights gleaned as a bookseller, Monnier related how, even in the mid-twentieth century, women were still being socialized to avoid the world of books. As Virginia Woolf would so famously argue in “A Room of One’s Own,” published a decade after Sylvia opened Shakespeare and Company, women need encouragement and cultural space to read and write in order to have the same opportunities as men to contribute to society. Woolf questioned how different the world would be if women were considered intellectual and creative and were given the space to fulfill that potential.

Advertisement

In 1919, Beach exemplified her own version of this notion by opening Shakespeare and Company and running it in accordance with the feminist principles she had acquired. From the start, Shakespeare and Company was built on Sylvia’s connections with other women. Her mother, Eleanor, wired Sylvia money from her savings to start her business; Monnier helped Sylvia find a location for the shop, and then helped her build her base of French readers.

Beach and Monnier became romantically involved. When, in 1922, Beach moved Shakespeare and Company to the building facing La Maison des Amis des Livres on the rue de l’Odéon, Monnier wrote that a new, more inclusive literary world in Paris—“Odéonia,” as Monnier named it—had begun.

The structure of “the lending library” echoed many of the themes of Beach’s feminist work for La Lutte féministe that the purpose of the journal was to provide “an intellectual life” for “women and for working-class people.” The journal was experimental in nature and was created not to be purchased, but to be borrowed for a small fee and passed on—a pricing policy that intended to make the material accessible to all, especially working-class women. On a list of “borrowers” in the first edition of La Lutte féministe, which was entirely handwritten, Beach’s careful English-style script stands out, identifying her as the only non-French participant in the project.

In much the same way, Shakespeare and Company was, from the start, more a lending library than a store. This system made available imported English-language books that would otherwise have been prohibitively expensive. Books in general were considered a luxury item in interwar France. Once the cost of importing them was added on, English-language books became even more unattainable. As Beach wrote in her memoir: “Our moderns, particularly when pounds and dollars were translated into francs, were luxuries the French and my Left Bankers were not able to afford. That is why I was interested in my lending library. So I got everything I liked myself, to share with others in Paris.”

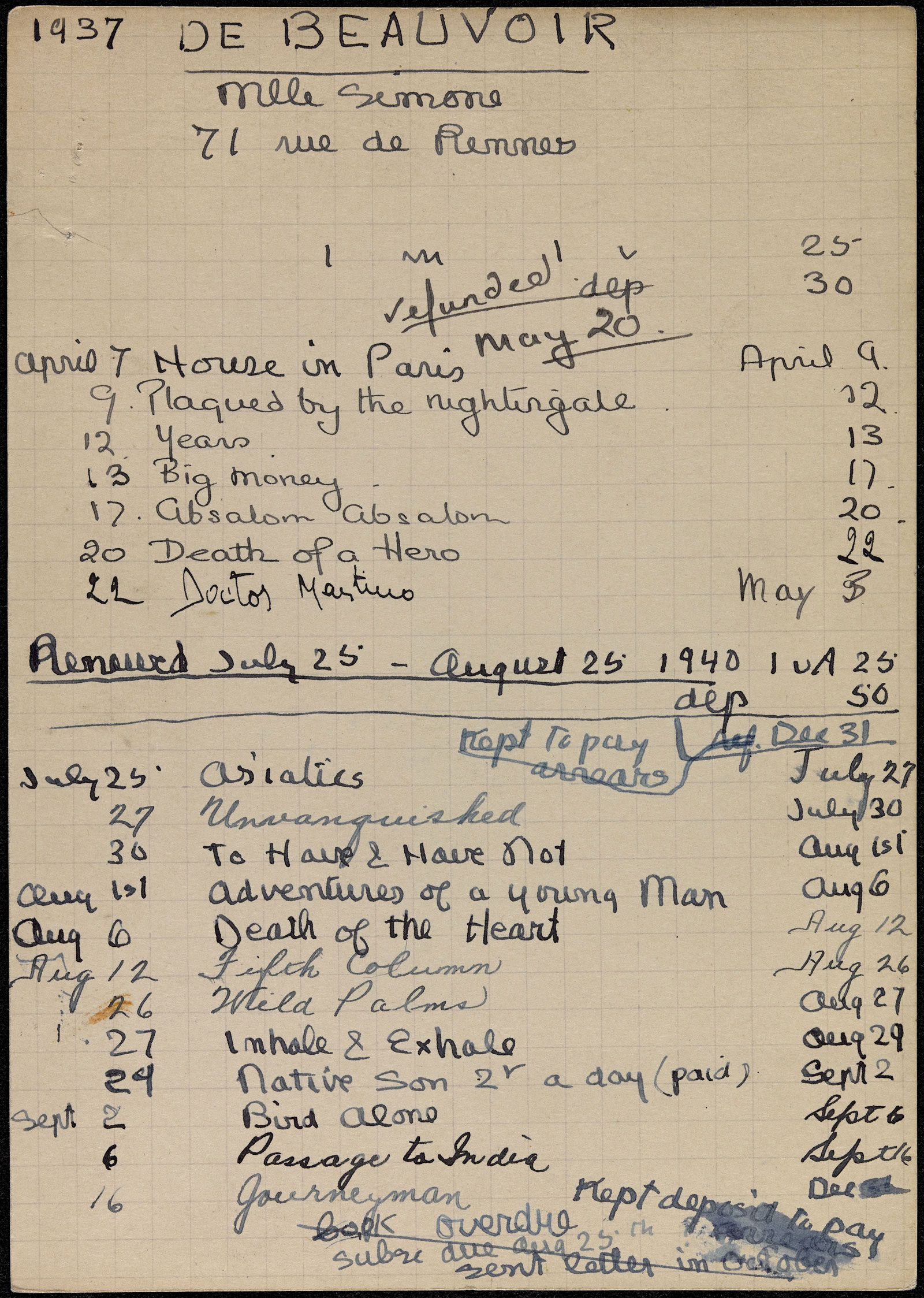

Word of Beach’s objective to “share with Paris” traveled fast. “In those days there was no money to buy books,” Ernest Hemingway recalled in A Moveable Feast, his memoir of living in Paris as a struggling writer in the 1920s. “I borrowed books from the rental library of Shakespeare and Company, which was the library and bookstore of Sylvia Beach.” The bookshop’s library cards, which are collected in Princeton University’s archives, attest to the enthusiastic response that Beach’s project elicited from women living in Paris. As her records reveal, the majority of her readers were women and they came from every neighborhood of Paris, from the richest boulevards of the Right Bank, to the most modest student and immigrant communities of the Left.

*

The 1930s ushered in a decade of precarious financial circumstances for Beach, as many Americans returned home to the United States, and the global financial crisis reached her shop, but with the help of her community of readers, who organized events to raise money, she persevered. Even after the German army occupied Paris in 1940, and, as Beach recalled in her memoir, “day and night, people streamed through the rue de l’Odéon” to flee from Paris, the shop kept running. She refused to leave, and she refused to capitulate to the Nazis’ regulations and race laws. While neighboring theaters and cafés turned away Jewish Parisians, Sylvia’s assistant, Françoise Bernheim, who was Jewish, continued to work at Shakespeare and Company. Sylvia accompanied Bernheim everywhere and avoided places her assistant would be barred from.

Even when, in 1941, Beach declined to sell a Nazi officer a first edition of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake that was on display in her window and he threatened to return later and “confiscate” her books, Beach did not waver. Instead, she and the women who assisted her achieved something astonishing: they made the entire shop disappear in protest. “My friends and I carried all the books and all the photographs upstairs, mostly in clothes baskets; and all the furniture. We even removed the electric-light fixtures. I had a carpenter take down the shelves. Within two hours, not a single thing was to be seen in the shop, and a house painter had painted out the name, Shakespeare and Company, on the front of 12 rue de l’Odéon.” There was an unoccupied apartment in Sylvia’s building, which the concierge opened for her to store Shakespeare and Company’s stock. The thoroughness of the operation ensured that her precious collection would never be seized by the Germans.

Sylvia was later arrested, and brought to an internment camp built in the Bois de Boulogne, where one of the park zoos had been made into a makeshift camp for American women. Released after six months’ detention there, she went into hiding at Le Foyer des Etudiantes, a hostel run by a friend of hers for female students in Paris. Beach survived the war, but Shakespeare and Company never reopened on the Rue de l’Odéon. She continued to live in the apartment she had kept above Shakespeare and Company until her death and worked on her memoir of the shop.

*

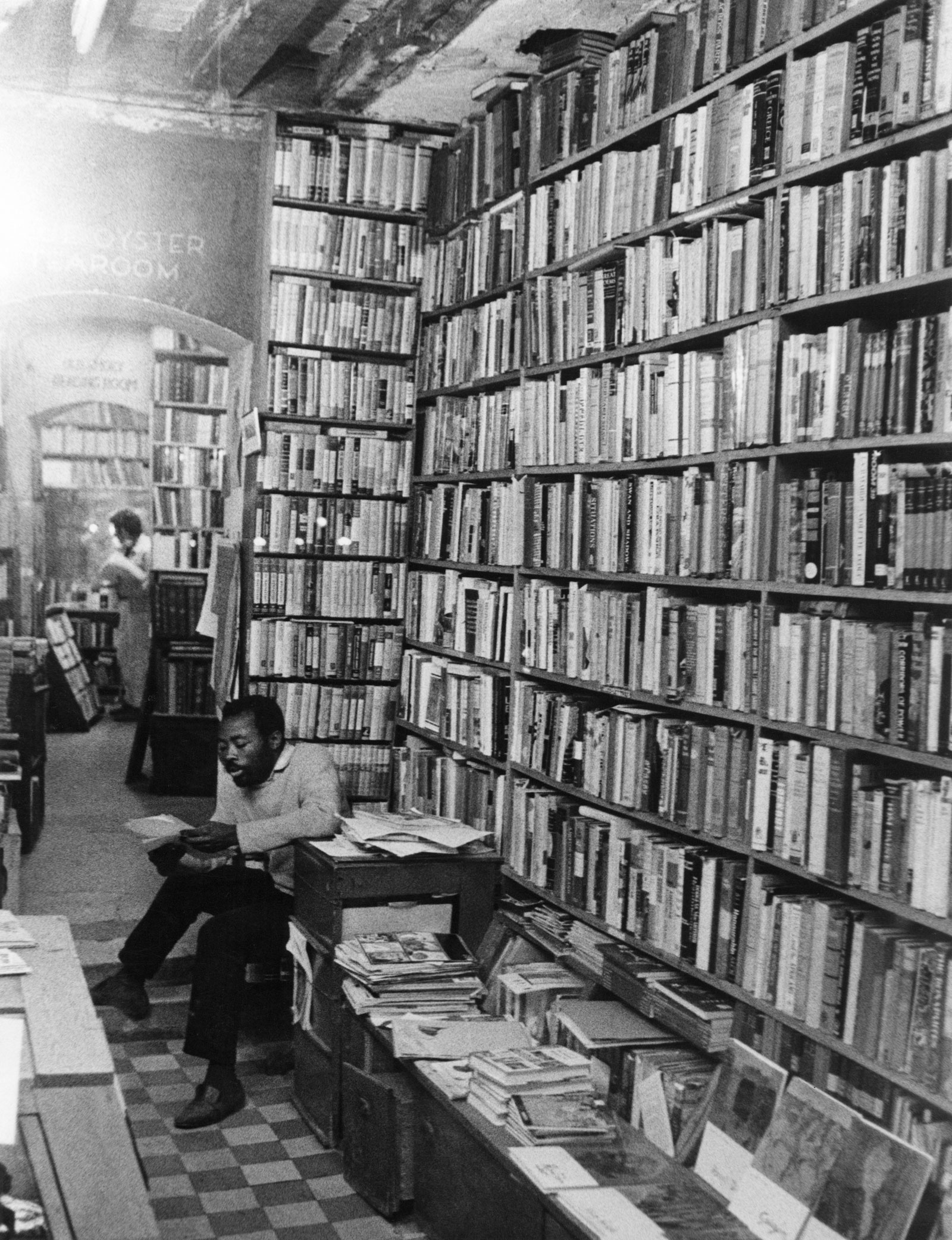

It was thanks to another American, George Whitman, that the literary community Beach fought so hard to preserve lives on in Paris today. On August 14, 1951, Whitman opened a small bookshop, Le Mistral, in the historic, yet run-down, Latin Quarter of Paris. Le Mistral, too, became a gathering point for artists from the start. Some, like Richard Wright, were a part of the old Shakespeare and Company circle, but there were new voices here as well, such as James Baldwin and Anais Nin. Just as Shakespeare and Company had been a gathering space for the Lost Generation, as the World War I survivors were known, Le Mistral became a space where the Beat Generation congregated. “It was very comforting to have a point of reference where you could get books, and if you were starving, you knew you could get a place to sleep and a bowl of soup. It was really like a kind of maternal cow somehow. Even if you had enough money, there was always that place in the background where you could take refuge just in case. There were a lot of just-in-cases who did take refuge there,” the poet Allen Ginsberg said of the shop.

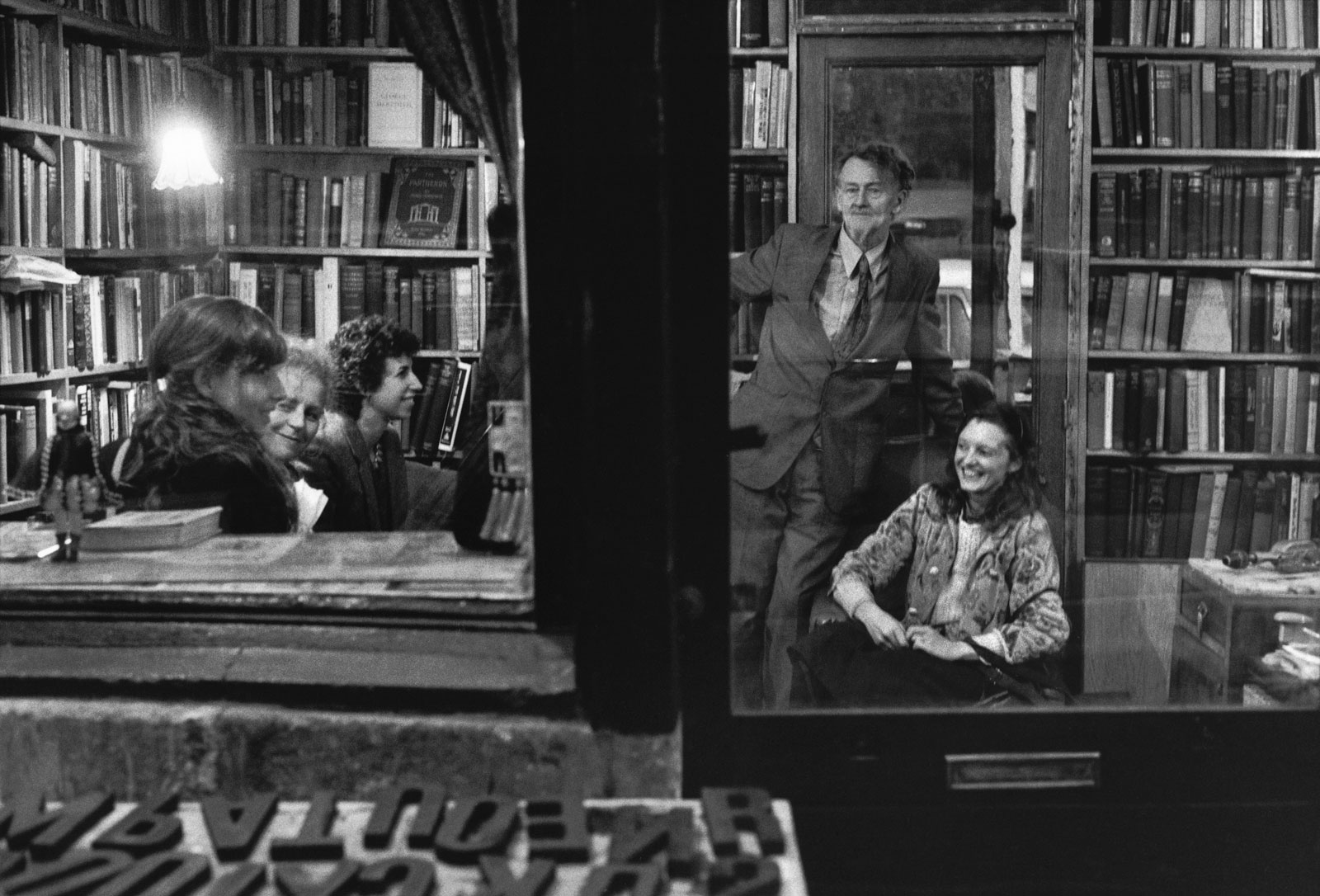

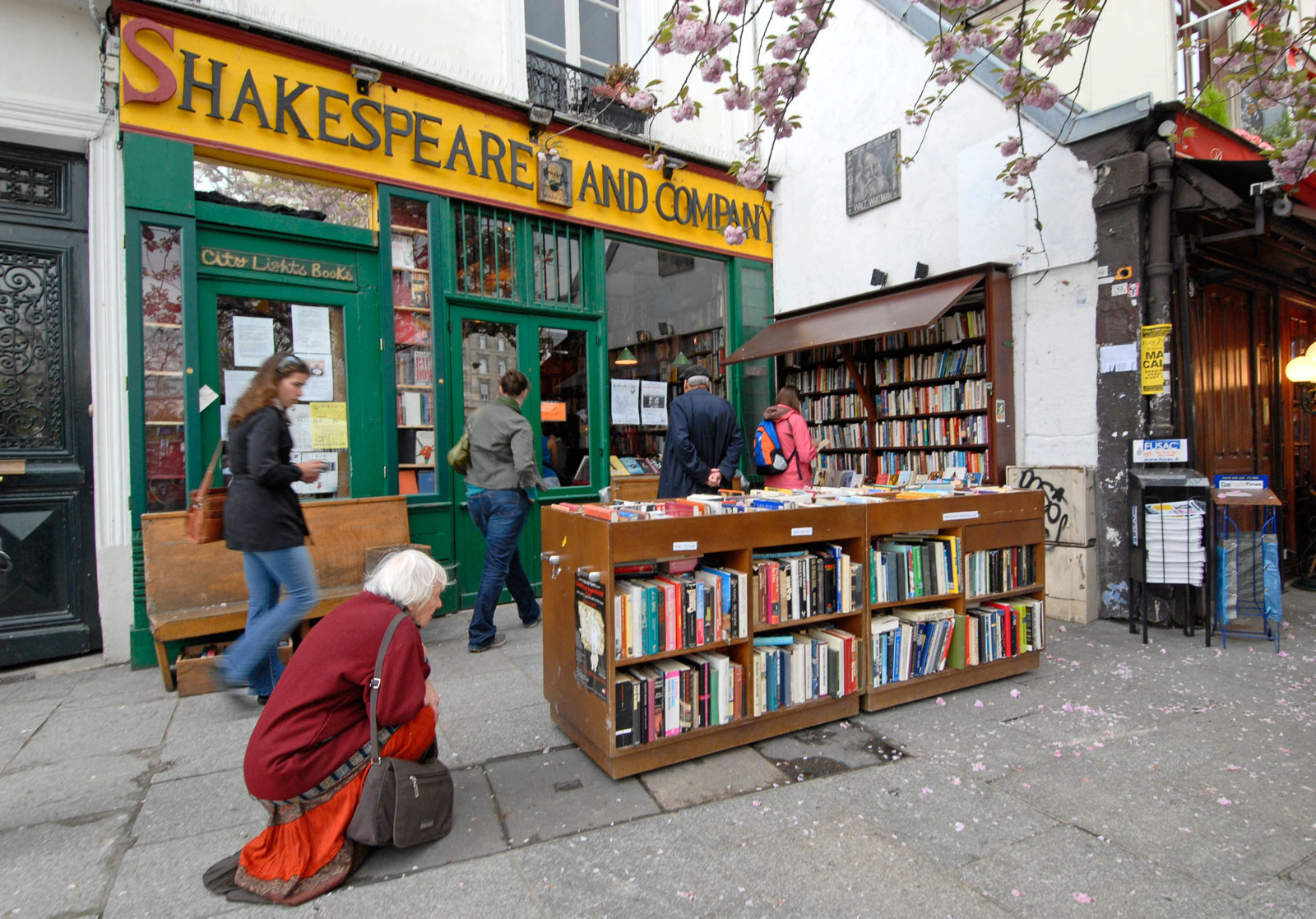

According to Whitman, it was Beach who recognized and designated Le Mistral as the spiritual successor to her Shakespeare and Company. After attending a reading at Le Mistral at George’s invitation, Sylvia became a regular customer. Eventually, she offered him the name “Shakespeare and Company.” Later, she made him a plaque that he displayed in the window: “Shakespeare and Company—Writer’s Guest House.” George eventually did take up Sylvia’s offer and Le Mistral was rechristened Shakespeare and Company on William Shakespeare’s 400th birthday in 1964.

Like Beach, Whitman had not only a love of literature, but also an idealistic vision for social change. To friends, Whitman was known for saying that his business was, in truth, “a little socialist utopia masquerading as a bookshop.” From the opening of his shop, George invited young writers to stay, to sleep and to live at Shakespeare and Company in exchange for a little help around the shop. These writers were dubbed “tumbleweeds” by Whitman, and since 1951, over 30,000 such tumbleweeds have called Shakespeare and Company home.

Whitman did not only name the shop in honor of Sylvia’s work. George Whitman’s daughter, Sylvia Whitman, now runs Shakespeare and Company and to this day welcomes tumbleweeds to live among the books. The shop, under Sylvia Whitman’s direction, has done much more than simply maintain her legacy of Beach and her father. Through the shop’s public programming, today’s most prominent authors discussing feminist issues have had a platform. In the last year alone, Shakespeare and Company has welcomed writers such as Lauren Elkin, Salena Godden, Caroline Criado-Perez, and Rachel Cusk to discuss their writing. Sylvia Whitman’s Shakespeare and Company is not just a monument to the past, but still a place where writers and readers gather and link their love of literature to the world around them.

In Shakespeare and Company today, there is a room dedicated to Sylvia Beach: make your way through the ground-floor labyrinth of floor-to-ceiling bookcases, ascend the creaky red staircase, where you’ll read a quote from Hafiz written on each step in white paint, “I wish I could show you when you are lonely or in darkness the astonishing light of your own being,” and you will find it. The Sylvia Beach Memorial Library is the space designated in the bookshop for reading. Here, readers can peruse the not-for-sale books, and read in one of the armchairs or cushioned benches, often with Aggie, the shop cat. In the prologue to the shop’s 2016 history book, Shakespeare and Company: A Rag and Bone Shop of the Heart, Jeanette Winterson celebrated the feeling of this space. “The bustle is the energetic kind of the life of the mind,” she noted. Above the entrance to the Sylvia Beach Memorial Library, George Whitman painted the following injunction: “Be not inhospitable to strangers, lest they be angels in disguise.”

Beach has long been celebrated for being “not inhospitable to strangers.” But “lest they be angels in disguise” speaks to the heart of her work: as a feminist and as a bookseller, she was devoted to the idea that there were unseen possibilities in those around her. Through her work, Shakespeare and Company became a place where that potential would be encouraged, regardless of a person’s gender, and despite the fact that the culture surrounding her insisted otherwise. So, as we celebrate one hundred years of Shakespeare and Company in Paris, we should celebrate not just her publication of Ulysses, but the way that Beach’s vision opened up new worlds of opportunity for women across Paris.

The description of Sylvia Beach’s arrest has been clarified.