For most of the twentieth century, the day-to-day lives of Asian Americans were barely depicted in mainstream art and media. While European immigrant groups like Italian Americans assimilated to become white—shaping their own representation along the way—and black Americans fought for civil rights and the control of their own narrative, Asian-American stories were left largely untold. Or perhaps they were simply unheard.

That could be part of why, nearly 200 years after the first Chinese workers arrived in California, we still occupy a confusing space in cultural consciousness, as a permanently foreign, largely apolitical monolith. Despite the valiant efforts of 1960s activists and academics (the same who invented the term “Asian American”), the work of Asian-American artists, and scattered pop breakthroughs (Joy Luck Club), Asian-American identity lacks narrative throughline in the twentieth-century story. The term’s too broad, the struggle too diffuse. Until recently, Asian Americans lacked cultural power; anything but the most exoticized tales were deemed confusing and irrelevant. Real and specific Asian-American stories were mostly excluded from film, TV, books, art, and photography. Without those crucial footholds, it could seem like Chinese Americans—for example—put our heads down sometime around the Oriental Exclusion Act and didn’t look up again until we were rich enough to oppose affirmative action. Those decades of silence pose the question: how had we been living?

As the daughter of a Chinese family that’s been in North America for at least four generations, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the era between first migration and now—that long, diasporic redaction. But I had never seen a really great photo of a family like mine until I saw the ones made by Michael Jang.

Jang is a San Francisco-based photographer who has just published his first monograph, Who Is Michael Jang? The volume, beautifully printed and clothbound by Atelier Éditions, accompanies an exhibition of Jang’s photographs at the McEvoy Foundation for the Arts in San Francisco, “Michael Jang’s California.” It’s a retrospective that is also a corrective: Jang has been making work for four decades, but most of these images have never been published before.

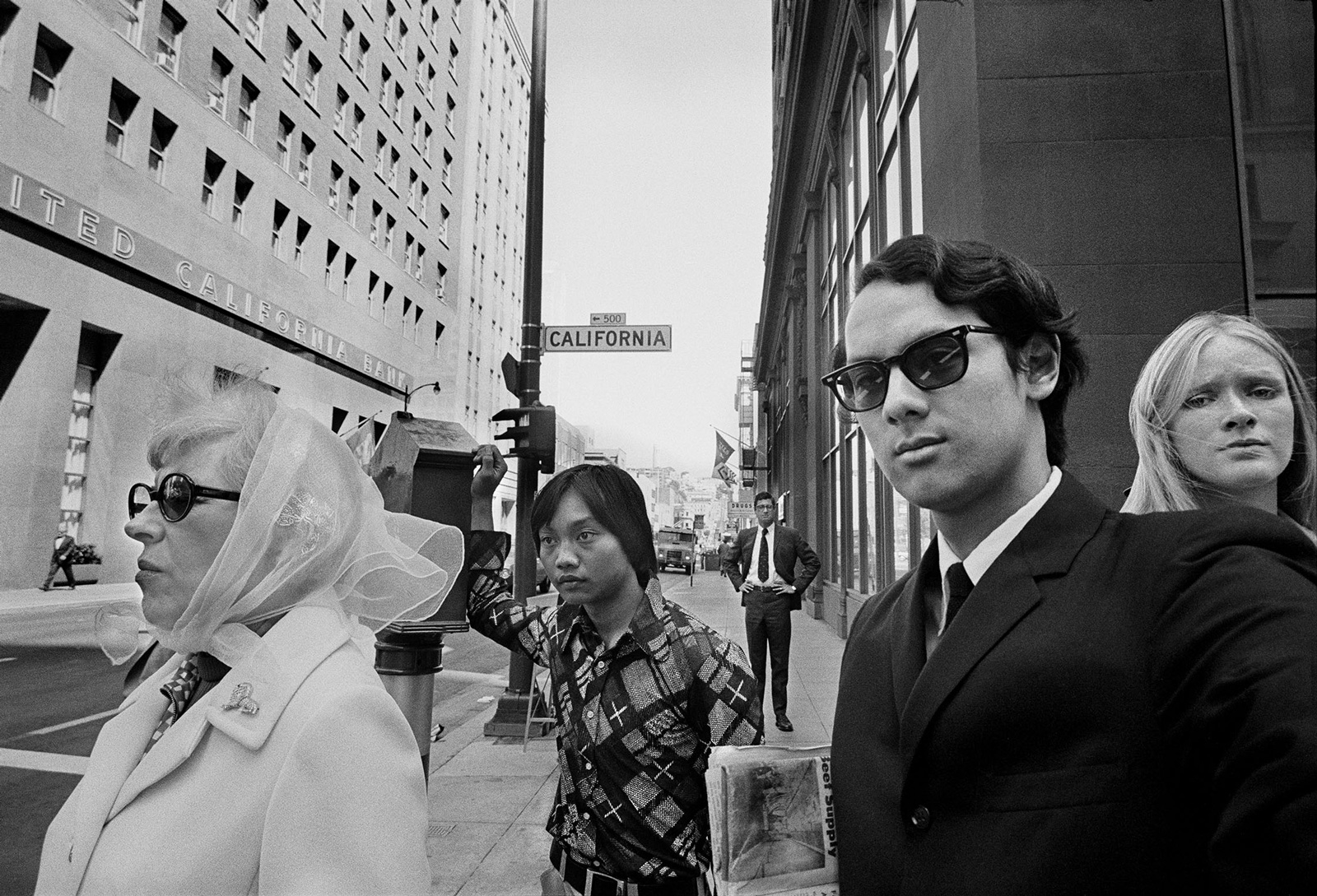

Jang, who is Chinese-American, studied photography at Cal Arts in the early 1970s, attending lectures by the likes of Lisette Model and Lee Friedlander. He turned toward commercial photography not long after graduate school, but the new exhibition and book mostly feature photographs taken before that turn. They cover a lot of ground, ranging from gonzo celebrity shots at the Beverly Hilton Hotel (to which Jang gained access with a fake press pass) to scenes of early San Francisco punk shows and the street, to intimate images of his relatives. The primarily black-and-white, 35 mm photographs are wry, bittersweet, and very California: there are Ronald Reagan and Frank Sinatra applauding themselves, Jerry Brown in a press scrum, the Golden Gate Bridge packed end to end with pedestrians. (The most recent pictures are from the early 2000s, when Jang started documenting his daughter and her friends in the San Francisco garage rock scene.) It’s a remarkable archive to have been kept out of sight for all those years.

So why haven’t we seen it before? The artist himself is partly to blame: in a recent interview for Aperture with Will Matsuda, Jang admits that when he took the pictures in the 1970s, he just didn’t think they were very good. He stashed them away in boxes, where they stayed until he decided to drop them off at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art for consideration in the early 2000s. To his surprise, the curators loved them. “Over the last ten years, I’ve brought them out in little pieces in zines or do-it-yourself pop-up exhibitions,” Jang said. “I’ve been testing the water in San Francisco, but it’s kind of like if your mom likes your pictures.” He may have the home team advantage, but this is too modest; Jang’s photos, with their bold flash and canny framing, would not be out of place alongside those made by Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, and Diane Arbus.

But the images of Jang’s that will stay with me are the ones that couldn’t have been taken by any of those photographers: they are the pictures of his own extended family.

Jang is third-generation American. His grandparents immigrated from China and both his parents were born in California. Michael grew up in Marysville, a former gold rush town north of Sacramento, and once, perhaps surprisingly, the home of a significant Chinatown, an embattled community established not long before the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. But the photos of Jang’s family in Who Is Michael Jang? were mostly taken in the Bay Area suburb of Pacifica, where Michael—then in his early twenties—was crashing with his Uncle Monroe, Aunt Lucy, and their two kids, Chris and Cynthia.

Advertisement

The photos of Monroe and Lucy Jang’s house show a living room where the furniture hangs low, couches and lounge chairs slouching toward the deep-pile carpet. There was a pass-through in the wall between the kitchen and the dining room to place dishes. Cynthia parted her long hair down the middle. Aunt Lucy—permed hair teased high above her plucked-thin eyebrows—watered flowers in the yard wearing matching geometric-patterned separates. The whole group unwound in the living room: parents reading, Cynthia on the phone, Chris (for some reason) lolling in an inner tube. Kids piled on the couch reading MAD and Archie. Uncle Monroe practiced his golf swing. It was the summer of 1973, and the daisies were in bloom.

“Old pictures often just look like old pictures,” Jang said in the Aperture interview. “So what is it that makes these photos interesting still? The vintage rugs? I honestly don’t know.”

To me, the dated interiors read like evidence—evidence that another family like mine lived in a house like this.

Because although my family landed on the west coast of Canada instead of California, we have a lot in common with the Jangs. My mom and her siblings—like Jang—grew up in a small, semi-rural town that had once had a significant Chinatown. The photos of their childhood shaped my understanding of where we came from: their teen years were all bell bottoms, wood paneling, aluminum Christmas tree. My mom in a turtleneck, her straight black hair Baez-long. Her gangly brothers in ringer tees, her sister in wireframe glasses. My grandma, who had grown up in rural China and moved to Canada as a teenager, wore a perm for her entire life, went to square dances at the Anglican church, made Jell-O. My grandfather, like Jang’s dad, was born in North America, and as the Canadian-born father of Canadian-born teenagers, he slicked back his hair with pomade, barbecued, and drove a huge American car.

My grandparents aspired to—and in many ways did—live a completely normal small-town Canadian life, with kids who played sports and might get to go to college. But what that meant to them was not the same as what it meant to many of the white families around them. My grandfather, despite being born in that same town, didn’t learn English until he was seven. Alienated from his family’s white neighbors, he grew up being chased and tormented by the white kids around him. My grandmother, after marrying my grandpa and moving there to be with him, became one of the only Asian women around, intimidated by white men; my mother remembers my grandmother receiving lewd phone calls, being afraid to answer the door when they were home alone. As a kid, my mother scrubbed and scrubbed at her own skin in the bath, wishing there was a way to turn it white. She’s easy to find in the group photo taken at her prom: smiling radiantly, she’s the only dark face in a vast pale crowd.

My family’s experience is a common one, from Honolulu to Vancouver. But I’ve rarely seen this type of deep Asian Americana (or Canadiana) reflected back. Japanese Americans have a specific word for my kind of temporal relationship to the motherland: yonsei—four generations since immigration from Japan. There’s no Chinese diasporic equivalent, no succinct term to signify the century-plus we’ve spent on this continent. People like us can be hard to locate on the North-American axes of race and class. We may even struggle with that ourselves. (We have both found ourselves pitted against other people of color, and weaponized race to justify our own prejudice.) Seeing the Jangs, the mundane details of their lives, in an exhibition and art book feels, to me, like more than representation. It feels like putting a name to an entire experience. It feels like public confirmation.

Michael Jang’s photography is being published and exhibited at a time when artists and curators are actively working to reinsert the stories of people of color into photographic history, an apparently simple goal that once seemed inconceivable. This endeavor includes more grassroots efforts—Instagram archives such as Renata Cherlise’s Blvck Vrchives, which collects visual narratives of the African diaspora, Guadalupe Rosales’s Latinx-focused Veteranas and Rucas, and Doris Ho-Kane’s 17.21 Women, documenting Asians and Pacific Islanders—as well as shows at larger institutions and commercial galleries alike. Jang’s “rediscovery” has a lot to do with his talent, but it also has to do with a more hospitable cultural moment. As Jang asked one interviewer recently, “How many Chinese kids in the Seventies went to six years at an art institute and now has something to show for it?”

Advertisement

In her mostly astute catalog essay for Jang’s book, SFMOMA curator emeritus Sandra S. Phillips writes, “What strikes the observer of Jang’s prolific family albums, both the ones created by his father and the records he has kept of his own life, is how entirely middle class, or ‘middle American’ the family culture was, how there is not a trace of ethnic sentiment at all. They were completely Americanized.” Phillips has been a champion of Jang’s work, and this could be taken as a compliment—or a neutral observation. To me, it sounds more as though she doesn’t know how to read a family like the Jangs.

And she is not the only one: a glowing review of Jang’s work in Mother Jones calls the family series a snapshot of “all-American suburban existence” and “a fascinating, intimate look at life in the Bay Area suburbs in the 1970s.” The writer is so careful not to engage with Jang’s Chinese Americanness—he doesn’t mention race once—that he misses one of the most poignant things about the photos: in California, Chinese-American families had only really started moving to these kinds of suburbs about a decade earlier, because no one would agree to sell them property before that time. When Jang was making these photos, Uncle Monroe and Aunt Lucy were raising Asian kids in a town that was 94 percent white.

When I look at the pictures that Michael Jang made, I don’t see a family with “not a trace of ethnic sentiment”; I see a Chinese-American family that was among the first who could even dream of this kind of middle-class comfort. Looking at the images, I immediately noticed the promotional calendar from a local Chinese grocery on the wall, the rice cooker, the aquarium with koi. In one photo, Aunt Lucy is shown talking on the phone: she wears a 1970s caftan dress and sits below a painted portrait of herself, in which she’s wearing a traditional Chinese jacket. These elements aren’t at odds with one another. By making these photographs of his relatives, Jang was doing exactly the same thing that Robert Frank, Eggleston, and Winogrand did. He was capturing the particularities of modern life.

Phillips describes this family as “Americanized,” as if the act of being born with an Asian face calls for later assimilation. And no doubt the Jangs felt the pressure to conform, to prove they made sense in the very place that they were from. Pop cultural records of the twentieth century may not include very many families like them. But the Jangs never had to learn how to live like Americans. Just by being here, they were doing it already.

“Michael Jang’s California” is on view at the McEvoy Foundation for the Arts in San Francisco through January 18, 2020. Who Is Michael Jang? is published by Atelier Éditions.