“If you don’t drink champagne, go away!” read a neon sign above the entrance to Bal Tic Tac, which opened its doors in Rome in 1921. The nightclub was designed by the artist Giacomo Balla, a leading proponent of Futurism and co-author of the movement’s 1915 manifesto, Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe. Futurists believed that the frantic speed of the machine age should be echoed in the design and decoration of one’s environment. Accordingly, every aspect of the club’s interior, from the floor to ceiling paintings of brightly colored intersecting shapes to the orchestra balcony, and even the light fixtures, was an attempt to capture the swirling, kinetic movements of the dance floor.

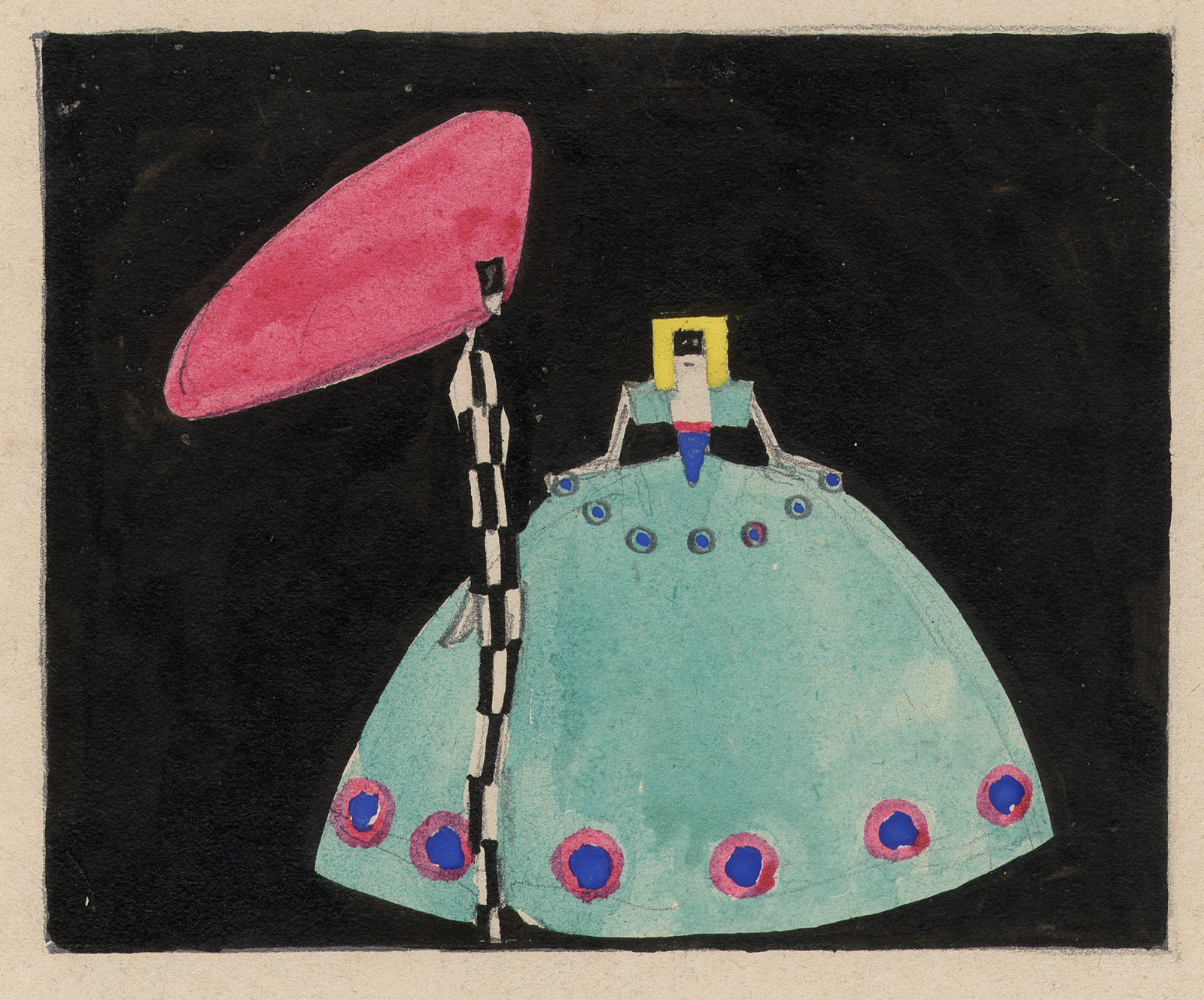

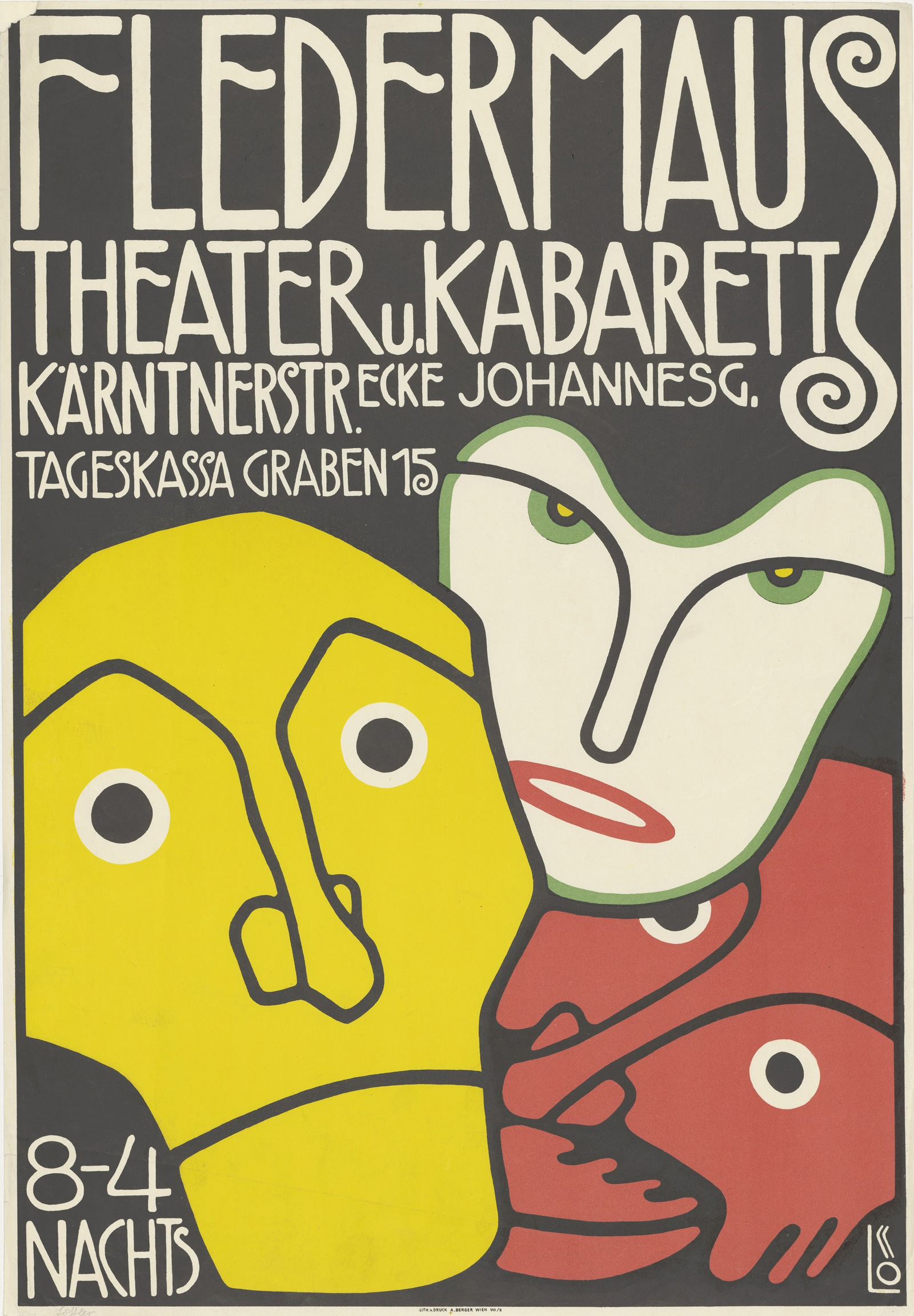

Alcohol served in a theatrical setting had been one of the allures of Cabaret Fledermaus, a decade earlier, in Vienna. With a “fancy drinks” menu that included the “Pick Me Up,” “Kiss Me Quick,” and “Cabaret Smash,” the Fledermaus bar was a ceramic-tiled masterpiece, its black-and-white checkerboard floor a striking contrast with the fantastical motifs, in a riot of primary colors, that adorned the walls. Designed by Josef Hoffmann, it’s still remembered today as one of the most iconic pieces made by the Wiener Werkstätte, Vienna’s famous cooperative artistic workshop.

Its life-size recreation—by teachers, students, and archivists at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna—is undoubtedly the pièce de résistance of “Into the Night: Cabarets and Clubs in Modern Art.” All the same, the thrust of this rather ingenious new exhibition at the Barbican Centre in London is that each of the clubs and cabarets included was much more than just an elaborately decorated drinking den. The show isn’t simply interested in cabarets and clubs in Modern art, or Modern art in cabarets and clubs, for that matter; this is a deeper and more thoughtful examination of the symbiosis between the two.

Organized by city, it’s a compendium of some of the world’s most famed nightspots, from the 1800s through the 1960s. Each section offers up a rich selection of decorative objets d’art and ephemera belonging to the spotlit venues; furniture, silverware, programs of entertainment, the art displayed therein, video footage (where available) of performances hosted by the cabarets and clubs. Also included is a broader collection of artworks, either created by artists closely associated with the establishments (though not necessarily part of the décor of the club in question, nor displayed there), which helps to capture the spirit of the cities’ nightlives. Four extra rooms are also given over to “recreations”: of the aforementioned Fledermaus bar; of Paris’s Chat Noir shadow theatre; the Mbari clubs in the Nigerian cities of Ibadan and Osogbo; and Theo Van Doesburg’s Ciné-Dancing, the centrepiece of Strasbourg’s L’Aubette, a grand hall that combined dancehall, cinema, and restaurant.

Each of the clubs included in the show attracted the most avant-garde artists, writers, musicians, dancers, poets, and intellectuals of their eras, both as punters and performers. These venues were just as significant as the gathering places where artistic movements were cultivated as they were performance and gallery spaces. We should think of them, the curators suggest, as “total sensory experiences.”

This is nowhere more apparent than in Rome’s Cabaret del Diavolo (Devil’s Cabaret), an impressive opera d’arte totale in the vein of the German aesthetic notion of Gesamtkunstwerk, which opened in 1922 only a few streets away from Bal Tic Tac. “Tutti all’inferno!!!” invited the club’s calling card: Everyone to Hell!!! Its owner, the writer Gino Gori, commissioned Fortunato Depero—Balla’s co-author on Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe—to create an interior inspired by Dante’s The Divine Comedy. His flyer for the opening night’s entertainment promised a program of live performances by Futurist artists that would rival today’s most intensely immersive theatrical experiences. These included a “demonic speech” performed by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in the “Inferno” room (the venue’s multilevel spaces were all themed around one of Dante’s three realms of the dead); the poet and dramatist Luciano Folgore reciting his parodic work in “Purgatorio”; and the composer Alfredo Casella and his two bellezza (“beauties”) performing celestial music in “Paradiso.”

A decade earlier, another club with a manifesto, the Cave of the Golden Calf in London, offered its guests surroundings “which after the reality of daily life, reveal the reality of the unreal.” Although not as all-encompassing an experience as the Cabaret del Diavolo, the murals, paintings, and carvings—the works of artists Spencer Gore, Wyndham Lewis, Jacob Epstein, and Charles Ginner—that decorated the Mayfair club’s interior were all designed in keeping with the cabaret’s pagan-inspired theme. None other than the typographer and sculptor Eric Gill—today notorious for his disturbing sexual proclivities—designed the club’s motif: a golden calf in a state of tumescence. Despite proving extremely popular with London’s arty night owls, the Cave of the Golden Calf struggled financially. It closed its doors after only two years, in 1914, on the eve of World War I, and its founder, the Austrian impresario Frida Strindberg (formerly married to the Swedish playwright August Strindberg), fled to the relative safety of America, leaving a host of unpaid bills in her wake.

Advertisement

A fair share of the venues included in the exhibition found their fortunes, good and ill, tied to the geopolitical tumult of their times. As the death toll rose on the battlefields of Flanders, neutral Switzerland offered something of a refuge for exiled artists and intellectuals, and they flocked to the short-lived Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. Though open for only five crazy months, from February to July 1916—the energy that created it having fizzled out as quickly as it sparked into being—it achieved lasting fame as the birthplace of the Dada movement. “While the thunder of the batteries rumbled in the distance,” recalled Jean (Hans) Arp, “we pasted, we recited, we versified, we sang with all our souls. We searched for an elementary art that would, we thought, save mankind from the furious folly of these times.”

In the early 1920s, a venue on the other side of the globe, Mexico City’s Café de Nadie (Nobody’s Café), similarly became a gathering place for writers and artists—in this case, an avant-garde connected to Estridentismo (Stridentism), the movement founded by the poet Manuel Maples Arce in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution. A wall of densely packed woodcuts in the Mexico City room of “Into the Night” offers a taste of the works on show in the subsequent Carpa Amaro, an itinerant cabaret that also provided an exhibition space for the members of ¡30-30!, the more politically minded offshoot of the Estridentismo group, whose mission was focused on bringing art to the masses.

Similarly, Nigeria’s Mbari Clubs—“Mbari” is an Igbo word that means “creation”—of the early 1960s emerged after the country’s independence from colonial rule, so it made sense that the intellectual communities that grew up around these venues would be a meeting point between indigenous tradition and mythology and Western modernism. Mbari Mbayo, for example, which opened in Osogbo in 1962, became the home of the club’s founder Duro Ladipo’s visionary Yoruba opera company. A year earlier, the Mbari Writers and Artists Club had opened in the university city of Ibadan, founded by leading cultural figures such as the poets Christopher Okigbo and John Pepper Clark, the artists Uche Okeke and Demas Nwoko, and the writers Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka. It was an outdoors performance space, art gallery, library, and office all rolled into one, to which anyone was welcome. Thus, by their very nature, the Mbari clubs lacked the formal, meticulous décor of their European-based counterparts, which means the works included here are limited to those produced by the writers and artists associated with the venues.

Pickier about its clientele, Rasht 29, another exemplar of postcolonial-Modern milieu-making, was a members-only club that offered Tehran’s artists somewhere to discuss contemporary culture, screen avant-garde films, and stage poetry readings and experimental theatre. Established by the architect Kamran Diba, the artist Parviz Tanavoli, and the musician Roxana Saba, it ran from 1966 to 1969. An eye-catching flyer promised a venue “where atmosphere is arty.” It reads like a missive from a now lost world, one of freedoms and permissiveness that was swept away in the Islamic Revolution of the following decade.

One time and place that has achieved a certain immortality for its transgressive, flamboyant nightlife is Weimar Berlin. Thanks to film and television hits like Cabaret and Berlin Babylon, the works on display here are probably the best known in the exhibition (bar only, perhaps, those of Paris’s Chat Noir). Weimar Germany’s relaxed censorship laws allowed what we would now identify as queer culture to thrive, and the city’s nightspots were full of cross-dressers and same-sex couples. In her element, too, was the “New Woman,” with her masculine-style clothes and bobbed hair, seen here in the exhibition in the form of Jeanne Mammen’s portraits of female revelers, which, with their sympathetic portrayal of queer desire, are positively tender compared to the contemporaneous caustic caricatures offered by artists Max Beckmann and George Grosz.

Advertisement

Also on show is Otto Dix’s intimate pastel portrait, drawn in 1925 of the then twenty-six-year-old cabaret dancer Anita Berber, one of the most provocative performers of the era, notorious for her dance “Cocaine,” in which she wore a leather corset that exposed her breasts to play a drug-addicted sex worker. Berber died only three years later, in 1928, having destroyed herself with drink and drugs, the shadows of which are already apparent on her face in Dix’s drawing. Perhaps unsurprisingly, a moral panic about this culture of decadence and debauchery eventually galvanized the government, which plastered the warning “Berlin, stop and think, you are dancing with Death” across the city’s advertising kiosks.

For those who pooh-poohed such alarmism, Curt Moreck’s 1931 Führer durch das ‘lasterhafte’ Berlin (Guide to ‘Depraved’ Berlin) would have proved invaluable. With its striking cover, depicting an all-but naked woman raising a coupe of Champagne, the pages inside list the city’s bars, pubs, and dance halls, accompanied by illustrations by familiar artists, including Paul Kamm’s illustration of a well-known lesbian bar, Café Olala. An entertaining companion piece to Moreck’s Baedeker parody is E. Simms Campbell’s A Night Club Map of Harlem (1934). One of the most delightful pieces included in the show, it’s a diligently illustrated and captioned bespoke guide to the top Harlem hotspots, including Tillies on 133th Street, which offered sustenance for hungry bar-hoppers in the form of some “really good” fried chicken, Gladys’ Clam House, home of the Blues singer Gladys Bentley, an openly lesbian performer who wore “a tuxedo and highhat,” and Club Hot-Cha, where those in the know “ask for Clarence,” but not earlier than 2 AM, before which, the map warns, “nothing happens.” As the map clearly shows—with fur-clad white women and top-hatted white gents driven uptown by their chauffeurs for their nightly amusements—the popularity of the Harlem scene challenged social boundaries. These clubs and cabarets weren’t simply at the artistic vanguard; they broke the unofficial color bar too.

Yet it is in bringing our attention to what made these clubs so ground-breaking at the time—their existence as white-hot centers of the artistic avant-garde, of gathering places for revolutionary politics, and spaces in which societal conventions could be bent or broken—that the exhibition reveals its limitations. Precisely what makes each and every one of the venues featured worthy of inclusion is that they were more than just works of art, more than their often famous guest lists, more—put simply—than the sum of their parts, i.e. the works on display here. The impressive recreation of the Fledermaus bar points to one element of these demi-monde that the show is missing—a roomful of carousers, raucous chatter, music, and performers. It is arty but lacks atmosphere.

Clearly aware of this, the curators have made some effort to bring the gallery to life: three evenings a week, it stays open late, and you can purchase a cocktail (though not one of their original offerings, I’m afraid) at the Fledermaus bar, to sip while enjoying the live music performance in the room that’s supposed to be a recreation of L’Aubette’s Ciné-Dancing. (The original venue was designed in the late 1920s by the Arps and van Doesburg, the Dutch artist who was the founder and leader of the De Stijl movement and also contained a tea-room, a cabaret, billiards room, bars, and restaurants.) Although it was clearly a welcome addition for the politely attentive audience on the evening I visited the gallery, it was a far cry from the buzz of an actual nightclub.

In general, the show’s recreations felt paltry compared to the originals. To call the room displaying copies of a selection of puppets used in the Chat Noir’s famous shadow theater a recreation of the Parisian establishment’s legendary draw seems over-ambitious. The original, we’re informed, was installed in a grand room hung with drawings by Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. By far the most disappointing, though, is that of Mbari clubs: a corrugated iron roof, some carved wooden latticework, and a few low wooden stools sat in front of video footage of the original provides little in the way of ambiance.

Such lackluster gimmickiness tarnishes what’s otherwise an eye-opening, well curated exhibition that plays to the Barbican’s own strengths as a cultural venue with a gallery, concert and performance halls, cinemas, bars, restaurants, and a library. That what was once the purview of the avant-garde has thus been institutionalized in the Barbican’s signature 1960s Brutalist spaces left me wondering, a little disconsolately: Where are these venues today?

“Into the Night: Cabarets & Clubs in Modern Art” is at London’s Barbican Centre through January 19, 2020.