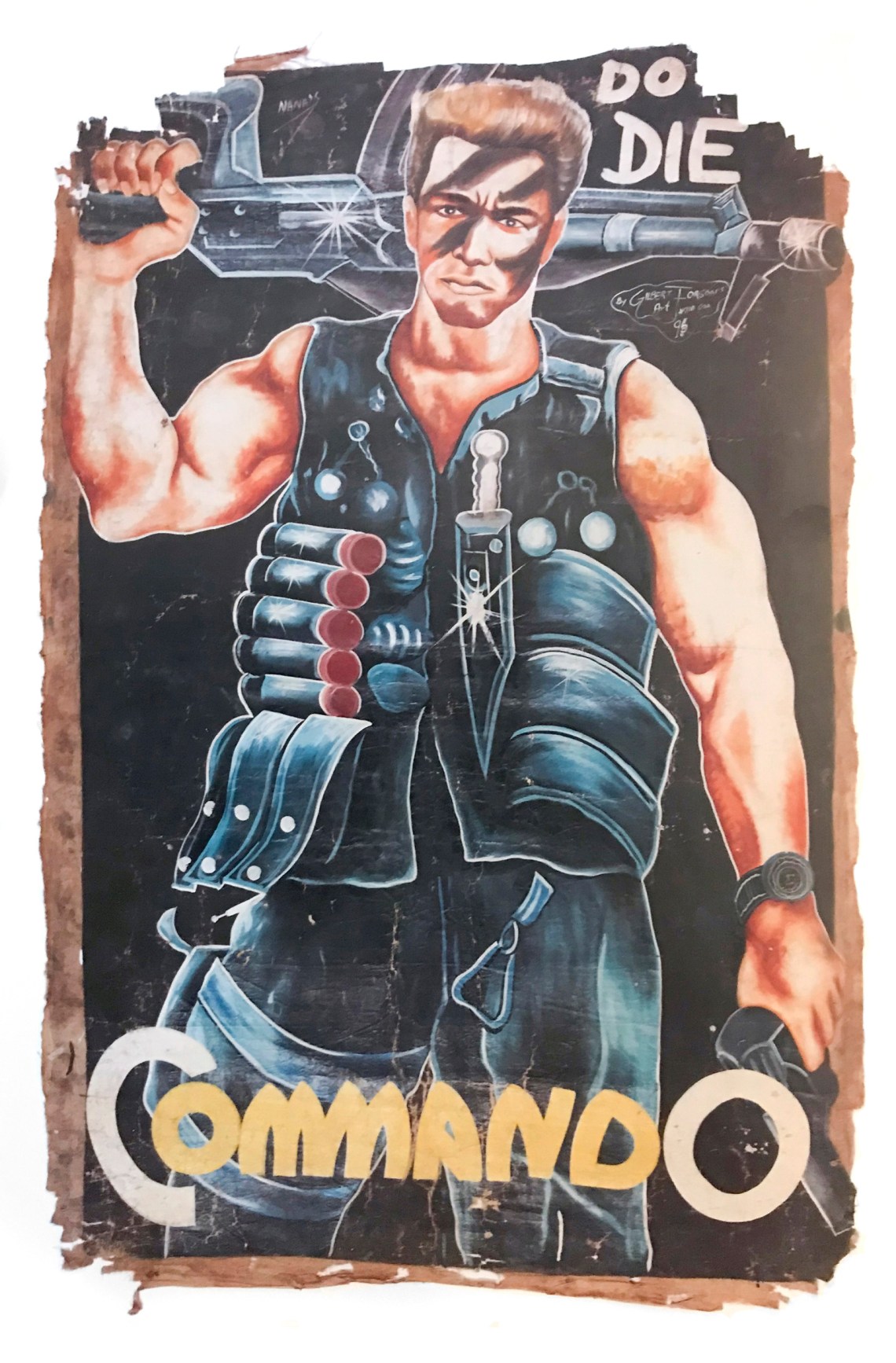

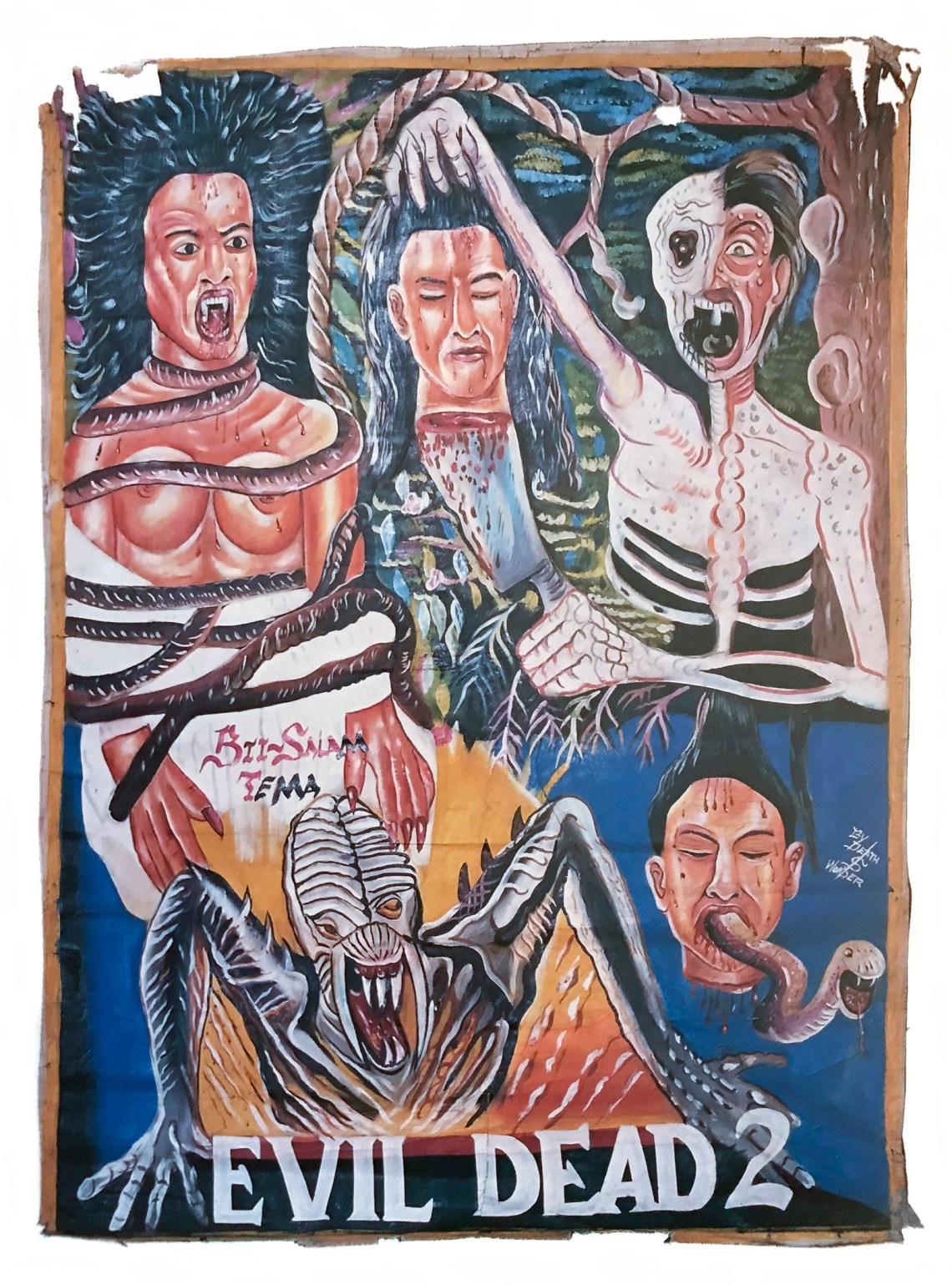

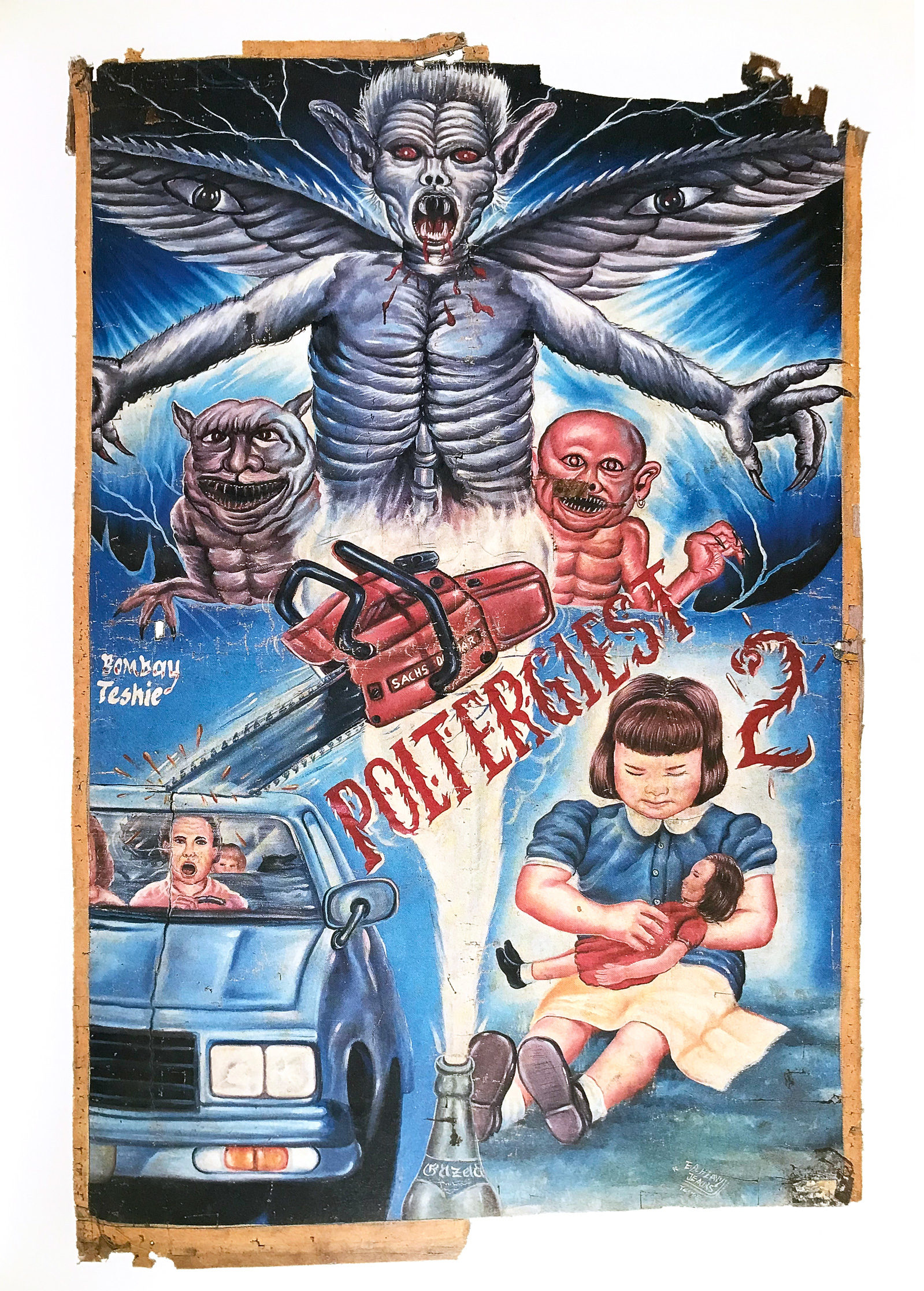

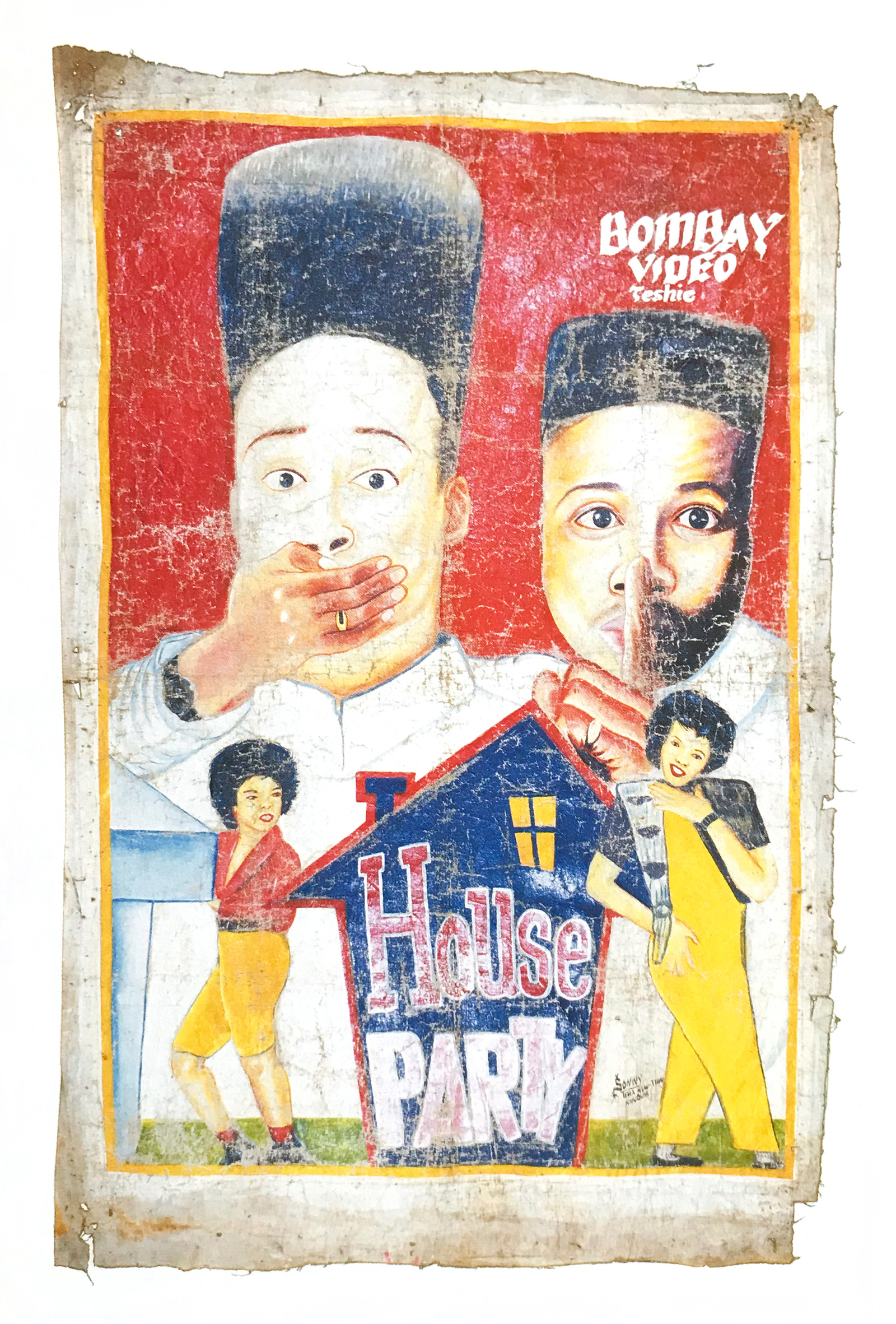

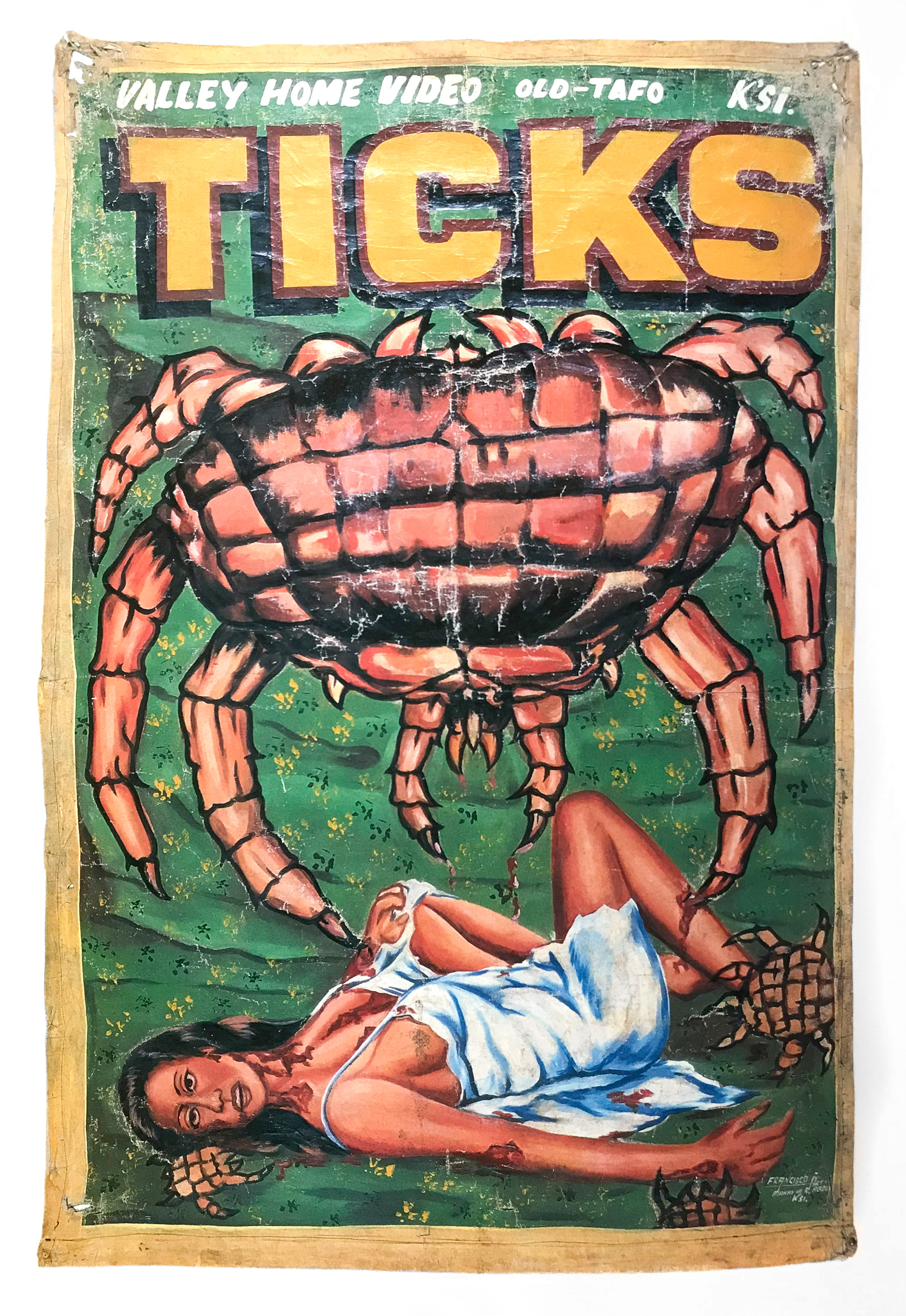

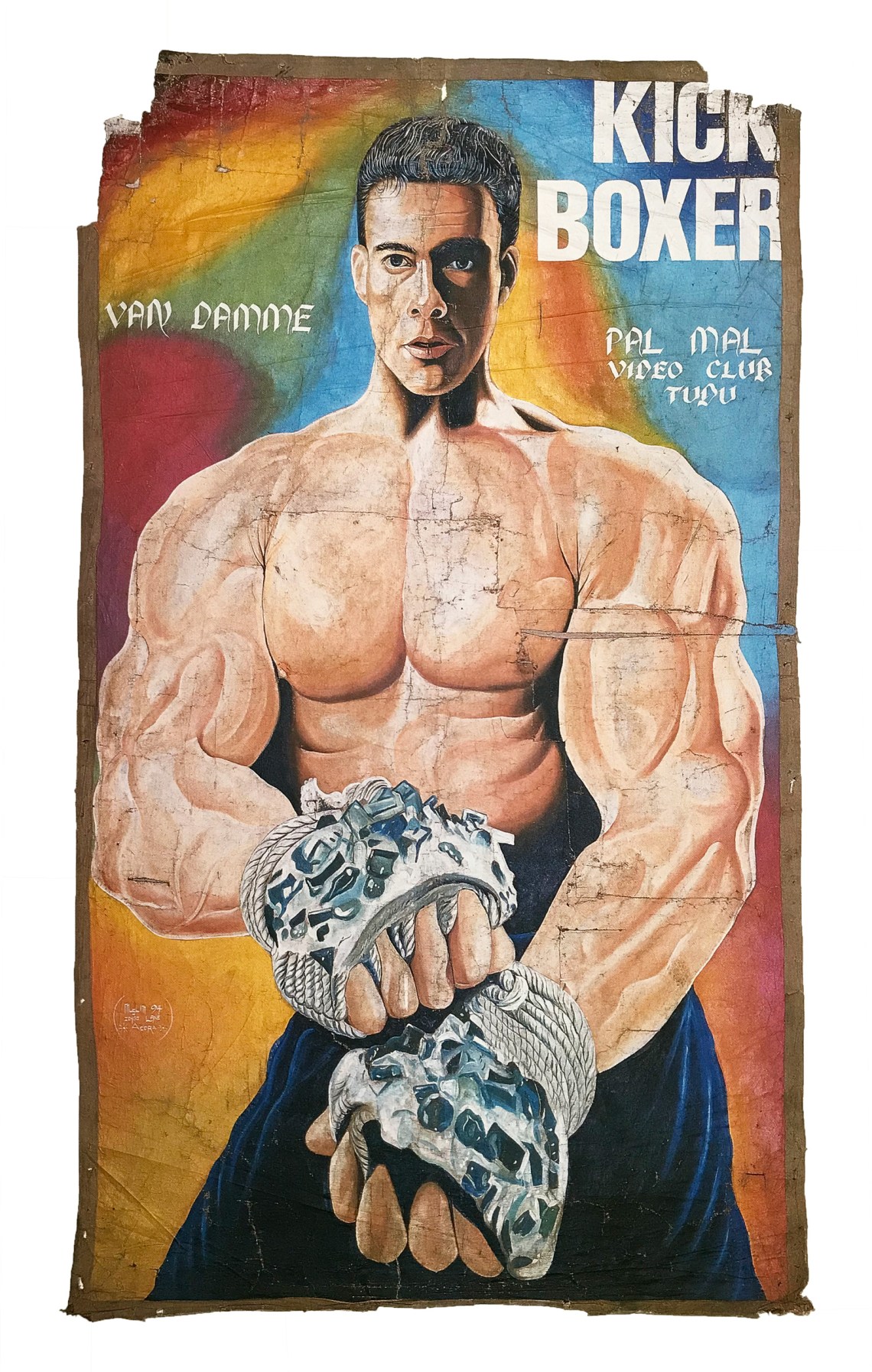

When you walk into “Baptized by Beefcake: The Golden Age of Hand-Painted Movie Posters from Ghana,” an exhibition now at New York City’s Poster House, you are confronted by the stares of film heroes of the late Eighties and early Nineties—each with a distinctly Ghanaian rendering. For over a decade beginning in the 1980s, paintings like these—typically made using acrylic paints on recycled flour sacks—were an answer to the country’s lack of large-scale commercial color printing, as the show’s curator, Angelina Lippert, explained to me. Local interpretations of the original Hollywood VHS sleeves, or representations of scenes from the movies embedded with local symbolism, ushered in this genre of “Africanized” Hollywood aesthetics. Across a continent reeling from revolutions and counterrevolutions, characters like Rambo, Conan, and Commando particularly resonated with viewers inspired by their exaggerated strength and daring confrontation with the powers that be.

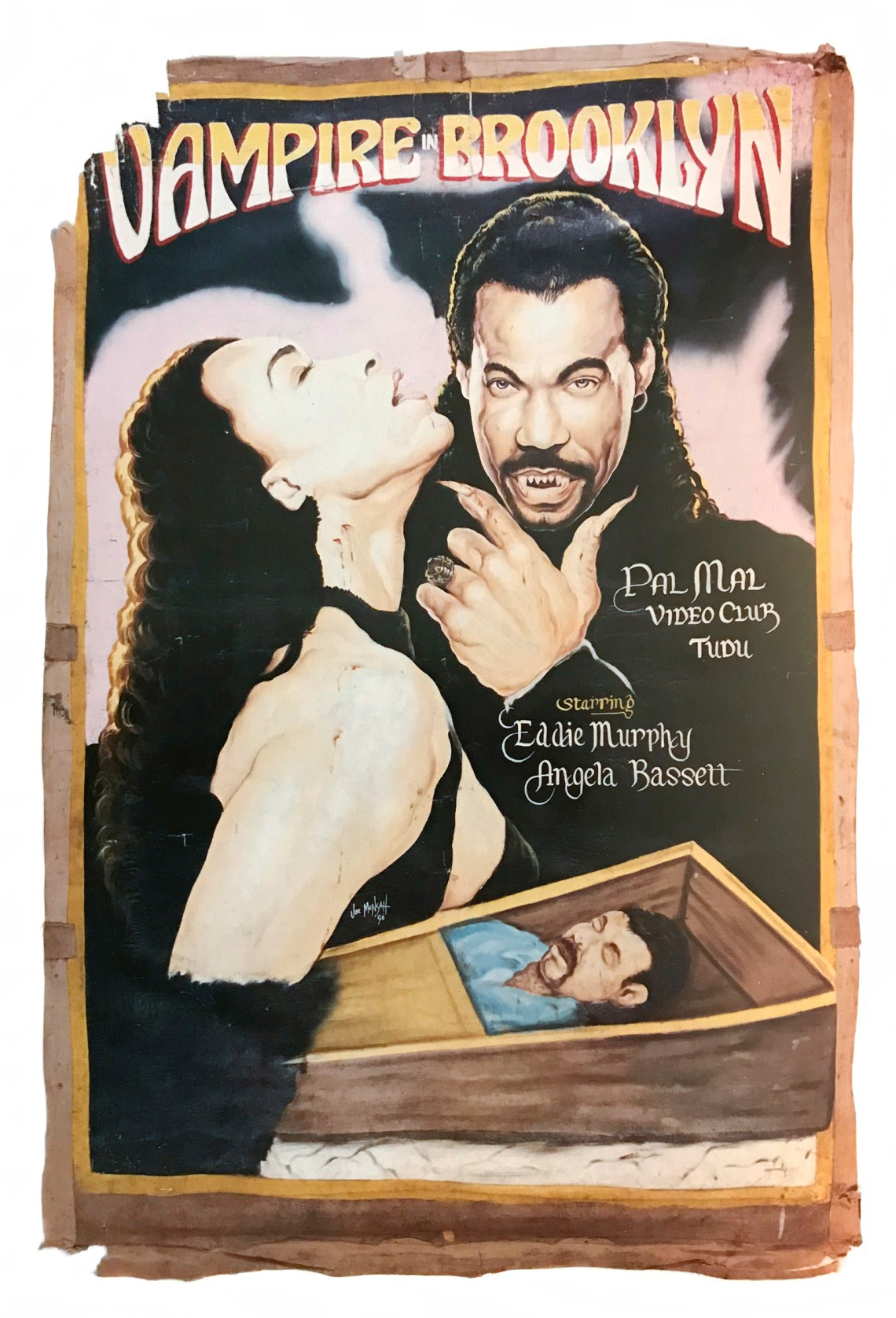

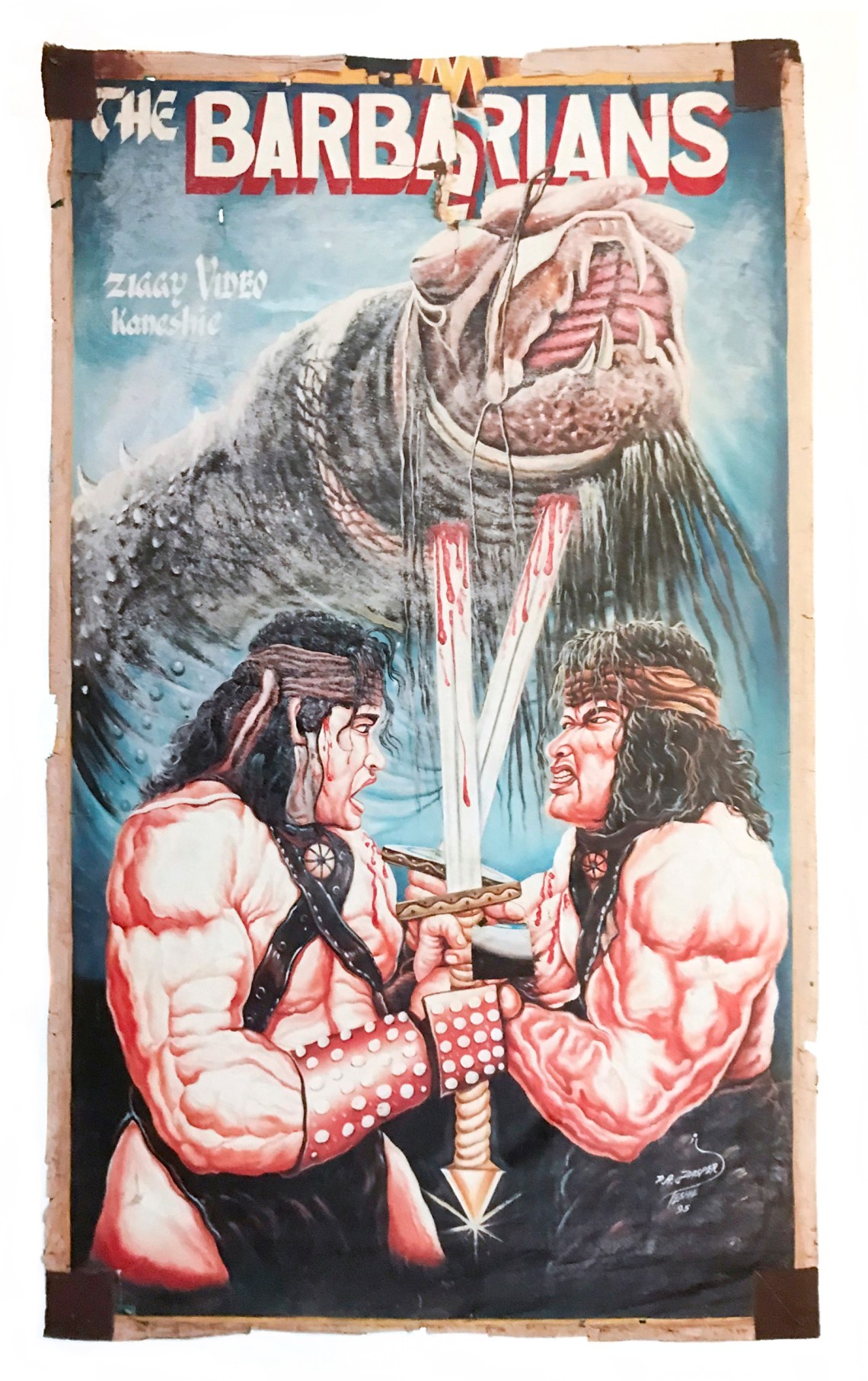

Sandwiched between the poster for Aliens (1990) and Ghost (1990), and across from Eddie Murphy’s Vampire in Brooklyn (1996), is perhaps the poster most representative of the genre: Daniel Anum Jasper’s seventy-four by forty-six-inch painting of The Barbarians (1995). Two muscle-bound men—the titular barbarians of the movie—their long dark hair cascading down their naked upper bodies, thrust their swords upwards, piercing the neck of a giant snake that looms above them. These crossed swords, according to the exhibition panel, refer to the “Akofena” symbol, which represents courage and valor in many West African motifs—somewhat ironic, given that they win the day in spite of their childish antics.

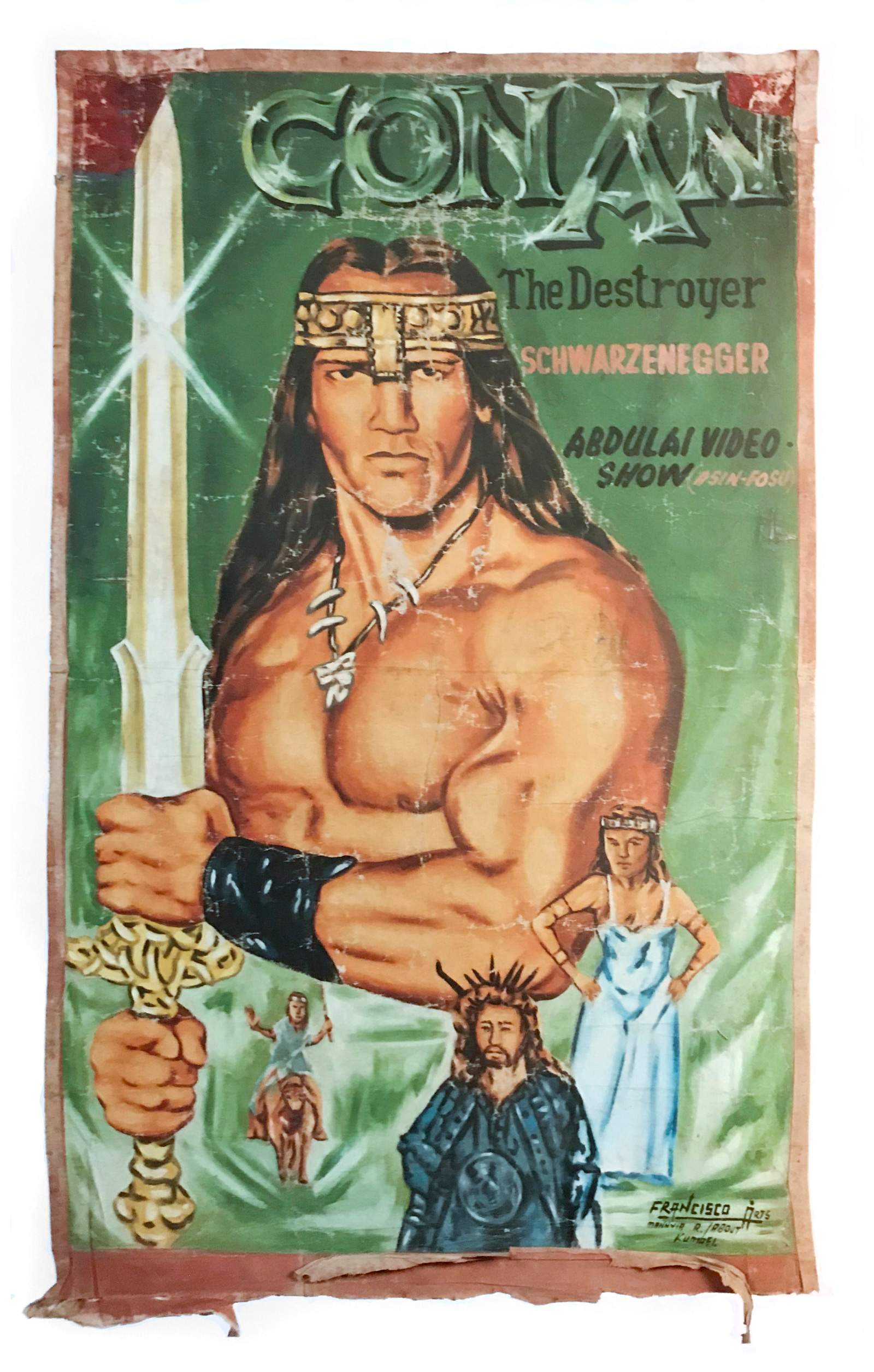

As a late preteen in Tema, a coastal city twenty miles from Accra, Ghana’s capital, I underwent a short-lived apprenticeship with our church’s piano player, compelled by my parents’ dreams of upward mobility (a Bach-playing son wouldn’t hurt). The pianist also managed the local video rental store. The most positive outcome of this association for me was that in exchange for a shift spent rewinding returned VHS cassettes with a manual crank, I could rent a movie or two for free. The Schwarzenegger films Conan the Barbarian (1982), Conan the Destroyer (1984), as well as The Barbarians, which one blogger summarized as a “sword-and-sorcery version of Dumb and Dumber,” came home with me this way.

At school with the other boys, we would pit heroes from different movies against each other and arguments would ensue—for instance, about whether the Barbarians could defeat Conan in a fight. Seeing the poster took me back to evenings spent watching movies with relatives visiting from outside the city, and I remember feeling a deep sense of sadness seeing the twins spend crucial years alienated from their people and culture. The Barbarians follows the orphaned twins, who have been kidnapped from their nomadic tribe of circus-like entertainers, as their captors separate them and each is made to believe the other dead while training for a gladiator-like combat where they will be forced to fight each other to the death. Unsurprisingly, they recognize each other during the fight and make a break for the woods to find their way home. Their sibling squabbles take up most of the rest of the film—they appear eager to make up for lost time—until they defeat the evil king who kidnapped them and slay a dragon to recover the tribe’s magical ruby.

You wouldn’t know about the dragon looking at the original American movie poster: a subdued, dark palette shows the brothers, clutching their swords in a misty forest, one standing and the other crouched, watching warily for danger ahead. Inclusion of the dragon might have been considered a spoiler in the original artwork. But it’s depiction as a large snake in the Ghanaian version can be attributed to the fact that the serpent has historically appeared in local stories as an evil beast to be vanquished, and thus would have served as a recognizable draw for the local audience.

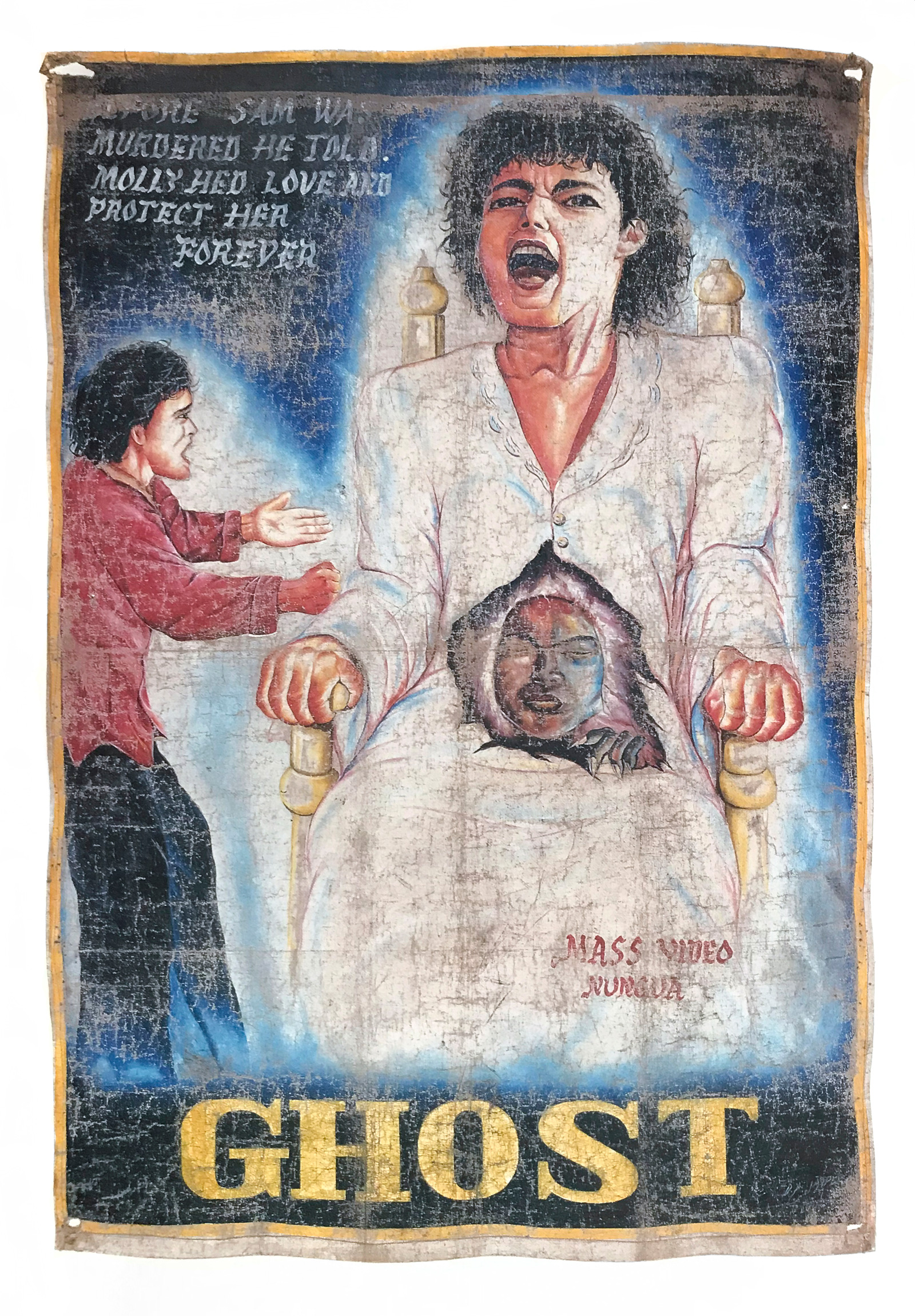

The poster for Ghost, 1990’s top grossing movie, a romance starring Patrick Swayze and Demi Moore, is a great example of artistic improvisation while foregrounding local tastes and mores. In Jasper’s rendition, the canvas is largely taken up by a woman dressed in all white (Moore), sitting on a white chair with what appears to be a human face protruding from her stomach—an imaginative and completely inexplicable flair. Swayze, a ghost for much of the movie, appears on the canvas as well, gesturing imploringly toward Moore. The original, with Swayze kissing Moore’s neck, both of them naked, would have been too licentious to reproduce.

The spirit of innovation, spontaneity, and creativity conveyed by the posters of this era reflected the cultural and political climate of the time, as 1993 marked the end of almost three decades of military dictatorships. When Kwame Nkrumah gained independence for Ghana from the British in 1957, he took over all the commercial theaters, and transformed the colonial Gold Coast Film Unit into what would become the Ghana Film Industry Corporation. The organization’s mandate was to educate Ghanaians with films about local development projects and the independence struggles in other African countries in order to build a cohesive sense of “African identity.” After the 1966 coup that toppled the first post-independence government, subsequent administrations neglected the GFIC, leading to the slow death of the Ghanaian film industry.

Advertisement

It was the advent of VHS technology in the late 1980s that kickstarted a revival of the local Ghanaian film industry, as the scholar Birgit Meyer has observed. In 1985, the self-taught artist Alex Nkrumah Boateng began painting posters for mobile cinema vans, which traveled across the country showing movies with a projector, and local video centers—small venues for VHS cassette rentals, which also showed films for an audience of a dozen or more, with plastic chairs set up in the evenings and a small TV propped up in a corner. Screening times were typically 12:30 PM, 4 PM, and 6:30 PM. Allen Gyimah, considered to be the first person in the country to make a feature on VHS tape (as opposed to film) and screen it, started by filming weddings and funerals with a camera acquired from the UK.

In its brief flowering from 1985 to the late nineties, the “Golden Age” celebrated in this exhibition was a kind of film-poster version of the Italian Renaissance, with competing artists—none of whom had formal training—and their different studios and schools flourishing with support from patrons across Accra, Kumasi, and central Ghana. Video distributors would commission painters to make fifty or more of each poster, which they then rented out to screening centers.

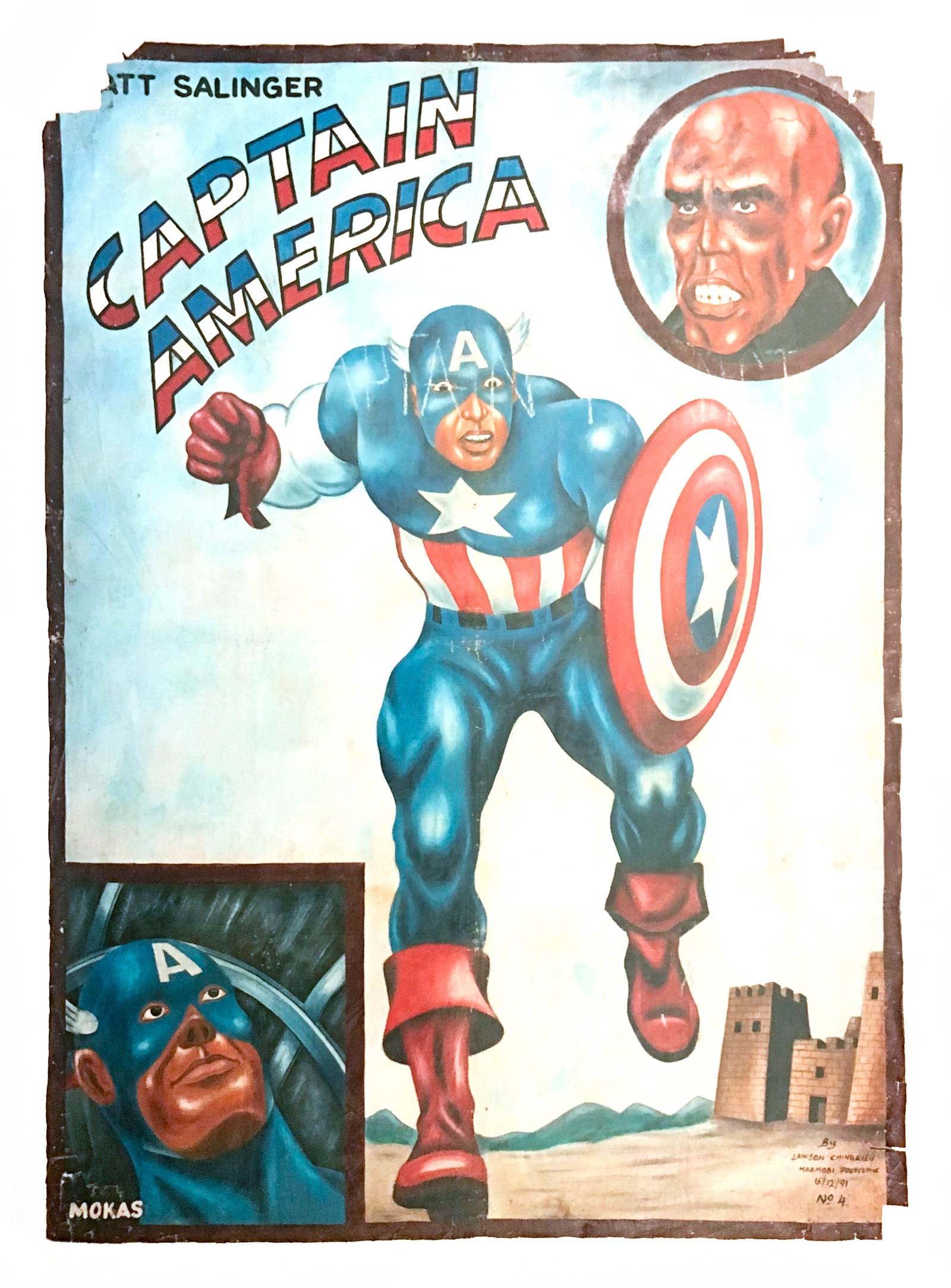

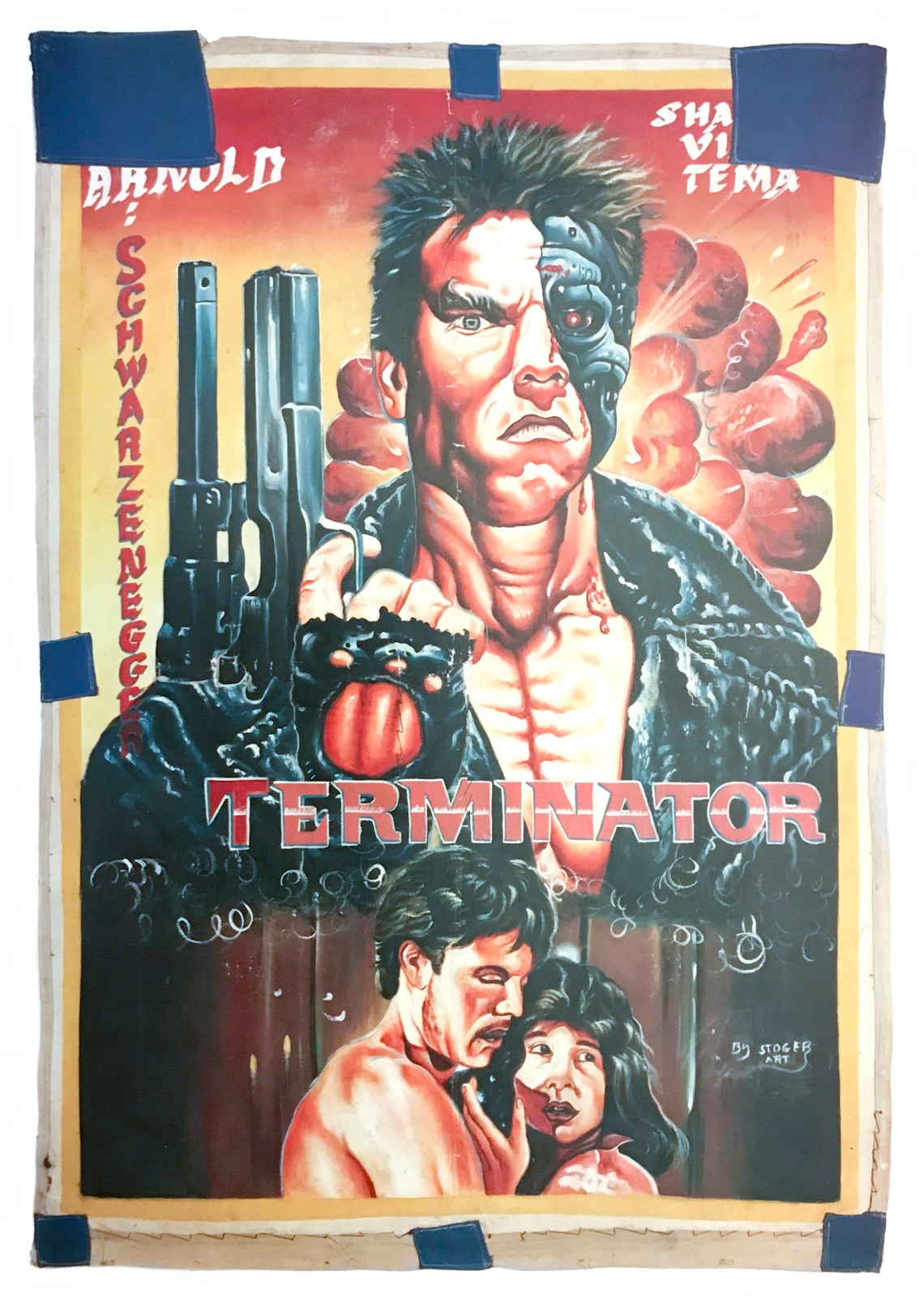

Individual artists, who often took noms de plume with the street style of graffiti artists, gained recognition in the business: Leonardo was known best for his depictions of gore and fire; Heavy J for his signature colored borders; and Death is Wonder, whose “unique approach to spatial orientation and highly gestural brush strokes” the exhibition highlights in the accompanying brochure. The aforementioned Jasper, at the age of thirteen, completed an apprenticeship with the Accra-based painter Emmanuel Okai, and worked briefly for a textile company, Spintix, before deciding to focus solely on his painting in 1986. He was also a bodybuilder—or a “beefcake,” as the ripped young men in Western movies and magazines were called—and pioneered the much imitated “muscles on muscles” aesthetic that made the poster for The Barbarians locally famous, whereby rolls and rolls of improbable brawn cover every skin surface.

Jasper would go on to have apprentices himself, such as Heavy J and Stoger. At the Poster House, you can see Jasper’s influence in Stoger’s 1990 painting of Terminator, wherein Arnold Schwarzenegger’s well-defined chest pokes out of black leather jacket as he holds up a gun. Behind him are explosions masterfully rendered in the blend of reds and oranges that define Stoger’s work.

Amid the “Golden Age,” Gyimah made the movie Abyssinia (1987)—a ghost story screened only at Gyimah’s video centers, and therefore seen by very few people—with actors from the local theater industry. Not too long thereafter, the arrival of cheap photo-offset printing technologies, encouraged by the fast rising Nollywood and Ghallywood English and local-language film industries, soon obviated hand-painted posters. I didn’t know it then, but the end of the 1990s, when I abandoned my apprenticeship at the video center, in fact coincided with the twilight of an artistic epoch in Ghana.

Western consumers, critics, and curators have tended to regard the paintings made during this period as amateurish, wacky, or grotesque attempts by infantile artists to reproduce the original VHS covers. But this simplifies not only the process by which the posters were made, but also the long and complex history their artists drew upon. “The roots of the craft goes back to the early 1900s with the concert party tradition that toured around the countryside,” media anthropologist Joseph Oduro-Frimpong told me. At colonial schools, African students would put on shows for their administrators during “Empire Day,” in celebration of Queen Victoria and the British Empire.

Soon, people began touring the country performing these sketches, comic and dramatic dialogues, and other theatrical forms they had learned, using local languages and replacing the British stock characters with ones from folklore, such as Ananse the trickster. “The concert party producers would hire a roadside artist, tell them what the concert was about, and the artist would often go home and execute sketches on boards.” These plays frequently included exaggerated characters and paranormal or supernatural beings, so their advertising billboards demanded a strong imagination and animated colors.

Advertisement

The concert parties continued throughout the twentieth century, and a trickle of Hollywood, Bollywood, and other Asian movies would provide entertainment until another coup in 1979 ordered an early curfew that Oduro-Frimpong told me, “killed nightlife completely, leading to a mass exodus of musicians and performers.” Social life migrated indoors, and with the arrival of the VHS, individuals with connections abroad could run and stock the video screening centers or video libraries like the one where I briefly worked. “Film became the social event from the era of concert parties,” Oduro-Frimpong said.

In the last couple years, there has been a renewed interest in the movie-poster paintings and a tourist market has developed around them. Collectors around the world now commission a variety of works, and individuals in Ghana can visit the artists’ shops for a more boutique experience like a very different Conan did recently on his trip to Accra. This has occurred amid the larger revival of the popular arts in Ghana, two decades on from the dark days of curfews and dictatorships that put constraints on movement and the creative mind. Contemporary art festivals like Chale Wote, showcasing public art like graffiti murals and street painting, build on the spirit of curiosity, improvisation, and cultural exchange pioneered by the groundbreaking painters of Ghana’s movie poster “Golden Age.”

“Baptized By Beefcake: The Golden Age of Hand-Painted Movie Posters from Ghana” is on view at New York City’s Poster House through February 16.